Continuing Education Activity

Pulmonary carcinoid tumors are uncommon neuroendocrine epithelial malignancies accounting for less than 1% of all lung cancers. They divide into two subcategories: typical carcinoids and atypical carcinoids. Typical carcinoids and atypical carcinoids are, respectively, low- and intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors. Approximately 80% of pulmonary carcinoids occur centrally, and 20% are peripheral. All bronchial carcinoids are malignant and have the potential to metastasize. This activity reviews the cause and pathophysiology of lung carcinoids and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its evaluation and management.

Objectives:

Clinicians must differentiate pulmonary carcinoids from other lung pathologies, such as small-cell lung carcinoma or metastatic tumors.

Clinicians should be able to implement evidence-based guidelines for the surgical management of pulmonary carcinoids, including determining the extent of surgery and adjuvant treatment options.

Clinicians should apply appropriate therapeutic interventions, including surgical resection and adjuvant therapies, based on the characteristics and stage of the pulmonary carcinoid tumor.

Clinicians should collaborate with multidisciplinary teams, including pathologists, radiologists, and oncologists, to ensure comprehensive and coordinated care for patients with pulmonary carcinoids.

Introduction

Carcinoid tumors are rare malignant neuroendocrine epithelial tumors that can develop at various sites in the body, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, ovaries, adrenal glands, and thyroid. Among all carcinoid tumors, those arising in the lungs account for approximately 25% of cases, making them the second most common site. However, pulmonary carcinoids account for less than 2% of all lung cancers.[1]

Pulmonary carcinoids can be classified into 2 subcategories: typical and atypical carcinoids, with the latter, comprising only 10% to 15% of cases. Typical carcinoids are considered low-grade neuroendocrine tumors, while atypical carcinoids are classified as intermediate-grade. The grading criteria for these tumors are defined by the World Health Organization and will be reviewed in the histopathology section of this activity.

Approximately 80% of pulmonary carcinoids are located centrally within the lung, while 20% are in peripheral regions.[2] All bronchial carcinoids are malignant and have the potential to metastasize.[3] Unlike many other lung cancers, carcinoids are not associated with smoking. These tumors are typically small and tend to occur in central locations. Lymph node involvement is observed in less than 10% of cases, and carcinoid syndrome, a collection of symptoms caused by certain chemicals released by the tumor, is rare, occurring in less than 3% of cases.

Etiology

The precise causes of carcinoid tumors are not fully understood, and although some studies suggest a potential link with smoking, the causal relationship remains uncertain. Evidence indicates that more patients with atypical carcinoids are smokers than typical carcinoid tumors. Certain air pollutants and chemicals have also been identified as risk factors in other research studies.[4]

In rare cases, lung carcinoids can occur associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type1 (MEN-1) syndrome. Furthermore, there have been reports of sporadic instances in which the MEN-1 gene is found to be inactivated, suggesting a potential genetic component to the development of these tumors.[5]

Epidemiology

Carcinoid tumors are uncommon malignancies that can affect the lungs. While they can occur at any age between 5 and 90 years, the average age of presentation is around 50. Notably, atypical carcinoids present approximately 10 years earlier than typical carcinoids. About 8% of these tumors are diagnosed during the second decade of life, making them the most common primary pulmonary tumor in childhood.

Some data suggest a higher incidence of carcinoid tumors among individuals of white ethnicity and woman than men.[6]

In recent decades, the incidence of carcinoid tumors, including pulmonary carcinoids, has shown an upward trend. This increase can be attributed to several factors, including advancements in medical investigations and improved detection rates.[7]

Pathophysiology

The precise mechanisms underlying the development and progression of carcinoid tumors are not fully understood. However, in some cases, it is believed that these tumors may arise from proliferating pulmonary neuroendocrine cells via a condition known as diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) and tumorlets.[8]

