Continuing Education Activity

A cephalohematoma is an accumulation of blood under the scalp, specifically in the subperiosteal space. During the birthing process, shearing forces on the skull and scalp result in the separation of the periosteum from the underlying calvarium, resulting in the subsequent rupture of blood vessels. Cephalohematomas are typically benign and self-limiting, often resolving independently without intervention. However, close monitoring is essential to manage potential complications, such as anemia or jaundice, that might arise from the breakdown of the collected blood. This topic provides a comprehensive overview of cephalohematoma in newborns, focusing on its etiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Participants will gain insights into the pathophysiology of cephalohematoma, the associated risk factors, and the latest evidence-based approaches for monitoring and treating this condition. The course will also address potential complications, such as hyperbilirubinemia and anemia, and discuss strategies for preventing adverse outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of cephalohematoma.

Differentiate the clinical presentation of newborns with cephalohematoma.

Evaluate evidence-based monitoring and management strategies for infants with cephalohematoma.

Collaborate with an interprofessional team to develop and implement a comprehensive care plan that addresses the management of infants with cephalohematoma.

Introduction

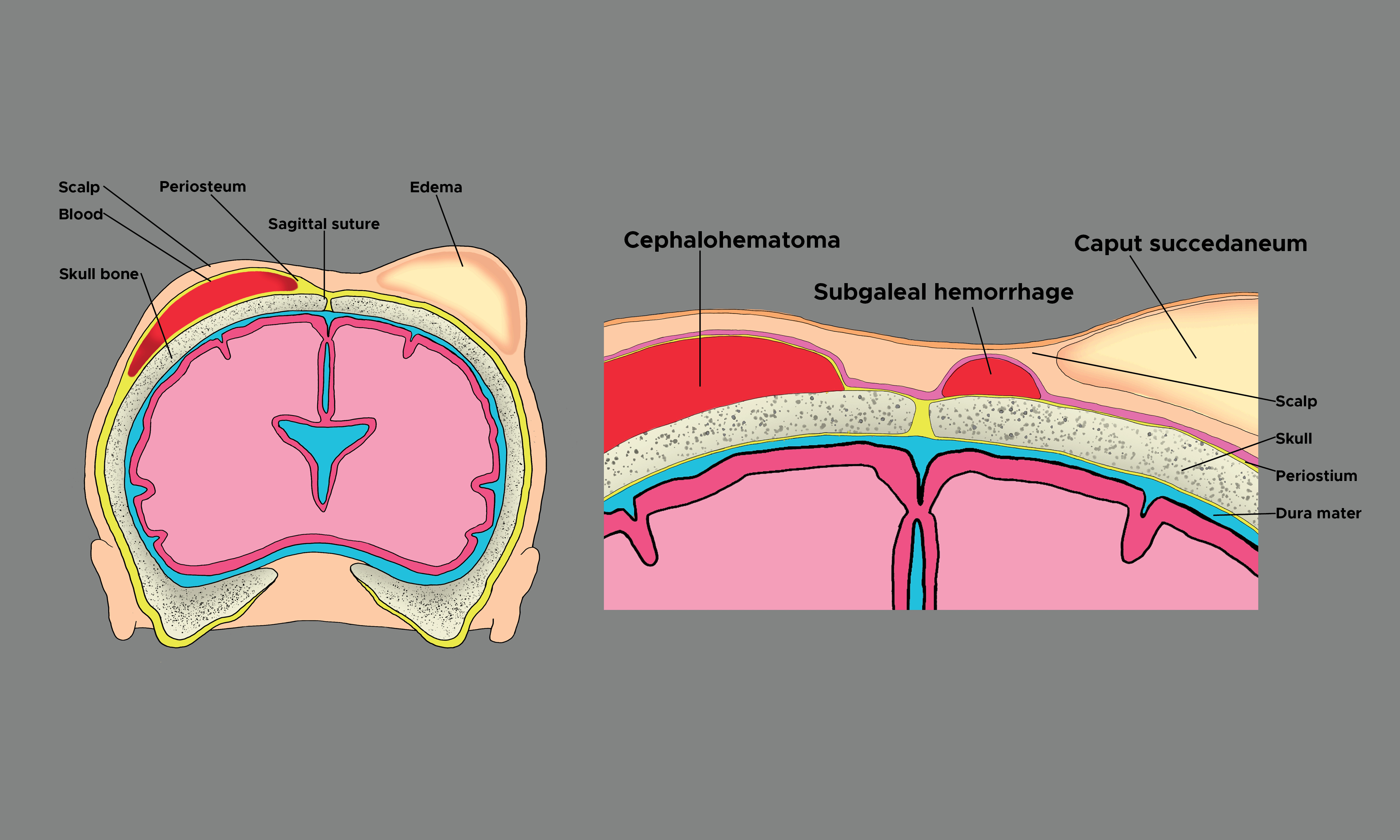

A cephalohematoma is an accumulation of subperiosteal blood, typically located in the occipital or parietal region of the calvarium (see Image. Cephalohematoma).[1][2][3] During the birthing process, shearing forces on the skull and scalp result in the separation of the periosteum from the underlying calvarium, resulting in the subsequent rupture of blood vessels.[2] The bleeding is gradual; therefore, a cephalohematoma is typically not immediately evident at birth.[4][5][6] A cephalohematoma instead develops during the following hours or days after birth, within the first 1 to 3 days of birth being the most common age of presentation.[1] Because the cephalohematoma is deep in the periosteum, the underlying calvarium defines the collections' boundaries. In short, a cephalohematoma is confined and does not cross the midline or calvarial suture lines.

Etiology

