Introduction

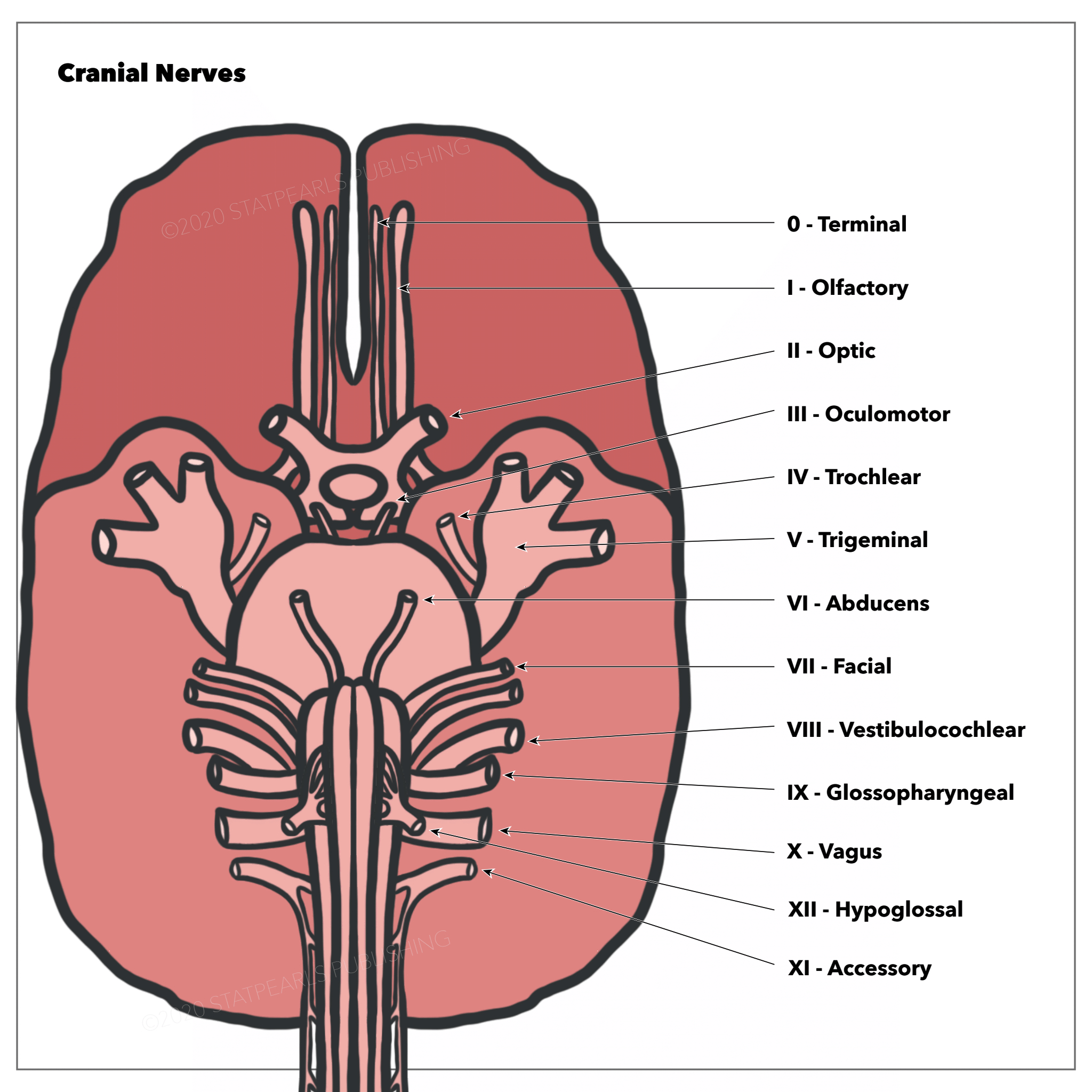

Cranial nerve six (CN VI), also known as the abducens nerve, is 1 of the nerves responsible for the extraocular motor functions of the eye, along with the oculomotor nerve (CN III) and the trochlear nerve (CN IV). See Image. The Cranial Nerves.

