Continuing Education Activity

The 11th cranial nerve, also known as the accessory nerve, is prone to injury due to its long and superficial nature. Damage to the accessory nerve can be incidental, iatrogenic, or due to blunt trauma. This activity reviews the anatomy of the nerve and describes the evaluation and treatment of accessory nerve injury. It also highlights the role of interprofessional team members in managing this condition.

Objectives:

Assess the anatomy of the accessory nerve.

Identify the common and less common etiologies of accessory nerve injuries.

Determine the management considerations for patients with accessory nerve injuries.

Communicate the importance of a well-integrated interprofessional team in providing optimal evaluation and management of this condition.

Introduction

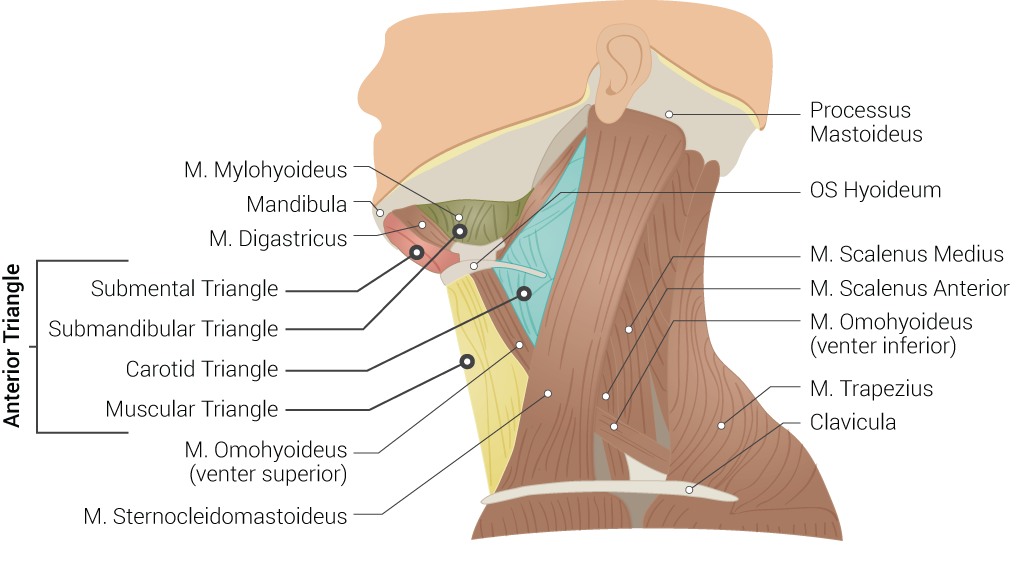

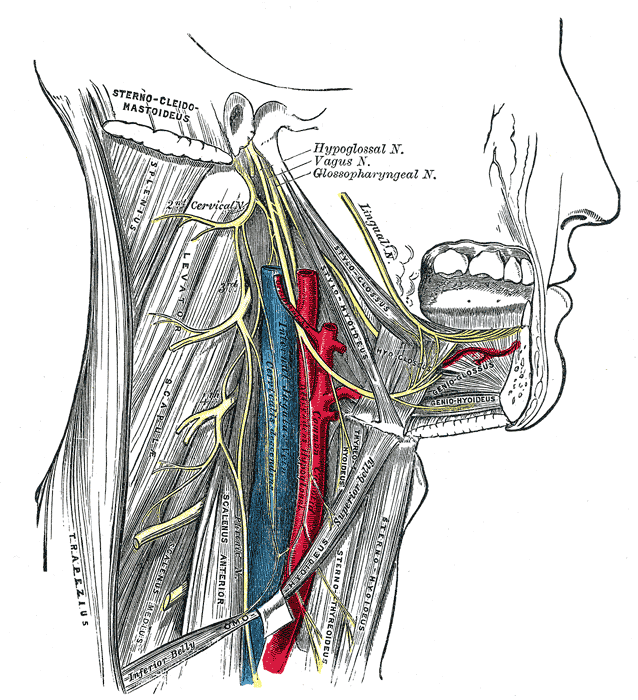

The cranial nerves are twelve pairs that travel outside the skull via foramina to innervate various structures. Cranial nerve (CN) XI is also known as the accessory nerve (see Image. The Accessory Nerve). According to the morphology of the cranial root of the accessory nerve, it is made of the union of 2 to 4 short filaments, making the cranial roots of the accessory nerve. Two to 9 rootlets join the spinal root to form the nerve. The cranial roots of CN XI could be considered part of the vagus nerve when factoring in the function of the 2 nerves. Both the cranial roots of the accessory nerve and the vagus nerve originate from the nucleus ambiguus and dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve and travel to the laryngeal muscles, supplying the motor fibers (see Image. Muscles of the Head, Face, and Neck).[1]

