Continuing Education Activity

Retrobulbar hematoma is the phenomenon of blood collecting in the retrobulbar space behind the globe. Although not common, it is a serious condition that can lead to blindness. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of retrobulbar hematoma and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Determine the etiology of retrobulbar hematoma.

Identify the pathophysiology of retrobulbar hematoma.

Assess the typical presentation of a patient with retrobulbar hematoma.

Communicate the management considerations for patients with retrobulbar hematoma by an interprofessional team.

Introduction

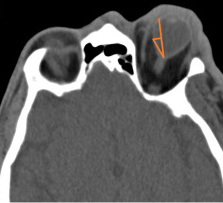

Retrobulbar hematoma (RBH) is a rare yet sight-threatening diagnosis.[1] Although mild cases may occur, a devastating consequence is orbital compartment syndrome, which can potentially lead to complete vision loss if not treated promptly. The definitive management is lateral orbital canthotomy and cantholysis, which can be vision-saving (See Image. Retrobulbar Hematoma).

Etiology

The development of a retrobulbar hematoma is most commonly associated with trauma, especially orbital floor fractures. However, a retrobulbar hematoma can also develop iatrogenically following sinus or ocular surgery. The incidence of retrobulbar hematoma secondary to these etiologies is very low. For example, the incidence of RBH after retrobulbar or peribulbar injection, zygomatic fracture repair, and blepharoplasty is 2%, 0.3%, and 0.055%, respectively.[2]

Rarely can a retrobulbar hematoma develop from Valsalva maneuvers in the context of anticoagulation. One case report describes a 31-year-old female who developed a headache and blurry vision after sneezing and was found to have a spontaneous retrobulbar hematoma. Other etiologies include vascular anomalies, coagulopathies, and uncontrolled hypertension.[3]

Epidemiology

The incidence of retrobulbar hematoma varies depending on the etiology and can range from less than 1% (post-surgical) to 4% (trauma). One study, comprised of 1,386 patients with facial trauma at a tertiary care trauma center, reported the incidence of RBH to be 3.6%. The incidence of permanent blindness in this population was 0.14%.[4]

Another study, which included 426 patients who underwent orbital wall fracture repair, reported an incidence of 1.2% for post-operative RBH. In this case series, the patients who developed RBH retained their normal visual acuity. Other incidence rates reported in the literature for RBH are 0.6% and 0.055% following orbital reconstruction and blepharoplasty, respectively.[5]

Pathophysiology

The defining pathophysiology of a retrobulbar hematoma is blood collecting in the retrobulbar space, which, as its name implies, is posterior to the globe. Although a mild fluid collection in orbit is tolerable, rapid hemorrhaging is not well compensated. As blood accumulates in this confined space, intraorbital pressure rapidly rises, causing increased venous pooling and a corresponding increase in intraocular pressure (IOP), decreased arterial flow, and essentially an orbital compartment syndrome.[6]

The increase in orbital pressure also results in a forward globe displacement and stretching of the optic nerve, known as proptosis (see Image. Retrobulbar Hematoma With Proptosis Noted on Computed Tomography). Furthermore, perfusion to the intraocular structures is compromised if the orbital pressure exceeds the central retinal artery pressure.[7] Elevated intraocular pressure lasting 60 to 100 minutes can cause permanent vision loss.[8]

History and Physical

Upon presentation, patients may very likely report a history of trauma. Care should be taken to elicit the mechanism of injury to assess for more emergent diagnoses, such as penetrating or perforating ocular trauma and possible globe rupture. Patients may complain of diplopia, headache, nausea, and vomiting. Some common signs and symptoms are eye pain, periorbital ecchymosis, decreased visual acuity, elevated IOP, a tense and progressive proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, and optic disc swelling.[1] A thorough ophthalmic exam should be completed. Visual acuity should be assessed for the right and left eye separately. One should check direct and indirect pupillary responses to light with careful attention to the presence or absence of a relative afferent pupillary defect. Extra-ocular movements should be assessed, as a restriction in motility can be a concern for the orbit.[3]