The etiology of cephalohematoma is the rupture of blood vessels crossing the periosteum due to the pressure on the fetal head during birth. During the birthing process, pressure on the skull from the rigid birth canal or using ancillary external forces such as forceps or a vacuum extractor can rupture these small and delicate blood vessels, resulting in the collection of sanguineous fluid.[7] Factors that increase pressure on the fetal head and ultimately increase the risk of the neonate developing a cephalohematoma include the following:

- A prolonged second stage of labor

- Macrosomia, or increased size of the infant relative to the birth canal

- Weak or ineffective uterine contractions

- Abnormal fetal presentation

- Instrument-assisted delivery with forceps or vacuum

- Multiple gestations

- Presentation of occiput in transverse or posterior position during delivery

- Cesarean section was initiated following the first stage of labor

- Coagulopathy [8]

These risk factors contribute to the traumatic impact of the birthing process on the fetal head. Aside from the birthing process, cephalohematoma may rarely occur in adults or juveniles following trauma or surgery.[2]

Epidemiology

Cephalohematoma occurs with an incidence of 0.4% to 2.5% of all live births.[3] For unknown reasons, cephalohematomas occur more often in male than female infants.[9][10] The lowest incidence of cephalohematoma occurs in unassisted vaginal delivery (1.67%).[11] Cephalohematomas are more common in primigravidae, large infants, infants in an occipital posterior or transverse occipital position at the start of labor, and following instrument-assisted deliveries with forceps or a vacuum extractor.[3] Amongst instrument-assisted deliveries, cephalohematomas occur most commonly following vacuum-assisted delivery (11.17% of deliveries), compared to forceps-assisted and cesarean delivery (6.35%).[12][11] A cesarean section that is initiated before the commencement of natural labor, however, is not associated with cephalohematoma.[3]

Pathophysiology

Cephalohematoma is a condition that most commonly occurs during the birthing process and rarely in juveniles and adults following trauma or surgery. External pressure on the fetal head results in the rupture of small blood vessels between the periosteum and calvarium. External pressure on the fetal head is increased when the head is compressed against the maternal pelvis during labor or when additional external forces are applied from instruments such as forceps or a vacuum that may be used to assist with the birth. Shearing action between the periosteum and the underlying calvarium causes slow bleeding. As blood accumulates, the periosteum elevates away from the skull. As the bleeding continues and fills the subperiosteal space, pressure builds, and the accumulated blood acts as a tamponade to stop further bleeding.