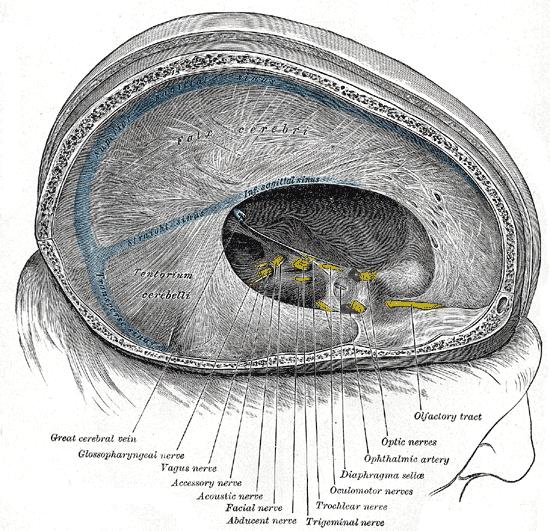

As the accessory nerve travels down and away from the brain, the cranial and spinal pieces of the nerve come together to form the spinal accessory nerve (SAN). The fusion of cranial and spinal contributions within the skull base forms the spinal accessory nerve. It exits the skull through the jugular foramen adjacent to the vagus nerve.[2] The spinal accessory nerve descends alongside the internal jugular vein, coursing posterior to the styloid process, posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) before entering the posterior cervical triangle (see Image. Superficial Neck Anatomy). The accessory nerve leaves the jugular foramen along with the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) and vagus nerve (CN X) (see Image. Dural Venous Sinuses). It travels to the SCM, either superficial or deep, and then enters the trapezius muscle, where a major accessory nerve trunk converges with C2, C3, or both. The traveling pathway of this nerve provides functional significance to the structures in the posterior neck. However, due to its long and superficial nature, the accessory nerve is prone to injury. Injury to the accessory nerve could be from blunt trauma, incidental, or, most commonly, iatrogenic reasons.[3]

Etiology

The most common cause for accessory nerve injury is iatrogenic, such as lymph node biopsies that involve the posterior triangle of the neck, neck surgeries including removal of a tumor, carotid or internal jugular vein surgeries, neck dissection (including radical, selective, and modified), or cosmetic surgery (eg, facelift) from the mechanical stress exerted on the neck due to positioning throughout the procedure. Other causes are penetrating trauma such as knife or gunshot trauma, blunt trauma from pressure, stress to the neck area from a sudden movement, or acromioclavicular joint dislocation affecting SCM. Other possible sources of injury are neurological, in which the nerve or the foramen it passes through are affected, leading to CN XI palsy. Examples are a tumor at the jugular foramen, which causes cranial nerve palsies such as Collet-Sicard syndrome, involving the cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII, and Vernet syndrome, involving the cranial nerves IX, X, and XI.[3]

Syringomyelia, brachial neuritis, poliomyelitis, and motor neuron disease are other possible causes of CN XI injury. Other examples are traction palsies to the brachial plexus and thoracic outlet.[4][5][6] Kassem et al suggested in a study that idiopathic brachial plexitis may affect the accessory nerve and could be sparked by surgeries.[7]

Certain neck surgeries can result in iatrogenic injury to the accessory nerve. These include the excision of benign neck growths, parotidectomy, endarterectomy, and internal jugular vein cannulation.[8][9]

Some sports injuries can cause accessory nerve damage, such as a hockey stick blow, a sling knot, wrestling, a noose in an unsuccessful hanging, and a "whiplash" injury.[10] Spontaneous isolated accessory nerve injury has also been observed.[11]

Epidemiology

The accessory nerve injury most likely occurs due to iatrogenic causes, such as posterior and lateral cervical triangle surgeries. The high likelihood of SAN injury with posterior and lateral neck surgeries led to exploring the various options with neck dissections, such as radical, selective, and modified neck dissections, in different studies.[4][5] According to a retrospective study by Popovski et al, the SAN injury rate postoperatively is the highest, with radical neck dissections at 46.7% compared to selective neck dissections at 42.5% and 25% in modified neck dissections.[6][12] Other studies suggest that preserving other structures, such as the nerve, muscles, and veins, would lead to fewer dysfunctions than more extensive procedures in the neck zones where only the nerve is preserved. Although other causes of cranial nerve XI injury are uncommon, they are explored as part of the etiology.

