Introduction

Hearing loss is common in the United States, with approximately 13% of people over 12 years of age reported experiencing hearing loss in both ears on clinical testing.[1] Therefore, it is vital that audiologists can accurately measure patients' hearing to help provide the best management for hearing loss. If a hearing loss is detected, it is also important to understand whether it is a conductive or sensorineural hearing loss, as both possible underlying pathophysiology and management options differ.

A pure tone audiogram is a behavioral test of hearing, where a tone at a specific frequency is presented to the test ear by over-ear headphones or inserted earphones. The loudness of the tone is altered to find the quietest tone in decibels (dB) which can be heard 50% of the time, which is termed the threshold.[2] This process is then repeated for each sound frequency being tested. Typically 6 to 8 frequencies are tested, between 250 Hz and 8000 Hz, and the process is repeated for the other ear.

Clinical masking in audiology refers to introducing noise to the non-test ear during a pure-tone audiogram. This aims to ensure that the test ear hears the presented tone and is not cross-heard by the non-test ear. Cross-hearing occurs when a tone presented to the test ear overcomes interaural attenuation, which refers to the loss of acoustic energy as sound waves travel transcranially to the contralateral ear. The presented tone can then be perceived by the cochlea of the non-test ear and give rise to false-positive results. This occurs less readily when testing air conduction through insert earphones than supra-aural earphones, as insert earphones cause increased interaural attenuation.[3]

Therefore, clinical masking is required when the difference in hearing thresholds between the ears is greater than the interaural attenuation. More specifically, for air conduction testing, masking is employed when the difference between unmasked thresholds in both ears is greater than 40 dB (or 55 dB when using insert earphones), which is thought to be the minimum interaural attenuation for pure tones.[4] There is negligible interaural attenuation for bone conduction, which is assumed to be 0 dB for bone conduction testing, as sound travels via bone conduction through the skull to both cochleae.[5] There are 3 key situations where masking is required, termed rules of masking. These are detailed below.

Procedures

When non-masked hearing thresholds are established, and it has been determined that masking should be employed, the effective masking threshold should be obtained for the non-test ear.[6] This refers to how loud the masking noise must be to prevent cross-hearing by the non-test ear.

Several methods are used to determine the effective masking level for each frequency being tested, often with an initial masking tone loudness similar to the non-masked air conduction threshold used. This is played into the non-test ear via over-ear headphones or inserted earphones. In contrast, the new accurate threshold of the test ear is determined using the same process described above for a pure tone audiogram. The masking noise in the non-test ear is increased in intervals, with further testing of the pure tone thresholds in the test ear with each new interval until a plateau threshold is found. This is the level at which the masking noise is loud enough to avoid cross-hearing the pure tone by the non-test ear but not loud enough to cause the masking noise in the test ear, known as over-masking.[7][8]

