Continuing Education Activity

Breast masses are common and are associated with a wide spectrum of diseases, from benign physiological adenosis to advanced malignancy. To assess patients presenting with a new breast mass, a structured and comprehensive approach is required. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of a new breast mass and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the common causes of a new breast mass.

Assess the physical examination findings associated with a new breast mass.

Evaluate the common and novel genomic investigations for patients with a new breast mass.

Communicate the management considerations for patients with a new breast mass.

Introduction

Breast lumps or masses are very common, particularly among women of reproductive age. Over 25% of women are affected by breast disease in their lifetime, and the vast majority of these cases present initially as a new breast mass in the primary care setting. Breast masses have a wide range of causes, from physiological adenosis to highly aggressive malignancy. Although the majority of breast masses are present in adult women, children and men can also be affected. Indeed, male breast cancer is a well-documented condition and requires a considered index of suspicion for its timely diagnosis and intervention.[1][2]

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer in women worldwide, with an incidence of approximately 12%, and therefore. However, the vast majority of breast lumps are benign. A thorough and structured approach is required in all cases. The approach should generally follow the triple-assessment pathway of clinical examination, radiological imaging, and pathology analysis. Such an approach is described in this topic, with examples throughout of the common breast pathologies encountered.[3][4]

Etiology

Anatomy

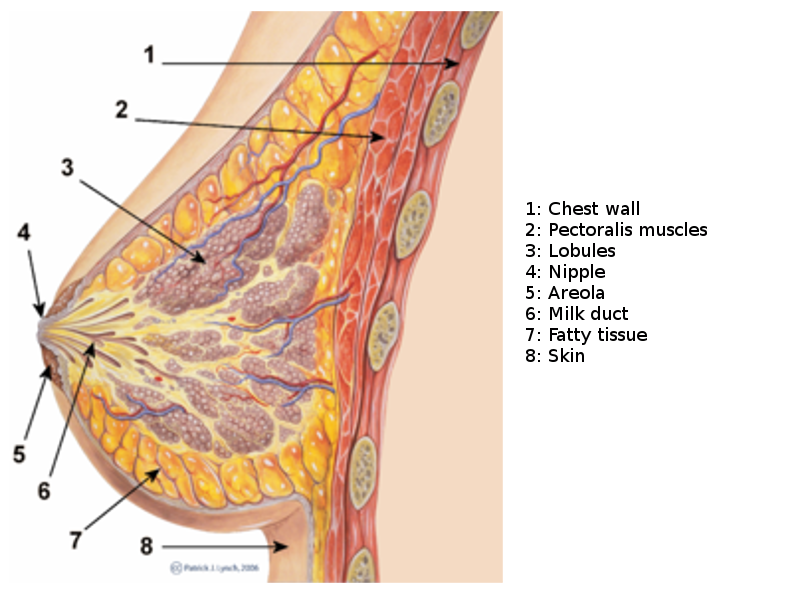

The breast, or mammary gland, is a modified sweat gland containing various fibrous, glandular, and adipose tissue. Each breast has 15 to 20 lobes drained by lactiferous ducts that converge beneath the nipple in the subareolar region. The lobes are supported by fibrous stroma and fatty stroma. Lymphatic drainage is primarily through the axillary lymph nodes and involves the pectoral, subscapular, and internal mammary nodes.[5] See Image. Breast Sagittal View. Breast tissue is present in children and males but is more developed in females of reproductive age due to hormonal surges that arise at puberty. Breast tissues involute significantly following menopause; the glandular tissue atrophies due to reduced circulating estrogen levels and is largely replaced by fatty tissue. Breast tissues and most breast pathologies are responsive to changes in hormone levels.[5]

Risk Factors

The primary risk factor for developing breast cancer is excess exposure to estrogens. Therefore, it is essential to interrogate lifetime estrogen exposure in all patients presenting a new breast mass. Early age of menarche, late age of first pregnancy, nulliparity, oral contraceptive or hormone replacement therapy, and late menopause increase estrogen exposure, while breastfeeding is a protective factor.[6] Male patients should be asked about previous hormonal treatments for prostate cancer, the use of finasteride or testosterone, episodes of orchitis/epididymitis, or previously diagnosed Klinefelter syndrome.[7] Other risk factors, such as excess alcohol intake and obesity, are thought to increase endogenous estrogens.[8]

