Continuing Education Activity

Many medical conditions rely upon strict numerical definitions to provide a diagnosis: diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia, for example. In the case of brow ptosis, diagnosis is determined predominantly by the judgment and experience of the examining physician. Brow ptosis exists when inferior malposition of the brow interferes with aesthetics or function; therefore, the brow level deemed low in one person may be perfectly acceptable or "normal" in another. With the brow being a mobile structure and prone to the secondary effects of age, solar elastosis, muscle action, trauma, and gravity, some degree of brow descent will eventually occur in everyone. Ideal brow position is regarded differently in different genders, races, ages, and even generations. In some communities, the concept of changing the brow's position or shape is considered anathema; in many Western societies, however, it is considered routine. This activity describes the pathophysiology of brow ptosis, its presentation, and the role of mid-forehead brow lift to reverse ptosis.

Objectives:

- Describe the causes of brow ptosis.

- Review the indications for brow lifting.

- Summarize the complications of the mid-forehead brow lift procedure.

- Outline the importance of enhancing care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients who undergo mid-forehead brow lifting.

Introduction

Many medical conditions rely upon strict numerical definitions to provide a diagnosis; diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia are two examples. In the case of brow ptosis, diagnosis is determined predominantly by the judgment and experience of the examining physician. Brow ptosis exists when inferior malposition of the brow interferes with aesthetics or function. The brow level deemed low in one person may be perfectly acceptable or "normal" in another.

With the brow being a mobile structure and prone to the secondary effects of age, solar elastosis, muscle action, trauma, and gravity, some degree of brow descent will eventually occur in everyone. Ideal brow position is regarded differently in different genders, races, ages, and even generations. In some communities, the concept of changing the brow's position or shape is considered anathema; in many Western societies, however, it is considered routine.

The classic teaching describes the ideal female brow position as above the level of the bony supraorbital rim, with an upward arch such that the peak of the brow lies between the lateral limbus and the lateral canthus. In men, the eyebrows normally sit at or just above the superior orbital rim, with a flatter contour.[1] Age, cultural influences, occupations, and environmental effects all influence not only brow position and shape but also perceptions of what is aesthetically pleasing. A weather-worn farmer, for example, may have an inferiorly-positioned brow that provides some protection from light, dust, and wind. On the other hand, a model may require a higher brow position in order to appear more youthful or attractive, regardless of gender. Subtle changes in brow shape are also indicators of emotional state: low lateral eyebrows denote sadness or concern, low medial brows indicate anger, flat or low brows may display fatigue, and excessively elevated brows appear surprised. Similarly, temporal hooding and upper eyelid dermatochalasis may indicate tiredness, but when combined with frontalis overactivation because of the heavy upper eyelids, the impression of fatigue is multiplied. Finding the precise balance to portray happiness and vitality can be challenging. If upper blepharoplasty and blepharoptosis repair take place without addressing brow ptosis, the brows will appear lower after surgery because the frontalis tone is diminished once the visual fields are improved, thus also exacerbating a fatigued appearance. When brow ptosis is present, it is rarely completely symmetrical, because of myriad factors, including differences between the right and left sides of the face (hemifacial microsomia or facial paralysis), differential exposure to the elements (particularly for those who drive with a lowered window), the preferred side a patient may sleep on, and many others all affect brow position.

Common Causes of Brow Ptosis

- Aging

- Facial palsy

- Trauma

- Tumors

Clinical Presentation

- Cosmetic complaints

- Visual obstruction caused by secondary dermatochalasis and pseudoptosis

- Asymmetric brow position

- Irritation caused by secondary eyelash ptosis

In the absence of trauma, paralysis, or disease, brow ptosis occurs slowly, and most patients will not be aware of the brow ptosis until it is noted during a clinical examination or remarked upon by an acquaintance. Almost everyone over the age of 40 years, male or female, will have some degree of brow ptosis, and most of these patients will not require surgical correction.

Surgical Treatment Options

- Direct brow lift[2]

- Mid-forehead brow lift

- Pretrichial brow lift[3]

- Temporal brow lift

- Coronal brow lift

- Endoscopic brow lift[4]

- Internal (transblepharoplasty) brow lift

This article reviews the assessment and planning of brow lifts, in general, and indications and techniques for the mid-forehead lift, in particular.

Procedure History[5]

Many surgical procedures, such as cranial trephination, nasal reconstruction, and skin grafting, have been performed for hundreds of years, and some, like cataract surgery, thousands of years. Surprisingly, brow lift surgery was only reported in the 20th century when Lexer first discussed and presented the forehead lift in 1910. Subsequently, an early coronal brow lift was described by Hunt, who did not undermine any of the tissues, thus limiting results. Joseph, in 1931, presented a detailed description of the pretrichial brow lift as well as incisions made lower on the forehead to augment the brow elevation. Many surgeons continued the practice of simple tissue resection until Passot reported selective neurotomy of the frontal branch of the facial nerve in 1933. This method diminished forehead wrinkles; however, the resting tone of the frontalis muscle was lost, and this was clearly counterproductive for brow ptosis. For reasons not entirely clear, surgeons continued to explore the idea of forehead motor denervation. Edwards reported isolated temporal neurectomy as recently as 1957. A more anatomical approach was advanced by Bames that same year when he described a direct eyebrow lift. Through this approach, he weakened the corrugator muscles and undermined the forehead up to the hairline while crosshatching the frontalis muscle. Modern hairline and coronal approaches to the forehead lift and brow lift were ushered in by Pangman and Wallace in 1961. Further refinement occurred in 1962 when Gonzalez-Ulloa incorporated the forehead lift into his facelift procedure.