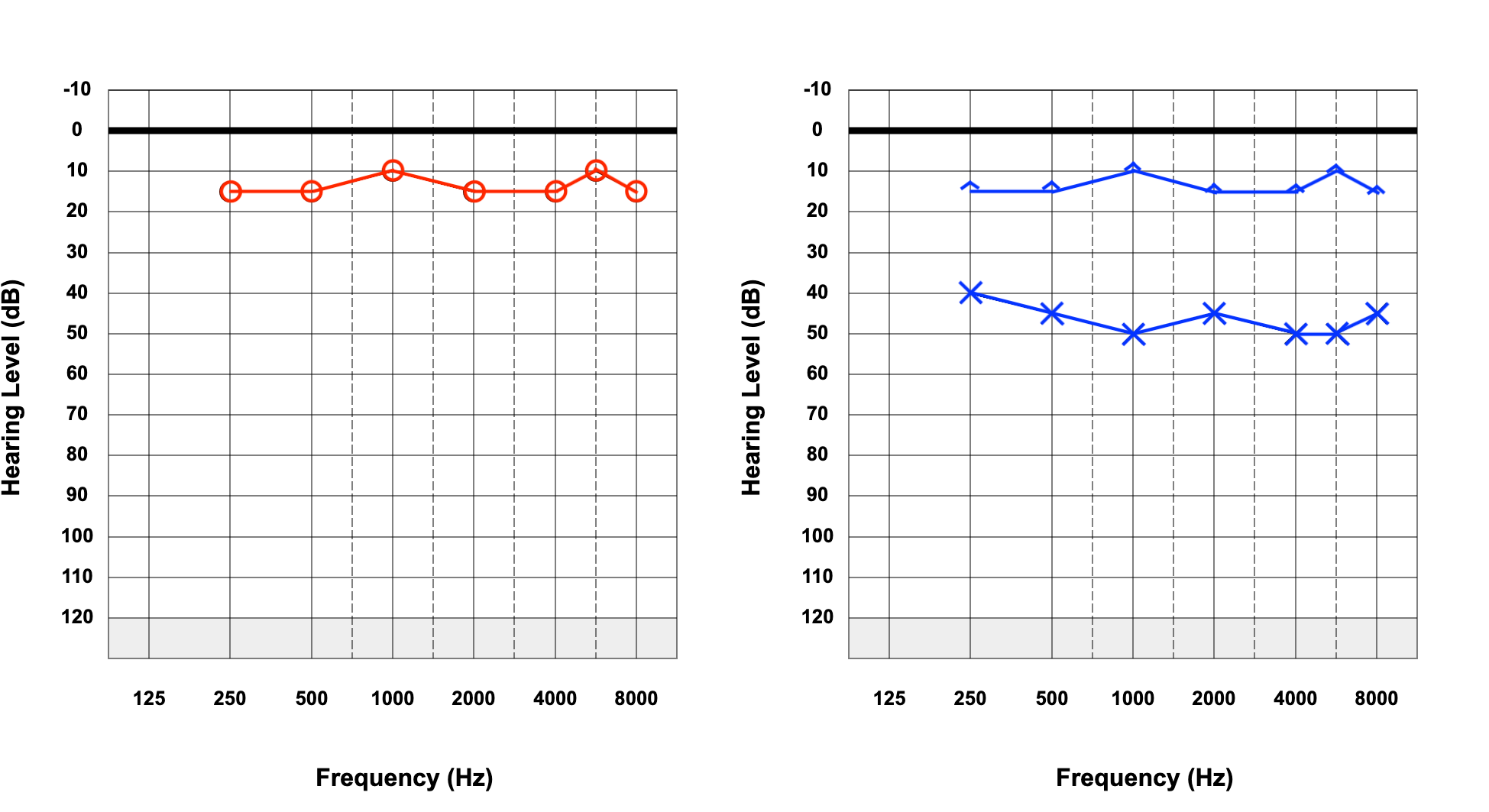

Once a new accurate threshold has been found for each frequency in both ears, these results are plotted onto an audiogram, as seen below. An audiogram is a graphical representation of hearing thresholds in both ears at specific frequencies. Different symbols represent different aspects of the audiogram, including masked and non-masked air conduction and bone conduction, so the person interpreting the audiogram can establish whether masking has been employed and whether there is an air-bone gap, inferring a conductive hearing loss. Examples of audiograms can be seen below.

Indications

Three rules of masking indicate when masking should be employed, as discussed by Studebaker in 1964.[9] Each rule should be considered for both ears and each frequency.

Rule 1

This rule applies when there is a difference in non-masked air conduction between each ear, equal to or greater than 40dB (55dB if using inserted earphones).

Rule 2

When there is a difference between the non-masked bone conduction threshold and the air conduction threshold of either ear is greater than 10dB.

Rule 3

When rule 1 has not been applied and where the bone conduction threshold of one ear is better by 40dB (or 55dB if using insert earphones) than the air conduction threshold of the contralateral ear.

