Continuing Education Activity

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most prevalent focal mononeuropathy, constituting 90% of all neuropathy cases. This condition occurs when the median nerve is compressed as it traverses the carpal tunnel, leading to entrapment neuropathy. The initial signs of CTS encompass pain, numbness, and paresthesias within the median nerve distribution. As CTS is a progressive condition in most patients, it can result in permanent loss of sensation and function in the hand if it is not adequately identified and treated. This activity reviews the etiology, presentation, evaluation, and management of CTS while highlighting the collaborative efforts of the interprofessional healthcare team in evaluating and treating the condition.

Objectives:

Identify the early signs and symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome, including pain, numbness, and paresthesias in the median nerve distribution, during patient assessments.

Select appropriate surgical intervention as a treatment option for patients with severe or refractory carpal tunnel syndrome, considering individual patient characteristics and preferences.

Implement evidence-based diagnostic tools and tests, such as electromyography and nerve conduction studies, to confirm carpal tunnel syndrome diagnosis when indicated.

Collaborate with interprofessional healthcare teams and coordinate follow-up care while monitoring patients with carpal tunnel syndrome for the long-term management of the condition.

Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) occurs when the median nerve is compressed as it traverses the carpal tunnel. The primary factor contributing to the onset of CTS is the elevated pressure within the carpal tunnel. The typical initial signs of CTS include pain, numbness, and paresthesias, which affect the first 3 digits and the lateral half of the fourth digit.[1] Symptoms of CTS can exhibit variability, with pain manifesting at the wrist, involving the entire hand, and potentially radiating up the forearm or extending beyond the elbow. Pain associated with CTS does not typically extend to the neck. As the condition advances, individuals may experience hand weakness, diminished fine motor coordination, clumsiness, and eventual atrophy of the thenar muscles.[1]

Initially, symptoms associated with CTS frequently manifest at night while lying down and tend to improve during the daytime. Over time, the majority of patients begin to encounter symptoms during the day, particularly when engaged in repetitive activities such as drawing, typing, or playing video games. In advanced cases, these symptoms may become persistent or constant.

Occupations involving frequent computer use, exposure to vibrating equipment, or repetitive movements significantly elevate the risk of developing CTS for individuals.[2][3][4] Obesity, genetic predisposition, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and pregnancy also contribute to the risk of developing CTS.

Treatment options for CTS depend on the severity of the disease. In most cases, patients should undergo an initial trial of conservative treatment. Individuals with severe disease or who do not respond to traditional treatment measures should consider surgical intervention.

Etiology

The carpal tunnel is a narrow passageway in the wrist formed by the transverse carpal ligament at its upper boundary and the carpal bones at its lower boundary. The carpal tunnel accommodates 9 flexor tendons and the median nerve, which traverses through it. CTS develops due to mechanical trauma, elevated pressure, and ischemic damage affecting the median nerve.

The normal pressure within the carpal tunnel ranges from 2 to 10 mmHg.[1] However, the extension or flexion of the wrist causes the pressure to increase 8 to 10 times the normal level. If a nerve is compressed repeatedly, it can lead to demyelination occurring at the site of compression. Endoneurial edema develops due to a disruption in blood flow to the endoneurial capillary system.

Although the exact etiology of increased carpal tunnel pressure remains uncertain, several conditions elevate the risk of CTS in patients. The risk of developing CTS is more likely when the carpal tunnel is modified, fluid equilibrium within the body is altered, or direct neuropathic factors are present.

Examples of the risk factors associated with CTS include:

