Continuing Education Activity

Nummular dermatitis is a pruritic inflammatory dermatosis predominantly observed in middle-aged adults. Although many potential triggers have been identified, the etiology of this condition is not fully understood. Despite its typically benign course, nummular dermatitis can negatively impact patients' quality of life commensurate with the severity of the condition. This activity describes the evaluation and treatment of nummular dermatitis and explains the healthcare team's role in managing patients with this condition.

Recognized as discoid eczema or nummular eczema, nummular dermatitis manifests as pruritic, coin-shaped lesions, commonly affecting the extremities and occasionally the trunk. This chronic inflammatory skin disorder is considered a distinctive manifestation within endogenous or idiopathic eczema categories, with certain experts proposing its reclassification as a subtype of atopic dermatitis. Encouragingly, the prognosis for nummular dermatitis is typically favorable. Effective management predominantly involves conservative measures and the application of topical corticosteroids, resulting in substantial remission for most patients.

Objectives:

Identify potential triggers of nummular dermatitis.

Identify the distribution and morphologic patterns of nummular dermatitis.

Determine potential adjunctive tests and management options available for nummular dermatitis.

Apply effective interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination to improve outcomes for patients with nummular dermatitis.

Introduction

Nummular dermatitis, also called discoid eczema or nummular eczema, is a pruritic eczematous dermatosis characterized by multiple coin-shaped lesions. This chronic inflammatory skin disease commonly involves the extremities and, less commonly, the trunk. Nummular dermatitis is regarded as a distinctive form of endogenous or idiopathic eczema, although some experts suggest it should be classified as a subtype of atopic dermatitis. The prognosis of this condition is excellent. Most cases can be treated successfully with conservative measures and topical corticosteroids, and most patients will eventually achieve remission.[1][2]

Etiology

The exact etiology of nummular dermatitis is unknown. Numerous factors have been implicated, such as xerosis, contact allergy to metals, decreased cutaneous lipid production, reactivity to environmental aeroallergens, staphylococcal colonization, use of irritating and drying soaps, frequent bathing with hot water, environments with low humidity, skin trauma (Koebner phenomenon), exposure to rough fabrics such as wool, breast implantation, and certain medications (antivirals, interferon, isotretinoin, retinoids, guselkumab, ribavirin, and gold compounds).[3][4][5][6][7][8] Chronic venous stasis may predispose individuals to the development of nummular dermatitis in the lower extremities.[4]

Epidemiology

Nummular dermatitis has a bimodal distribution, predominantly affecting females aged 15 to 25 years and males aged 50 to 65 years. Prevalence ranges from 0.1% to 9.1%.[3]

Pathophysiology

The natural aging process, chronic venous stasis, bacterial colonization, certain drugs, and sensitization to contact allergens, most commonly metals (nickel sulfate, potassium dichromate, cobalt chloride), may compromise the cutaneous lipid barrier.[3] The release of cytokines (ie, interferon-gamma [IFN-g] and interleukin [IL]-17) results in increased recruitment of T-cells, dendritic cells, and Langerhans' cells, eventually leading to epidermal hyperplasia and the development of characteristic lesions.[9] A report of nummular dermatitis after treatment of a refractory palmoplantar psoriasis patient with the interleukin IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab, suggests that the balance of T-helper cell type 1 (Th1) and T-helper cell type 2 (Th2) cytokines may play a role in the pathogenesis.[8]