Iatrogenic SAN injury is most commonly seen following lymph node biopsies for diagnostic purposes in the posterior cervical triangle. These procedures reportedly result in 3 to 8% injury rates. Severe dysfunction of the upper extremity has been observed in up to 60% to 80% of radical neck dissections.[13]An extensive retrospective series observed clinical evidence of accessory nerve injury in 1.68% of the cases of modified radical neck dissection.[12]

Clinical evidence of accessory nerve injury has been observed to be 30% in selective neck dissections where cervical zones 2 through 4 and 5 were included. If zones 2 through 4 are dissected, and zone 5 is spared, this incidence decreases significantly.[14]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of the spinal accessory nerve injury depends on the etiology and mechanism of injury. Axonal injury is typically followed by Wallerian degeneration. This is evidenced by needle electromyography (EMG) and scar formation, which causes muscle atrophy and contractures.[11] Rarely is the spinal accessory nerve incidentally damaged while exploring the posterior triangle of the neck. In other cases, one of the small branches of the accessory nerve innervating the upper trapezius muscle may be damaged if it is not identified clearly during a neck dissection surgery. In nerve-sparing surgeries, the mechanism of injury is skeletonization, traction, and devascularization of the nerve. The resultant insults cause segmental demyelination because of local ischemia, leading to an under-functioning or completely dysfunctional nerve.[15]

Stretch on the accessory nerve impairs intraneural microvascular flow, causing ischemia and, subsequently, axonal rupture and degeneration. Usually, when stress on the accessory nerve due to traction is spread over a longer time, it is endured better than sudden and large stretches, as encountered in sudden acceleration-deceleration injuries.[10]

History and Physical

Evaluation of patients to diagnose SAN injury entails an organized clinical examination followed by electrophysiologic studies of nerves and muscles.[16] The most common and primary complaints of SAN injury are pain and weakness, mostly involving the shoulder. Radiation of pain is to the upper back, neck, and ipsilateral arm. Pain is exacerbated by the weight on the injured shoulder, which is not supported. The traction and straining of the muscles, such as rhomboids and levator scapulae, that work to compensate for the nerve injury could lead to more pain and decreased strength on the injured side. The combination of the pain and decreased strength would limit the range of motion of the involved shoulder.[3]

Pain may radiate to the upper back and neck and infrequently to the ipsilateral arm. This pain has a multifactorial etiology and may include straining of involved muscles with subsequent brachial plexus stretching.[14][10] The deformity associated with this phenomenon affects regular daily activities, such as placing dishes on overhead shelves and physical activities involving weight-bearing on the shoulders.

Pain around the shoulder joint and neck area can be assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS) comprised of 10 points.[17] The mean score observed in SAN-related shoulder syndrome is around 7 (range is 6 to 9).[18]

The most common sign is the noticeable asymmetry on the shoulder and upper back inspection. The patient would present with a diminished ability to hold the shoulder in abduction, shoulder drooping, and ipsilateral scapular winging (in which the medial side of the scapula is more prominent than the unaffected side).[19] A limited active range of motion may eventually progress to worsening the passive range of motion, causing adhesive capsulitis. Other possible findings are atrophy of the trapezius (depending on the length of the injury) and internal rotation of the humeral head. Hypertrophy or subluxation of the sternoclavicular joint may occur due to abnormal stress on the medial head of the clavicle following the loss of support from the trapezius muscle.[20]

Restriction in the range of motion (ROM) is observed as follows:

- Active abduction: 30 to 140 degrees

- Active forward flexion: 50 to 180 degrees

Evaluation

There are some pitfalls in establishing a diagnosis of accessory nerve injury. For instance, the trapezius muscle has a dual nerve supply, resulting in some residual motor function following SAN injury. This can make spinal accessory nerve injury challenging to diagnose. Trapezial dysfunction results in subjective symptoms secondary to contralateral paresthesias, myofascial pain syndromes, and radiculitis. These variable presentations also make it difficult for providers to diagnose spinal accessory nerve injury promptly. Different presentations are also attributable to the anatomic extent of SAN injury, collateral tissue damage, and variable pain thresholds.[19]

Ultrasound, such as high-resolution ultrasonography (HRUS), has been used to confirm the target nerve and visualize the structures surrounding the nerve. Ultrasound helps detect some changes to the muscles, such as atrophy. Ultrasound guidance to correct target areas may also help reduce possible damage during injections and medication administration. Ultrasonography does not help detect the actual transaction of the nerve.[2][21]

Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies are not necessary for the diagnosis; however, it would be useful to distinguish and quantify the degree of damage by doing serial EMGs. Electrodiagnostic tests are considered the most sensitive for assessing nerve conduction impairment.[14] In nerve injury, nerve conduction studies show prolonged latencies, while EMG could reveal signs to suggest denervation or reinnervation based on the timing of the study.

EMG has shown that the trapezius is the primary muscle responsible for shoulder elevation, and through its upper bundle, it takes part in arm elevation. Nonetheless, this movement also involves the participation of the deltoid, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus muscles. For these reasons, certain spinal nerve mononeuropathy may be missed by healthcare providers because the action of the other muscles responsible for arm elevation may compensate for the movement.[21]

Electrodiagnostic tests help plan a physical therapy regimen to minimize postoperative morbidity.[14] They are also used intraoperatively to monitor the SAN nerve for identification and preservation.

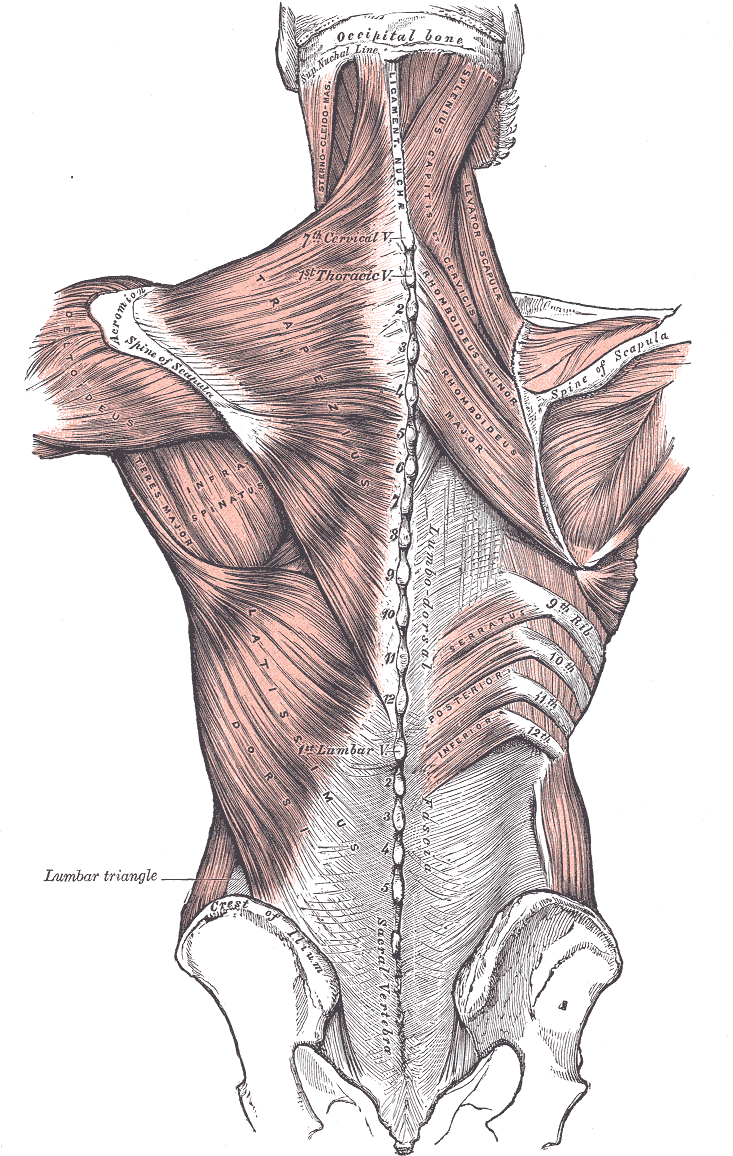

Kim et al observed that in nerve conduction studies of the spinal accessory nerve, the most appropriate site for recording in the upper trapezius is the middle point between the acromion and the C7 spinous process. In the middle trapezius, this site is the meeting point between the middle and lateral one-third of the line, joining the root of the scapular spine to the vertebral spine (see Image. Posterior Axioappendicular Muscles).[22]

