Introduction

The vestibulocochlear nerve consists of the vestibular and cochlear nerves, also known as cranial nerve eight (CN VIII). Each nerve has distinct nuclei within the brainstem. The vestibular nerve is primarily responsible for maintaining body balance and eye movements, while the cochlear nerve is responsible for hearing.[1]

CN VIII injuries result from pathological processes or injuries that commonly involve the cerebellopontine angle (CPA), the internal auditory canal (IAC), or the inner ear. In such cases, symptoms such as vertigo, nystagmus, tinnitus, and sensorineural hearing loss may occur.[2][3]

Structure and Function

The Cochlear Nerve and Auditory System

The cochlear nerve is responsible for transmitting auditory signals from the inner ear to the cochlear nuclei within the brainstem and ultimately to the primary auditory cortex within the temporal lobe.[3][4]

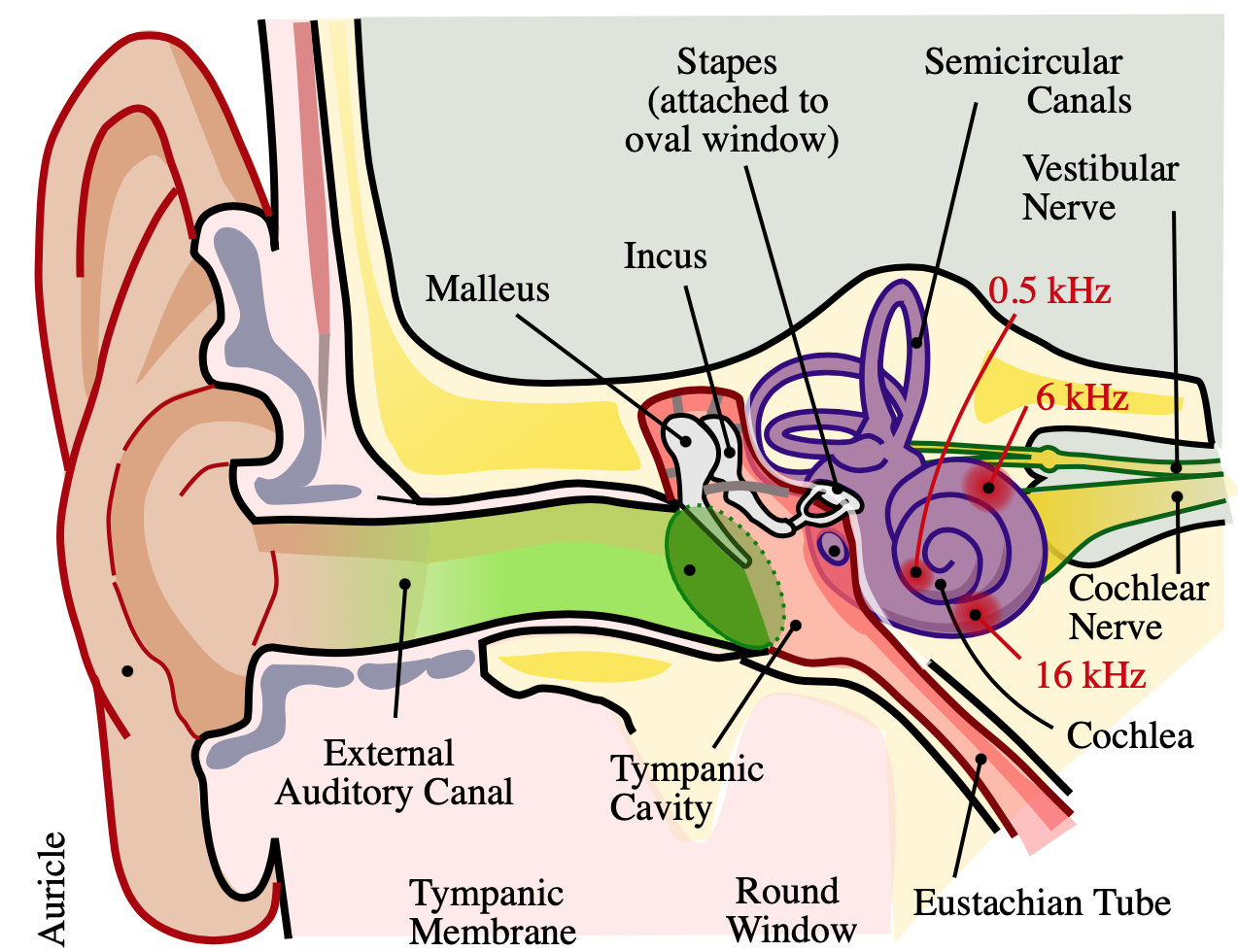

The cochlea is a spiral, fluid-filled cavity in the bony auditory labyrinth that contains the organ of Corti along its basilar membrane. The bipolar neurons making up the spiral (cochlear) ganglion create the link between the central nervous system (CNS) and the organ of Corti. The spiral ganglion is located at the spiral canal of the modiolus. Type I and Type II neurons populate the spiral ganglion, and both send peripheral processes to the ciliated hair cells of the organ of Corti and central processes that join together to form the cochlear nerve. Type 1 neurons are comparatively larger, myelinated, and account for 90% of cochlear nerve cells. Type 2 neurons are smaller and nonmyelinated. Type I neurons project to the inner hair cells of the organ of Corti, while Type II neurons project to the outer hair cells.[1][5][6][7]