Epidemiology

According to the WHO, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with an estimated lifetime risk of 12%.[3] Benign breast disease is often more common, affecting between 25% and 50% of adult women and accounting for 3% of general practitioners' encounters with female patients.[9] A majority of these cases may present initially with a new breast mass. Therefore, every clinician must have confidence in assessing and managing these patients, and a thorough, consistent approach enables this. The triple assessment approach discussed in this topic has improved outcomes by allowing timely diagnosis and a coordinated interprofessional approach.[10]

Pathophysiology

Breast cancer, the most common cancer-related causality of mortality, is a complex, heterogeneous disease classified into 3 main categories: hormone-receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 overexpressing, and triple-negative breast cancer. The mentioned classification is based on histopathological findings. The discrete identification of the breast mass is helpful for further target therapy. Accordingly, tamoxifen and trastuzumab would benefit estrogen-receptor-positive and HER-2-positive breast cancers, respectively.[11]

History and Physical

A thorough and accurate history is the cornerstone of approaching any new breast mass.[12] Particular emphasis should be placed on the chronological development of the lump and its symptoms.

Timing

It is not always possible to establish the duration for which the mass has been present. Patients who do not regularly perform breast self-examination may take longer to notice a breast lump. Indeed, a proportion of breast lumps are identified through routine screening, so this is not necessarily an accurate way of determining the acuity of such a mass.[7] More importantly, it is important to establish whether the mass has developed in association with trauma or other symptoms and how rapidly the mass appears to be growing or changing.

Associated Symptoms

Localized

An acutely tender breast lump is more likely to be an abscess or hematoma secondary to trauma. Cancerous breast masses rarely present with pain, although the presence of pain should not exclude neoplastic lesions from the differential. Nipple changes or discharge merits attention, as these can correlate with some less common breast tumors, as well as changes to the overlying skin, including ulceration, eczema, or tethering.[13][6]

Systemic

As with every new patient assessment, a careful systems review should seek evidence of disseminated disease. History of weight loss, dyspnoea, and bone pain are important in highlighting potential sites of metastasis.[14]

Family History

Family history would be 1 of the key risk factors for breast cancer, particularly if family members were less than 50) at the age of diagnosis. Establishing an accurate family history is crucial, and it should also include relatives diagnosed with non-breast cancers, especially if at a young age. Detailed family history can be instrumental in generating an accurate risk profile.[15]

Medical History

A detailed understanding of the patient's medical history and medications is crucial in the initial work-up of any new patient. A patient taking oral contraceptive medication, hormone replacement therapy, corticosteroids, or other steroid medication such as spironolactone must understand these implications, and a medication review may be necessary before carrying out further investigations.[6] For a patient presenting with a breast mass and highly suspicious of breast cancer, based on history, physical examination, and tissue diagnosis, several further evaluations are indicated to assess the disease burden. These step-wise diagnostic approaches include systematic lung, bone, and liver evaluations with chest X-rays, bone scans, liver ultrasonography, and abdominal CT scans. However, the mentioned diagnostic approaches should be limited to patients with a moderate to high risk of cancer metastasis. Accordingly, performing these evaluations in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast would not be recommended.

