Continuing Education Activity

Spontaneous intestinal perforation in the newborn is defined as a single bowel wall perforation typically occurring in the terminal ileum. It is a life-threatening condition that affects very low birth weight infants (birth weight of less than 1500 g) and extremely low birth weight (birth weight of less than 1000 g) infants. The exact pathophysiology of spontaneous intestinal perforation is a subject of debate. Prematurity and low birth weight are significant risk factors. Diagnosis relies on the typical radiographic finding of pneumoperitoneum. Spontaneous intestinal perforation is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Timely diagnosis, prompt surgical consultation, and management are of utmost importance. This activity reviews the incidence, pathophysiology, and role of the interprofessional team in managing spontaneous intestinal perforation.

Objectives:

- Review the clinical presentation of spontaneous intestinal perforation.

- Describe the evaluation of infants with spontaneous intestinal perforation.

- Summarize the management recommendations for spontaneous intestinal perforation.

- Outline the prognosis for infants with spontaneous intestinal perforation.

Introduction

Spontaneous intestinal perforation of the newborn, also known as focal intestinal perforation or isolated perforation, is a single intestinal perforation typically occurring at the terminal ileum. It is a life-threatening condition that affects very low birth weight infants (birth weight <1500 g) and deficient birth weight infants (birth weight <1000 g).

Spontaneous intestinal perforation is associated with high morbidity and mortality. The perforation location is most commonly focal and involves the antimesenteric border of the terminal ileum.[1] The jejunum and colon are other possible locations for spontaneous intestinal perforation.

Etiology

Even though the exact etiology of spontaneous intestinal perforation is speculative, prematurity is the significant risk factor for developing this condition. Several other antenatal and postnatal risk factors have been described as follows:

Antenatal

Severe maternal chorioamnionitis with collective evidence of fetal vascular response is reported to be a risk factor for the development of spontaneous intestinal perforation. Antenatal medications such as glucocorticoids, indomethacin, and magnesium sulfate have been linked to spontaneous intestinal perforation in extremely low birth weight infants but remain a topic of debate.[2]

Additional risk factors include perinatal conditions associated with fetal hypoxia, such as maternal preeclampsia, oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth restriction, low activity (tone), pulse, grimace, appearance, and respiration (APGAR) scores.[3][4][5][6]

Postnatal

Early postnatal glucocorticoids have been associated with an increased incidence of spontaneous intestinal perforation. This was first described by a randomized controlled trial for early postnatal hydrocortisone for chronic lung disease, which showed improvement in respiratory outcomes but with an increased risk of spontaneous intestinal perforation. There is some recent evidence for using a lower dose of hydrocortisone to improve respiratory outcomes without increasing the risk of spontaneous intestinal perforation.[7]

Early indomethacin was associated with spontaneous intestinal perforation if combined with dexamethasone.[8] However, the association of indomethacin alone with spontaneous intestinal perforation remains a subject of debate.[9][10][11][12]

Candida and coagulase-negative staphylococcus epidermidis have been isolated from the peritoneal cultures in cases of spontaneous intestinal perforation. It is unclear whether these infections were a cause of spontaneous intestinal perforation or post-perforation infections since these are the normal gastrointestinal colonizers in extremely low birth weight infants.

Early enteral feeding in extremely low birth weight infants is associated with decreased incidence of spontaneous intestinal perforation.[13] Components of breast milk and colostrum such as arginine, glutamine, threonine as well as polyunsaturated fatty acids are thought to improve the structural integrity of the intestinal wall.[14]

Epidemiology

The incidence of spontaneous intestinal perforation is reportedly 1 to 2% for very low birth weight infants (birth weight of less than 1500 g) and 5 to 8% for extremely low birth weight infants (birth weight of less than. 1000 g.)[15][16]

The incidence of spontaneous intestinal perforation increases with decreasing gestational age. Spontaneous intestinal perforation is reported more frequently in male infants than female infants. There have also been a few reports of spontaneous intestinal perforation in term infants.[17]

The median age of perforation is seven days, with a range of 0 to 15 days.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of spontaneous intestinal perforation in the newborn is unknown, and several mechanisms have been proposed.