- Dislocation or subluxation of the carpus

- Fractures or skewed consolidation of the distal radius

- Wrist arthrosis, inflammatory arthritis, and infectious arthritis

- Acromegaly

- Cysts or tumors within the tunnel

- Pregnancy

- Menopause

- Obesity

- Kidney failure

- Hypothyroidism

- Use of oral contraceptives

- Congestive heart failure

- Diabetes

- Alcoholism

- Vitamin deficiency or toxicity

- Exposure to toxins

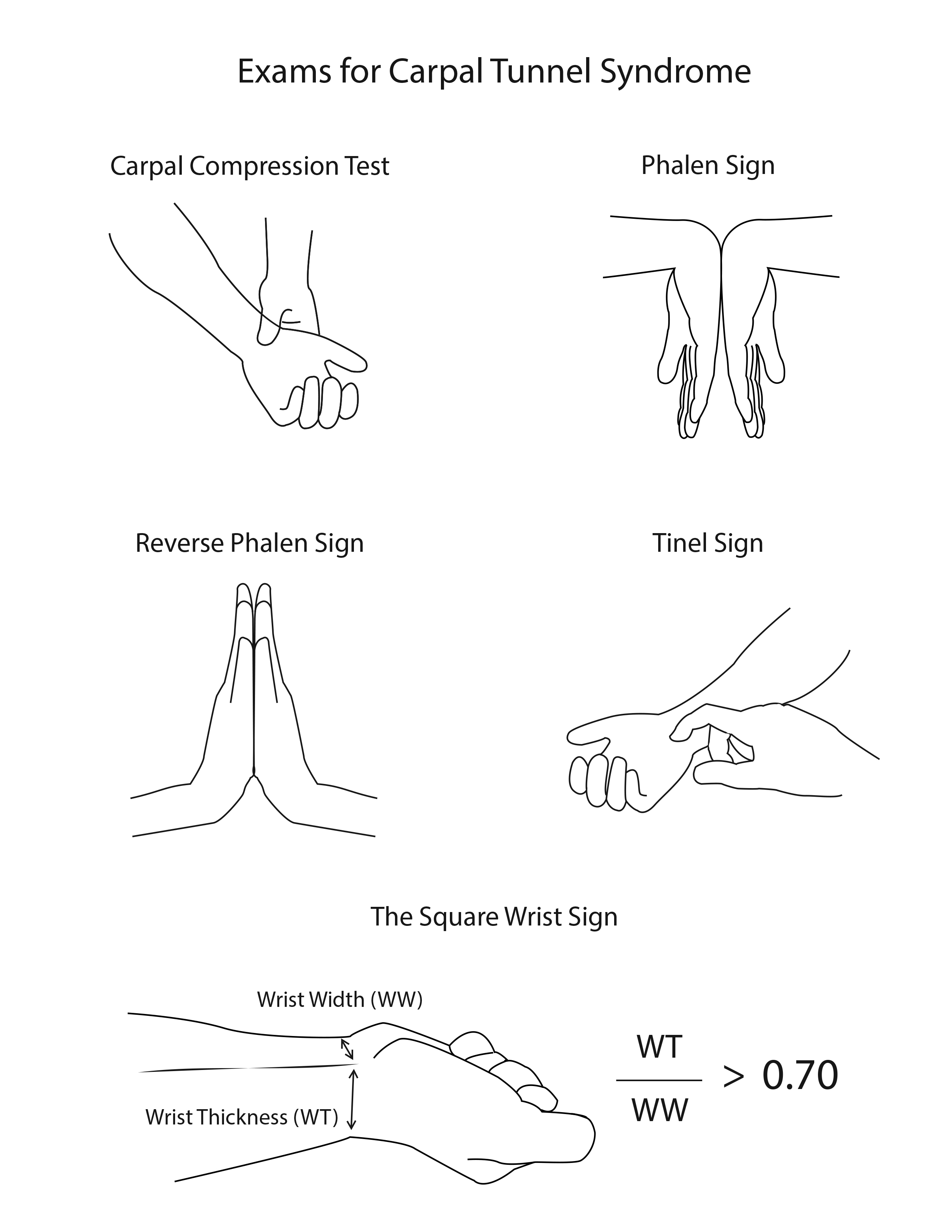

The square wrist test measures the ratio of wrist thickness to wrist width, and any value exceeding 0.7 indicates a higher risk of developing CTS.

Epidemiology

The incidence of CTS in the general population ranges from 1% to 5%. CTS is more prevalent in females than males, with a 3:1 female-to-male ratio. The risk of developing CTS is doubled in individuals who are obese. [5][6][7] CTS is uncommon in children and typically manifests in adults aged 40 to 60.

Pathophysiology

CTS is a multifactorial condition typically arising from a combination of patient-specific, occupational, social, and environmental factors. Therefore, a single, specific cause is usually not identified unless a clear physical finding directly explains the patient's symptoms.