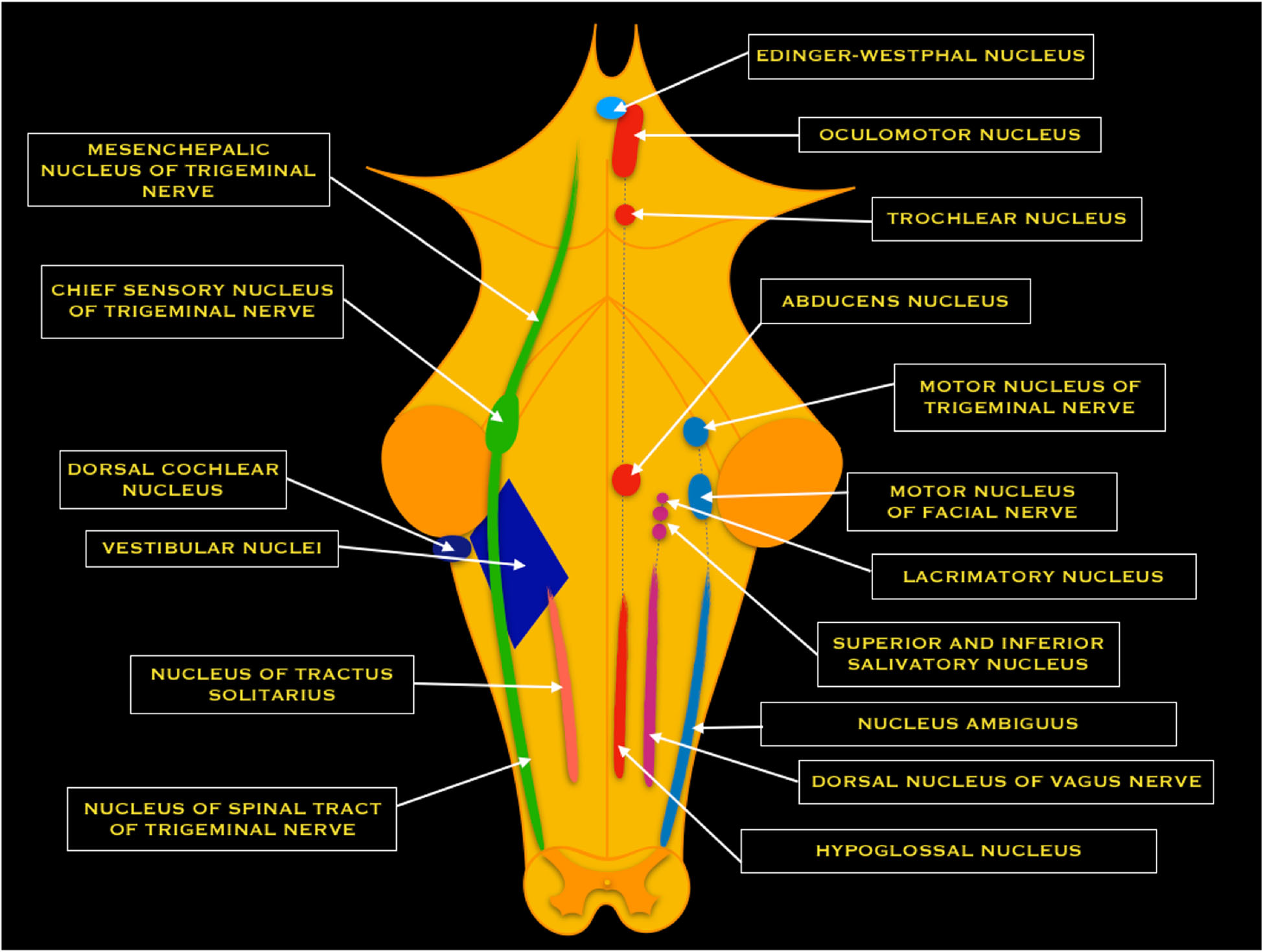

Central projections from the spiral ganglion form the cochlear nerve before entering the IAC. Within the IAC, the cochlear nerve joins the vestibular nerve to form CN VIII. The nerve fibers run past the CPA and enter the brainstem at the pontomedullary junction to innervate the cochlear nuclei within the rostral pole of the upper medulla. There are three divisions of the cochlear nuclei: anteroventral (AVCN), dorsal (DCN), and posteroventral (PVCN).[1][4][5]

Upon entering the brainstem, the cochlear nerve separates from the vestibular nerve and branches into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior division innervates the AVCN, while the posterior division innervates the DCN and PVCN. Cochlear nerve fibers are characterized tonotopically. Afferent nerve fibers from hair cells at the base of the cochlea transmit high frequencies. The afferents from the apex of the cochlea transmit low frequencies. This organization is preserved within the cochlear nuclei.[5]

After the cochlear nuclei, the fibers cross and join the contralateral lateral lemniscus toward the midbrain inferior colliculus. Next, the fibers reach the thalamic medial geniculate nucleus before traveling to the primary auditory cortex, within the temporal lobe.[3][4]

The Vestibular Nerve and Vestibular System

The vestibular nerve relays information related to motion and position. The vestibular system involves coordinated communication between the vestibular apparatus (semicircular canals, saccule, utricle), ocular muscles, postural muscles, brainstem, and cerebral cortex.[3][8]

The peripheral vestibular apparatus is located within the temporal bone, and it consists of a bony and membranous labyrinth. The membranous labyrinth contains the sensory neuroepithelium and is located within the bony labyrinth, suspended in perilymph. The vestibular apparatus has five components: the utricle, saccule, and three semicircular ducts (contained within the semicircular canals). The two types of neuroepithelium are the macula and crista ampullaris, which both contain sensory hair cells. The utricle and saccule contain macula, while the semicircular canals contain crista ampullaris.[8]