It is speculated that spontaneous intestinal perforation occurs because of bowel wall ischemia and deficiency of muscularis propria. This is supported by the association of spontaneous intestinal perforation with conditions such as patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), which may compromise intestinal blood flow, and the usage of indomethacin is known to cause mesenteric vasoconstriction. Further, the most common location for the occurrence of spontaneous intestinal perforation is the terminal ileum, which is a watershed region and prone to ischemia. However, the histopathology of spontaneous intestinal perforation reveals a focal area of perforation in the absence of inflammation, ischemia, or extensive necrosis.

Association of spontaneous intestinal perforation with antenatal or postnatal glucocorticoids followed by exposure to early indomethacin has been linked to the changes in nitric oxide synthase production in the intestinal and neuronal smooth muscle. Stressors such as maternal chorioamnionitis, oligohydramnios, and low APGAR scores can also cause a premature surge of cortisol. It is postulated that inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) by steroids, along with the inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by the indomethacin, may lead to disruption of intestinal motility.[18]

Further, glucocorticoids cause mucosal hyperplasia at the expense of submucosal thinning, leading to necrosis of the submucosal layer, which increases the vulnerability to intestinal perforation in deficient birth weight infants.[19] Return of bowel motility after the transient ileus caused by the combination of indomethacin and glucocorticoids leads to increased intraluminal pressure in an already compromised intestinal wall leading to perforation of the bowel.

Early enteral nutrition has been shown to reduce the incidence of spontaneous intestinal perforation.[13] Timing, type, and mode of enteral nutrition impact the overall integrity of the intestines as well as immune function. Components in breast milk such as arginine, glutamine, threonine, and polyunsaturated fatty acids in the colostrum have been shown to have protective effects on the intestinal wall by promoting improved structure and function.[20]

Infection may also have a role in the pathogenesis as evidenced by the isolation of pathogens such as candida and coagulase-negative staphylococcus from the peritoneal fluid cultures and the resected intestinal specimens.

Histopathology

On histopathologic exam, isolated hemorrhagic necrosis with a focal area of perforation is the typical finding in spontaneous intestinal perforation. Mucosal villus architecture is usually preserved, and thinning of muscularis propria can be observed. Bowel proximal and distal to the perforation usually appears normal.

History and Physical

Signs and symptoms of spontaneous intestinal perforation are highly variable. Infants present with acute onset of abdominal distension. A blue-black discoloration of the abdominal wall may be seen. As the condition progresses, metabolic acidosis and systemic signs, including tachycardia and hypotension, may be evident as a marker of peritonitis.[21]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of spontaneous intestinal perforation is based on the characteristic clinical presentation.

Laboratory findings are usually non-specific and may include:

- Leukocytosis

- Anemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Elevated liver function tests, including serum alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels

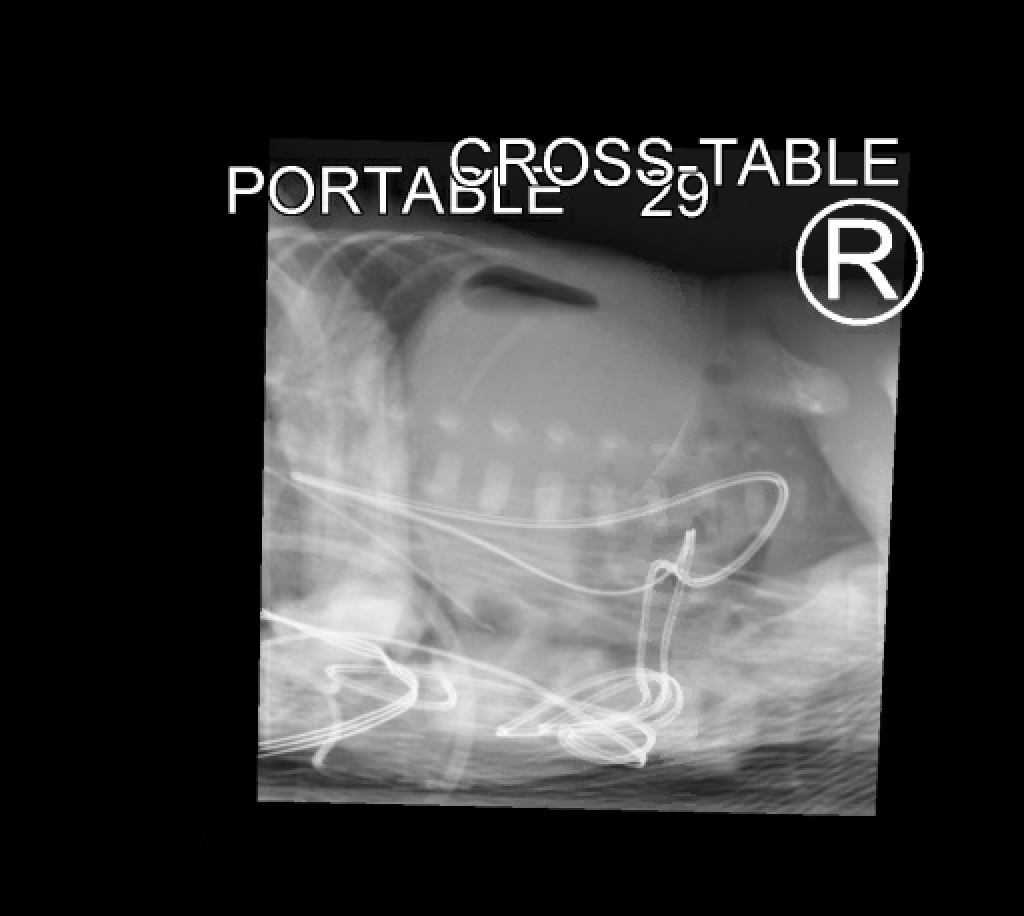

Diagnosis of spontaneous intestinal perforation can be confirmed by the typical radiographic findings of pneumoperitoneum. Supine and lateral decubitus or cross-table lateral views must be obtained.[15] In some cases, an abdominal ultrasound may help detect echogenic free fluid in the peritoneal cavity.[22]

Treatment / Management

Spontaneous intestinal perforation has a high mortality rate, and prompt management is of utmost importance.

Medical Management

All enteral feeds and medications must be discontinued, and a nasogastric tube or orogastric tube must be inserted at low intermittent or continuous suctioning to decompress the abdomen. Total parenteral nutrition must be started for nutrition.[13] In cases of hypotension, inotropic medications should be started. Intravenous empiric antibiotics should be initiated.[23]

Surgical Management

Surgical management of spontaneous intestinal perforation includes bedside primary peritoneal drainage and laparotomy.[24] Laparotomy with resection of the affected intestine and creation of a stoma is the traditional surgical approach. Primary peritoneal drainage is frequently considered as temporary management in infants who are unstable to tolerate laparotomy. However, recent studies have looked at primary peritoneal drainage as definitive management and found comparable outcomes to laparotomy.[24]

A multicenter retrospective study comparing the short-term outcomes of infants with spontaneous intestinal perforation treated with primary peritoneal drainage versus laparotomy found that the time to full feeds and length of stay were similar.[25]

In a large prospective multicenter randomized trial of 310 extremely low birth weight infants (birth weights of less than 1000 g) with necrotizing enterocolitis or spontaneous intestinal perforation, there was no significant difference in the rates of mortality or neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 22 months corrected age between infants randomized to initial laparotomy versus initial peritoneal drainage.[26]

However, due to the rarity of the occurrence of spontaneous intestinal perforation, as well as the emergent nature of the intervention required, the studies have been limited in terms of evaluating the difference in outcomes for different management based on the severity of disease, intraoperative diagnosis as well as role of disease progression on the outcomes.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis to consider is necrotizing enterocolitis. Necrotizing enterocolitis is also a gastrointestinal condition in infants with extremely low birth weight. Signs and symptoms of necrotizing enterocolitis overlap with that of spontaneous intestinal perforation. Due to these similarities, both conditions are frequently studied together. It is, however, extremely important to distinguish spontaneous intestinal perforation from necrotizing enterocolitis, as they have different pathophysiology and risk factors as well as mortality and other outcomes.

Spontaneous intestinal perforation can be differentiated from necrotizing enterocolitis based on the following factors:

- Spontaneous intestinal perforation appears earlier in life than necrotizing enterocolitis. The median age of presentation for spontaneous intestinal perforation is seven days compared to 14 days for necrotizing enterocolitis. In general, infants with spontaneous intestinal perforation are significantly more premature and have a smaller birth weight than infants with necrotizing enterocolitis.

- Antenatal infection and medications have been reported as risk factors for developing spontaneous intestinal perforation. Early enteral feeding has been associated with necrotizing enterocolitis, whereas early feeding with colostrum and breast milk has reduced the incidence of spontaneous intestinal perforation.[13]

- Spontaneous intestinal perforation usually presents with acute abdominal distension and bluish-black discoloration of the abdomen, whereas necrotizing enterocolitis usually presents will initial signs such as emesis, bloody stools, and abdominal wall edema, crepitus, and induration.