Triple Assessment

Physical Examination

Clinical examination of a breast lump is the first stage in the triple-assessment approach. Both breasts and axillae should be examined meticulously by the clinician, and a physical examination of other body systems should be carried out as indicated by the history. Although it can be tempting to bypass the physical examination in favor of other, more targeted investigation modalities such as mammography or sonography, the findings of the physical examination are crucial for the effective diagnosis and management of breast disease.[16] Repeated studies have indicated that optimal sensitivity and specificity can be achieved only by combining all 3 assessments.[4][16]

Clinical breast examination is often conducted with a chaperone to make the patient feel more comfortable. The entire chest and abdomen should be exposed. Each breast and axilla should undergo a visual inspection, looking for skin changes, nipple discharge, visible masses or asymmetry, and tethering to underlying structure; this feature can be exaggerated by asking the patient to place their hands on their hips and lift the arms.[17] The breasts can most easily be palpated by asking the patient to lie back at approximately 30 degrees and rest their palm up underneath their head. Palpation of the breast must proceed in a structured manner; generally, clinicians use a 4-quadrant approach (upper outer, upper inner, lower outer, and lower inner quadrants), followed by palpating the areola and the axillary tail. Particular attention should be paid to the inframammary fold and the axillary tail. The normal breast is examined first, and the tissue is assessed for consistency. Masses are most often detected in the upper outer quadrant, as most breast tissue is located here.

Palpable breast masses should be described in location, size, shape, tenderness, fluctuance, mobility, texture, and pulsatility. If the patient describes nipple discharge that is not immediately visualized, it is appropriate to ask the patient to express the discharge themselves before the clinician attempts to do so.[18] Following palpation of the breast, the clinician must always palpate the axilla and supraclavicular region for lymphadenopathy. This area may present with enlarged, tender, or firm nodes, the number and nature of which should be documented. During the examination of the axilla, the clinician should take the weight of the patient's arm to relax the pectoralis muscles.[19]