Shoulder function is clinically evaluated in the following ways:

- Goniometry - for a range of motion assessment to evaluate movements, such as flexion and abduction around the shoulder joint

- Manual measurement of muscle strength in elevation, flexion, and abduction[23]

The disease-specific questionnaires to assess the quality of life (QOL) are sensitive tools for evaluating shoulder movements and strength. Some more commonly validated questionnaires for shoulder-specific evaluations are:

- The University of Washington's quality-of-life scale

- The neck dissection impairment index

- The shoulder disability questionnaire (SDQ)[24]

Intraoperative diagnosis is heavily reliant on intuition. A provoked shoulder motion due to cautery or dissection should be carefully assessed. Clinical examination of the motor function postoperatively is optima. Additionally, the area must be widely explored during surgery to rule out the possibility of any inadvertent injury.[19]

Treatment / Management

The severity and the cause of the SAN injury would be important factors in determining whether the treatment is surgical, such as re-anastomosis and nerve grafting, or nonsurgical, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), nerve stimulation, and local/ regional nerve-blocking and physical therapy and rehabilitation. Immediate therapy should be considered for severe presentations, such as penetrating traumas and iatrogenic injuries. Generally, 2 options for treatment are available: medical and surgical. The approach to managing accessory nerve injury and resulting trapezius muscle deformity is an interprofessional approach that revolves around conservative care, physical therapy, and surgical treatment.

Medical Treatment

Indications for medical management include:

- Serial clinical evaluation showing improved shoulder function

- Electrical regeneration on EMG or clinical improvement

- Mild and subjective symptoms, such as pain; and mild scapulohumeral dysfunction

Short-term options for the relief of shoulder pain and improved function are:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Regional nerve blocks with local anesthetics (requiring frequent repeat injections)

- Transcutaneous nerve stimulation

These options are unfeasible for long-term management.[25]

Rehabilitation

Physical and occupational therapy are useful ways of providing significant functional benefits. Rehabilitation aims to gradually promote a wide passive ROM and active motion to avoid the development of shoulder dysfunction because of adhesive capsulitis.[26] Keeping the shoulder aligned is excessively important for rehabilitation as it reduces the mechanical traction on the scapula and shoulder region. Elevation of the scapula minimizes the level of dysfunction of the trapezius muscle.[27] The following recommendations should be made to the patient:[10]

- Do not carry heavyweights on the affected side

- Hook the thumb or put the whole affected hand in the pants pocket, which can give significant relief

- Use an arm sling to help with pain, but this can be counterproductive as it can hamper the function of the affected arm

Orthoses have also been used for rehabilitation. In one study, orthosis was observed to be associated with improvement. Despite this improvement in pain and function, the active shoulder abduction only improved by 5 to 25 degrees; therefore, this improvement should not be confused with the return of trapezial function.[27]

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy (PT) is an essential part of recovery from shoulder dysfunction secondary to spinal accessory nerve injury. It becomes crucial for patients who refuse or are unsuitable for surgical treatment. PT aims to sustain passive ROM around the shoulder. This helps avoid shoulder stiffness resulting from malalignment and adhesive capsulitis. A study observed 2 groups: the PT group (with physical therapy) and the non-PT group (without physical therapy).[26] Neck dissection was carried out in all patients with preservation of the spinal accessory nerve. The PT group showed significantly improved mobility, pain, overall quality of life, and earlier return to the previous occupation. The investigators emphasized early and extended PT, starting within 1 month of surgery and extending for 3 months. However, recent studies suggest that PT is worthwhile for late-diagnosed SAN injuries.[28] A study by McGarvey et al revealed that scapular strengthening exercises after SAN injury post-neck dissection could maximize shoulder abduction.[29]

