Introduction

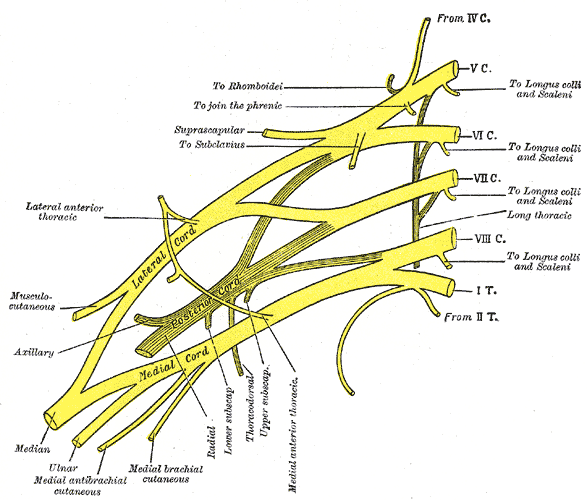

The brachial plexus is formed by the anterior primary rami of C5 through T1 and provides sensory and motor innervation of the upper extremity. The brachial plexus is divided, proximally to distally, into rami/roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and terminal branches. The trunks can be found within the posterior triangle of the neck, between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. The brachial plexus, along with the axillary artery, can be considered as a large neurovascular bundle that travels in the axilla to supply the upper extremity.

Structure and Function

The brachial plexus provides somatic motor and sensory innervation to the upper extremity, including the scapular region. As the brachial plexus travels through the posterior triangle of the neck into the axilla, arm, forearm, and hand, it contains various named regions based on how the plexus is formed. Ventral rami from spinal nerves C5 through T1, often referred to as roots of the brachial plexus, come together to allow their fibers to intermingle, forming superior, inferior, and middle trunks.

The 3 trunks continue from the posterior triangle into the axilla, with C5 and C6 roots forming the superior trunk, C8 and T1 roots forming the inferior trunk, and the C7 root continuing as the middle trunk.

Continuing from the trunks are bundles that are called divisions. Each of the trunks of the brachial plexus continues as an anterior and posterior division to form lateral, posterior, and medial cords.

The 3 cords (posterior, medial, and lateral) are formed from the anterior and posterior divisions, and they are named based on their relationship to the 2 parts of the axillary artery. The 3 posterior divisions converge to form the posterior cord while the anterior division from the superior trunk and the anterior division from the middle trunk join to form the lateral cord. The medial cord is formed as a continuation of the anterior division from the inferior trunk. The result of this “mixing” of nerve fibers is that the lateral cord contains components of C5, C6, and C7, the medial cord with contribution from C8 and T1, and the posterior cord carrying fibers from all levels of the brachial plexus (C5 to T1).

The final subdivision of the brachial plexus consists of five terminal branches containing different contributions from the C5-T1 spinal levels.

The branches, terminal and otherwise, of the brachial plexus are expanded below in the section Nerves and Muscles.

Embryology

Motor nerve fibers, like those found in the brachial plexus, arise from cells within the basal plate of the developing spinal cord and emerge to the ventral nerve root. The sensory nerve fibers found in the dorsal nerve root originate from neural crest cells. The dorsal nerve root will grow toward the ventral nerve root and will eventually join to form a spinal nerve. Spinal nerves will divide into dorsal primary rami and ventral primary rami. As the limb bud develops, nerves will elongate and grow into the limb in dermatomal and myotomal distributions.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The subclavian artery and its branches provide the majority of blood supply to the brachial plexus.[1] The trunks are supplied from muscular branches of the ascending and deep cervical arteries and sometimes muscular branches of the subclavian. Cords receive blood supply from the subclavian, axillary, and subscapular arteries.[1]

Nerves

Two nerves originate completely from the roots of the brachial plexus: the dorsal scapular nerve and the long thoracic nerve. The dorsal scapular nerve originates from the rami of C5, while the long thoracic nerve originates from the rami of C5, C6, and C7. Both nerves are often observed piercing the middle scalene muscle. The long thoracic nerve innervates the serratus anterior muscle and travels with the lateral thoracic artery. The dorsal scapular nerve innervates the levator scapulae muscle and rhomboid major and minor muscles and may travel with the dorsal scapular artery if present. There is also a contribution from the C5 root to the phrenic nerve.

Two nerves typically branch from the superior trunk, while the inferior and middle trunks are devoid of branches. The suprascapular nerve and nerve to the subclavius originate from the superior trunk and contain the spinal levels of C5 and C6. The suprascapular nerve travels through the scapular notch to provide innervation to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.