Evaluation

Radiological Assessment

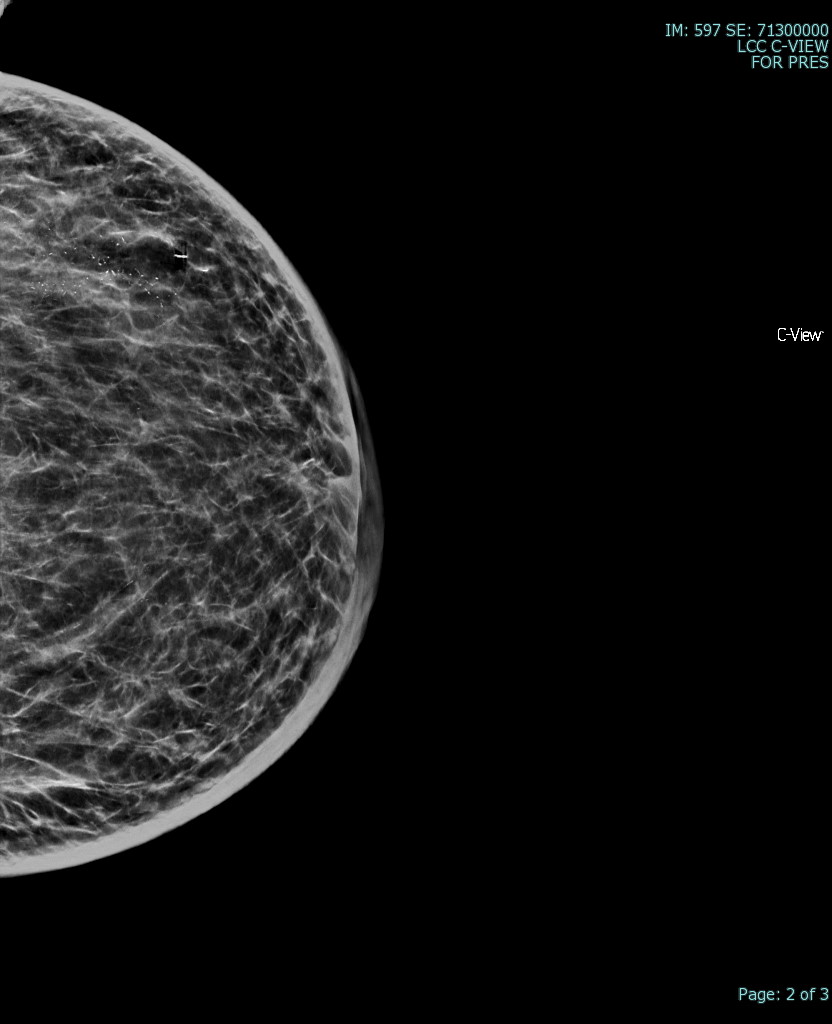

The most common radiological tools for imaging breast tissue are mammography, ultrasound, and MRI (see image. Superficial Vein With an Area of Intraluminal Thrombus, Ultrasound). Mammography is the first-line imaging for women over 35 who present with a new breast mass. Mammography is also helpful in screening asymptomatic women who fit their regional screening criteria. This process involves obtaining X-ray imaging in a craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique plane to ensure imaging of all breast tissue. Mammography tends to have higher specificity and lower sensitivity than ultrasound.[20] Mammography can have negative findings in up to 15% of patients with breast cancer.[21] See Image. Breast Mammogram.

Ultrasound imaging is preferred to mammography in younger women and men as their breast tissue tends to be denser, with a much lower proportion of fatty tissue. This dense tissue impedes the accuracy of mammography and makes it more challenging to detect microcalcifications.[20] MRI can also be useful in the assessment of a new breast lump. It is not routinely used as it is more expensive and has longer wait times, but it shows high sensitivity for detecting and delineating breast masses. It is the preferred modality for patients with previous breast augmentation surgery, as the breast implants can distort the underlying parenchyma in mammography or ultrasound. It may also be recommended for high-risk patients, such as those with known underlying BRCA mutations.[22]

Imaging reports are standardized using BI-RADS – Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (fifth edition). This standard allows breast imaging to be described according to a certain structure: density of breast tissue, presence and location of a mass or masses, calcifications, asymmetry, and any associated features.[23] This classification system divides patients into categories 0 to 6, depending on the likelihood of malignancy in the obtained images:

- BI-RADS 0 – insufficient or incomplete study

- BI-RADS 1 – normal study

- BI-RADS 2 – benign features

- BI-RADS 3 – probably benign (<2% risk of malignancy)

- BI-RADS 4 – suspicious features (divided into categories 4a, 4b, and 4c depending on the likelihood of malignancy)

- BI-RADS 5 – probably malignant (>95% chance of malignancy)

- BI-RADS 6 – malignant (proven malignant on tissue biopsy)

The BIRADS system includes different mass classifications depending on the imaging modality. In mammography, to be considered a mass, the lesion must be visible in 2 different projections, have convex outer borders, and be denser in the center than on the periphery.[24] In ultrasound, a mass requires visualization in 2 different planes. Masses are defined according to their shape, margin, and density. In terms of shape, a mass can be categorized as round, oval, or irregular. Circumscribed margins are more apt to be benign, whereas microlobulated, indistinct, or spiculated margins are more likely malignant. The margin may also appear obscured. Mass density is compared to surrounding normal tissues - higher, equal, or lower - or may reflect fat within the mass.[23]

Pathology Analysis

The third aspect of triple assessment requires an invasive procedure to allow pathological diagnosis. Pathology analysis involves either fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or core biopsy.[4] Cytology allows an analysis of cells in isolation, while histological examination of a biopsy can provide more detail about the architecture of tissues. These invasive procedures involve risks to the patient and should, therefore, only occur when the index of suspicion is present. Whether to perform FNAC or core biopsy depends on several factors, including the expertise of the clinician, available diagnostic equipment, and the site of the lesion. However, FNAC is generally preferred as the first line since it is less invasive.[25]

The need for pathological analysis has undergone review. It is thought unnecessary in some instances if the physical examination and radiological assessments are negative in a patient of low risk (ie, young patients under the age of 25).[26] The decision to proceed with FNAC or core biopsy is a clinical one, but in all cases, it should not be undertaken without due consideration of the risk-benefit analysis. It is suggested that a minimum of 6 epithelial cell clusters may provide a reasonable balance to reduce false-negative FNAC smears and an inappropriate rate of inadequate smears. The lesion, which is well-circumscribed and mobile with a typical catch-a-mouse appearance, is characteristic of a fibroadenoma.

