Introduction

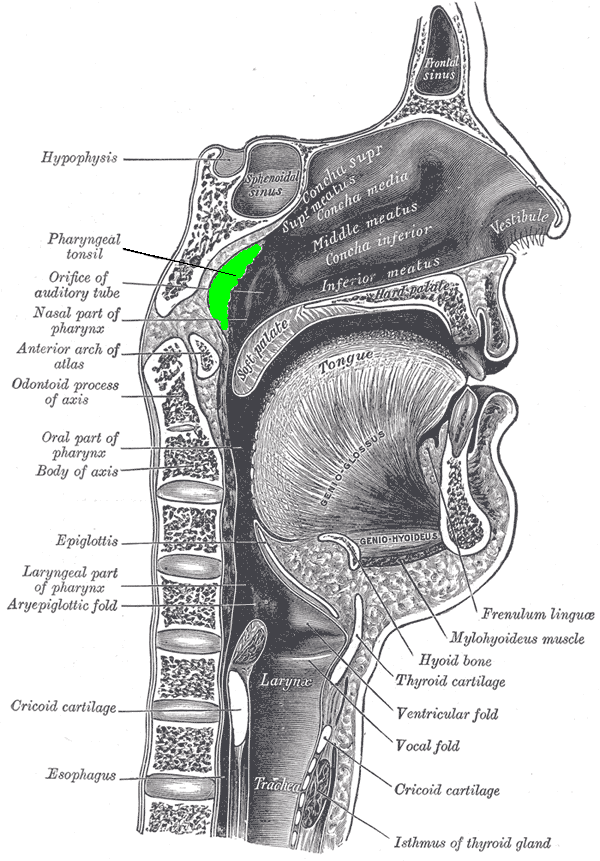

The adenoids exist as a rectangular mass of lymphatic tissue in the nasopharynx. Meyer first described this mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in 1868. The adenoids are midline structures situated on the roof and posterior wall of the nasopharynx. They form part of the Waldeyer ring, whose components include the adenoids, the palatine tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. They are present from the seventh month of gestation and typically grow until age 5. Adenoid tissue can be found extending to the eustachian tube opening and the fossa of Rosenmuller. The fossa of Rosenmuller is on the lateral wall of the nasopharynx, just behind the cartilage of the eustachian tube. These lymphoid masses have an important immunologic function, and hypertrophy can pose a risk for disease pathologies in children. Adenoids with other lymphatic tissue in the nasopharynx are the first line of defense against ingested or inhaled pathogens.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Adenoids are pyramidal in shape, with the apex of the pyramid directed towards the nasal septum, and the base of the pyramid present between the roof and the posterior wall of the nasopharynx. Their composition is of respiratory epithelium. Histologically, the lymphoid tissue of the adenoids divides into four lobes with seromucous glands interposed throughout the substance of the tissue.

As a portion of the Waldeyer ring, adenoids compose the lymphoid tissue that serves as a defense against potential pathogens in the pharynx. Adenoids, in conjunction with the lingual and palatine tonsils, are involved in the development of T cells and B cells. On the surface, adenoid tissue has specialized antigen-capture cells (ACC), M cells, which uptake the pathogenic antigens and then alert the underlying B cells. Activation of B cells leads their proliferation in areas called germinal centers; this helps in producing IgA immunoglobulins. Through this mechanism, the adenoids aid in the development of immunologic memory throughout childhood. Recent scientific literature has provided some evidence that adenoids also produce T lymphocytes (cellular immunity) like the thymus gland. The adenoids can function as a bacterial reservoir for the nasal cavity and are implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis.[1][3][2]

Embryology

The prenatal development of the head during embryogenesis consists of the neurocranium and the viscerocranium. The human face develops as part of the viscerocranium throughout the fourth to tenth weeks of fetal life. The fusion of two lateral primordia forms the adenoids during embryological development. Dysfunctional facial evolution may cause craniofacial deformities such as cleft palate and cleft lip.[1][4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The arterial supply of the adenoids is from the basisphenoid artery, the ascending pharyngeal artery, the ascending palatine artery, the pharyngeal branch of the maxillary artery, the tonsillar branch of the facial artery, and the artery of the pterygoid canal. The venous drainage of the adenoids is through the pharyngeal plexus. The pharyngeal plexus and the pterygoid plexus communicate, eventually draining into the facial veins and internal jugular veins. The lymphatic drainage of the adenoids is through the pharyngomaxillary space lymph nodes and the retropharyngeal lymph nodes.