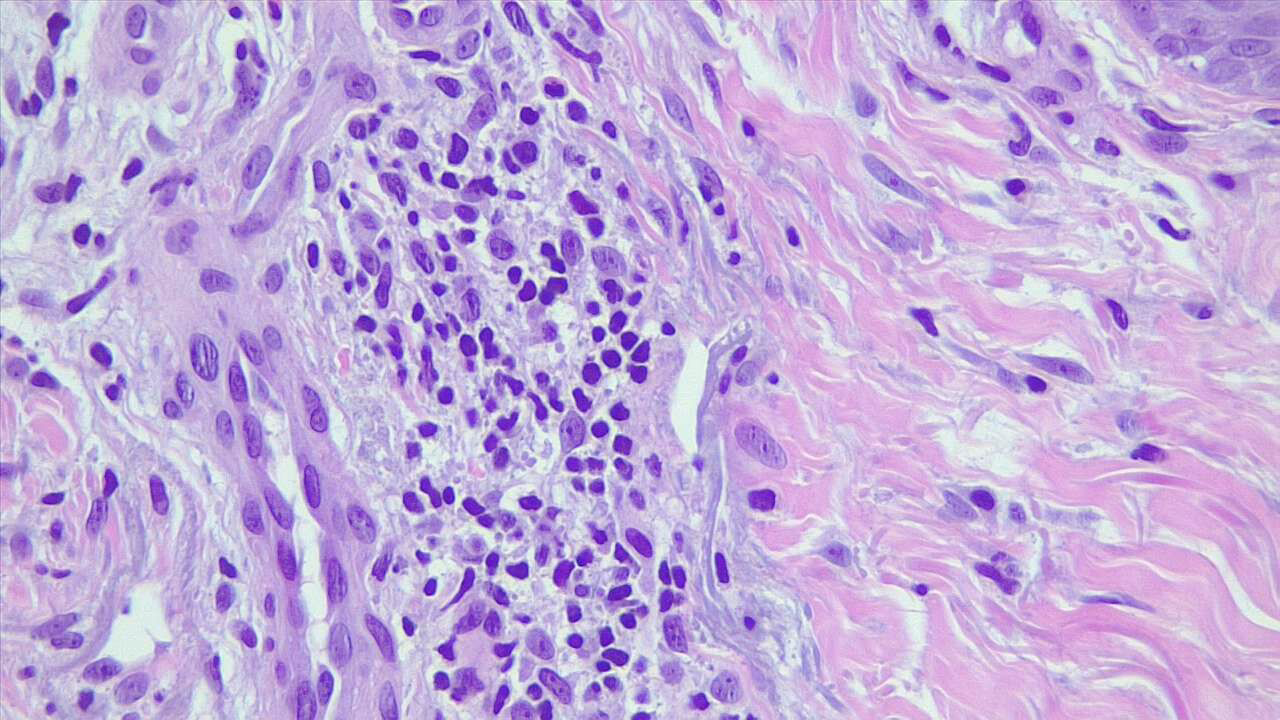

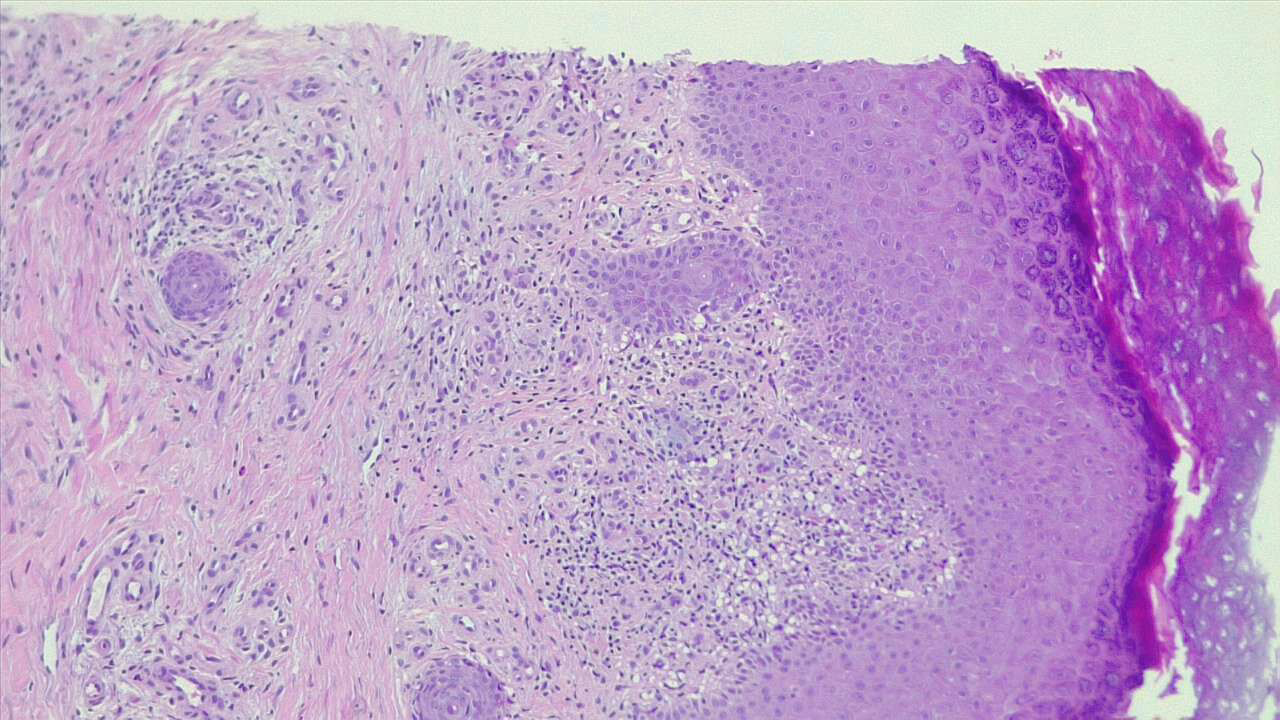

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings of nummular dermatitis are not specific; instead, they share features of spongiotic dermatitis (the histopathological indicator of eczematous dermatitis) that may be subacute or chronic. Features that may be present include spongiosis, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates with some eosinophils and occasional neutrophils and plasma cells, vascular dilatation, and mild papillary edema.