The utricle and saccule sense the positioning of the head in space. Hair cells within the utricle respond to horizontal acceleration, while the hair cells within the saccule respond to vertical acceleration. The hair cells within the three semicircular ducts (lateral, superior, and posterior) respond to angular acceleration or head rotation.[8]

The stimulation of the hair cells results in depolarization and increased calcium (Ca) influx, leading to increased firing of afferent vestibular nerve fibers. Those fibers travel to the vestibular ganglion (Scarpa’s ganglion), located in the IAC. The ganglion is composed of bipolar neurons that send peripheral processes to the vestibular apparatus and central processes that join together to form the vestibular nerve. The ganglion is separated into superior and inferior divisions. The superior division receives input from the utricle and superior and lateral semicircular ducts. The inferior division receives input from the saccule and posterior semicircular duct.[8]

The superior and inferior post-ganglionic extensions join to form the vestibular nerve, which joins the cochlear nerve to become the CN VIII within the IAC. CN VIII runs past the CPA and enters the brainstem at the pontomedullary junction. The vestibular nerve separates from the cochlear nerve before reaching the vestibular nuclear complex. The vestibular nuclear complex consists of four nuclei: medial, lateral, superior, and inferior. These nuclei range from the caudal pons to the rostral medulla in two columns and are closely related to the floor of the fourth ventricle[8]. The vestibular nuclear complex receives input from the ipsilateral cerebellum, as well as the vestibular nerve, and projects to various ipsilateral and contralateral structures.