Despite the initial enthusiasm for coronal lifting, reports in the 1960s and 1970s suggested that results of coronal forehead lifts were short-lived, which led to the procedure losing favor. It remained unrecognized that the results were bound to be temporary without undermining after excision of excess soft tissue. Until the early 1970s, most surgical procedures consisted of resection and repair without undermining or manipulating the forehead muscles; the anatomy and physiology of the forehead had not yet been adequately appreciated.

A significant advance occurred in the mid-1970s when several surgeons (Skoog, Vinas, Hinderer, Griffiths, Marino, and others) began to manipulate the frontalis muscle, usually by excising a strip to eliminate dynamic transverse lines on the forehead. This technique also allowed better stretching of the superficial tissues. Washio was one of the first to carry out cadaver studies when he noted in 1975 that removal of a transverse section of the frontalis muscle resulted in a significant elevation of the forehead. More dramatic approaches by Tessier, LeRoux, and Jones advocated the complete removal of the frontalis muscle. Not surprisingly, this aggressively destructive approach did not endure.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the coronal brow lift became the established method of brow lifting; this was partly because of the advances made by Tessier and his group in the exposure of the skull via subperiosteal approaches. It was said, not entirely in jest, that the coronal brow lift, with its associated loss of hair and sensation, and the overly tight appearing forehead and brow was "a surgical procedure designed by men for use on women."

In the 1990s, endoscopic approaches to brow lifts were developed.[6] After the evolution of fixation techniques, it became apparent that in "brow lifting," brow shaping was at least as important, if not more so. Repositioning of the brows and forehead could be controlled with release of the periosteum from the lateral canthus to the lateral canthus across the superior orbital rims and the nasal bridge, combined with manipulation of the depressor and elevator muscles of the brows. Anatomical details were studied in order to design safe approaches that could be performed using minimal incision techniques. Understanding the sensory and motor innervation of the forehead and periorbital area allowed more accurate manipulation and modification of the tissues and permitted less invasive but also more effective techniques, such as the pretrichial and temporal brow lifts.

After some debate about the longevity and effectiveness of endoscopic brow lifts compared to coronal brow lifts, there are now two schools: one school still largely performs coronal brow lifts. However, more and more surgeons are becoming experts at performing endoscopic brow lifts. When patients are chosen correctly, these endoscopic brow lifts provide reliable and long-lasting results.[7] Coronal brow lifts, pretrichial brow lifts, mid-forehead brow lifts, direct brow lifts, and temporal brow lifts are now more often performed for specific indications. The so-called internal brow lift, or transblepharoplasty browpexy, should perhaps be called a "supporting procedure" rather than a proper "brow lift." No long-term studies show effective brow lifting, and the design of the procedure does not address the complete arch of the brow nor the forehead.

Similar to many others, the mid-forehead lift procedure has specific indications, advantages, and limitations. This approach is most useful in males with heavy brows, overactive frontalis muscles, and deep, transverse forehead wrinkles that may hide a surgical scar.

Development of Brow Ptosis

Common refrains encountered in plastic surgery are "I am becoming my mother" and "I look like my dad." The patient is saying that family characteristics, both physical structure and response to aging, are becoming apparent. Everyone has an "aging clock," which is genetically determined, but skin and deeper tissues are also affected by environmental factors such as smoking, exposure to ultraviolet light, health, and diet, among others. It can help to examine photographs of the patients when they were younger and photographs of their parents to provide patients with some context for these changes. Aging affects nearly every structure in the face, and it is certainly the most common cause of brow ptosis.

Patients routinely exposed to the elements will show marked overaction of the corrugator, procerus, and frontalis muscles, especially if they have not protected their eyes from sunlight and other harsh environmental factors. The "weathered face" seen in sailors and farmers show these changes well, not just in the region of the forehead and the brows but also in the lower face and neck. These patients develop horizontal rhytides at the root of the nose, caused by procerus muscle contraction and marked corrugator lines, which are the vertical "number elevens;" the eyebrow heads may also appear closer together because of hypertonicity of the corrugator muscles. In these cases, surgeons may make an effort to elevate and separate the brow heads - an action that would often be avoided otherwise because of the operated appearance it can produce. When brow ptosis is moderate to severe, deep horizontal forehead lines may also appear due to frontalis muscle overuse. Some patients with notable glabellar muscle hyperactivity may develop a "fat nose syndrome" caused by the downward slide of the procerus muscle and the inward movement of the corrugator muscles. This results, especially in females, in a widened root of the nose. These patients benefit significantly from disruption of the procerus and corrugator muscles during brow lifting.

It may be helpful to compare current pictures of the patient with photographs taken when the patient was younger to assess the degree to which the brow position and contour have changed. Sometimes patients are surprised to see that their brows have changed very little since their teenage years. Regardless, while young patients may look attractive with brows in either a high or a low position because many visual cues exude youth, older patients typically look better with somewhat higher brows.

Besides the glabellar impact of aging, lateral brow droop almost always progresses over time because of a lack of support from the frontalis muscle. The angle of insertion between the frontalis and the orbicularis oculi muscles becomes more acute with age, thereby leading to further loss of support laterally; this results in temporal hooding, lash ptosis, temporal brow droop, and crow's feet wrinkles.