The histological diagnostic features of fibroadenoma can be described as sheets of uniformly distributed epithelial cells typically arranged in a honeycomb pattern. Foam and apocrine cells are present, and excessive mitotic activity or anaplasia is absent. Cytopathologic features of fibroadenoma include hypercellularity with characteristic monolayer “staghorn” sheets of benign-featured epithelial cells mixed with myoepithelial cells. The sheets have an antler-like configuration on their edges. Moreover, the background of the aspirate is composed of numerous bipolar nuclei.

Depending on the likely differential and the level of resources available, many other investigations can be carried out when analyzing breast masses. Baseline blood tests are usually recommended in patients likely to undergo surgery, emphasizing hemoglobin, bone profile, and liver function tests in case of suspected hepatic metastasis. Inflammatory markers and blood cultures should be considered where a breast abscess is suspected. Tumor markers such as Ca27.29 and Ca15-3 can be used for prognostication and monitoring for recurrence. Nuclear medicine, PET scanning, and bone isotope scanning may help to assess metastatic disease. For example, genome mapping may be an option if a patient is suspected of carrying the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene.[6]

The utilization of biological markers to provide details about clinical characteristics has been considered a well-established part of a newly diagnosed breast mass that can give information on prognosis independent of other findings. The resultant information would assist in patient risk stratification within predetermined clinical classifications and further identify a sub-group of patients who would benefit most from adjuvant therapy. An optimal prognostic marker, with the specific capability to predict the relapse risk, would assist a precise patient selection among those with node-negative breast cancer to be offered adjuvant therapy.

Several alternative prognostic markers have been tested to optimize a clinically relevant marker in a newly diagnosed breast mass. Accordingly, the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines have approved the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay level of uPA/PAI-1 as a prognostic marker in a newly diagnosed breast cancer with a couple of significant indexes, including lack of lymph node involvement and hormone-receptor positivity. However, the use of other biological markers of tumoral proliferation and/or tumor suppressors, including Ki-67 and P53, in the management process of the breast mass has not been well-established yet.[26][27]

Evaluating predictive markers, with the advantage of providing a certain beneficial target treatment modality, has been an area of research interest in breast cancer. Including a couple of well-studied markers, estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2, in the routine evaluation of a newly diagnosed breast cancer has been recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines. The estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 positive breast cancer patients would potentially benefit from target therapy with tamoxifen and trastuzumab, accordingly. Moreover, utilizing the novel transcriptional analysis measures has enabled the assessment of mRNA levels with microarray technology and provided the targeted therapy accordingly.

The Oncotype DX assay is 1 validated multiparameter test for recurrence prediction purposes in breast cancer. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has approved this quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test to be applied on paraffin-fixed breast tissue and evaluate 21 genes, including 16 cancer genes. The resultant recurrence score, varying from 0 to 100, would predict the course of a specific breast mass without lymph node involvement and hormone-receptor-positive, which was under tamoxifen therapy. The mentioned multigene panel was further examined in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project.[28]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of a new breast lump depends on whether the lump is benign or malignant and on the patient's physical health and personal wishes. Any patient with a proven or suspected malignant mass should receive management with an interprofessional approach, with input from the oncology, radiology, pathology, surgical, specialist nursing, anesthetic teams, palliative care, social workers, and psychology teams where indicated. Breast cancers are typically treated through surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, and immunological therapy.[6] Benign breast masses are treated according to etiology:

- Breast cyst: A simple breast cyst is usually involute without any intervention. They tend to recur if persistent or troublesome cyst aspiration may be an option. Cyst aspirate may be sent for cytological analysis, but there is some controversy as to the benefit of this due to the risk of false positives.[29]

- Fibroadenoma: These lesions are benign and usually involute without further treatment. A broad range of indications for interventions in beast fibroadenoma have been introduced, including rapid growth, greater than 3 cm size, an increase in the BI-RADS category, and tissue diagnosis suggestive of atypical hyperplasia or suspected phyllodes tumor. Despite the wide use of the open excision approach to managing breast fibroadenomas, ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted breast biopsy has been used for diagnostic confirmation before the definitive management.[30]

- However, if they are large, painful, or causing the patient distress, surgical consultation should be considered, and these are often removed surgically.[31] If there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, an excision biopsy should occur for diagnostic purposes.