Eventually, aggressive PT is critical to maintaining shoulder function and alleviating pain. Serial EMG and clinical examinations are useful in monitoring SAN function. However, early surgical treatment yields the best outcomes.[19]

Surgical Therapy

When there is no apparent nerve injury or resection, the decision to carry out the surgical intervention should only be made after serial assessments following the initial injury fail to show spontaneous recovery in trapezial function and confirm persisting neurologic deficits. Indications for surgical intervention are the following:

- Dense paralysis

- Absence of EMG or clinical improvement on sequential assessments

- Troubling subjective symptoms, such as pain or severe scapulohumeral malfunction

- Intraoperative spotting of a nerve-in-continuity that fails to show contractions on direct stimulation [19]

The surgical interventions are as follows:

- Neurolysis [30]

- [30][30]Primary nerve anastomosis [31]

- Cable graft, such as autograft, biosynthetic nerve guide, or Neurotube [32][33]

- Eden-Lange muscle transfer [34]

Serial examinations may distinguish patients suitable for surgical intervention from those who could be managed conservatively. In a patient with an obvious spinal accessory nerve transaction, urgent reconstruction is recommended. In the cases of trapezius muscle palsy in the presence or absence of a history of neck dissection, the surgeon must establish the length of time from the onset of symptoms. The Eden-Lange muscle transfer is recommended for patients with spontaneous trapezius palsy or where the patient has been symptomatic for more than 20 months.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for accessory nerve injury include the following

- Long thoracic nerve injuries that cause paralysis or weakness of the serratus anterior muscle present as winging of the scapula, which is worse with lift-forward arm flexion or pushing the outstretched arm against a wall. This is different from accessory nerve injury, which has winging of the scapula with the abduction of the arm

- Rotator cuff injury has a similar presentation when lifting the arm behind the head, except this injury does not present with winging of the scapula

- Shoulder girdle arthritis and pain syndrome do not have muscular atrophy and winging of the scapula

- Whiplash injury could cause neck pain, cervical spine rigidity, and limited neck motion secondary to spasms and pain

Prognosis

Various factors influence spinal accessory nerve (SAN) function after an insult, such as the type of neck dissection, the extent of injury, radiation therapy, the interval between trauma and repair, the vascularity, and the length of the graft.[35]

In a study in which half of the patients received primary nerve repair and half of the patients received nerve graft, it was found that the recovery time ranged between 4 to 10 months.[26][36][37] However, one of the most important contributors to a better prognosis is an early referral, which leads to a more accurate diagnosis and appropriate intervention. Also, the early operative intervention has better results in regaining functionality, whereas delayed diagnosis and treatment run the risk of less effective treatment and less predictable results.[38][39][40]

A study by Eickmeyer et al observed that in neck cancer cases, patients who underwent nerve-sparing neck dissection did better in terms of residual function as opposed to patients who were managed with nerve-sacrificing dissection. Additionally, a correlation was seen between decreased scores on QOL measures and reduced shoulder flexion and abduction. Those who did not undergo neck dissection showed the best level of function.[41]

Complications

A patient with an injury to the SAN may present with neck pain, asymmetrical shoulders, inability to shrug the shoulder, or weakness in the neck area. The patients can also have complications secondary to treatment. Complications secondary to nerve graft include the formation of a neuroma or fibrotic ingrowth over the graft, interfering with proximal axonal sprouting, leading to graft failure. This complication occurred in patients who had radiotherapy postoperatively or where a long and nonvascular type of graft was used. Another complication is associated with harvesting the autologous nerve graft that results in the morbidity of the donor site.

Deterrence and Patient Education

If the patient undergoes a surgical nerve repair, proper advice should be given on restricting motility and caring for the wound. The importance of physiotherapy, when needed, should always be stressed. Initially, they should be told about weekly follow-ups for approximately 6 weeks, followed by monthly follow-ups thereafter. The patients should be advised to report any improvement or decline in their clinical state, pain, and shoulder function.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional assessment and management must be implemented for early detection and prompt management of patients suffering from accessory nerve injury due to any cause. The nurse practitioner and primary care provider must refer any patient unable to shrug the shoulder or asymmetrical shoulders to a neurologist to determine the cause and treatment. Coordination of care for the patient is crucial, with physical and occupational therapy playing a significant role in better recovery and improved outcomes.