Clinical Presentation

Presentation of brow ptosis ranges from cosmetic complaints of forehead lines and secondary heaviness, or hooding, of the upper eyelids to unattractive frown lines and problems with vision. Cosmetic patients will primarily focus on upper eyelid heaviness and fullness; other complaints may include "looking tired, angry or unhappy" either from the patient or family members and colleagues. Patients will only rarely complain that their brows are heavy or droopy in the absence of other concerns and will usually need to have brow malposition demonstrated to them in the mirror.

History

A thorough preoperative assessment is vital. Past illnesses, medications, allergies, and any history of hypertrophic or keloid scarring are noted. Specific emphasis is placed upon any history of thyroid disease, diabetes, cigarette smoking, anticoagulation use, prior eyelid or brow surgery, and any tendency to develop unusual edema. Patients with thyroid disease may have deeper frown lines and may suffer from madarosis (loss) of the brow hairs. These patients also tend to develop prolonged edema after facial surgery. Thyroid disease must be controlled and stable, ideally for at least six months, prior to scheduling surgery.

Examination of the Face

Regardless of the nature of the chief complaint, if it pertains to facial aging, a complete facial examination is critical. Patients will often present with vague concerns that relate to the appearance of aging, fatigue, or poor mood; many will ask, "what do you think?" or "what can you do for me, Doctor?" The ability to pinpoint specific problem areas and identify corresponding surgical targets is crucial; counseling patients after completing a thorough physical examination will be immensely informative for them and facilitate the development of realistic goals and expectations. As a general rule, the face should be assessed for asymmetry between the left and right sides, as hemifacial microsomia can have a profound impact on surgical outcomes, and then the proportions of the upper, middle and lower thirds of the face should be examined. Lastly, the skin color and quality of every potential cosmetic patient should be evaluated as well. This algorithmic approach to facial analysis will help prevent overlooking any major abnormalities and focus the surgeon's and patient's attention on the available treatment options, which may or may not relate directly to the chief complaint, or the patient's original self-perception.

Examination of the Brows

- Assess the hairline and forehead height relative to gender and ethnic norms.

- Assess the density and distribution of scalp hair centrally and temporally.

- Measure the height of the forehead: the distance between the corneal reflex and the anterior hairline or the distance between the central brow and the anterior hairline.

- Measure brow position: the brow can be measured relative to the superior orbital rim or measured from the lid margin to the brow or from the corneal reflex to the brow centrally and from the medial and lateral limbi to the medial and lateral brow. Others use the medial and lateral canthi as reference points and compare the left and right brow positions.

- Assess brow shape and symmetry

- Assess eyebrow hair distribution: evidence of plucking, loss, tattooing, etc.

- Assess eyebrow mobility.

- Measure the degree of true dermatochalasis, as opposed to secondary dermatochalasis caused by brow ptosis - manually lift the brow into the desired position to do this.

- Assess the medial and central superior orbital fat pads and any lacrimal gland prolapse.

- Assess the distribution and depth of the forehead and glabellar rhytides.

- Assess corrugator and procerus lines.

- Assess crow's feet.

- Evaluate for blepharoptosis.

- Assess skin thickness and quality, noting how sebaceous the glabellar skin appears.

- A basic lower eyelid assessment should be performed when considering brow or upper eyelid surgery.

When documenting brow ptosis, one reproducible measurement is the distance between the inferior limbus and the center of the brow. In most patients, this distance will be more than 22 mm. Although a measurement of less than 22 mm suggests brow ptosis, the formal diagnosis will depend upon the many other factors discussed above: age, gender, occupation, and societal expectations, among others. Ideal brow position is best determined on an individual basis by the surgeon and patient, taking into account the surgeon's experience, the patient's current and previous youthful appearance, and the specific aesthetic goals.

Measurement of Brow Ptosis

Measuring with a ruler on an upright patient, the brow is elevated medially, centrally, and laterally to assess the degree of brow ptosis. The difference between the desired brow position and the relaxed brow position indicates the degree of brow ptosis. It is critical for patients to relax the frontalis muscle before taking measurements; this may be accomplished by first having the patient close their eyes, then gently massaging the brow and forehead downward into their natural positions. From there, the patient can gently open their eyes, taking care not to engage the frontalis muscle. Occasionally, multiple attempts are required, and even with this method, reliably reproducible results can be elusive. Measurements will often reveal brow position asymmetry, and this should be indicated to the patient preoperatively using a mirror to forestall postoperative suggestions that any asymmetry is iatrogenic.

Although discussions concentrate on the brow and the brow height and contour, surgeons must not forget that the characteristics of the forehead are equally important; the severity of glabellar, corrugator, and frontalis lines, as well as skin quality should all be documented. The distance between the brow and the anterior hairline should be measured because, in some patients, hairline advancement may be desirable, which will inform the choice of brow lift approach.

Upper and lower eyelid assessment is important even for patients focused on brow lifting. The forehead, brow, and periorbital region are contiguous, and procedures performed on the brow will inevitably affect the upper eyelids, which will, in turn, influence the appearance of the lower eyelids. While some procedures directly involve both the upper and lower lids, such as canthoplasty, in many cases, the rejuvenation of the brows and upper eyelids in the absence of lower blepharoplasty will leave the inferior periorbital area looking more aged simply by contrast.