- Fat necrosis and hematoma usually require no treatment other than analgesia and monitoring. However, the surgical consultant should consider whether the mass is causing the patient significant pain or cosmetic issues.[32]

- Breast abscess: In general, abscesses require surgical incision and drainage to identify and remove the source of infection. Smaller abscesses less than 3cm in size and lactational abscesses may resolve with oral antibiotics and needle aspiration, but there is a risk of recurrence.[33] In the primary setting, lactational abscesses should be treated with analgesia and oral antibiotics. Patients should be encouraged to continue breastfeeding with an onward referral for definitive management if possible. Abscess in a non-lactating patient or an unresolved, large, or multiloculated abscess may require admission for intravenous antibiotics and surgical or radiological drainage. Early breast specialist opinion should be sought in these cases.[34] Abscesses in a non-lactating female require referral to a triple assessment clinic to rule out underlying inflammatory breast cancer.[33]

- Gynaecomastia: In males presenting with gynecomastia, the investigation should focus on the likely cause, and if none can be found, further referral to endocrinology is recommended.[35]

- Mastitis: several standard antibiotic therapies have been introduced as the standard treatment for acute mastitis. The choice of antibiotic to be selected for the treatment differs considering the causative microorganism, antibiotic resistance profile, and positive history of recurrent mastitis. Accordingly, dicloxacillin- flucloxacillin, cephalexin, and clindamycin are standard treatments for staphylococcal mastitis, mastitis in patients with penicillin intolerance, and recurrent mastitis, respectively. The mentioned treatments should be offered for a full duration of 7 to 14 days.[36]

Differential Diagnosis

The likely differential of breast masses varies significantly depending on patient demographics. Generalized enlargement of breast tissue can be as simple as hyperplasia due to hormonal changes or drug-induced. It can even be related to liver pathology or, in some cases, muscular hypertrophy, as seen in athletes or bodybuilders. In female patients, the most common cause of a new breast mass is a fibrocystic disease, particularly among premenopausal women between 35 and 50. Fibrocystic changes, including simple and complex cysts, fibrosis, adenosis, and hyperplasia, are widespread, affecting more than 50% of women of reproductive age, and are usually asymptomatic.[37][38]

A new discrete breast mass in the context of fibrocystic disease is most likely to be a simple cyst, which usually presents as a fluctuant, well-circumscribed, smooth round lesion, which may or not be tender. Breast cysts commonly arise from distended lobules and are filled with serous fluid. These usually require no treatment and tend to go away by themselves. A simple cyst diagnosed with mammography does not require tissue biopsy, but a complex cyst or cyst containing debris should receive further investigation to rule out malignancy. Cysts may be multifocal or bilateral and can be recurrent. In post-menopausal women, the rate of fibrocystic disease increases with hormone replacement therapy.[29]

Breast adenosis describes enlargement and proliferation of the breast glands, and while not normally considered under the umbrella of a discrete breast mass, it can present with a generalized 'lumpiness' of the breast and should be considered a differential. It is common and often asymptomatic.[39] Among younger women, fibroadenomas are more common, accounting for over 50% of breast masses in females below 30.[40] A fibroadenoma is a biphasic mass containing a combination of glandular and stromal tissue. These are non-tender, firm, rubbery masses and tend to be highly mobile. A core biopsy is recommended if there is any diagnostic uncertainty following imaging.[31] These benign lesions are usually self-limiting; however, surgical treatment may merit consideration if a fibroadenoma is particularly large or causing the patient discomfort or cosmetic issues.

