[1]

Chen EY, Vaccaro GM. Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2018 Sep:31(5):267-277. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1660482. Epub 2018 Sep 4

[PubMed PMID: 30186048]

[2]

Hsieh YH, Leung FW. Increase your adenoma detection rate without using fancy adjunct tools. Tzu chi medical journal. 2018 Jul-Sep:30(3):127-134. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_86_18. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30069119]

[3]

Turner JS, Henry D, Chase A, Kpodzo D, Flood MC, Clark CE. Adenoma Detection Rate in Colonoscopy: Does the Participation of a Resident Matter? The American surgeon. 2018 Jun 1:84(6):1064-1068

[PubMed PMID: 29981650]

[4]

Yoshizawa N, Yamaguchi H, Kaminishi M. Differential diagnosis of solitary gastric Peutz-Jeghers-type polyp with stomach cancer: a case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2018:51():261-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.09.005. Epub 2018 Sep 10

[PubMed PMID: 30219660]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[5]

Click B, Pinsky PF, Hickey T, Doroudi M, Schoen RE. Association of Colonoscopy Adenoma Findings With Long-term Colorectal Cancer Incidence. JAMA. 2018 May 15:319(19):2021-2031. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5809. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29800214]

[6]

Mouchli MA, Ouk L, Scheitel MR, Chaudhry AP, Felmlee-Devine D, Grill DE, Rashtak S, Wang P, Wang J, Chaudhry R, Smyrk TC, Oberg AL, Druliner BR, Boardman LA. Colonoscopy surveillance for high risk polyps does not always prevent colorectal cancer. World journal of gastroenterology. 2018 Feb 28:24(8):905-916. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i8.905. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29491684]

[7]

Dabbous HK, Mohamed YAE, El-Folly RF, El-Talkawy MD, Seddik HE, Johar D, Sarhan MA. Evaluation of Fecal M2PK as a Diagnostic Marker in Colorectal Cancer. Journal of gastrointestinal cancer. 2019 Sep:50(3):442-450. doi: 10.1007/s12029-018-0088-1. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29626277]

[8]

Raab M, Sanhaji M, Matthess Y, Hörlin A, Lorenz I, Dötsch C, Habbe N, Waidmann O, Kurunci-Csacsko E, Firestein R, Becker S, Strebhardt K. PLK1 has tumor-suppressive potential in APC-truncated colon cancer cells. Nature communications. 2018 Mar 16:9(1):1106. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03494-4. Epub 2018 Mar 16

[PubMed PMID: 29549256]

[9]

Castro J, Cuatrecasas M, Balaguer F, Ricart E, Pellisé M. Serrated polyposis syndrome associated with long-standing inflammatory bowel disease. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas. 2017 Nov:109(11):796-798. doi: 10.17235/reed.2017.5068/2017. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29027468]

[10]

Hakimian S, Jawaid S, Guilarte-Walker Y, Mathew J, Cave D. Video capsule endoscopy as a tool for evaluation of obscure overt gastrointestinal bleeding in the intensive care unit. Endoscopy international open. 2018 Aug:6(8):E989-E993. doi: 10.1055/a-0590-3940. Epub 2018 Aug 3

[PubMed PMID: 30083589]

[11]

Iwai T, Imai K, Hotta K, Ito S, Yamaguchi Y, Kawata N, Tanaka M, Kakushima N, Takizawa K, Ishiwatari H, Matsubayashi H, Ono H. Endoscopic prediction of advanced histology in diminutive and small colorectal polyps. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2019 Feb:34(2):397-403. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14409. Epub 2018 Aug 16

[PubMed PMID: 30070395]

[12]

Aihara H, Kumar N, Thompson CC. A Web-Based Education Program for Colorectal Lesion Diagnosis with Narrow Band Imaging Classification. Digestion. 2018:98(1):11-18. doi: 10.1159/000486481. Epub 2018 Apr 19

[PubMed PMID: 29672309]

[13]

Jover R, Dekker E, Schoen RE, Hassan C, Pellise M, Ladabaum U, WEO Expert Working Group of Surveillance after colonic neoplasm. Colonoscopy quality requisites for selecting surveillance intervals: A World Endoscopy Organization Delphi Recommendation. Digestive endoscopy : official journal of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. 2018 Nov:30(6):750-759. doi: 10.1111/den.13229. Epub 2018 Jul 26

[PubMed PMID: 29971834]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[14]

Kang H, Thoufeeq MH. Size of colorectal polyps determines time taken to remove them endoscopically. Endoscopy international open. 2018 May:6(5):E610-E615. doi: 10.1055/a-0587-4681. Epub 2018 May 8

[PubMed PMID: 29756019]

[15]

Gibson DJ, Nolan B, Rea J, Buckley M, Horgan G, Sheahan K, Doherty GA, O'Donoghue D, Mulcahy HE, Smith A, Cullen G. A prospective study of faecal immunochemical testing following polypectomy in a colorectal cancer screening population. Frontline gastroenterology. 2018 Oct:9(4):295-299. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2017-100869. Epub 2017 Nov 4

[PubMed PMID: 30245792]

[16]

Arana-Arri E, Imaz-Ayo N, Fernández MJ, Idigoras I, Bilbao I, Bujanda L, Bao F, Ojembarrena E, Gil I, Gutiérrez-Ibarluzea I, Portillo I. Screening colonoscopy and risk of adverse events among individuals undergoing fecal immunochemical testing in a population-based program: A nested case-control study. United European gastroenterology journal. 2018 Jun:6(5):755-764. doi: 10.1177/2050640618756105. Epub 2018 Jan 24

[PubMed PMID: 30083338]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[17]

Kawamura T, Sakai H, Ogawa T, Sakiyama N, Ueda Y, Shirakawa A, Okada Y, Sanada K, Nakase K, Mandai K, Suzuki A, Morita A, Tanaka K, Uno K, Yasuda K. Feasibility of Underwater Endoscopic Mucosal Resection for Colorectal Lesions: A Single Center Study in Japan. Gastroenterology research. 2018 Aug:11(4):274-279. doi: 10.14740/gr1021w. Epub 2018 Feb 8

[PubMed PMID: 30116426]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[18]

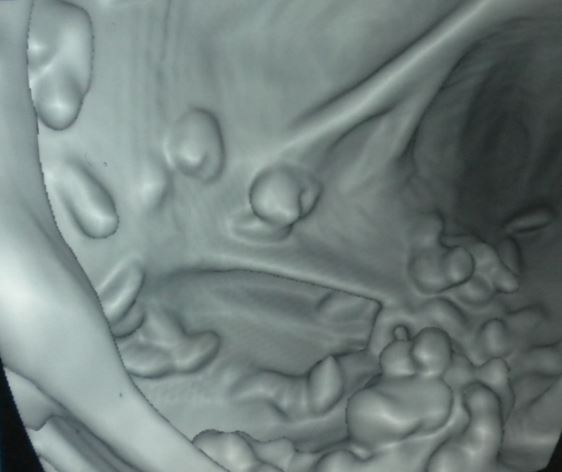

Obaro AE, Burling DN, Plumb AA. Colon cancer screening with CT colonography: logistics, cost-effectiveness, efficiency and progress. The British journal of radiology. 2018 Oct:91(1090):20180307. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180307. Epub 2018 Jul 5

[PubMed PMID: 29927637]