History and Physical

Acutely, lesions may begin as papules or vesicles that coalesce into plaques. When established, lesions will appear symmetrically distributed, sharply defined, round or coin-shaped, and erythematous; eczematous plaques will range in size from 1 to 10 cm. Late-stage lesions may develop a drier scale and lichenification. Lesions may be associated with mild to intense pruritus. Lesion and symptom severity are exacerbated by behaviors that decrease the skin's natural moisture barrier, such as harsh soaps and long, hot, frequent showering. The lower extremities are most commonly involved, followed by the upper extremities and trunk. The face and scalp are spared. Postinflammatory pigmentary changes typically persist after resolution. Dermoscopic findings may reveal scales, shiny yellow clods, and irregularly distributed brownish-red globules.[10]

Evaluation

Nummular dermatitis is a clinical diagnosis based on its classical presentation of pruritic coin-shaped erythematous and eczematous plaques symmetrically distributed in a person with diffusely dry skin. A dermoscopic evaluation may assist with the diagnosis; other laboratory tests are not generally necessary.[11] Ancillary tests to help distinguish it from other causes of annular erythematous plaques, if indicated, include potassium hydroxide wet-mount examination of skin scrapings, skin bacterial culture, biopsy, and patch testing. A skin swab for bacterial culture may be performed in patients with crusted or exudative lesions. Patch testing may be helpful in patients with recalcitrant disease and having a history suggestive of allergic contact dermatitis.[12][13]

Treatment / Management

The management of nummular dermatitis focuses on restoring the natural skin barrier and avoiding behaviors that dry and irritate the skin.[14]

General Measures

Frequent moisturization with thick emollients such as petroleum jelly is recommended. Moisturizers containing ceramides have been proven effective in reducing transepidermal water loss.[15] Patients should be instructed to take short (≤5 minutes) lukewarm showers, use gentle hydrating soaps, and apply emollients immediately after showering while the skin is still slightly wet. They should also be encouraged to avoid tight clothing and irritating fabrics and use a humidifier.

Topical Therapies

High- or ultrahigh potency (classes I-III) topical corticosteroids applied directly to affected skin 1 to 2 times daily help decrease inflammation and pruritus. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) may be used as steroid-sparing topical agents. A typical alternating schedule includes topical corticosteroids on weekdays and topical calcineurin inhibitors on weekends. For isolated recalcitrant lesions, intralesional triamcinolone may be a treatment option (0.5-1 mL of 4-5 mg/mL triamcinolone per lesion).

Phototherapy

For widespread disease in which topical treatment may not be feasible, narrowband UVB light therapy should be considered. Light therapy should be administered 2 to 3 times weekly, slowly titrating to the appropriate duration and desired clinical response. The therapy should be discontinued if a response is not noted after 30 treatments. In patients who respond, the frequency should be reduced to once weekly for a month, then to every other week for 2 months, as needed and tolerated. For all patients undergoing phototherapy, the potential increased risk of skin cancer should be weighed against the benefits of avoiding the use of systemic immunosuppressants in the individual patient.

Systemic Therapies

If light therapy is not available, systemic immunosuppressants and immunomodulators have been used to treat extensive recalcitrant disease, including:

- Systemic corticosteroids: Oral prednisone can be initiated at 40 mg per day, with the dose reduced by 10 mg every 5 days before being discontinued. Alternatively, intramuscular triamcinolone at a dose of 40 mg can be given up to once every 3 months.

- Methotrexate: A dose of 10 to 15 mg per week is an alternative therapy for patients for whom systemic corticosteroids are contraindicated or for whom the disease recurs shortly after corticosteroid discontinuation.[16]

- Cyclosporine: A dose of 3 to 5 mg/kg per day is an additional alternative to systemic corticosteroids.

- Dupilumab: This IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor, approved for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, has been reported as effective in several small series of patients with nummular eczema.[17][18]

If signs of a secondary bacterial infection or a bacterial swab of lesional skin are positive, treatment with topical or oral antistaphylococcal antibiotics is recommended, depending on whether lesions are localized or diffuse. Sensitivities and local antibiotic resistance patterns may impact the choice of antibiotic. Sedating antihistamines such as hydroxyzine or diphenhydramine may be used to provide relief for severe pruritus, especially at nighttime.

Differential Diagnosis

There are several differential diagnoses for nummular eczema.

Atopic dermatitis: Distinguishing idiopathic nummular eczema from atopic dermatitis with primarily nummular lesions requires the application of validated diagnostic criteria.

Allergic contact dermatitis: This condition may present with nummular lesions. Patch testing can help identify the causative allergen.

Plaque psoriasis: This condition classically presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silvery scale plaques involving the scalp, elbows, and knees, although any site may be affected.

