Continuing Education Activity

Bronchiectasis is a chronic lung disease characterized by persistent and lifelong widening of the bronchial airways and weakening of the function mucociliary transport mechanism owing to repeated infection contributing to bacterial invasion and mucus pooling throughout the bronchial tree. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of bronchiectasis and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of bronchiectasis.

- Summarize the role of airway obstruction, infection, and peribronchial fibrosis in the pathophysiology of bronchiectasis.

- Outline the evaluation of bronchiectasis.

- Review the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients with this condition.

Introduction

Initially, bronchiectasis was described in the early 19th century by Laennec. Bronchiectasis is a chronic lung disease characterized by persistent and lifelong widening of the bronchial airways and weakening of the function mucociliary transport mechanism owing to repeated infection contributing to bacterial invasion and mucus pooling throughout the bronchial tree.[1][2][3] Bronchiectasis is responsible for the significant loss of lung function and one that can result in considerable morbidity and even early mortality.

Etiology

Historically, the most common cause of bronchiectasis was thought to be an antecedent respiratory infection, often during childhood. The causes are idiopathic, acquired, or infection-related.

Bacterial Infections

- Mycobacterium: Tuberculosis and atypical

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Mycoplasma and HIV

Viral Infections

- Respiratory syncytial virus and measles

Fungal Infections

Bronchial obstruction

- Foreign body

- Mucus plug

- Tumors

- Hilar lymphadenopathy (right middle lobe syndrome: extrinsic compression from postinfectious adenopathy)

Postinflammatory pneumonitis

- Chronic aspiration/gastroesophageal reflux disorder

- Chronic sinusitis

- Inhalational injury

Congenital/Genetic

- Cystic fibrosis

- Young syndrome

- PCD: primary ciliary dyskinesia (Kartenger Syndrome)

- immunodeficiency (hypogammaglobulinemia)

- Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency (AAT)

- Mounier-Kuhn syndrome

Inflammatory diseases

- Ulcerative colitis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Sjögren syndrome

Pulmonary Diseases

- Asthma

- Bronchomalacia

- Cronic-obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (reported in up to 50% of patients with moderate-to-severe COPD)

- Diffuse panbronchiolitis

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (traction bronchiectasis)

Altered immune response

- Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Others

- Yellow nail syndrome (yellow nails, lymphedema, pleural effusion, bronchiectasis 40% first described in 1964)

Epidemiology

Bronchiectasis predominance is not clearly understood. Global statistics suggest that the incidence of bronchiectasis has risen over the past few years. It can exist in any age group. However, it generally occurred in childhood during the pre-antibiotic period.[4] Recent evidence shows that bronchiectasis disproportionately affects women and older individuals, and may be contributing to an increasing healthcare burden.

Pathophysiology

The three most important mechanisms that contribute to the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis are recurrent infections, airway obstruction, and peribronchial fibrosis.

Neutrophils dominate airway inflammation in bronchiectasis, driven by high concentrations of neutrophil chemoattractants such as interleukin-8 (CXCL-8), and leukotriene B4. Airway bacterial colonization occurs because of impaired mucociliary clearance and because of the failure of neutrophil opsonophagocytic killing. Other mechanisms of immune dysfunction include the inability to clear apoptotic cells and invasion of T-cells, with recent reports leading to Th17 cells playing a significant role. Histologic changes in bronchiectasis include cartilage destruction and fibrosis, mucosal and mucous gland hyperplasia, inflammatory cell infiltration, and increased mucous and exudate.

History and Physical

History of a long-standing cough with purulence is typical of bronchiectasis. Patients may report repetitive pulmonary infections that require antibiotics over several years. Patients can also present with progressive dyspnea, intermittent wheezing, hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain, and associated fatigue and weight loss. The hemoptysis is mild and manifested by blood flecks in the patient's usual purulent sputum, which is occasionally life-threatening. Often patients are diagnosed after many years of symptoms when a chronic cough or hemoptysis becomes debilitating.

Cough: 98%, sputum: 78% (sputum is typically mucoid and relatively odorless), dyspnea: 62%, haemoptysis: 56% to 92%, and pleuritic chest pain: 20% (secondary to chronic coughing).

Physical: Findings are nonspecific.

General findings may include digital clubbing (2% to 3%), cyanosis, plethora, wasting, and weight loss.

- Local chest examination: Most commonly crackles and wheezes on auscultation.

- Crackles: 75%, usually bi-basal.

- Wheezing: 22% (wheezing may be due to airflow obstruction from secretions)

Clinical Features of Associated Causative condition:

- Connective tissue diseases: Arthritis Sicca syndrome

- ABPA: Prominent wheezing

- Bronchial obstruction: localized wheezing

- PCD, CF, Young Syndrome: Recurrent sinus disease, infertility

- Features of acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis: Change in sputum production, increased dyspnea, increased cough, fever, increased wheezing, and reduced pulmonary function.