Nerves

The nervous supply to the adenoids is via the pharyngeal plexus. The pharyngeal plexus contains fibers of cranial nerves IX, X, and XI. The innervation of the adenoids originates from the vagus (X) and the glossopharyngeal nerves (IX).

Muscles

The muscles found in the nasopharynx include the levator palatini and the pharyngeal constrictors. The superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle forms the superior aspect of the lateral walls of the nasopharynx.

Physiologic Variants

Adenoids decrease in size with age, typically atrophying completely by the teenage years. Persistence of adenoid tissue into adulthood is an uncommon clinical finding. Nonetheless, a disease process of the adenoids requires investigation in those presenting with symptoms of nasal obstruction. Immunocompromised patients, such as those diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and organ transplant recipients, can exhibit adenoid hypertrophy. The thinking is that this finding is thought to be caused by regressed adenoid tissue reproliferating in response to infections.[3][5]

Adenoid tissue may separate into two parts in some individuals. This variant can occur through two means: by a fissure extending from the pharyngeal bursa or by a median fold passing towards the nasal septum from the pharyngeal bursa.

Surgical Considerations

Adenoidectomy: An adenoidectomy is the surgical excision of adenoid tissue. Primary indications for adenoidectomy include otitis media with effusion of at least 3 months duration, chronic adenoiditis, obstructive sleep apnea lasting 3 months or greater, and recurrent upper respiratory infections. Patients post-adenoidectomy require special consideration for hemorrhage as a potential (though rare) complication. The basisphenoid artery supplies a portion of the nasopharyngeal tonsil and can be a potential source of bleeding post-operatively.[6]

Clinical Significance

Adenoid hypertrophy (AH): Impaired mucociliary clearance has been implicated as playing a role in adenoid hypertrophy, a condition typically seen in children. An enlarged adenoid may block breathing and be a cause of snoring or obstructive sleep apnea. Adenoid hypertrophy can also lead to comorbid conditions such as serous otitis and sinusitis. AH is higher in frequency in children with allergic diseases, with the most common allergen being house dust. Other risk factors noted for developing AH include cigarette smoke exposure and allergic rhinitis. In a child with these risk factors, AH should be a consideration during a routine examination. Assessing adrenal size can be achieved through flexible nasal endoscopy, where adenoid size grading is on a scale of I to IV. This scale represents the percentage of the posterior choana blocked by the adenoid tissue, with grade IV representing the highest level of obstruction. While adenoidectomy remains a common surgical treatment for adenoid hypertrophy, intra-nasal steroids are an option as a non-surgical treatment regimen.[7][8][6]

Adenoiditis: Adenoiditis refers to inflammation of adenoid tissue secondary to an infection. Those affected with adenoiditis may present with nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, mouth breathing, and cold-like symptoms. Adenoiditis may occur on its own or in combination with acute or chronic rhinosinusitis. Common pathogens leading to adenoiditis are often the same as those implicated in rhinosinusitis and include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Hemophilus influenza, and Moraxella catharrhalis. Nasal endoscopy showing purulent secretion of the adenoids can be useful to confirm adenoiditis.[1]

Other Issues

Adenoid faces: Adenoid faces describes the differences in physical characteristics seen in children with adenoid hypertrophy. The belief is that adrenal hypertrophy results in obstruction in proper nasal breathing, leading to mouth breathing and issues with dental and maxillofacial development. Adenoid faces characteristically demonstrate narrowed maxillary and dental arches, upper lip incompetence, retropositioning of mandibular incisors and hyoid bone, and a posterior-rotated mandible. There is also a downward tongue displacement and a lower position of the mandible. Removal of excessive adenoid tissue allows for the recovery of proper craniofacial growth.[9]