Assessment of the upper eyelids may include the following:

- Corneal reflex to lid margin distance

- Presence and position of the upper eyelid supratarsal skin crease

- Amount of tarsal platform show

- Degree of dermatochalasis: primary and secondary

- Upper eyelid fat herniation, medial and central

- Presence and degree of lacrimal gland prominence

- Upper eyelid skin quality: solar elastosis, vertical wrinkles, visible blood vessels, etc

- Bell's phenomenon

- Blink completeness

Assessment of the lower eyelids may include the following:

- Medial canthus: position, laxity, dystopia, scarring, webbing

- Lateral canthus: position, dystopia, laxity, scarring, webbing

- Lower eyelid distraction test

- Lower eyelid snapback test

- Inferior scleral show

- The prominence of medial, central, and lateral fat pads

- Nasojugal and malar groove depth

- Malar angle

- Tear film integrity and tear breakup time

- Corneal sensation and health

- Hertel measurement of the globe to assess for proptosis or enophthalmos

Anatomy and Physiology

Surface Anatomy[8]

Surgery of the brows demands a thorough understanding of surface anatomy, brow position, and brow contour. Although there is variation in brow position and shape among different ethnicities, the overall differences between males and females apply to most situations.[9] Generally, male brows are flatter, while female brows are more arched. The female brow arch is at its highest between the lateral limbus and the lateral canthus. In both genders, the medial brow ideally sits about 1 cm above the superior orbital rim. Over time, it descends more in men.

Scalp and Forehead

The five layers of the scalp are:

- Skin

- Fibrofatty superficial fascia, which is adherent to the undersurface of the skin

- Galea aponeurotica, which is contiguous with the fascia of the occipitalis and frontalis muscles

- Areolar tissue, which lies between the periosteum and the muscle/galea layer and contains emissary veins and small arteries

- Periosteum

Muscles

The eyebrow-forehead complex is composed of the following major muscles, all innervated by the facial nerve:

Occipitofrontalis[10]

Occipitofrontalis is composed of two posterior bellies, the occipitalis, and two anterior bellies, the frontalis. The galea aponeurotica or epicranial aponeurosis connects these muscles. The superior nuchal line on the occipital bone gives origin to the occipital muscle bellies. The frontalis muscle is attached to the skin and fascia of the eyebrows, passing through the orbicularis oculi muscle anteriorly; posteriorly, it becomes the galea aponeurotica and then joins with the occipitalis. The blood supply to the occipitalis comes from the occipital artery, a branch of the external carotid artery. The supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries, branches of the internal carotid via the ophthalmic artery, supply the frontalis. The frontalis muscle inserts into the eyebrow and also interdigitates with the corrugator supercilii muscles.

Orbicularis Oculi[11]

The orbicularis oculi muscle is composed of orbital and palpebral portions, with the palpebral portion further divided into preseptal and pretarsal segments. The preseptal muscle forms the lateral palpebral raphé laterally, and the pretarsal muscle fibers unite laterally at the lateral canthal tendon. The orbicularis oculi is a constrictor, causing closure of the eyelids, but it also draws in the brows, the lower part of the forehead, and the temple regions, mostly via its orbital component. The orbital orbicularis oculi is the only depressor of the brow, and sometimes a portion of it is known as the "depressor supercilii." Injections of botulinum toxin into these lateral orbital orbicularis fibers can produce a "chemical brow lift," but this technique must be performed very carefully due to the risk of blepharoptosis if the toxin contacts the levator palpebrae superioris.

Corrugator Supercilii[12]

These are responsible for producing the vertical frown lines, the "number elevens." These muscles originate from the frontal bone at the superomedial orbital rim (nasal process) and insert laterally into the medial and central third of the brow, interdigitating with the frontalis muscle. The lateral extent of the corrugator muscles varies among individual patients. Sometimes, it extends all the way to the lateral third of the brow but is often much shorter and may only reach halfway. Assessment of corrugator action is important when treating patients with botulinum toxin for cosmetic reasons or when planning surgical myomectomy as part of a brow lift.

Procerus Muscle

This muscle arises from the nasal bones and merges into the inferior part of the frontalis muscle, which lies deep to it. The procerus pulls down the medial eyebrows, resulting in horizontal nasal root wrinkles. Over time, the resulting crease can become quite deep as the central frontalis muscle descends; only by lifting the frontalis does the horizontal groove improve. This is the "fat nose syndrome" caused by a combination of medial movement of the brows because of the corrugator supercilii, inferior movement caused by the procerus, and a vertical descent of the frontalis muscle, resulting in a widening of the soft tissues at the nasal root.

The Retro-Orbicularis Oculi Fat Pad (ROOF)

Deep to the interdigitation of the orbicularis oculi and the frontalis muscles, there is a fibrofatty layer of tissue which has been called the "brow fat pad" or the retro-orbicularis oculi fat (ROOF) pad. This fibrofatty layer was described in 1909 by M. Charpy, although he mistook it to be a lateral fat pocket; in some countries, it is referred to as "Charpy's fat pad." It is distinct from the preaponeurotic fat, which lies behind the orbital septum, while the ROOF sits on the periosteum of the orbital rim and frontal bone, in front of the orbital septum, and allows the brow to glide up and down easily. In some cases, at the medial brow, the fat extends farther inferiorly below the orbital rim and into the eyelid, even as far as the inferior septal attachment to the levator aponeurosis. This fat provides the youthful fullness of the brow seen before the aging process begins and skeletonizes the brow as the fat atrophies. In general, resection of this fat should be avoided to prevent long-term cosmetic dissatisfaction.