The pathology associated with CTS generally results from a combination of compression and traction affecting the median nerve. The compressive element involves a detrimental cycle characterized by increased pressure, obstruction of overall venous outflow, localized edema buildup, and impairment of the median nerve's intraneural microcirculation. Nerve function is compromised when lesions develop on the myelin sheath and axon, causing inflammation and loss of normal physiological protective and supportive functions of surrounding connective tissues. The changes in the nerve's structural integrity worsen the dysfunctional environment.

Repeated traction and wrist movements exacerbate the dysfunctional environment, leading to further nerve injury. In addition, any of the 9 flexor tendons passing through the carpal tunnel can become inflamed and compress the median nerve.[8] Sensory fibers are often affected before motor fibers, and autonomic nerve fibers carried within the median nerve may also become affected.

History and Physical

Patients with CTS frequently report experiencing numbness, tingling, and pain in the thumb and second, third, and radial portions of the fourth digits, which tend to worsen at night. The distribution of these symptoms can vary, ranging from localized discomfort at the wrist, encompassing the entire hand, radiating to the forearm, or extending upward beyond the elbow to the shoulder.

Initially, symptoms are intermittent and associated with activities such as driving, reading newspapers, and painting. Symptoms that worsen at night indicate CTS, especially if the patient experiences relief by shaking the hand or wrist. Advanced disease is marked by progression to permanent sensory loss, muscle weakness, clumsiness, and challenges in tasks such as opening doorknobs and buttoning clothes (see Image. Untreated Carpal Tunnel Syndrome). Although bilateral CTS is frequently observed, the dominant hand is typically affected initially. Numbness in the fifth digit, extending to the thenar eminence, dorsum of the hand, or neck, suggests an alternative diagnosis.

During the physical examination, sensory loss or weakness within the median nerve distribution may become apparent (see Image. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome). Sensory loss typically spares the thenar eminence since the palmar sensory cutaneous nerve bypasses the carpal tunnel rather than passing through it. Additional possible findings include diminished strength in thumb abduction and opposition and atrophy of the thenar eminence.

Various provocative tests exhibit varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity. Several maneuvers are accessible to attempt the reproduction of CTS symptoms (see Image. Carpal Tunnel Physical Exam). The results of these tests offer limited sensitivity and specificity when used individually. Therefore, it is advisable to integrate these results with the patient's clinical history for a more comprehensive assessment.

The most dependable provocative maneuver, known as the carpal compression test, involves applying steady pressure directly over the carpal tunnel for 30 seconds (see Image. Carpal Tunnel Physical Exam). A positive test is evident when paresthesias or pain arises within the median nerve distribution during the carpal compression test. This test is associated with a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 83%.

The Phalen test, also known as the reverse prayer, involves instructing the patient to fully flex their wrists by placing the dorsal surfaces of both hands together, with the elbows flexed, and holding this position for 1 minute (see Image. Carpal Tunnel Physical Exam). A positive test is marked by pain and paresthesias in the fingers innervated by the median nerve during the Phalen test. This test exhibits a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 73%.[9][10]

In the Tinel test, a healthcare professional taps directly over the carpal tunnel to elicit a response from the median nerve. The test is considered positive if symptoms manifest. The Tinel test demonstrates a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 77%.[10]

Evaluation

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of mild CTS typically do not require additional diagnostic studies. Except for pregnant individuals, patients experiencing atypical symptoms, pain disrupting sleep, persistent numbness or weakness in the hand, or any impairment in hand function should undergo electrodiagnostic testing, including nerve conduction studies. Electromyography (EMG) may also be incorporated to assist in surgical decision-making and rule out alternative diagnoses. EMG can reveal the presence of residual axonal integrity even in cases where no sensory or motor components are elicited. Abnormalities detected on electrodiagnostic testing, associated with specific symptoms and signs, are regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing CTS.

Electrodiagnostic testing can also evaluate the severity of nerve damage and provide insight into the prognosis, as clinical symptoms may not always accurately reflect the actual extent of median nerve damage. CTS is typically categorized into 3 severity levels—mild, moderate, and severe. In cases of mild CTS, patients exhibit only sensory abnormalities on electrophysiological testing, whereas in moderate CTS, patients have both sensory and motor abnormalities.