Evaluation

The recommendations of the British Thoracic Society (BTS) suggest checking for underlying factors involving immunoglobulin tests (IgA, IgM, IgG, and IgE), and testing to exclude ABPA (specific IgE to Aspergillus, IgG to Aspergillus, and eosinophil count).[5][6][7][8] Sputum culture to exclude nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) and assessment of autoantibodies are also suggested. Testing for cystic fibrosis (CF) (sweat test and/or screening for common CF mutations) is recommended for patients aged younger than 40 years or with recurrent Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus isolation, or upper lobe predominant disease irrespective of age.

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin level, Ciliary function analysis, and Serology for HIV if indicated.

Imaging:

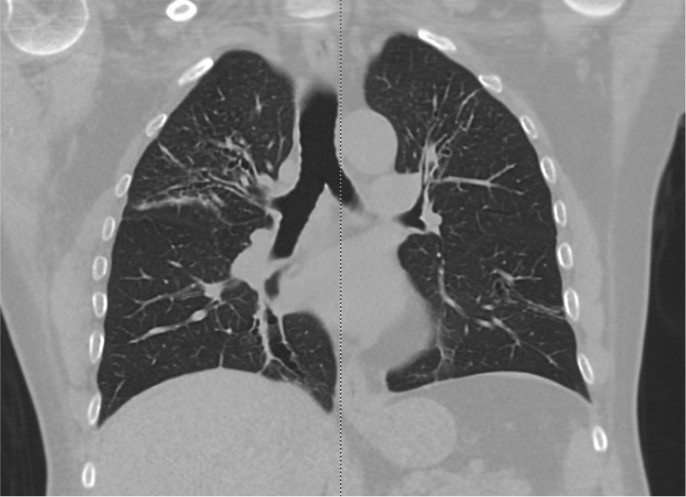

Chest radiography is usually the initial study performed in suspected bronchiectasis.

Signs on chest x-ray include the identification of parallel linear densities, tram-track opacities, or ring shadows reflecting thickened and abnormally dilated bronchial walls.

Signs of complications/exacerbations, such as patchy densities due to mucoid impaction (mucus may become of high density due to chronic inspissation) and consolidation, volume loss secondary to mucoid bronchial obstruction or chronic cicatrization are also seen.

In comparison to chest x-ray, CT is both more sensitive and provides more specific information. In addition to making the diagnosis, the pattern of disease on HRCT may enable one to limit the differential to a single/few specific causative entities.

The CT chest signs of bronchiectasis were first described by NAIDICH et al. in 1982. Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is preferred over high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) as it can obtain thin sections of 1 mm (high resolution). HRCT is performed when MDCT is not available.

Bronchial dilation, the cardinal sign of bronchiectasis, is characterized:

- A broncho arterial ratio (BAR) of more than 1

- Lack of bronchial tapering (normal airways diminish in caliber as they extend toward the lung periphery)

- Visibility of airways within 1 cm of the pleural surface (normal airways should not be visualized this far out in the lung periphery) or abutting the mediastinal pleural surface.

Usual Pattern on CT scan of the Chest

Cylindrical (tram track sign): Dilated airways seen in a horizontal orientation.

Signet-ring: The dilated airway lies adjacent to a pulmonary artery branch giving the appearance of a ring (internal bronchial diameter greater than that of the adjacent pulmonary artery).

Varicose: Implies non-uniform bronchial dilatation. The bronchi resemble varicose veins. The luminal dilatation is characterized by alternating areas of luminal dilatation and constriction, creating a beaded appearance, and the wall thickening is irregular. This varicose bronchiectasis serves as an intermediate step before the development of grossly dilated cystic airways.

Cystic or saccular: A cluster of thin-walled cystic spaces.

Mosaic lung attenuation: The terminology is used to characterize heterogeneous lung density in the damaged lung segments owing to air trapping and hence has a geographic distribution. On expiration, this result can be produced or exaggerated.

Dilated bronchial arteries: These are best-demonstrated post administration of intravenous contrast. These tortuous vessels extend along the central airways toward the hila. It is these vessels that are often responsible for hemoptysis.

Other Findings:

Lobar collapse

Mycetoma formation (Fungus ball): Aspergillus fumigatus (a fungus) may colonize dilated airways or bullae/cavities. It is a major source of hemoptysis.

Decreased Lung function:

Airflow obstruction: FEV1 decreased

Air trapping: Residual volume increased

Treatment / Management

Bronchiectasis is treatable but rarely curable.