Structure and Function

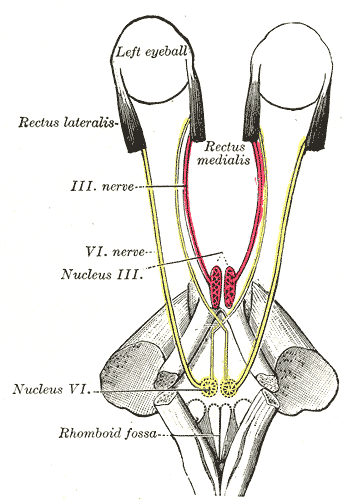

Unlike the oculomotor and trochlear nerve, the abducens nerve is a purely motor nerve, meaning the nerve has no sensory function (see Image. The Abducens Nerve). Its main function is to carry general somatic efferent nerve axons to innervate the lateral rectus muscle, which then abducts the eye on the ipsilateral side. It is also secondarily involved in the innervation of the contralateral medial rectus muscle through the medial longitudinal fasciculus so that both eyes move laterally in a coordinated manner.[1][2][3]

Embryology

The abducens nerve is formed embryologically from the derivatives of the somatic efferent column of the basal plates of embryonic pons.

Nerves

The nerve can be divided into 4 distinct portions: the nucleus, the cisternal portion, the cavernous sinus portion, and the orbital portion. The abducens nucleus resides in the dorsal pons, ventral to the floor of the fourth ventricle, and just lateral to the medial longitudinal fasciculus. About forty percent of the axons project through the ipsilateral medial longitudinal fasciculus to cross over to the contralateral medial rectus subnucleus to eventually innervate the contralateral medial rectus muscle. The pontine branches of the basilar artery supply the abducens nucleus.

The abducens nerve has the second longest intracranial course of all the cranial nerves. It is located in the pons at the floor of the fourth ventricle, at the same level as the facial colliculus. The axons of the facial nerve loop around the posterior aspect of the abducens nucleus. This is of clinical significance later. The nerve originates from the caudal, dorsal pontine below the fourth ventricle. After the fibers emerge from the nucleus, they course superiorly and then anteriorly before most axons leave the brainstem at the junction of the pontine and the medulla (ie, the pontomedullary groove) caudal and medial to both the facial nerve and the vestibulocochlear nerve in most cases.

The nerve then travels through the subarachnoid space. It crosses the upper edge of the tip of the petrous part of the temporal bone towards the clivus within a fibrous sheath called Dorello's canal. It enters the dura inferior to the posterior clinoid process. Because it is anchored in Dorello's canal, the nerve is prone to stretching when intracranial pressure is increased due to multiple causes discussed later. It then enters the cavernous sinus (along with the oculomotor nerve, the trochlear nerve, and the first branch of the trigeminal nerve (V1), following lateral to the internal carotid artery and medial to a lateral wall of the sinus before following the sphenoidal fissure and entering the orbit through the superior orbital fissure within the tendinous ring to reach its destination at the lateral rectus muscle.

Muscles

The abducens nerve functions to innervate the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle and partially innervate the contralateral medial rectus muscle (at the level of the nucleus - via the medial longitudinal fasciculus).