Normal and Critical Findings

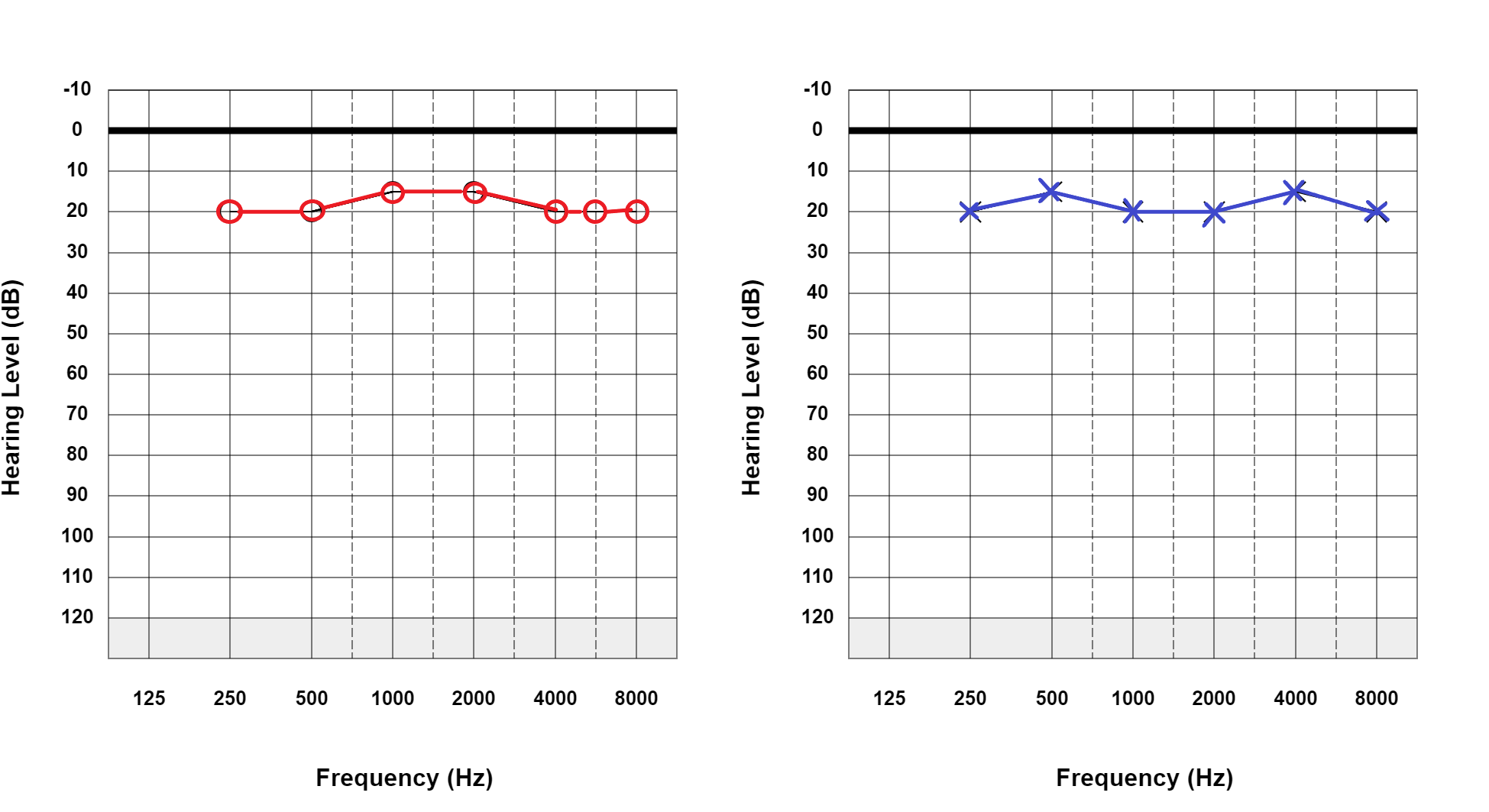

A normal audiogram does not satisfy any of the above rules and does not require masking. An example of a normal audiogram, with the red circles correlating to non-masked air conduction in the right ear and the blue crosses correlating to non-masked air conduction in the left ear, is illustrated below (see Figure. Normal Hearing Thresholds). This does not require masking because each ear has no significant difference in non-masked air conduction. Equally, because the hearing thresholds are normal, bone conduction does not need to be performed as there is no concern about conductive hearing loss.