The medial nucleus receives input from the lateral semicircular ducts. It sends ascending fibers to the motor nuclei of the extraocular muscles ipsilaterally and contralateral via the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF), which helps facilitate the vestibulo-ocular reflex. The medial nucleus also helps mediate the vestibulospinal reflex by controlling head and neck movements.[8]

The superior nucleus receives input from the superior and posterior semicircular ducts and mediates the vestibulo-ocular reflex.[8] Furthermore, it projects to chiefly the ventral posterior intermediate nucleus of bilateral thalami in an ascending projection thought to play a fundamental role in conscious spatial awareness[9], mediating onward thalamocortical circuits[10].

The lateral nucleus receives input from all components of the vestibular apparatus and the vestibulocerebellum. Descending projections become the lateral vestibular tract within the ipsilateral spinal cord. This tract helps mediate the vestibulospinal reflex and maintain posture and balance.[8]

The inferior nucleus receives input from the utricle and saccule and sends fibers to the other three vestibular nuclei and the cerebellum.[8]

It has also been suggested that the auditory stimuli interact with the vestibular system to influence postural control.[11] Additionally, the vestibular system helps control blood pressure by using sympathetic pathways and the baroreceptors on the carotid and the aortic arch.[12]

Specifics regarding vestibular cortical connections are not well understood, but studies have suggested that the vestibular cortical area is adjacent to the parietal or insular cortex.[8]

Embryology

Cranial sensory organs in vertebrates arise from cranial placodes, which are areas of thickening in the ectoderm. The vestibular and cochlear apparatuses develop from the otic placode, which forms by the third week of gestation. During the fourth week, the otic placode invaginates to form the otic vesicle. This otic vesicle first gives rise to the cochlear (Spiral) and vestibular (Scarpa) ganglia, and from there, peripheral and central projections of the auditory and vestibular pathways are formed.[13][14][15]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Within the IAC, CN VIII is closely associated with the labyrinthine artery (internal auditory artery), a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. The labyrinthine artery bifurcates into the anterior vestibular and common cochlear arteries.[16]

At the CPA, notable vasculature includes the superior cerebellar artery, anterior inferior cerebellar artery, and petrosal vein, which are crucial to identify during the resection of vestibular schwannomas.[17][18]

Nerves

From the superior vestibular nucleus, ascending fibers travel through the MLF to the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerve nuclei to innervate the extraocular muscles, generating the vestibulo-oculomotor reflex.[8]

From the medial vestibular nucleus, descending fibers give rise to the medial vestibulospinal fascicles, which descend and give rise to the cervical motoneurons to create the vestibular-spinal reflex. This reflex is responsible for the stability of the head during movements.[8]

From the lateral vestibular nucleus, the lateral vestibulospinal fasciculus arises within the ipsilateral spinal cord. These fibers are dedicated to the vestibulospinal reflex, coordinating muscle movements in the trunk and proximal extensors that allow postural correction in response to vestibular stimuli.[8]

Muscles

Vestibular fibers of CN VIII innervate the motoneurons of the extraocular muscles to mediate the vesiculo-ocular reflex via the MLF. Additionally, vestibular fibers innervate postural spinal muscles to mediate the vestibulospinal reflex via the lateral and medial vestibular spinal tracts.[8]

Physiologic Variants

There does not appear to be any physiological variation of CN VIII but rather a variety of genetic malformations leading to pathology.

Surgical Considerations

Treatment options for vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) include microsurgical resection, radiation therapy, and observation. Post-operative mortality rates have decreased dramatically over the last century. Therefore, preserving facial nerve function has become the primary goal of surgery while removing as much of the tumor as possible. The three standard surgical approaches are middle fossa, retrosigmoidal, and translabyrinthine. Pre-operative hearing level, tumor size, and tumor location determine which approach is used.[19][20]

The middle fossa approach is reserved for patients with functional hearing levels and < 1 cm of CPA involvement. The retrosigmoidal approach is used for patients with functional hearing levels, > 1 cm CPA involvement, and no extension into the lateral IAC. The translabyrinthine approach is used for patients with no functional hearing or tumors that are too large to preserve hearing. Surgeons must weigh the risks and benefits of completely removing the tumor and possible injury to the facial nerve, cochlear nerve, or brainstem.[19][20]