Carcinoid tumorlets are histologically identical to carcinoids but are smaller, measuring <0.5 cm in size. The exact significance of tumorlets is unknown but can be associated with inflammatory or fibrosing conditions. DIPNECH is a rare condition characterized by the widespread presence of pulmonary carcinoid tumorlets and, occasionally, tumors. This condition is exclusively reported in women and can cause symptoms when the lungs are extensively involved.[9]

Histopathology

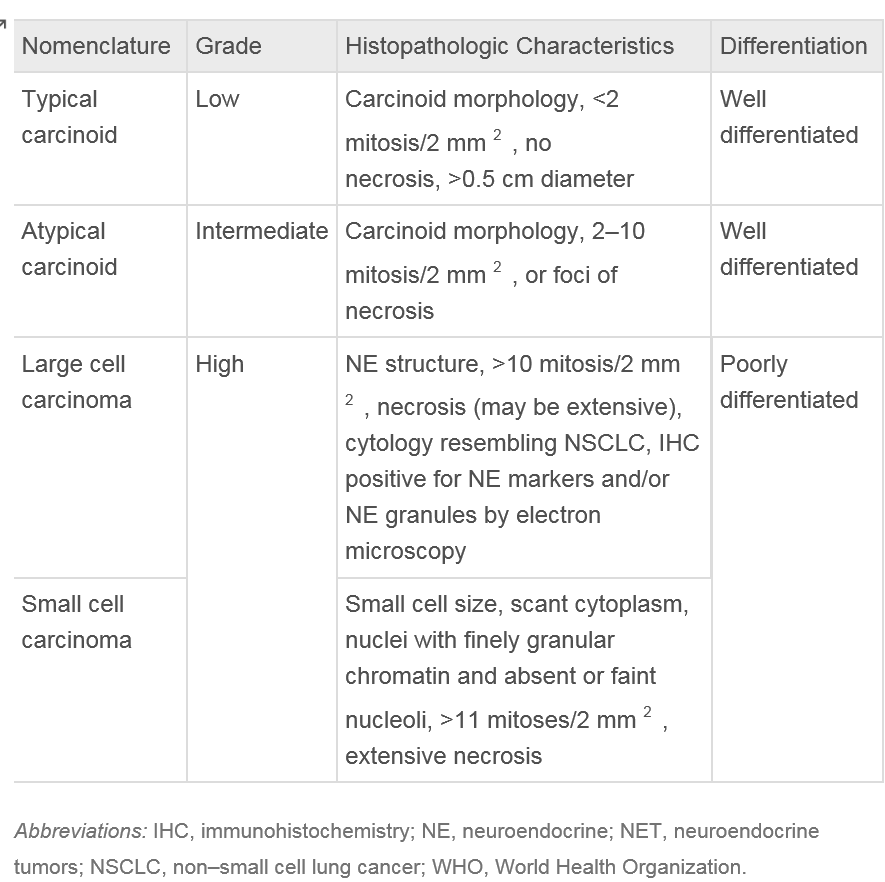

Lung carcinoids belong to a group of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) originating in the lungs. These NETs can manifest as typical low-grade, well-differentiated, slow-growing tumors or atypical high-grade, poorly differentiated carcinomas. Despite their differing grades, both types of NETs share standard features, including the ability to synthesize neuropeptides and the presence of submicroscopic cytoplasmic dense-core structures.[10]

Macroscopic Findings

Central carcinoid tumors exhibit well-defined boundaries and have a round to oval shape. They can be either sessile or pedunculated. Histologically, these tumors display salt and pepper chromatin and moderate to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. They often occupy and fill the bronchial lumen.[11]

As central carcinoids grow, they may extend between the cartilaginous plates into adjacent tissues. Carcinoids range in size from 0.5 to 9.5 cm. On average, atypical carcinoids are larger than typical carcinoids.[11]

Histopathology

The growth patterns of carcinoid tumors suggest neuroendocrine differentiation. The most common patterns observed are organoid and trabecular arrangements. However, other growth patterns may also be present, such as rosette formation, papillary growth, pseudo-glandular growth, and follicular growth. The tumor cells typically appear uniform, with finely granular nuclear chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and moderate to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm.[12]

The stroma surrounding carcinoid tumors is highly vascularized but can also display extensive hyalinization, cartilage, or bone formation. There have been reports of stromal amyloid deposition and prominent mucinous stroma within these tumors.