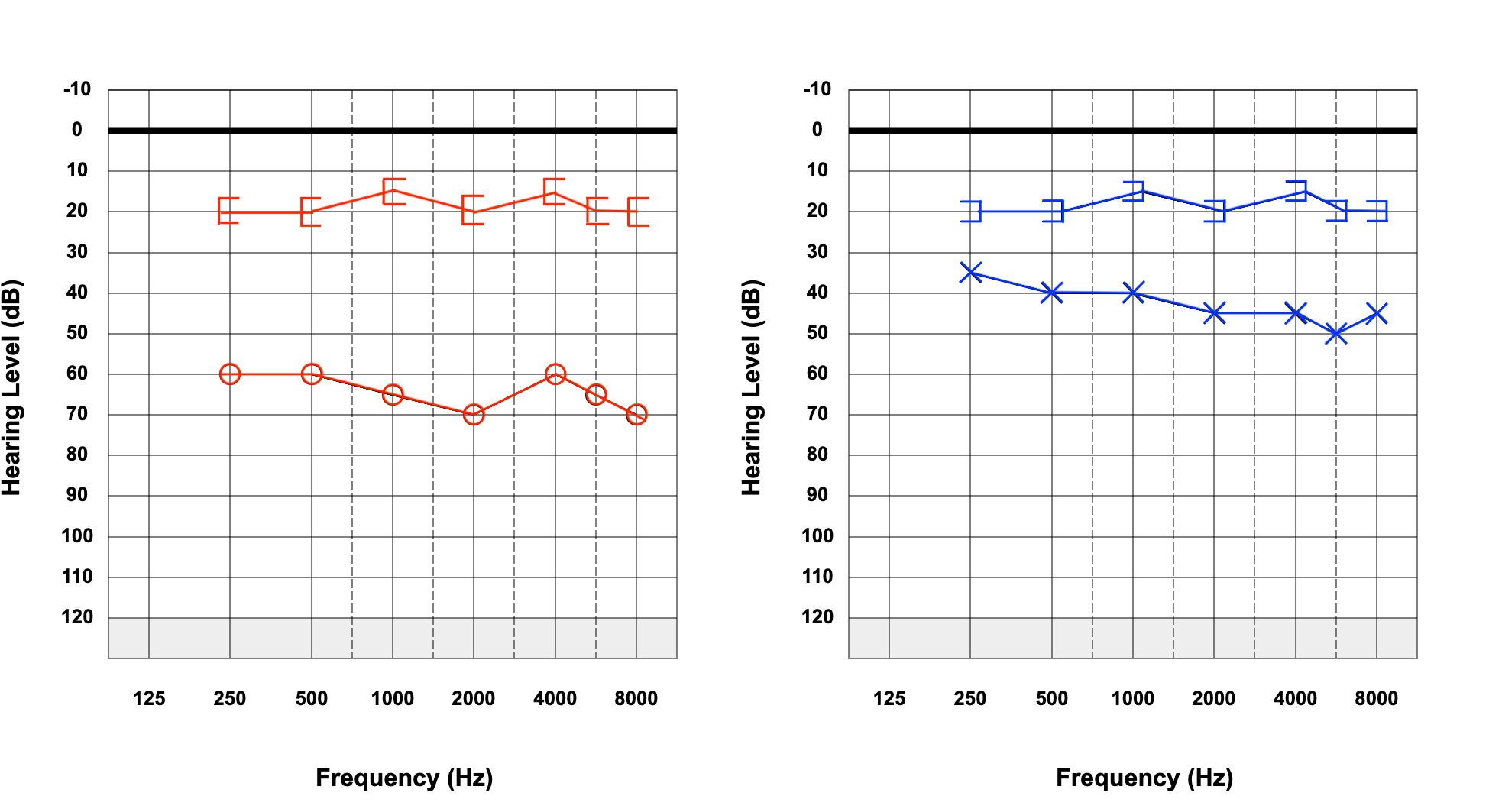

In the next figure, the blue circumflex accents represent non-masked bone conduction (see Figure. Bilateral Conductive Hearing Loss). There is a difference between the non-masked bone conduction thresholds and the non-masked air conduction thresholds on the left. This satisfies rule 2 and therefore requires masking; this is because without masking, it is not possible to establish whether this is a conductive or sensorineural hearing loss, as clinically, it is impossible to ascertain whether the non-masked bone conduction pertains to the left or right cochlea. To determine whether the hearing loss is sensorineural or conductive, masking of the right (non-test) ear is required with re-testing of the bone conduction in the left (test) ear.

If the hearing loss is sensorineural, the masked bone thresholds lie at the same thresholds as the non-masked air on that side. In contrast, if the hearing loss is conductive, the masked bone conduction thresholds mirror the non-masked bone conduction, as seen in another figure (see Figure. Left-Sided Conductive Hearing Loss). Here the masked bone conduction has replaced the non-masked bone conduction on the image and is demonstrated with square brackets. Following masking, the audiogram demonstrates that there is left-sided conductive hearing loss.