Motor Nerves

Facial Nerve[13]

The motor innervation to the forehead, brow and periocular muscles comes from the facial nerve, which exits the skull via the stylomastoid foramen. It enters the deep posterior aspect of the parotid gland and then travels within the gland, superficial to the retromandibular vein and external carotid artery. It is typically divided into five terminal branches: frontal or temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical.

Frontal Branch of the Facial Nerve

This nerve is the most superior branch; it exits the superior part of the parotid gland and supplies the anterior and superior auricular muscles, the frontalis muscle, the orbicularis oculi muscle, and the corrugator supercilii muscles.

- The course of the frontal branch is approximated by Pitanguy's line, which starts 0.5 cm below the tragus and extends to a point 1.5 cm above the lateral brow and 2 cm lateral to the lateral orbital rim.[14]

- The nerve travels in the musculoaponeurotic layer, and superior to the zygoma, it runs on the undersurface of the temporoparietal fascia.

- The anterior branch of the superficial temporal artery and vein are lateral to the frontal branch.

- Although portrayed as a single nerve, the nerve divides into several branches over the zygomatic arch.

- Most of the nerve's branches will cross the zygomatic arch roughly 1/3 of the way from the auricle to the lateral orbital rim, but the distribution along the zygomatic arch can be broad and varied.[15][16]

- The medial corrugator and procerus muscles are innervated by the zygomatic and buccal branches of the facial nerve, which loop medially and superiorly. They also supply the medial canthal region of the medial upper and lower lids.[17]

Sensory Nerves

The three primary sensory nerves of the forehead and brow are the supraorbital nerve, the supratrochlear nerve, and the infratrochlear nerve.

The supraorbital nerve is the largest and most lateral branch of the frontal nerve, which is itself the largest branch of the ophthalmic nerve (V1). The supraorbital nerve exits the orbit either through a notch on the superior orbital rim or through a foramen just above the rim, deep to the corrugator supercilii muscle. The nerve then divides into a medial (superficial) branch, which passes over the frontalis muscle and provides sensation to the forehead skin and the anterior 3.5 cm of the scalp. A deep (lateral) branch runs between the galea aponeurotica and the periosteum towards the coronal suture. It supplies sensation to the upper eyelid, the forehead, and the scalp as far as the lambdoidal suture. This lateral division is commonly injured intraoperatively, resulting in paresthesia and scalp numbness.

- A recent study on Sri Lankan skulls found that 73.8% of supraorbital nerves exited through a notch, with the rest passing through a foramen.[18]

- 36.3% had a notch on one side and a foramen on the other side.

- 55.1% had bilateral supraorbital notches.

- 8.6% had bilateral supraorbital foramina.

- Accessory branches of the supraorbital nerve may be present in up to 20% of cases, usually exiting the skull lateral to the notch or foramen.

- The supraorbital nerve notch or foramen is typically encountered approximately 24 mm from the midline, approximately 28 mm medial to the temporal crest of the frontal bone, and approximately 29 mm from the frontozygomatic suture.

- When a foramen is present, it is located approximately 2 mm above the supraorbital margin in males and approximately 3 mm in females.

- In 80% of cases, the supraorbital foramen or notch is a few millimeters medial to the infraorbital foramen, contrary to the popular belief that both lie in the same sagittal plane.

The supratrochlear nerve may exit through a foramen, although it often exits through a notch or depression in the bone. The nerve exits lateral to the corrugator supercilii muscle's bony origin. It then enters the muscle and divides into three to four branches. After penetrating the frontalis muscle, the nerves run vertically up the scalp. The supratrochlear nerve supplies sensation to a vertical strip roughly 1 cm wide in the central forehead.

The infratrochlear nerve is a branch of the nasociliary nerve, which is a branch of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. This nerve runs along the upper border of the medial rectus muscle and will often anastomose with the supratrochlear nerve. Several branches of the infratrochlear nerve travel to the medial canthus of the eye, supplying sensation to the medial upper and lower eyelid skin, the side of the nose, the conjunctiva, the lacrimal sac, and the caruncle.

The supraorbital nerve is typically located 2.7 cm from the midline and the supratrochlear nerve 1.7 cm. There is, however, notable variability in these measurements among individuals.

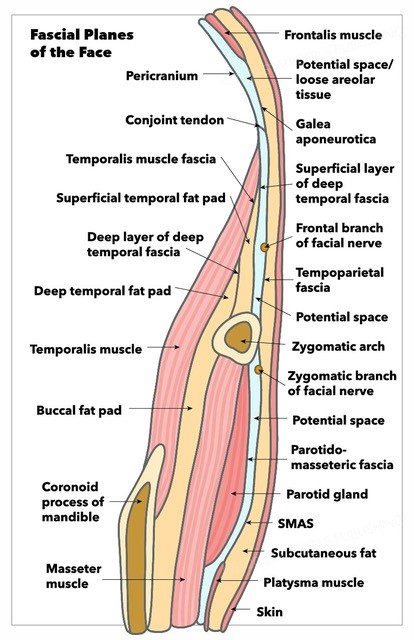

Fascia

The temporoparietal fascia is an extension of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), which extends across the zygomatic arch and, together with the galea, the frontalis, and the occipitalis forms a continuous fascial plane in the face. The temporoparietal fascia is also known as the superficial temporal fascia. The frontal branch of the facial nerve lies deep within or on the deep surface of the temporoparietal fascia.