Typical carcinoids are characterized by having less than 2 mitoses per 2 mm² and lacking necrosis. In contrast, atypical carcinoids exhibit similar histological features as typical carcinoids but are defined by the presence of 2 to 10 mitoses per 2 mm² and necrosis.[13] Necrosis in carcinoids is usually punctate. Mitotic activity should be counted in the area with the highest number of mitoses, with as many viable tumor cells as possible, and the counting should be reported per 2 mm² rather than based on a specific number of high-power fields.[12]

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry is crucial in diagnosing carcinoid tumors, especially in small biopsy samples. A recommended antibody panel for immunostaining includes chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and CD56. However, none of these markers can differentiate between typical and atypical carcinoids. Additionally, most carcinoids react to pan-cytokeratin antibodies, commonly used to identify epithelial cells. Some peripheral tumors may also exhibit staining with thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1), although this marker is less specific for carcinoid tumors.

In the evaluation of biopsy or cytology samples, the Ki67 labeling index is valuable, especially in cases where crush artifacts make assessing the mitotic index challenging. By measuring the Ki67 labeling index, which indicates the percentage of cells undergoing active cell division, misdiagnosis of carcinoid tumors as high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas can be avoided.[12]

History and Physical

Approximately 25% of individuals with lung carcinoid tumors may not experience any noticeable disease symptoms. These tumors are often incidentally discovered during diagnostic tests or screenings conducted for unrelated conditions.

The most common presenting symptoms of bronchopulmonary carcinoid tumors are:

- Coughing or wheezing

- Hemoptysis

- Symptoms related to the consequences of collapse or pneumonia distal to airway obstruction.[2] Sometimes patients may present with stridor.

Since pulmonary carcinoid tumors are primarily carcinoid tumors, some patients may present with symptoms of carcinoid syndrome:

- Facial flushing

- Shortness of breath

- High blood pressure

- Weight gain

- Hirsutism

- Asthma-like symptoms

Small carcinoids may be asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally during medical examinations or imaging tests conducted for unrelated reasons.

In most cases, pulmonary carcinoid tumors do not exhibit endocrine symptoms at the clinical level. These tumors are often considered "endocrinologically silent" because they do not commonly produce significant amounts of hormones or bioactive substances that result in noticeable clinical effects. Clinical syndromes secondary to peptide production are uncommon; they include carcinoid syndrome, Cushing syndrome, and acromegaly.[2]

Evaluation

Biochemical Evaluation

Plasma chromogranin A measurement, blood count, electrolytes, and liver and kidney function are tests indicated in the diagnostic process and follow-up of carcinoids[14].

Specific tests are performed when symptoms suggesting hormonal secretion are present. They include[15]:

- Urinary 5-hydroxy indoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), a metabolite of serotonin, is often elevated in patients with carcinoid syndrome

- Serum cortisol levels, 24-hour urine free cortisol levels will be elevated

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels in patients with suspected Cushing’s disease. These will be increased.

- Plasma growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) and insulin growth factor (IGF)-I levels are indicated in patients with signs of acromegaly. These will be elevated.

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy plays a significant role in diagnosing lung carcinoids, as these tumors are typically centrally located and visible during endoscopic evaluation.[16] Bronchoscopic evaluation with a biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing pulmonary carcinoids. However, bronchoscopic biopsy carries a risk of hemorrhage due to the highly vascular nature of these tumors.

Radiological Assessment

Carcinoids can be visible on a standard chest X-ray in 40% of cases. However, the gold standard for the radiological detection and evaluation of lung carcinoids is computed tomography (CT) with intravenous (IV) contrast.