Imaging is only necessary in cases of a suspected structural abnormality. Potential structural abnormalities such as tumors or ganglion cysts may warrant further investigation. Ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging are the preferred imaging modalities for this purpose.

Treatment / Management

The primary treatment approach for mild CTS symptoms involves conservative therapy, including nighttime wrist splinting or glucocorticoid injections. Wrist splints are considered the initial preference for the treatment, and they are typically worn during the nighttime to maintain a neutral wrist position.[11] Patients should undergo a follow-up evaluation within 1 to 2 months. If their symptoms show improvement, it is advisable to continue splinting; however, if improvement is lacking, the option of combining splitting with other therapeutic approaches should be considered.

Although glucocorticoid injections provide faster relief, they ultimately yield comparable long-term outcomes when compared to splinting.[12][11] A glucocorticoid injection is a viable first-line alternative to nighttime wrist splinting. Methylprednisolone, at a dosage of 20 to 40 mg, is mixed with 1% lidocaine and injected into the carpal tunnel using either ultrasound guidance or anatomic landmarks. Anticipated relief typically lasts for about 3 months. For each wrist, it is advisable to limit injections to a maximum of every 6 months. Notably, assessing the patient for surgical intervention is advisable if there is no response to 1 or 2 injections. Potential adverse effects of glucocorticoid injections include exacerbation of median nerve compression, accidental injection into the median or ulnar nerves, and the risk of digital flexor tendon rupture.[13]

When initial conservative therapy proves ineffective, additional options may involve a combination of splinting with a glucocorticoid injection. Patients who prefer to avoid injections may find relief from a brief course of oral prednisone, typically administered at a dosage of 20 mg daily for 10 to 14 days. Extended use of oral glucocorticoids is discouraged due to potential adverse effects.

Referral to a specialized hand therapist can be beneficial, as they can provide techniques such as carpal bone mobilization, nerve- and tendon-gliding exercises, and ultrasound therapy. According to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, oral agents have demonstrated no superior efficacy over placebo in treating CTS. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and diuretics are found to be ineffective in CTS management.

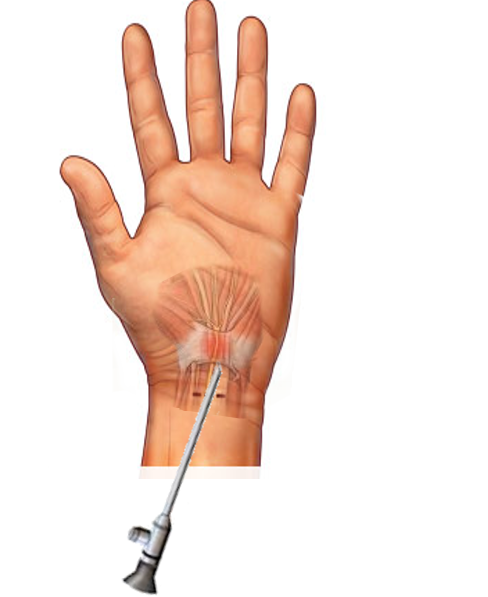

Patients unresponsive to conservative treatments or those with severe CTS confirmed through electrophysiological testing may require surgical intervention. Electrophysiological testing is a prerequisite for carpal tunnel release surgery, which serves as the definitive treatment for CTS and can be performed using an open or endoscopic approach. This minimally invasive procedure relieves pressure on the median nerve by making a small incision in the transverse carpal ligament. Patients can often be discharged on the same day without staying overnight in the hospital.[14][15][16] In general, surgery offers more favorable long-term outcomes compared to conservative therapy.[17] Although initial success rates surpass 90%, long-term results are somewhat less promising, with an approximate success rate of 60% at the 5-year mark.