CSF leak is the most commonly reported complication of vestibular schwannoma surgery. There is no significant difference in the frequency of CSF leaks between the three approaches. Post-operative meningitis is another feared complication and can be either aseptic or bacterial. Aseptic meningitis is more common; it is due to an inflammatory reaction against foreign material, such as blood, hemoglobin, and bone dust, within the subarachnoid space. Common presenting symptoms of aseptic meningitis include neck stiffness, fever, headache, and fatigue with negative bacterial cultures. Both types of meningitis are associated with CSF leaks. Dural sinus thrombosis, seizures, and hemorrhages are less common complications. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to decrease the likelihood of these complications.[19]

Clinical Significance

CN VIII pathology can result from direct trauma, congenital malformations, tumor formation, infection, and vascular injury. Presenting symptoms include vertigo, nystagmus, tinnitus, and sensorineural hearing loss.

Auditory pathology can occur anywhere along the auditory pathway, central or peripheral. The most common mechanisms of injury are infarcts and demyelination (i.e., Multiple Sclerosis). Patients can present with unilateral or bilateral sensorineural loss, depending on the location of the injury. Additionally, traumatic injury to the temporal bone can present with unilateral sensorineural loss due to IAC or bony labyrinth fracture. There can also be a concussive injury to the labyrinth. Imaging studies for such injuries are typically negative unless an MRI shows an intralabyrinthine hemorrhage.[4]

Notable congenital malformations of CN VIII include aplasia or hypoplasia. These malformations are subdivided into three subtypes: 1, 2A, and 2B. Type 1 refers to an aplastic CN VIII with a normal labyrinth. Type 2A refers to an aplastic/hypoplastic cochlear branch with an accompanying labyrinth malformation. Type 2B, the most common subtype, refers to an aplastic/hypoplastic cochlear branch but with a normal labyrinth.[2]

Vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) are of Schwann cell origin, and they are the most common CPA tumors. All cranial nerves have a peripheral transition zone where glial myelination by oligodendrocytes gives way to peripheral myelination by Schwann cells.[21] It was previously believed that all vestibular schwannomas arise from this transition zone, which for the vestibulocochlear nerve lies between 9.28mm - 13.84 mm along its length after exiting the brainstem, in the medial third of the interior auditory canal (IAC).[22] However, detailed anatomical study has revealed that schwannomas may occur at this point, as well as more laterally within the IAC and from the labyrinthine portion of the nerve.[23]

Bilateral vestibular schwannomas are the hallmark sign of neurofibromatosis Type 2 (NF-2), an autosomal dominant genetic syndrome. The usual presentation is progressive, unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, and commonly associated symptoms are tinnitus and vertigo. Notably, facial nerve (CN VII) palsy rarely occurs with vestibular schwannomas because the facial nerve is resistant to chronic pressure. MRI is the diagnostic imaging of choice.[2][19]

Acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) is characterized by vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and gait disturbances with an acute onset (seconds to hours), which are associated with nystagmus and head-motion intolerance (days to weeks). Etiology can either be peripheral, most commonly vestibular neuritis, or central, such as brainstem or cerebellar stroke. Vestibular neuritis is usually viral in origin and self-limiting, while a central stroke can have permanent effects. Therefore, it is critical to distinguish between these two etiologies to ensure proper patient care. This can be done at the bedside using the “Head-Impulse—Nystagmus—Test-of-Skew” (HINTS) exam. The horizontal head-impulse test, which assesses the vestibulo-ocular reflex, would be normal with central etiologies and abnormal with peripheral etiologies. Nystagmus would be vertical and/or bidirectional with central etiologies and unidirectional with peripheral etiologies, regardless of gaze direction. Skew deviation would be present with central etiologies and absent with peripheral etiologies.[24]

Also, the involvement of the facial nerve due to its proximity should not be excluded during evaluation.

Other Issues

A recent study reported nerve VIII neuritis (with paresthesia and facial muscle weakness) as a consequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus; the presence of such clinical symptoms should be considered in a situation of viral infections. [25]