Both chest X-ray and CT scans typically show well-defined, round, and sometimes slightly lobulated masses in cases of lung carcinoids. Central carcinoid tumors can exhibit calcification. When the tumor involves the bronchial airway, secondary effects can be observed, including atelectasis, bronchiectasis, and areas of hyperlucency on CT scans.[17]

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) may distinguish carcinoid tumors from atypical carcinoids. This technique is most helpful in discerning carcinoids from high-grade neuroendocrine tumors such as small-cell or large-cell neuroendocrine tumors.[18] Carcinoids exhibit low-to-moderate activity on PET scanning.

Octreotide single-photon emission CT (SPECT) and other novel imaging techniques, such as gallium-labeled somatostatin analogs, have shown promise in improving the detection sensitivity of lung carcinoids.[19] Imaging for somatostatin receptors using Indium-111-labeled-octreotide may increase the sensitivity for diagnosis, staging, and follow-up for recurrence.[20]

Treatment / Management

Surgery

Surgical resection is the primary treatment of choice for patients with lung carcinoids.[15] The extent of the resection depends on several factors, including the type of carcinoid (typical or atypical) and the involvement of surrounding lung tissue.

Extensive resections may be necessary in cases of atypical carcinoids or significant destruction of the distal lung parenchyma. The surgical technique of choice is often lobectomy. In some cases, sleeve resection or wedge resection may also be performed.

Since carcinoids often arise from the main or lobar bronchi, bronchoplastic procedures are usually required during surgical resection to preserve lung function and maintain proper airway continuity.

A wedge resection is favored in peripheral carcinoids and is often sufficient.[2]

Adjuvant Therapy

The use of adjuvant therapy in pulmonary carcinoids is a topic of ongoing debate, and there is no consensus on its role in managing these tumors.[2] The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend considering adjuvant cisplatin and etoposide chemotherapy with or without radiation in stage III atypical carcinoids.[2] The European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society also advocates adjuvant treatment in atypical carcinoids with positive lymph nodes but not for typical carcinoids.[2]

Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapy is used for advanced or metastatic pulmonary carcinoids. The choice of systemic treatment depends on several factors, including the tumor grade, the extent of metastasis, and individual patient characteristics.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of pulmonary carcinoids include:[12]

- Metastatic carcinoids from elsewhere, especially those originating from the gastrointestinal tract

- Small cell lung carcinoma

- Salivary gland-type tumors

- Metastases of lobular breast carcinoma, paraganglioma, and glomangioma

- Tumorlets

Surgical Oncology

Stage I to III carcinoid tumors are treated through surgical resection. It is the only curative treatment modality for pulmonary carcinoids. The extent of surgical resection depends on the tumor characteristics, location, and stage of the disease.

For stage I pulmonary carcinoids, which are localized and confined to the lung without the involvement of lymph nodes, surgical resection with lobectomy is often the treatment of choice. However, pneumonectomy or bilobectomy may be needed for centrally located lesions.[21] In cases where the tumor is smaller and located in the peripheral regions of the lung, segmentectomy or wedge resection may be considered.

Typical carcinoids, which have favorable histology and are localized without lymph node involvement, can often be managed with more limited resections and still achieve a cure. However, for atypical carcinoids, which have a higher risk of recurrence and metastasis, the surgical guidelines for non-small cell lung cancer are followed. Lobectomy is often considered for lesions smaller than 2 cm, and mediastinal lymph node dissection is done in all patients.

The role of mediastinal lymph node dissection in pulmonary carcinoids is still debatable, with limited evidence supporting its benefits in reducing local recurrence and improving survival. However, performing mediastinal lymph node dissection in all patients with pulmonary carcinoids is generally recommended, as it allows for accurate staging and helps guide further treatment decisions.[22]

Historically, open thoracotomy was the standard approach for pulmonary resection. In recent years, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) has gained popularity and become the preferred technique for resectioning pulmonary carcinoids.