The deep temporal fascia has superficial and deep subdivisions. The superficial temporal fascia is separated from the deep temporal fascia by loose areolar tissue, which allows easy dissection when performing a temporal dissection. This plane, also called the subaponeurotic plane, is avascular and allows quick, blunt separation.

The deep temporal fascia, or temporalis muscle fascia, is thick and overlies the temporalis muscle before splitting into two layers. Below the level of the superior orbital rim, the deep temporal fascia splits into a superficial and a deep part, separated by Yasargil's fat pad, also known as the superficial temporal fat pad (or intermediate temporal fat pad, depending on preferred nomenclature), which extends from down to the zygomatic arch.

The buccal fat pad and the deep temporal fat pad overlying the inferior part of the temporalis muscle and tendon are continuous under the zygomatic arch.

Indications

Brow lifting is helpful for patients with significant brow ptosis, which can cause visual field constriction and secondary dermatochalasis. In some patients, the brow droop may be limited to the tail of the brow, resulting in temporal hooding and eyelash ptosis. Cosmetically, brows are powerful indicators of mood, and some patients will benefit from changing the shape and curve of the brow to make the face look less tired, angry, sad, or quizzical. Patients with facial palsy may have denser brow ptosis, which also interferes with vision. Finally, some patients have undergone upper lid surgery with ptosis repair or blepharoplasty but still have underlying brow ptosis, which may be exposed or exacerbated by the lifting of the eyelids.

While mid-forehead brow lifting is not commonly performed, deep forehead lines commonly encountered in men are particularly useful for the placement of incisions comparatively close to the brows, which increases the mechanical advantage of the mid-forehead brow lift compared to endoscopic or coronal approaches. In some patients, the frontal hairline can be lowered appreciably using a mid-forehead incision and appropriate back elevation. Additionally, patients with high hairlines or baldness may not be good candidates for coronal, pretrichial, or endoscopic brow lifts because of the ensuing scars; in these cases, patients may prefer a scar in a forehead crease to scars above the brows from direct brow lifting. Many patients, particularly men, may not be bothered by the idea of a transverse forehead scar, provided it is well-hidden, but it can be challenging to avoid track marks from sutures or widening of the scar postoperatively. Having a plan for postoperative skin resurfacing and scar management may provide the patient some assurance preoperatively.

Contraindications

Mid-forehead brow lifts are carried out via incisions located in the center of the forehead. Even with the best closure, some degree of visible scarring is inevitable; patients who will not be able to tolerate this should be provided alternative options.

Absolute Contraindications

- Lack of forehead furrows: in these cases, even mild scars will be apparent

- Absolutely refusal to have a visible scar on the forehead

Relative Contraindications

- Low anterior hairline

- Female gender: there are usually better ways to address the forehead and the brow position, such as endoscopic or pretrichial approaches

- Young age in male patients, due to lack of transverse forehead rhytides

- Availability of alternative approaches that are likely to succeed with reduced scarring

- Facial paralysis: significant asymmetry in brow position may be better addressed with direct brow lifting or suture suspension techniques due to the mechanical advantage they offer by pulling directly on the brow

Equipment

Equipment required for mid-forehead brow lifting may include the following:

- Skin marker

- Local anesthetic, such as 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine

- Bard-Parker #3 scalpel handle and #15 blade

- Tissue forceps, such as Adson-Brown

- Skin hooks, such as Joseph or Senn rakes

- Dissecting scissors, such as Kaye blepharoplasty scissors

- Suture scissors, such as iris scissors

- Needle holder, such as Halsey and/or Castroviejo

- Electrocautery, either monopolar or bipolar

- Absorbable and non-absorbable suture in 5-0 and 6-0 sizes

Personnel

The mid-forehead brow lift can be performed under either local or general anesthesia, with general anesthesia more commonly used when additional procedures, such as four lid blepharoplasty, ablative LASER resurfacing, or rhytidectomy, is undertaken concurrently. In addition to a surgeon, a nurse and a surgical technologist are necessary. In the operating room, an anesthesia provider and a surgical first assistant are usually available as well.

Preparation

When performing brow lifting of any kind, it is crucial to obtain a detailed history, including determining the duration of the problem and what exactly bothers the patient. Besides the clinical examination, the surgeon should get a sense of the patient's psychological status to avoid patients who are likely to become depressed, combative, or aggressively dissatisfied postoperatively. The surgeon and patient should have a detailed discussion of the proposed surgery, addressing the anticipated outcomes and potential complications.

Patient Consultation

When assessing brows for height and shape, the patient should be sitting upright. If a patient likes how their brows, forehead, and eyelids used to look, it can be informative for the surgeon to view photographs of the patient at that age. However, care must always be taken when viewing photographs with patients or when using photograph manipulation software because doing so may lead to unreasonable expectations despite appropriate preoperative counseling. During the consultation, it is important for the surgeon not to impose their own aesthetic sensibilities upon the patient but rather provide guidance based upon experience. While the patient is holding a mirror, the surgeon should lift the brow medially, centrally, and laterally to determine the best position and arch. Doing this can also illustrate how secondary dermatochalasis of the upper eyelid is reduced and how crow's feet wrinkles are improved. Doing this also helps the surgeon estimate how much upper eyelid surgery may need to be performed along with the brow lift.