Physiologic Variants

A few physiologic variants of abducens nerve anatomy have been documented. Three variants were found in a study of 20 cadaveric heads (40 nerves). Variation I was found in 70% of cases where the abducens nerve was a single trunk. Twenty percent of cases had variation II, branching of the nerve exclusively within the cavernous sinus. Lastly, 10% of cases had variation III, duplication of the abducens nerve.[4]

Surgical Considerations

The abducens palsy can be an early sign of raised intracranial pressure or a pontine glioma. There is a chance of injury to this nerve during the extended endoscopic transnasal surgeries for skull base lesions. The Gruber ligament can act as a useful landmark in this regard.[5]

Clinical Significance

The incidence of unilateral abducens nerve palsy in head trauma ranges from 1% to 3%. Compromise of the abducens nerve results in the inability to abduct the ipsilateral eye and a partial decrease in the ability to adduct the contralateral eye. This manifests in the patient as diplopia or double vision due to the unopposed action of the medial rectus. This vision is worse at a distance, and the patient has an esotropia on the primary gaze. Patients may also present with a head turn or strabismus to maintain binocularity and binocular fusion to minimize diplopia. Since some fibers cross as described above, the lack of a contralateral adduction defect makes it easy to differentiate a lesion in the abducens nucleus before the medial longitudinal fasciculus from a lesion beyond the medial longitudinal fasciculus. The patient could not abduct the affected eye past the midline during the physical exam. They also complain of worsening diplopia on attempted lateral gaze.[6][7][8]

Damage to the abducens nerve can be caused by anything that compresses or stretches it, such as tumors, aneurysms, fractures, or increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Other general causes include damage to the nerve's blood supply (strokes), demyelinating syndromes, infectious processes such as meningitis, or various neuropathies.

Damage to the abducens nerve is frequently seen in children as a post-viral syndrome. However, these patients should get an extensive workup to rule out neoplasm as a cause of palsy. Adults require a less extensive workup because the most common cause of abducens nerve palsy in that population is ischemic neuropathy. In adults, common risk factors for a compromised vascular supply include older age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Of those, the most common cause of abducens nerve palsy is diabetic neuropathy.

Damage to the abducens nerve can result from anything that compresses it. Some causes of palsy due to compression could be malignancy, aneurysms, or head trauma, leading to nerve impingement anywhere along its intracranial courses, such as in the middle fossa, the cavernous sinus, or the orbit itself.

Similarly, processes that cause downward pressure on the brainstem can stretch the abducens nerve along the clivus. Some of these processes include a brain tumor, hydrocephalus, pseudotumor cerebri, intracranial hemorrhage, or edema. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is a condition associated with bilateral abducens nerve palsy.

Viral or bacterial infections of the central nervous system may also damage the nerve. To exclude meningitis in patients with no history of diabetes or hypertension and a negative head CT scan for other pathology, a lumbar puncture (LP) for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is completed.

Treatment of a sixth nerve palsy is dependent on the underlying cause. If the cause is a viral infection, the palsy resolves itself over time, along with other symptoms of the viral infection. If due to a compromised vascular supply, treatment should be targeted toward minimizing the concurrent risk factors that impair microvascular circulation. If it is due to compression, surgery, chemotherapy, or other procedures to correct the cause of mass effect on the nerve. Corticosteroids can also reduce nerve tissue inflammation from those underlying causes.

Other Issues

Due to the neuroanatomy of the abducens nucleus and its proximity to the fibers of the facial colliculus, infarcts affecting the dorsal pons can produce an ipsilateral facial palsy and a lateral rectus palsy. Similarly, infarcts of the ventral pons can affect the fibers of the abducens nerve as it exits the pontomedullary junction near the corticospinal tract. This produces a contralateral hemiparesis (remember that the corticospinal tract's fibers cross at the medulla's level).

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (WKS) is another syndrome associated with abducens nerve palsy. It is usually associated with thiamine deficiency due to excessive alcohol use. The classic triad patients present with confusion, ophthalmoplegia, and ataxia. The ophthalmoplegia results from atrophy of the floor of the fourth ventricle, as well as other regions of the brain (the mamillary bodies, the thalamus, the periaqueductal gray, the walls of the third ventricle, the cerebellum, and the frontal lobe). As stated above, this can affect the fibers of the abducens nerve and result in horizontal nystagmus.[9]