The advantages of VATS include a reduction in morbidity, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery. Numerous studies have demonstrated the short-term and long-term benefits of VATS, making it the standard approach.[23][24]

Even in cases where an open thoracotomy is performed, the technique has evolved and improved. The incisions are smaller and muscle-sparing, resulting in reduced trauma to the chest and enhanced postoperative recovery.

As most carcinoid tumors are intrabronchial in location and tend to grow slowly, there has been an emphasis on developing parenchymal-sparing procedures for pulmonary resection. These include sleeve lobectomy and sleeve pneumonectomy, which have been performed with excellent long-term results.

Radiation Oncology

Carcinoid tumors are less responsive to radiotherapy than small-cell lung cancer (SCLC); therefore, it has a limited role in managing pulmonary carcinoids. However, in some instances, radiotherapy may be used as part of the treatment approach for pulmonary carcinoids.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend using adjuvant cisplatin and etoposide with or without radiation in stage III atypical carcinoids.[2] The European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society also advocates adjuvant treatment in atypical carcinoids with positive lymph nodes but not for typical carcinoids.[2] Chemoradiotherapy is often recommended for the treatment of locally advanced, unresectable diseases. A commonly used dose for radiotherapy in this setting is 60 Gy.

Medical Oncology

Adjuvant chemotherapy is not recommended for stage I to III carcinoid tumors as the risk of recurrence is low. It is, however, recommended for stage III atypical carcinoids.[2] If surgery is not an option for locally advanced, atypical carcinoid, chemoradiotherapy is recommended.

Chemotherapy forms the backbone of metastatic stage IV carcinoids, although the efficacy data is lacking due to rare incidences. The independent trials of pulmonary carcinoids are uncommon. Close radiological surveillance can be offered for low tumor burden and low-grade carcinoids. Systemic therapy is initiated at the time of progression. Various options for systemic therapy include somatostatin analogs, chemotherapy, mTOR inhibitors, and anti-VEGF agents.

Somatostatin Analogs

The use of somatostatin analogs in pulmonary carcinoids is extrapolated from the experience with gastrointestinal tract carcinoid tumors. Small studies show that despite low response rates, somatostatin receptor-targeted therapies improve the symptoms of carcinoid syndrome and disease progression. The PROMID study demonstrated the activity of long-acting somatostatin in midgut NETs. Compared to the placebo, time to disease progression was prolonged, but overall survival was the same.[25]

Chemotherapy

Carcinoid tumors are less responsive to chemotherapy compared to more aggressive counterparts like SCLCs. However, without more effective alternatives, chemotherapy regimens used in SCLC are sometimes used to treat advanced or metastatic pulmonary carcinoids. Cisplatin and etoposide showed an overall response rate of 20% in small case series.[26] Temozolomide and capecitabine combination has also demonstrated activity in advanced pulmonary carcinoids.[27]

Mammalian Target of Rapamycin-Directed Therapy (mTOR)

mTOR pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of NETs. RADIANT-4 trial studied the role of everolimus in the non-functional lung and gut NETs. Out of 90 patients with lung carcinoids, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 9.6 months for everolimus compared to 3.6 months for placebo. The toxicities of everolimus included hyperglycemia, infections, and stomatitis. [28]

Staging

In pulmonary carcinoid tumors, the classification system designates typical carcinoids as low-grade.[29] The staging of typical and atypical carcinoids follows the TNM staging of lung cancer.[30] Most typical carcinoids are stage 1a.[29]

Atypical carcinoids as classified as intermediate grade. Atypical carcinoids are usually at a higher stage at presentation than typical carcinoids.[29]

Prognosis

The prognosis of pulmonary carcinoids is influenced by tumor size, grade, disease stage, and older age. The 5-year survival rate depends on the stage of the disease. Generally, the prognosis improves with earlier stage diagnosis. The approximate 5-year survival rates for stages I to IV are 93%, 84%, 75%, and 57%, respectively.

Typical carcinoids have a better prognosis than atypical cases. The five-year survival rate for patients with typical carcinoids is 90%, while for atypical carcinoids, it is around 60%.