It is important to discuss surgical incisions, advantages, disadvantages, limitations, and likely scarring expected with different approaches to the operation. Before-and-after photographs of previous patients are useful in showing brow lift candidates the sort of results that are achievable and also to encourage them to ask questions based upon what they see. Photographs of scars should be shown to prospective patients as well. Standardized photographs should be taken for preoperative planning, intraoperative decision-making, and postoperative counseling. The latter is particularly useful in the event that the patient notices an imperfection after surgery - due to increased vigilance in the mirror - and the surgeon needs to assure the patient that the problem was preexisting and not a result of surgery.

Informed consent for a mid-forehead browlift should include the following points:

- The brow height and contour will not be absolutely symmetrical, as no person has perfectly symmetrical brows.

- Over the first few weeks, it is normal for the brow to settle, and therefore, the initial brow height will not be the final brow position.

- The aim is to create a natural-looking brow height and shape.

- Some degree of numbness always occurs, and in the majority of patients, it decreases over weeks but sometimes takes months.

- The brows will droop again with age and with time.

- The most significant risk is the risk of dissatisfaction with the result, but other risks include pain, bleeding, numbness, scarring, infection, and need for further surgery.

Clinical photographs are obtained from the following viewpoints:

- Full face, frontal

- Full face, 45 degrees right

- Full face, 45 degrees left

- Full face, 90 degrees right

- Full face, 90 degrees left

- Close up of both eyes, forehead, brows, and upper and lower lids at similar angles

For standardization purposes, patients should be sitting upright, with the head oriented in the Frankfort horizontal plane.

Preoperative Preparation

Forehead surgery, in general, and mid-forehead surgery, in particular, will cause impressive bruising. Therefore, aspirin and aspirin-containing products and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications are stopped one week before surgery, including most vitamins and herbal supplements. Arnica montana, however, may help to mitigate the ecchymosis. Patients must remove all makeup the night before and come in without false eyelashes. The skin is cleansed by the patient the night before and again, the morning of surgery to ensure the removal of all makeup products.

Scheduling at least two consultations before surgery allows the patient sufficient time to express desires and concerns. Furthermore, and just as importantly, it allows the surgeon to get to know the patient well. Certain patients are not suited to surgical intervention, and this may become apparent during subsequent visits. While both the patient and the surgeon must agree to proceed with an operation, either party may decide to abort the plan at any time before induction of anesthesia.

Technique or Treatment

Please see the attached composite illustration for an explanation of the following technique.

Skin Markings

- Based upon the degree of asymmetry of the brows and the configuration of the forehead furrows, the decision is made whether to use a horizontal incision across the entire forehead or to make separate incisions for each side. In the latter case, the incisions are placed in different rhytides on each side. Whenever an incision is not made all the way across the forehead, offset the incisions to avoid a visually obvious, long scar.

Anesthesia

- Supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve blocks are administered using 2% lidocaine and epinephrine mixed with sodium bicarbonate (9 to 1, respectively).

- Further injections are administered along the lines of the incision and also under the brow, and in the glabellar region. The infratrochlear nerve is blocked. Adequate vasoconstriction occurs in 10 to 15 minutes, and cool compresses are applied at this stage and continued throughout the procedure to minimize ecchymosis and edema.

- The local anesthetic injections are administered before the preparation and draping of the patient, allowing time for anesthesia and vasoconstriction to occur.

Incisions

- A No. 15 blade is used to make a skin incision down to the galea aponeurotica.

- Incisions carried laterally to the temporal line of fusion must be skin deep only.

Dissection

- The plane of dissection is subcutaneous, similar to a direct brow lift, and the galea/frontalis muscle is not violated. Elevating the inferior flap with rakes and performing a combination of sharp dissection and blunt separation with scissors is the most common approach.

- There is a loose subcutaneous aponeurotic layer; dissection is performed in this layer all the way to the superior orbital rims.

- The corrugator and procerus muscles are accessed by incising the galea horizontally about 3 cm above the nasal root and carrying the dissection deeply. Care is taken not to injure the supraorbital nerves laterally.

- The degree to which the corrugator and procerus muscles need to be weakened is based on preoperative assessment. In some patients, partial removal of the muscles with clamping and cauterization is performed. In others, surgeons aim for minimal weakening. For more aggressive weakening, the muscles can be disinserted from their bony origins while protecting the neurovascular bundles.

- Some surgeons transfer fat from the eyelids or elsewhere in the face to the area where the procerus and corrugator muscles are removed for two reasons: (1) to fill any hollows that may form and (2) to fill the preoperative glabellar rhytides.

- Because the orbital orbicularis oculi is a depressor of the brow, in some patients, surgeons weaken the depressor supercilii muscle.

- The forehead above the incision is undermined for approximately 1 cm to facilitate a tension-free closure and wound edge eversion. Should the hairline require advancement, additional undermining will be necessary. Deep forehead rhytides require partial-thickness horizontal incisions of the frontalis muscle for effective rejuvenation.