History and Physical

A comprehensive history of labor and birth is necessary to identify newborns at risk of developing cephalohematoma. Factors that increase pressure on the fetal head and the risk of developing a cephalhematoma should be identified, including a prolonged second stage of labor, abnormal fetal presentation, macrosomia, and operative or surgical delivery. Due to the slow nature of subperiosteal bleeding, cephalohematomas usually are absent at birth but become most noticeable within the first 1 to 3 days following birth. Therefore, repeated inspection and palpation of the newborn’s head is necessary to identify the presence of a cephalohematoma. Ongoing assessment to document the appearance of a cephalohematoma is important. Once a cephalohematoma is present, assessing and documenting changes in size is continued. Patients may initially present with a firm but increasingly fluctuant area of swelling over which the scalp moves easily.[2] A firm, enlarged unilateral or bilateral bulge on top of 1 or more bones below the scalp characterizes a cephalohematoma. The raised area cannot be transilluminated, and the overlying skin is usually not discolored or injured. Cranial sutures define the boundaries of the cephalohematoma. The parietal or occipital region of the calvarium is the most common site of injury, but a cephalohematoma can occur over any cranial bone.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of cephalohematoma is largely a clinical one. Diagnosis is based on the characteristic bulge on the newborn's head that does not cross cranial suture lines. The bulge may be initially firm and become more fluctuant as time passes. In contrast to caput succedaneum and subgaleal hematoma, cephalohematoma becomes most apparent in the first 1 to 3 days following birth rather than being immediately apparent.[13][14] Some providers may request additional tests, including skull X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans of the head, or head ultrasound for further evaluation.[15] Skull X-rays and CT imaging may be useful if there is suspicion of an underlying skull fracture. CT imaging and head ultrasound can be useful in evaluating intracranial hemorrhage and further defining the extracranial compartment in which the hemorrhage is located. Infants should be evaluated for bleeding diathesis, such as von Willebrand disease, which may have predisposed the infant to develop cephalohematoma.[2] Needle aspiration of the cephalohematoma is discouraged due to the risk of introducing infection and is only indicated if an infection is suspected. Escherichia coli is the primary pathogen associated with an infected cephalohematoma.[2][1][16]

Treatment / Management

Treatment and management of cephalohematoma are primarily observational. The mass from a cephalohematoma can take weeks to resolve as the clotted blood is slowly absorbed. Over time, the bulge may feel harder as the collected blood calcifies. The blood then starts to be reabsorbed. Sometimes, the center of the bulge begins to disappear before the edges do, giving a crater-like appearance. This is the expected course for the cephalohematoma during resolution.[17][18][19][20] One should not attempt to aspirate or drain the cephalohematoma unless there is a concern for infection. Aspiration is often not effective because the blood has clotted. Also, entering the cephalohematoma with a needle increases the risk of infection and abscess formation. The best treatment is to observe the area alone and give the body time to reabsorb the collected fluid.

Usually, cephalohematomas do not present any problems to a newborn. The exception is an increased risk of neonatal jaundice in the first days after birth. Therefore, the newborn needs to be carefully assessed for a yellowish discoloration of the skin, sclera, or mucous membranes. Noninvasive measurements with a transcutaneous bilirubin meter can be used to screen the infant. A serum bilirubin level should be obtained if the newborn exhibits signs of jaundice. Rarely, calcification or ossification may occur in cases that are not resolved.[21][1] A skull x-ray or CT scan of the head is indicated in patients whose cephalohematomas have not resorbed within 6 weeks of birth.[2] Rather than absorbed, an ossified cephalohematoma has hardened and has a clearly defined outer and inner layer of the bone surrounding the lesion.[1][3] The inner layer of the ossified cephalohematoma is composed of the outer and inner table of the infant's calvarium. In contrast, the outer table comprises the infant's sub-pericranial bone derived from the elevated pericranium.[1] The contour of the ossified cephalohematoma's inner layer can either follow the calvarium's convex shape or become concave, encroaching upon the intracranial compartment.[1]

There is an ongoing debate regarding conservative management versus early surgical intervention for cephalohematoma, as there are currently no randomized controlled trials for reference. It has been suggested that early surgical intervention is not necessary if the cephalohematoma diameter is >50 mm unless other clinical indications are present.[10] In patients with later-stage ossification or calcification, the advocates for surgery argue that outcomes are superior with intervention at an earlier age due to the infant's natural molding process, decreased risk of elevated intracranial pressure, and cosmetic advantage.[2] A rare surgical indication for ossified cephalohematoma is persistent cosmetic disfigurement.[2] When indicated, ossified cephalohematoma can be treated safely and surgically with craniotomy or craniectomy and cranioplasty, yielding good outcomes.[1][3] The surgical technique involves resection of the overlying newly formed bone, the soft tissue mass, and the underlying original bone.[1] Following removal, the underlying depressed region is often sectioned into multiple pieces and is remodeled as a bone graft. There are multiple techniques for cranioplasty, each with favorable outcomes and minimal if any, residual evidence in the following years.[3]

Differential Diagnosis

When diagnosing cephalohematoma, it's crucial to consider other conditions that may present similarly. These differential diagnoses require careful evaluation to ensure accurate identification and appropriate management.