Nodal involvement is considered a poor prognostic factor. However, the impact of nodal involvement on prognosis is still not definitely established.

Other factors associated with a poorer prognosis in typical lung carcinoid tumors include incomplete resection, age, gender, tumor site (central versus peripheral), TNM stage, and performance status. A 2015 European Association of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) Neuroendocrine Tumours Working Group article revealed higher mortality for patients with increased age, male gender, peripheral tumor location, higher TNM stage, and lower functional status.[31]

Complications

Carcinoids often involve major bronchi. This could lead to massive, potentially life-threatening hemoptysis.

While carcinoid syndrome, Cushing syndrome, and acromegaly are potential complications of carcinoid tumors, they are relatively infrequent. These syndromes occur when the tumor produces ectopic peptides or hormones that lead to specific clinical manifestations such as flushing, diarrhea, wheezing, and hormonal imbalances.[32][33] These symptoms are more commonly associated with gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors than pulmonary carcinoids.

Smokers have an increased risk of second primary lung or other smoking-related cancer. Though rarely given, chest irradiation increases the risk of secondary cancers and coronary artery disease. Other tobacco-related diseases like cardiovascular disease, stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease also impact survival.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated regarding the disease's potential recurrence and metastatic spread. Oncologic follow-up is conducted similarly to that for pulmonary carcinoma after resection. Patients are followed clinically and by plain chest radiograph examination or CT every 2 to 3 months for the first year after surgery. Yearly follow-up is then advised for 10 years.

The current guidelines recommend no surveillance for node-negative low-grade (typical) carcinoid tumors unless the tumor is greater than 3 cm in size, close margins are noted on resected tumor pathology, or if the multifocal disease is present.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Despite having a good prognosis, carcinoid tumors can be challenging to diagnose due to their non-specific symptoms. Patients with carcinoid tumors may present with cough, fever, and shortness of breath. The underlying cause could be due to many diagnoses, including chronic obstructive airway disease, pneumonia, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, adenocarcinoma lung, squamous carcinoma lung, and heart failure. In some cases, the tumor may be discovered incidentally during imaging studies for unrelated reasons.

Given the diverse differential diagnoses and the need for a definitive diagnosis, a biopsy is typically necessary. The diagnostic process may involve collaboration between pulmonologists, radiologists, and pathologists to evaluate and interpret clinical findings, imaging studies, and tissue samples appropriately.

Meticulous staging and planning are required before surgery. For smokers, smoking cessation and rigorous chest physiotherapy should be advised. Post-operative calculation of pulmonary reserve requires careful evaluation by a respiratory physician.

The interventional radiologist could help in the biopsy of peripherally located lesions. The biopsy of lung mass located centrally requires invasive techniques like bronchoscopy; therefore, it is often omitted to preserve surgical fields and avoid invasive procedures requiring anesthesia. This poses a particular problem for carcinoid tumors as the extent of surgery and adjuvant treatment is not fully understood. The patients are at risk of getting overtreatment. The involvement of a pathologist could solve this problem. After putting the patient under anesthesia, bronchoscopy and needle biopsy of lung lesion and suspected lymph nodes should be done. The pathologist could then make frozen sections and readily analyze them to help define the extent of resection and avoid overtreatment.

Pharmacists are an essential part of the healthcare team and can assist in managing post-operative pain. They can work with the medical team to prescribe appropriate pain medication, considering individual patient factors and potential drug interactions.

Physiotherapists and pulmonary rehabilitation specialists are crucial in the post-operative care of patients who have undergone lung surgery. They can help patients with early mobilization, breathing exercises, and respiratory rehabilitation.

Guidelines issued by professional societies, such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Surgical Oncology, provide evidence-based recommendations for treating pulmonary carcinoid tumors. These guidelines are valuable resources for healthcare professionals involved in treatment planning and execution. They help ensure patients receive optimal, standardized care based on the best available evidence.

The outcome of pulmonary carcinoids is good and depends on the timely intervention. The prompt consultation with the interprofessional team improves patient recovery and survival.