Introduction

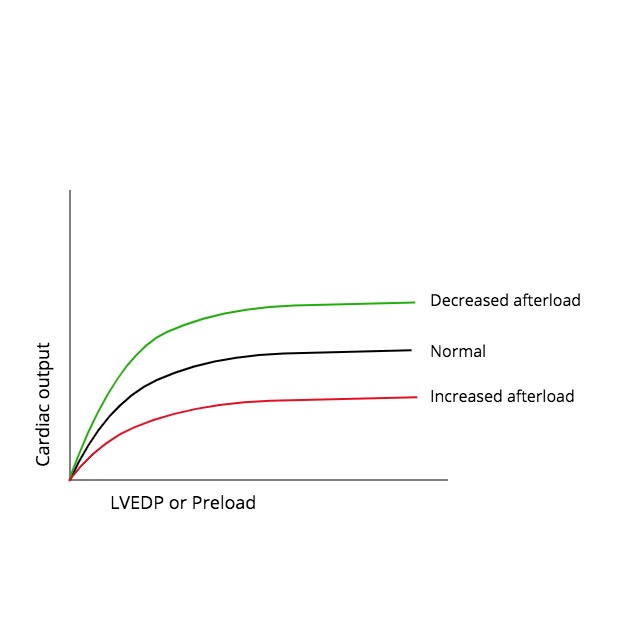

The systolic performance of the heart is determined by 3 factors: preload, afterload, and contractility. The direct relationship between preload and cardiac output was formulated in the early 1900s based on the work of Otto Frank and Ernest Starling. It led to the well-known Frank-Starling curves. Gordon et al. helped to elucidate the underlying mechanism for this phenomenon in their 1966 experiments involving sarcomere length-tension relationships. During this same period, extensive research demonstrated an inverse relationship between afterload and systolic performance, which is accepted today. This means that cardiac output decreases as the afterload on the heart increases and vice versa. Despite this simple concept, there has been substantial controversy over the best way to represent cardiac afterload.

The afterload of any contracting muscle is defined as the total force that opposes sarcomere shortening minus the stretching force that existed before contraction. Applying this definition to the heart, afterload can be most easily described as the "load" against which the heart ejects blood. The load on individual fibers can be expressed as left ventricular wall stress, which is proportional to [(LV Pressure x LV Radius)/ LV wall thickness], or [(P x r)/h]. However, the true equation is complex because it depends on the shape of the cardiac chamber, which is affected by several factors that are changing over time. Therefore, afterload cannot be represented by a single numerical value or described only regarding pressure. Arterial pressure (diastolic, mean, or systolic) is frequently used as a surrogate measure, but perhaps the best available techniques involve measuring systemic arterial resistance by various invasive and noninvasive methods. Several mathematical models have been developed using arterial impedance and pressure-flow relationships to characterize afterload better, but these are complex and less often utilized in practice. The inverse relationship between afterload and cardiac output is important in understanding the pathophysiology and treatment of several diseases, including aortic stenosis, systemic hypertension, and congestive heart failure.[1][2][3]