- The skin inferior to the incision is retracted superiorly until the brow is just past its ideal position and the redundant skin is excised; some degree of overcorrection is required to account for early settling of the brow, though not enough to create a surprising appearance. The subdermal layer is then closed with 4-0 polydioxanone sutures.

- Some surgeons run horizontal and vertical mattress sutures from the point of the incision to the orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi, which provides frontalis tightening and support, and reduces the tension placed on the skin closure. This approach is especially effective in males with significant ptosis of the brows.

- The dermis is sutured with 5-0 polydioxanone, and skin closure is achieved with a 6-0 polypropylene suture.

- Steristrips and a soft pad are applied. An additional pressure dressing can help minimize bruising and swelling, but care should be taken to ensure that it is neither too tight nor that it applies downward tension on the brows.

Postoperative Care

The dressing is removed the day after surgery, and wound closure strips and sutures are removed after seven days. More wound closure strips or skin glue can be placed if needed. Overcorrection of the brows is to be expected for the first few weeks. The forehead and the brows always settle by at least 25%. However, since the incision is closer to the brow than with the coronal or endoscopic brow lifts, early brow descent after surgery is less dramatic with mid-forehead lifting. Surgeons should obtain clinical photographs at two months and six months after surgery and observe patients for up to a year.

Complications

Hematoma

Like the rest of the face, the forehead has an excellent blood supply, which contributes to rapid healing and low rates of infection. The corollary is that mid-forehead brow lifting tends to be relatively bloody. Meticulous hemostasis is crucial during and after the dissection. A hematoma encountered postoperatively requires immediate drainage because of the risk of skin flap necrosis and stretching of the forehead skin, which can negate the effect of the brow lift.

Facial Nerve Injury

The frontal branch of the facial nerve is at risk if the lateral end of the incision is extended and carried deeper than the skin.[19] Local edema and tension can give rise to paresis, which will recover. Electrocautery should also be applied very sparingly, if at all, in the area of the nerve; hemostasis with pressure and/or a thrombin product is preferable.

Sensory Nerve Injury

- Hypesthesia/paresthesia: most patients experience temporary hypesthesia because of the raising of the skin flap; this usually recovers in a few weeks. If the supraorbital and/or supratrochlear nerves are injured, long-term or permanent numbness can ensue.

- Neuralgia: injury to the supraorbital nerves can cause neuralgia in rare cases.

Incision Pruritus

This is common for the first one to two weeks after surgery.

Unsightly Scar

The final appearance of the forehead scar is very difficult to predict, even when the incision is closed with attention to eversion and minimization of tension. Patients with significant sun damage or darker skin are likely to suffer hypo- or hyperpigmentation, but a widening of the scar is typically the most troublesome outcome. Skin resurfacing or the use of silicone gel can improve the appearance of the postoperative scar substantially; some surgeons will address scars with aggressive prophylaxis; however, planning laser resurfacing as soon as the sutures are removed and insisting that patients avoid sunlight exposure for an entire year after surgery. Numerous laser options are available: Er:YAG and CO2 for resurfacing, PDL and Nd:YAG for telangiectasias, and Er:glass for depressed scars.

Brow Asymmetry

Brows are, by their very nature, almost always somewhat asymmetric. Postoperative asymmetry should ideally not be more than that seen preoperatively. Most bystanders will not notice a brow asymmetry of less than 3 mm.[20]

Abnormal Soft Tissue Contours

Contour deformities are not uncommon after resection of the corrugator and procerus muscles. Conservative myomectomy rather than the extirpation of the muscles leads to fewer contour deformities. Fat grafting to fill any volume deficits at the conclusion of surgery can be very helpful for improving patient satisfaction.

Lagophthalmos

Brow lifts are often combined with upper eyelid surgery. Temporary lagophthalmos is very common but should only last for a few days. Patients noted to have xerophthalmia, lagophthalmos, or a poor Bell's phenomenon preoperatively may require a more conservative surgery or staging between a brow lift and upper blepharoplasty. In most cases, the brow lift should be performed first so that the surgeon can assess how much dermatochalasis remains before excising the upper eyelid skin. While some surgeons do successfully perform the blepharoplasty before the brow lift, there is the risk that an aggressive brow lift performed after the blepharoplasty will result in significant lagophthalmos.

Clinical Significance

Mid-forehead brow lifts were more popular before small incision procedures, and endoscopic procedures were developed, and they have become today's gold standard. However, there are specific patients for whom the mid-forehead brow lift is ideal: typically men with thinning or absent hair, deep forehead rhytides, and sparse eyebrow hair. When patients are chosen with care, the outcomes are satisfying and cosmetically very acceptable. The main advantage of the mid-forehead brow lift is greater mechanical advantage than with coronal and endoscopic lifts due to the proximity of the dissection to the brow itself; thus, brow height and contour can be manipulated more effectively and more reliably. Asymmetry is also addressable with greater ease using mid-forehead, direct, and suture suspension techniques compared to coronal and endoscopic approaches. Lastly, the mid-forehead brow lift technique is simple and can be performed easily in the office on an outpatient basis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Mid-forehead brow lifts are ideally performed by experienced and skilled surgeons with intimate knowledge of the relevant anatomy and physiology and familiarity with preoperative and postoperative care of brow lift patients. A team experienced in managing periocular and aging face issues is indispensable when caring for brow lift patients, as preoperative visual assessment, preoperative photography, and postoperative suture removal are often performed by personnel other than the operating surgeon.[21] [Level 5]