In high-risk women, particularly post-menopausal women or those with a history of high estrogen exposure, a malignant diagnosis is more likely. Malignant breast masses are more prone to be hard, nodular, irregular shape, and fixed to underlying or overlying tissues. Breast cancer must be considered a differential in all cases of a new breast mass, and a triple assessment is advisable if there is any uncertainty. Breast cancer can be divided into non-invasive and invasive cancers and classified according to cell type (eg, ductal, lobular, tubular) and hormone receptor status. Phyllodes tumors and Paget's disease of the breast are not always malignant. Still, they are usually considered in this category as they have a high malignant potential and need treatment.[6] Further detail as to the different types of breast cancer and their management is outside the scope of this topic. Of note, it is crucial to be aware that not all breast cancers are associated with a palpable mass; indeed, a large proportion is diagnosed via screening of asymptomatic individuals.

The vast majority of children presenting with discrete breast masses (>95%) are benign fibroadenomas. These usually require no treatment but require close monitoring as there are infrequent reports in the literature of pediatric breast cancers.[41] Males presenting with breast masses must be treated with a high degree of suspicion to rule out malignant tumors.[2] Imaging male breasts should utilize ultrasound as male breast tissue is not amenable to mammography. In males, central masses located behind the nipple may be attributable to gynecomastia. Gynecomastia is abnormal breast tissue development in males, which can correlate with several causes, including chromosomal disorders, liver failure, paraneoplastic syndromes, and drugs such as spironolactone and calcium channel blockers.[42] Due to hormonal variations, physiological gynecomastia may also be present in the neonatal period, at puberty, and in older males.[35]

Breast masses may arise due to local traumatic or infective etiology. A new breast mass on the background of recent trauma may represent fat necrosis or hematoma formation. These can arise following direct trauma to the breast or may be associated with surgery, biopsy, or radiation therapy. Fat necrosis is the term that describes the replacement of dead fatty tissue with scar tissue, which can present as a palpable, nodular, and occasionally tender lump due to its contrasting density with the surrounding tissue.[32] A hematoma is a blood collection under the skin or within the breast tissue and can also be characterized by scar formation.[43] A hematoma may also be associated with anticoagulant usage, in which case a review of anticoagulation is in order.[44] As these changes can resemble malignancy on imaging, a clear history must be emphasized to avoid unnecessary and potentially harmful invasive investigations.[32] A breast abscess is a localized collection of pus, usually arising as a complication of mastitis. Breast abscesses typically appear associated with lactation, as lactating mothers are at a higher risk of bacterial inoculation. The most likely causative organisms are staphylococcus and streptococcus. A breast abscess is likely to be extremely tender, with erythema and induration of the overlying skin.[33]

Prognosis

Several factors should be considered while interpreting the prognosis of a breast mass. Among them, sex steroid levels are significantly important. The endogenous sex steroids are well-established risk factors for breast cancer and result in a higher tumor growth rate in post-menopausal women. Moreover, the results of steroid hormone levels in a post-menopausal woman with a breast mass might predict the risk of developing breast cancer in up to 20 years. The risk of developing breast cancer directly correlates with the circulating sex hormone levels, and the 5 main determinants of circulating steroidal sex hormones are alcohol, exercise, diet, body weight, and smoking.[45][46]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The clinician must always approach a new breast mass from an interprofessional approach as the causes are diverse, and various teams carry out the investigations and treatments. The links between primary care, specialty, and subspecialty teams must be clearly defined, with an established protocol for clear and effective communication between the 2. A triple assessment clinic is an excellent example of a multidisciplinary clinic, as physicians or specialist nurses, clinical pathologists, radiographers, sonographers, and radiologists are involved. In this setting, interprofessional communication is encouraged and necessary to reach a consensus on the most likely diagnosis.[4] Treatment of breast cancers can involve an even more extensive range of specialists, including breast and oncoplastic surgeons, oncologists, radiation therapists, immunologists, genetic counselors, and nurse specialists who tend to take the lead in coordinating care.[47] In breast cancer, interprofessional care is the gold standard. It has proven to reduce mortality from breast cancer significantly, and all causes over 5 years.[48] This data demonstrates the importance of enhancing and prioritizing interprofessional relations to improve patient outcomes.