Stasis dermatitis: This condition is often associated with findings of venous insufficiency, including edema, varicose veins, and atrophic hypopigmented scars (atrophie blanche). Lesions consist of erythematous patches that may progress to scaly plaques involving the ankle and distal lower leg. Plaques may be exudative, lichenified, or superimposed on varicosities.

Asteatotic eczema: Also known as eczema craquelé, this condition appears as diffuse erythema and fine-scale, with small irregular fissures and cracks, most commonly on the bilateral lower legs.

Lichen aureus: This condition demonstrates small petechiae and well-defined red to brown macules or plaques symmetrically on the bilateral lower legs or rarely on the trunk and upper extremities.

Fixed drug eruption: This condition presents with 1 or multiple well-circumscribed circular red to brown patches or edematous plaques that recur in the exact location when the patient is exposed to the implicated drug.

Erythema annulare centrifugum: This condition appears as arcuate or round plaques with central clearing with a trailing scale at the outermost edge.

Bullous pemphigoid: This condition can present with nonspecific, pruritic, eczematous lesions for a prolonged period before the appearance of classic blisters.

Tinea corporis: This condition presents with one or multiple circular erythematous scaly plaques with central clearing. A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation will show the segmented hyphae and arthrospores characteristic of all dermatophyte infections.

Majocchi granuloma: This condition demonstrates multiple perifollicular pustules coalescing to form erythematous scaly plaques.

Impetigo: This condition presents as "honey-colored" or golden-crusted papules and plaques with an erythematous base.

Secondary syphilis: This condition appears as diffuse pink, red, violaceous, or brown papules and plaques with an overlying scale that often involves the palms and soles.

Pityriasis rosea: This condition presents with pale pink circular or oval patches or thin plaques with a collarette of fine white scale.

Patch or plaque stage mycosis fungoides: Also known as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, this condition presents as erythematous to slightly hyperpigmented patches or thin plaques with overlying fine scale. Lesions may measure 2 to 20 cm and occur primarily in areas of the body protected from sun exposure (ie, the buttocks or axillary folds).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ: Also known as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, this condition usually presents as a singular (rarely multiple) erythematous, scaly, well-defined, thin plaque with a circular or irregular shape.

Prognosis

Nummular dermatitis often follows a chronic course characterized by relapses and remissions over months to years.

Complications

Because of the impaired skin barrier, lesional skin may become secondarily infected; staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly implicated pathogen. Impetiginized lesions can display purulent ooze and thicker golden crusting than noninfected lesions. A bacterial swab should be performed for culture and sensitivities. Based on local antimicrobial resistance patterns, doxycycline or another antistaphylococcal antibiotic may be selected initially; further treatment can be tailored according to the resultant sensitivities. As with any inflammatory condition of the skin, there may be postinflammatory dyspigmentation of the skin, including erythema, hypo-, or hyperpigmentation.

Consultations

Most nummular dermatitis cases should respond to conservative measures such as gentle skincare and bland emollients used in combination with mid- to high-potency steroids. Consultation with a dermatologist should be considered in refractory, widespread, or atypical cases. Further evaluation may include skin scraping with potassium hydroxide preparation, bacterial swab for culture and sensitivities, biopsy, or patch testing, as discussed previously. If narrow-band UVB light therapy, systemic immunosuppressant, or immunomodulator is warranted, this should also be carried out under a dermatologist's supervision.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be counseled that behavior modification can significantly improve nummular dermatitis. Patients should be instructed to take short (≤5 minutes) lukewarm showers, use gentle hydrating liquid cleansers, and apply emollients immediately after showering while the skin is still damp. A bland ointment, such as petroleum jelly, is recommended. Encourage patients to avoid tight clothing and irritating fabrics such as wool. Otherwise, patients must be instructed to follow their prescription regimen as directed.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Inflammatory dermatoses such as nummular dermatitis are often treated by primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or dermatologists. Although the differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is quite broad, it is most often clinically diagnosed by recognizing its morphology, distribution, and epidemiology patterns. Ancillary testing such as skin scraping with potassium hydroxide preparation, bacterial swab for culture and sensitivities, or biopsy may be performed in the primary care or dermatologic setting. If the nummular dermatitis is unresponsive to conservative management and topical corticosteroids, it is appropriate to consult a dermatologist. A specialist should supervise patch testing, narrowband UVB treatment, systemic immunosuppressant, or immunomodulatory therapy.

Treatment of nummular dermatitis can be optimized with an interprofessional team approach. The patient’s nurse, primary care provider, or dermatologist should monitor for therapy compliance, report any adverse effects, and relay the response to therapy to the remainder of the team. This interprofessional teamwork will enhance patient outcomes and minimize adverse reactions in caring for patients with nummular dermatitis.