Caput Succedaneum

Caput succedaneum is scalp edema above the epicranial aponeurosis and beneath the overlying skin. The swelling in caput succedaneum is poorly defined and crosses suture lines. In contrast to cephalohematoma, caput succedaneum is present at birth and typically disappears in the following days.[2]

Subgaleal Hematoma

Subgaleal hematomas are located superficial to the periosteum and beneath the epicranial aponeurosis. Subgaleal hematoma may be associated with the rupture of emissary veins, becoming life-threatening, also presenting immediately after birth or a few hours later. In contrast to cephalohematoma, subgaleal hematomas are capable of crossing suture lines.

Prognosis

Most cases (approximately 80%) of cephalohematoma resorb within the first month of life.[1] Children typically do not have an associated neurologic deficit as the cephalohematoma is superficial to the calvarium and not in contact with the brain parenchyma.[1] In rare instances, cephalohematomas may calcify or lead to cosmetic deformities, but these occurrences are uncommon and typically do not result in long-term adverse effects on the infant's health.

Complications

Rare complications associated with cephalohematoma include anemia, infection, jaundice, hypotension, intracranial hemorrhage, and underlying linear skull fractures (5% to 20% of cases).[2][22][23] Cephalohematomas may calcify or lead to cosmetic deformities, though such occurrences are infrequent.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education play vital roles in the management of cephalohematoma. Expectant parents should be educated about the risk factors associated with cephalohematoma, such as prolonged labor or assisted delivery techniques like forceps or vacuum extractors. Providing information on the natural course of cephalohematoma, including its tendency to resolve without intervention, can alleviate parental anxiety and prevent unnecessary medical interventions. Clinicians should emphasize the importance of regular monitoring for any signs of complications, such as anemia or jaundice, and encourage prompt reporting of concerns. Newborns with a cephalohematoma and no other problems are usually discharged home with their families. Parents need to observe the bulge on the newborn's head for any changes, including an increase in size during the first week following birth. Parents also need to monitor for any behavioral changes such as increased sleepiness or crying, change in the type of cry, refusal to eat, and other signs that the infant might be in pain or developing a new problem. Recovery from a cephalohematoma requires little action except for ongoing observation. Educating caregivers on the signs of infection and the importance of maintaining proper hygiene around the affected area can help prevent potential complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key clinical pearls that guide effective care in the management of infants with cephalohematoma include the following:

- Cephalohematomas typically resolve spontaneously without intervention.

- Aspiration or drainage is ineffective and can lead to complications such as infection.

- Cephalohematoma must be differentiated from caput succedaneum and subgaleal hemorrhage.

- Regular monitoring for signs of complications, including anemia and jaundice, should be performed.

- The size, location, and any changes in the cephalohematoma must be documented to track progression accurately.

- Parents should be educated about the condition's natural course and the importance of close monitoring.

- The affected area should be handled gently to minimize discomfort and reduce the risk of complications.

- It is important to maintain proper hygiene to prevent infection and promote healing.

- Timely follow-up appointments should be ensured to assess resolution and address any concerns.

- Interprofessional collaboration is essential for comprehensive management and optimal outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing cephalohematoma necessitates a multifaceted approach involving various healthcare professionals to ensure patient-centered care, optimal outcomes, and safety. Physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, and other health professionals must collaborate effectively, utilizing various skills and strategies while fulfilling their responsibilities. This interdisciplinary collaboration begins with accurate diagnosis and differential diagnosis skills to differentiate cephalohematoma from similar conditions. Responsibilities encompass timely and thorough assessments, implementing evidence-based management protocols, and monitoring for complications.

Interprofessional communication is essential for sharing critical information, discussing treatment plans, and addressing patient and family concerns. Care coordination involves facilitating seamless transitions between healthcare settings, ensuring continuity of care, and educating the family to promote understanding and compliance. Before discharge, the newborn's family should understand the importance of monitoring the infant. The infant should be observed for any behavior change, feeding difficulties, emesis, and failure to thrive.[24] Collaboratively, healthcare professionals can enhance patient-centered care, improve outcomes, ensure patient safety, and optimize team performance in managing infants affected by cephalohematoma.