- While necrotizing enterocolitis usually presents with radiographic findings such as pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous air, thickening of the intestinal wall, and fixed dilated small bowel loops, the typical radiographic finding of spontaneous intestinal perforation involves pneumoperitoneum.

- On histopathologic exam, coagulative necrosis is observed in cases of necrotizing enterocolitis, whereas isolated hemorrhagic necrosis is the typical finding in spontaneous intestinal perforation.

- Necrotizing enterocolitis involves a variable degree of inflammation and ischemia of the bowel with extensive peritoneal contamination and bacterial translocation, whereas spontaneous intestinal perforation involves a focal area of perforation with normal-appearing proximal and distal intestines.[27]

Prognosis

Spontaneous intestinal perforation is associated with increased mortality and morbidity. The mortality rate is approximately 20 to 40%. Prognosis depends on the severity and extent of the spontaneous intestinal perforation.[28] Concomitant sepsis is associated with a worse prognosis. Advances in neonatal care and support with parenteral nutrition and antibiotics have tremendously improved the survival of infants with spontaneous intestinal perforation.[29] However, the morbidity in the survivors is often associated with surgical procedures, prolonged need for total parenteral nutrition, prolonged hospitalization, and prolonged need for mechanical ventilation.[30]

Infants with spontaneous intestinal perforation are at an increased risk for developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia, intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, and growth failure. These infants are also at risk of neurodevelopmental impairment.[31][10][32][4]

Complications

Complications of spontaneous intestinal perforation include surgical complications as well as prolonged hospitalization and treatments, including parenteral nutrition. Post-operative adhesions and scarring may lead to stricture and obstruction. Other complications include short bowel syndrome, cholestasis, intestinal failure, nutritional deficiencies, and associated failure to thrive.[33][32]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Following surgery for spontaneous intestinal perforation, infants should receive intravenous antibiotics and total parenteral nutrition. The stoma site should be monitored. Intensive medical care, including monitoring intake and output, checking and correcting electrolyte abnormalities, preventing anemia, etc., should be continued post-operatively. Most infants may also require ventilatory support. The introduction of enteral feeds after the surgery should be decided by the primary team and the surgical team based on the postoperative course.[34]

Consultations

Often, the infants are in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), and the following consultations are recommended:

- Pediatric surgery

- Nutrition

- Pediatric GI- for complications associated with prolonged parenteral nutrition

Deterrence and Patient Education

A deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of spontaneous intestinal perforation may lead to better preventative strategies. Antenatal and postnatal conditions which cause hypoxemia and decreased intestinal blood flow have been implicated as risk factors for developing spontaneous intestinal perforation. Medications such as early indomethacin and early postnatal glucocorticoids must be cautiously used for infants with such risk factors. Enteral feeding, especially breast milk, and colostrum care should be encouraged from birth.

Pearls and Other Issues

Spontaneous intestinal perforation is potentially fatal and may present with various signs and symptoms. Timely diagnosis is of utmost importance. The most important diagnostic study is the abdominal plain film radiographs, showing free air in the abdomen. Pediatric surgery should be involved for further management.

The initial management includes cessation of enteral feedings, gastric decompression with a nasogastric tube, intravenous antibiotics, and total parenteral nutrition. Surgical management includes primary peritoneal drainage and laparotomy. Postoperative care includes parenteral nutrition and stoma care. Many of these patients require NICU hospitalization for a prolonged period.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of spontaneous intestinal perforation require an interprofessional team approach. Diagnosis is based on clinical and radiographic findings. The initial evaluation is often by a neonatologist. Radiologists play a critical role in determining the presence of free air, which is pathognomonic for spontaneous intestinal perforation.

Once the diagnosis is made, the initiation of treatment requires the involvement of a pediatric surgical team. Establishing vascular access for antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, and lab analysis is crucial. A nutritionist must be involved when initiating total parenteral nutrition, and a pediatric gastroenterologist may have to be consulted later in the hospital to manage complications related to prolonged TPN. An interprofessional team approach that includes open communication channels between all team members and meticulous documentation of all interventions and findings is vital to improving the outcomes for the patients. [Level 5]