Differential Diagnosis

The presentation of CTS can resemble various other musculoskeletal and nervous system disorders. When evaluating a patient with suspected CTS, the following conditions should be considered:

- Brachial plexopathy

- Cervical myofascial pain

- Cervical spondylosis

- Compartment syndrome

- Ischemic stroke

- Mononeuritis multiplex

- Multiple sclerosis

- Median neuropathy in the forearm

- Motor neuron disease

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Overuse injury

- Traumatic brachial plexopathy

- Radiation-induced brachial plexopathy

- Neuropathies

- Tendonitis

- Tenosynovitis

- Thoracic outlet syndrome

Prognosis

CTS typically progresses over time and has the potential to result in permanent damage to the median nerve. The syndrome exhibits some degree of recurrence, even after surgical intervention, in up to one-third of patients after 5 years. Approximately 70% to 90% of mild-to-moderate CTS cases positively respond to conservative management. Nevertheless, many patients may progress to the point where surgical intervention becomes necessary. Patients with CTS that are secondary to diabetes or a wrist fracture often have a less favorable prognosis compared to individuals with no apparent underlying cause. Patients with normal electrophysiological studies have much less favorable operative outcomes and more complications than individuals with abnormalities on these tests. The presence of axonal loss detected on electrophysiological testing indicates a poor prognosis.[18]

Complications

Complications of CTS can arise from the condition itself or the treatments administered. CTS may lead to irreversible median nerve damage, resulting in permanent impairment and disability. Muscle weakness and atrophy at the base of the thumb can cause reduced dexterity. Patients affected by this condition may also suffer from chronic wrist and hand pain, potentially progressing to the development of complex regional pain syndrome.

The most frequent complication of carpal tunnel surgery is the development of a neuroma in the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. Patients may also experience hypertrophic scars, joint stiffness, dysesthesias, and incomplete resolution of their symptoms.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Splinting and proper hand ergonomics play a significant role in the rehabilitative efforts for CTS. Therapists utilize ultrasound, iontophoresis, and paraffin wax to reduce swelling and alleviate pain. Studies have yielded mixed results regarding the effectiveness of these modalities in improving outcomes. Further high-quality research is required to assess the efficacy of these interventions thoroughly. Using nerve-gliding exercises, massage, and trigger point release has shown significant improvements in muscle strength, pain reduction, and enhanced nerve conduction based on available data. The treating physical or occupational therapist should consider these approaches for implementation.[19][20][21]

Deterrence and Patient Education

CTS develops when there is compression of the median nerve within the wrist. Although the exact reason for nerve compression remains uncertain, experts theorize that a combination of genetic predisposition, specific health conditions, and environmental factors collectively contribute to the onset of CTS.

Symptoms of CTS include pain, numbness, tingling, and possibly weakness affecting the first 3 digits and the portion of the ring finger nearest to the thumb. These symptoms can manifest in either one hand or both and may extend up the arm. Therefore, individuals with CTS may experience a sense of clumsiness, and tasks such as buttoning clothes and turning doorknobs may become challenging.

Females are at a higher risk of experiencing CTS than males. Furthermore, individuals employed in occupations that entail repetitive hand movements or the use of vibrating equipment face an elevated risk of developing CTS. Conditions such as diabetes, obesity, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and pregnancy elevate the risk of developing CTS.

A healthcare professional can diagnose patients with mild symptoms of CTS without the need for additional testing. Patients with unusual or severe symptoms should undergo electrodiagnostic tests. These electrical nerve tests can provide healthcare professionals with information about the proper transmission of electrical signals along the median nerve and the appropriate response of hand and wrist muscles to these signals.

The standard initial treatments for CTS typically involve wearing a wrist splint at night or receiving a steroid injection directly into the wrist. In some cases, patients may be prescribed oral steroids. Splints are particularly helpful during pregnancy since the symptoms generally resolve after birth. Seeking care from a specialty-trained hand therapist may also be beneficial.

Healthcare professionals recommend surgery for patients with severe symptoms or those who do not experience improvement with conservative treatment. The surgical procedure entails the release of the ligament over the carpal tunnel, creating additional space.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As CTS is the most prevalent nerve entrapment neuropathy, individuals affected will seek care from various healthcare specialties. Symptoms can become debilitating if not promptly addressed. Clinicians from various specialties, including obstetrics, orthopedics, neurology, primary care, endocrinology, and physical or occupational therapy, are critical in diagnosing and managing CTS. Combined therapy may offer more substantial benefits than any single treatment. Therefore, healthcare professionals must educate patients about the risks, benefits, and efficacy of various treatment modalities of CTS and help them establish realistic expectations regarding their treatment outcomes. Effective communication among healthcare team members is essential in facilitating combined therapies, patient education, and timely treatment to support patients in regaining normal function. The collaborative interprofessional team approach is instrumental in improving outcomes for CTS patients.[22][23]