There are no branches from any division within the brachial plexus.

The majority of the branches of the brachial plexus arise from cords. Cords continue as 5 terminal branches while giving off seven other nerves ranging in function.

The lateral cord gives rise to a single nonterminal branch, the lateral pectoral nerve, that contains the spinal levels of C5 to C7 and innervates the pectoralis major muscle.

The medial cord gives off 3 nonterminal branches: the medial pectoral, medial brachial cutaneous, and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves. The medial pectoral nerve (C8-T1) innervates both pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles. The medial brachial cutaneous nerve innervates the medial side of the arm, while the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve innervates the medial side of the forearm.

The posterior cord typically has 3 nonterminal branches: the upper, middle, and lower subscapular nerves. The upper subscapular nerve (C5-6) innervates the subscapularis muscle, while the lower subscapular nerve (C5-C6) innervates the subscapularis and teres major muscles. The middle subscapular nerve (C6-C8), also known as the thoracodorsal nerve, innervates the latissimus dorsi muscle and travels with the thoracodorsal artery.

The 5 terminal branches of the brachial plexus are the musculocutaneous, median, ulnar, axillary, and radial nerves.

The musculocutaneous nerve (C5-C7) is completely formed by the lateral cord and provides motor innervation to the muscles of the anterior compartment of the arm: biceps brachii, coracobrachialis, and brachialis muscles. Once it gives off its motor fibers in the anterior compartment, the musculocutaneous nerve becomes the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve and provides cutaneous innervation to the lateral upper forearm.

The median nerve (C6-T1) is formed by contributions from the medial and lateral cords. It provides the majority of motor innervation to the musculature in the anterior forearm as well as the thenar compartment in the palmar hand. The nerve also provides cutaneous innervation to the lateral 3 1/2 fingers of the palmar hand. The main trunk of the median nerve innervates the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, and flexor digitorum superficialis muscles. The anterior interosseous nerve innervates the flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus, and the lateral half of the flexor digitorum profundus.

The C8-T1 ulnar nerve is completely formed by the medial cord. In the anterior forearm, the ulnar nerve innervates the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. It branches into a superficial branch and a deep branch in the hand. The superficial branch innervates the palmaris brevis muscle and provides sensory to the palmar surface of the little finger and the medial half of the ring finger. The deep branch of the ulnar nerve provides motor innervation to the muscles of the hypothenar and adductor-interosseous compartments of the hand.

The 2 terminal branches that originate from the posterior cord are the axillary nerve and radial nerve. The axillary nerve (C5-C6) enters the scapular region through the quadrangular space to innervate the deltoid and teres minor muscles. The radial nerve (C5-T1) is a continuation of the posterior cord and provides motor innervation to all muscles in the posterior arm and forearm. The main trunk of the radial nerve innervates the triceps brachii, anconeus, extensor carpi radialis longus, and brachioradialis muscles. In the cubital fossa, the radial nerve divides into the superficial branch of the radial nerve and the deep branch of the radial nerve. The superficial branch of the radial nerve innervates digits 1 to 3 of the dorsal hand cutaneously. The deep branch of the radial nerve innervates the supinator and extensor carpi radialis brevis muscles.

Physiologic Variants

One of the most common variants of the brachial plexus is contributions from C4 and T2.[2] The contribution from these spinal cord levels can vary. For example, a branch from C4 can be small, while the branch from T2 can be large. Even with the typical levels involved in the formation of the brachial plexus, the levels present in a given nerve can vary (See Netter image). This can lead to variation in dominant innervation to muscles or variation in dermatomal distribution.

Clinical Significance

Injury to the brachial plexus can occur during the birthing process. Forty percent to 50% of obstetric brachial plexus palsy cases are lesions to C5 and C6, more commonly known as Erb palsy.[3] Individuals with Erb palsy will hold the affected limb medially rotated at the shoulder, with the forearm pronated and the wrist flexed. Depending on how sever the injury is, treatment options vary. Infants with classical Erb’s palsy will recover spontaneously 90% of the time.[3] If the injury involves C5-T1 and there are no signs of significant improvement by the first 10 weeks of age, the infant is a candidate for surgery. Other treatment options include physical and occupational therapies.

Another pathology related to the brachial plexus is thoracic outlet syndromes (TOS). TOS is caused by the compression of the brachial plexus within the thoracic outlet. Symptoms include neck pain, trapezius pain, shoulder and/or arm pain, and chest pain.[4][5][6][7][8]