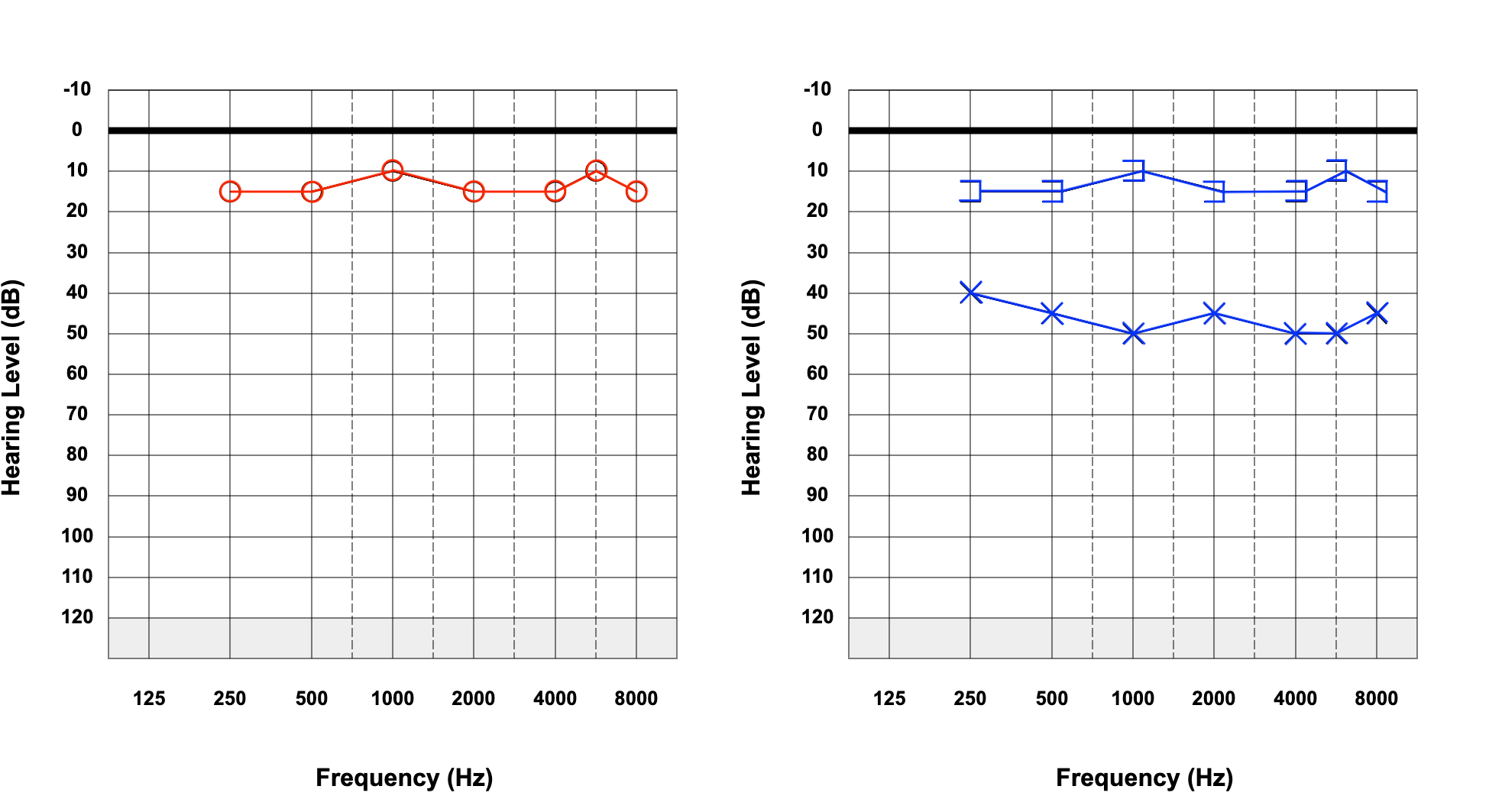

The next figure shows a right-sided hearing loss, with a difference greater than 40 dB between the right and left ear in non-masked air conduction (see Figure. Right-Sided Hearing Loss). This, therefore, satisfies rule 1 and requires masking. This is because without masking, it is impossible to identify whether the tones presented to the right ear are being heard by the right cochlea or being cross-heard by the left cochlea, as with a greater than 40 dB difference between each ear, the interaural attenuation may be exceeded when testing the right ear.