Treatment Goals:

- Identifying and treating the underlying cause

- Improve tracheobronchial clearance

- Control infection

- Reverse airflow obstruction

General Management

1. Identifying and treating the underlying cause: Immunoglobulin replacement, steroids, antifungals for ABPA, treatment for NTM, and CF all represent opportunities to treat the underlying cause specifically, and systematic testing of all patients is recommended in consensus guidelines.[9][10][11]

2. Improve tracheobronchial clearance: Most physicians recommend mucus clearance as the mainstay of therapy in bronchiectasis, Postural drainage consists of adopting a position in which the uppermost lobe is drained, and should be performed for a minimum of 5 to 10 minutes twice a day. Efficiently performed, this is of great value both in reducing the amount of cough and sputum and in preventing recurrent episodes of bronchopulmonary infection.

Deep breathing followed by forced expiratory maneuvers (the "active cycle of breathing" technique) is of help in allowing secretions in the dilated bronchi to gravitate towards the trachea, from which vigorous coughing can clear them. "Percussion" of the chest wall with cupped hands may help to dislodge sputum, and a number of mechanical devices are available, which cause the chest wall to oscillate, thus achieving the same effect.

3. Control infection: The choice of antibiotic should primarily be based on the results of culture and sensitivity. When no specific pathogen is identified, and the patient is not seriously ill, an oral agent like amoxicillin, co-amoxiclav, or macrolides for 2 weeks is sufficient.

Use a higher dose of oral amoxicillin 1 gm twice per day for 2 weeks, especially if colonized with H. influenza. If pseudomonas-colonized, then a 2-week course of ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice per day (with cautious use in the elderly) is reasonable.

For patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms, parenteral antibiotics, such as an aminoglycoside (gentamicin, tobramycin), antipseudomonal synthetic penicillin, a third-generation cephalosporin, or a fluoroquinolone, may be indicated.

Treatment for Pseudomonas isolates 2 weeks of intravenous (IV) antipseudomonal antibiotics, nebulized colistin for 3 months, or nebulized colistin for 3 months with an additional 4 weeks of oral ciprofloxacin.

Maintenance therapy with intermittent antibiotics is not used routinely in patients with non-CF bronchiectasis, and the decision to use long-term antibiotics should be individualized.

Inhaled aminoglycosides can be of benefit in chronic non-CF bronchiectasis; however, the treatment needs to be of sustained duration.

4. Control reverse airflow obstruction: In patients with airflow obstruction, inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids should be used to enhance airway patency.

5. Lifestyle modifications: As with other respiratory diseases, patients with bronchiectasis should be encouraged to stop smoking. Vaccination against influenza and pneumococcal disease is also recommended.

Adjunctive Surgical Treatment:

-

Surgery is only indicated in a small proportion of cases. These are usually young patients in whom the bronchiectasis is unilateral and confined to a single lobe or segment, as demonstrated by CT.

-

Surgery is an important adjunct to therapy in some patients with advanced or complicated disease.

- Single- or double-lung transplantation has been used as a treatment of severe bronchiectasis, predominantly when related to CF. In general, consider patients with CF and bronchiectasis for lung transplantation when FEV falls below 30% of the predicted value. Female patients and younger patients may need to be considered sooner.

-

Massive hemoptysis: Bronchial artery embolization and/or surgery is first-line therapy for the management of massive hemoptysis.

Differential Diagnosis

- Alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency

- Aspiration pneumonitis and pneumonia

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary lung disease

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Pearls and Other Issues

Bronchiectasis complications include pneumonia, lung abscess, empyema, septicemia, cor pulmonale, respiratory failure, secondary amyloidosis with nephrotic syndrome, and recurrent pleurisy.

Prognosis

The disease is progressive when associated with ciliary dysfunction and cystic fibrosis, and eventually causes respiratory failure in other patients. The prognosis can be relatively good if postural drainage is performed regularly, and antibiotics are used judiciously.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bronchiectasis is a progressive disorder with no cure. Hence it is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the primary care physician, nurse practitioner, pulmonologist, infectious disease expert, thoracic surgery, and an internist. The key is to improve symptoms and prevent relapses.[12][13] These patients often develop respiratory infections that require antibiotics. At some point, most patients develop complications that include pneumonia, lung abscess, empyema, septicemia, cor pulmonale, respiratory failure, secondary amyloidosis with nephrotic syndrome, and recurrent pleurisy.

The disease is progressive when associated with ciliary dysfunction and cystic fibrosis and eventually causes respiratory failure. In other patients, the prognosis can be relatively good if postural drainage is performed regularly, and antibiotics are used judiciously.[7]