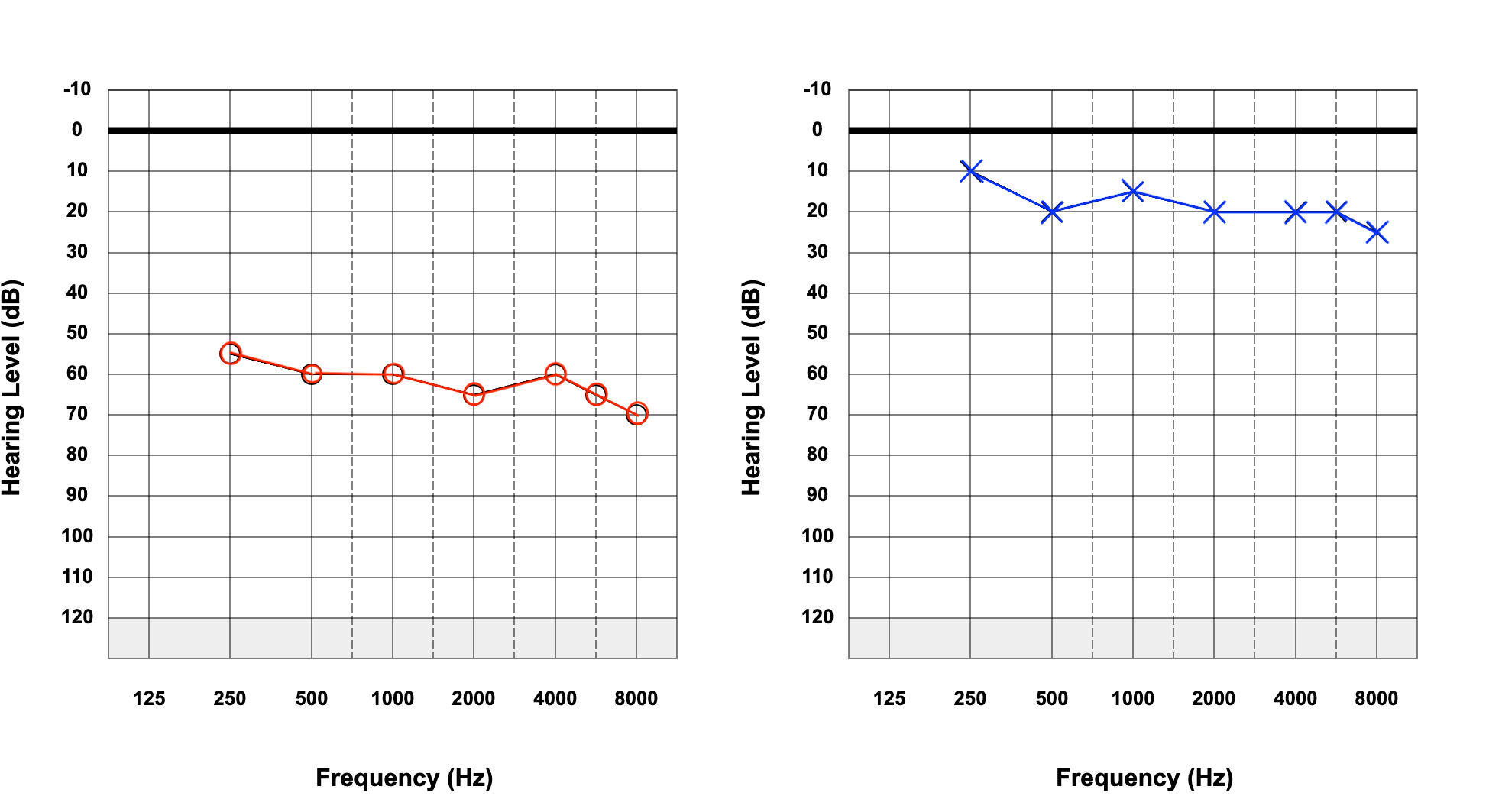

The last figure shows an audiogram of a patient with reduced hearing bilaterally and worse on the right (see Figure. Left-Sided Hearing Loss). Initially, rule 1 was not applied, as the difference between non-masked bones does not exceed 40 dB. However, rule 2 was applied as there was a greater than 10dB difference between the air conduction and non-masked bone conduction. Therefore the bone conduction was masked on both sides, revealing a bilateral conductive hearing loss. However, once masking of the bone conduction has been applied, it is evident that there is now a difference of at least 40 dB between the air conduction thresholds in the right ear and bone conduction thresholds in the left ear. Therefore rule 3 applies, and masking should be performed for air conduction.

Complications

Masking Dilemma

In situations with a sizeable conductive component in both ears, it may not be possible to mask effectively at all. An example of this is as follows:

During an audiometric assessment, air conduction thresholds receive values of 70 to 105 dB across all frequencies in both ears. On continuing to test bone conduction testing, non-masked bone conduction testing responses receive values of 15 to 20 dB across all frequencies. Here, the difference between air conduction and bone conduction is greater than 55 dB (interaural attenuation); therefore, masking is required.

As a procedure, the masking noise to the nontested ear may be set at 80 dB, and a tone presented (via bone) to the test ear at 15 dB. If there is no response, the tone increases (via bone) to the test ear to 20 dB. If there is a response at this level, the masking noise is increased in the non-test ear to 85 dB, and the tone is then re-presented to the test ear. If there is no response at this level, the tone of the test ear is then increased (via bone) to 25 dB. If, at this level, there is a response, then the masking noise presented to the non-test ear is increased to 90 dB. If, at this level, there is no response, the pattern may continue without ever reaching a plateau or receiving true masked levels. The masking noise crosses over to the test ear as the test tone increases, creating a masking dilemma.

In this circumstance, the unmasked responses are labeled with an asterisk, and it is stated that masking is not possible without over-masking. This must be confirmed at all frequencies.

Patient Safety and Education

The potential causes of hearing loss are varied, and their management options correspondingly so. Many common causes of hearing impairment, such as age-related hearing loss, are considered benign. However, as stated earlier, even benign hearing loss can contribute to social isolation and depression. Therefore patients should be encouraged to seek help regarding hearing loss if they or a relative notice that their hearing is declining. Patients presenting with hearing loss should undergo appropriate and thorough clinical assessment, including a pure tone audiogram, to determine whether further investigations are required.

Clinical Significance

It is essential to distinguish between conductive and sensorineural hearing loss, which can help establish the associated pathologies. Conductive hearing loss occurs when sound waves are inhibited from reaching the cochlea, primarily due to mechanical pathology of the pinna, ear canal, or middle ear. The causes vary from conditions affecting the pinna, such as microtia, and canal conditions, including cerumen impaction and otitis externa, to middle ear pathologies, such as serous otitis media, cholesteatoma, or ossicular disruption. The management options vary considerably depending on the underlying pathology, so patients must receive a thorough clinical assessment.[10]

Sensorineural hearing loss occurs due to pathology of the inner ear or the cochlear nerve from the inner ear to the auditory cortex.[11] The most common cause of sensorineural hearing loss is presbycusis, or age-related hearing loss, with the vast majority of the population over 70 years experiencing a degree of hearing impairment.[12]

Presbyacusis typically causes high-frequency hearing loss, and patients may struggle to hear high-pitched noises and alarms. Hearing loss is thought to be related to depression and cognitive decline in older adults. Awareness, assessment, and management of hearing loss with amplification devices are important, with sound amplification being shown to positively impact the quality of life.[13]

Other causes of sensorineural hearing loss include noise-induced hearing loss, which typically shows a drop at the 4 kHz frequency that may be detected on an audiogram. Rarer but more serious causes of hearing impairment, such as vestibular schwannoma, a benign tumor arising from the Schwann cells of the vestibular nerve, should be excluded if unilateral hearing loss is detected.

Accurate and appropriately masked, pure-tone audiograms are key to the overall clinical assessment of individuals experiencing hearing loss. A single pure-tone audiogram should be validated, meaning the results are analyzed and should be consistent with the clinical history, examination findings, immittance (tympanometry), and speech audiometry. Inconsistent results may highlight the need for further investigation, with repeated audiological testing, to ensure the accuracy of findings.