Intraocular pressure is an essential part of the physical exam. Although orbital pressure is not commonly measured directly in the clinical setting as it requires manometry, elevated IOP (normal range between 8 and 21 mmHg) and proptosis correlate well with orbital compartment pressure and are sufficient to indicate an impending orbital compartment syndrome.[9]

Patients can sometimes be unconscious or uncooperative, hindering the physician from obtaining a complete history and physical examination. Although multiple traumatic injuries and altered consciousness can make it challenging to evaluate a retrobulbar hematoma, it is imperative to obtain as much information as possible to gauge the severity of the trauma and obtain a rapid diagnosis.[2] Assessing for proptosis, resistance to retropulsion, pupillary responsiveness, IOP, and physical signs such as tense and edematous lids may indicate the presence of increased orbital pressure and aid in diagnosis. If the signs and symptoms of optic nerve ischemia from RBH are present and an IOP of 40 mmHg or more significant, immediate treatment should be initiated.[10]

Evaluation

Although radiographic testing can help to confirm a retrobulbar hematoma, the diagnosis is clinical.[5] RBH cases can range from mild, with no visual consequences, to severe, with orbital compartment syndrome (OCS). One retrospective chart review identified 32.3% of orbital wall fractures as having an associated retrobulbar hematoma via computed tomography (CT) scan. However, only 1.1% of these had orbital compartment syndrome requiring intervention.[11]

These results reinforce the importance of a thorough clinical exam. CT imaging can help visualize the extent of the hematoma and identify other associated injuries such as maxillofacial fractures, globe rupture, or intraocular foreign bodies. A CT scan may also reveal optic nerve tension or a distorted posterior globe. If a patient displays the signs and symptoms typical of optic nerve ischemia from RBH, however, radiographic imaging should be delayed in favor of prompt surgical intervention.

Treatment / Management

Once the diagnosis of a retrobulbar hematoma is confirmed, ophthalmology should be emergently consulted. However, the attending physician should not delay definitive management if optic nerve ischemia is suspected and intraocular pressure is greater than or equal to 40 mmHg.[7] Adequate anesthesia and antiemetics should be provided to aid in patient comfort and help prevent Valsalva maneuvers such as vomiting. A vital part of management is immediate orbital decompression with lateral orbital canthotomy and cantholysis (LOCC).

If possible, the surgical area should be prepped sterilely and cleaned with a povidone-iodine solution. Otherwise, saline irrigation may be sufficient in this emergent situation. Adequate anesthesia (1 to 2 milliliters of lidocaine 1% to 2% with epinephrine 1 to 100,00) should be administered into the cutaneous and deep tissues of the lateral canthus. Care should be taken to point the needle away from the globe when injecting. Next, the surgical area must be irrigated with sterile water to visualize important landmarks and flush away any foreign debris that may be present. Once there is adequate visualization, a hemostat can clamp horizontally across the lateral canthus for approximately 1 minute to aid in hemostasis and create a physical marker for cutting. After this, forceps should be used to raise the skin of the lower eyelid, and the lateral canthus should be cut 1 to 2 cm with Wescott scissors.[2]

Using scissors, the canthotomy exposes the lateral canthal tendon, which can also be identified with a strumming motion. The lateral canthal tendon can be further exposed by pulling down on the lateral lower lid with a hemostat or forceps. The tendon’s inferior crus should be cut by pointing the scissors anteroposteriorly. At this point, the lower eyelid should be completely mobile. LOCC helps alleviate the increased intraorbital pressure by freeing the lower eyelid from the orbit. The lateral canthal incision may need to be repaired at a later date.[7]

Mild cases of RBH without signs or symptoms of optic nerve compromise should be managed by observation or medical treatment.[10] Patients with RBH and no symptoms or elevated IOP can be monitored without intervention. IOP should be reassessed approximately 6 hours after the initial evaluation to ensure that there is no interim elevation that could signify a possible rebleed and indicate intervention. Alternative methods described in the literature for mild to moderate cases are direct needle aspiration of the hematoma and topical, oral, or intravenous medications such as beta-blockers (timolol maleate), steroids, and osmotic agents (mannitol).[5]

Reports have shown these to help lower intraocular pressure. Acetazolamide is another well-studied drug that can be administered orally or intravenously to lower IOP successfully.[12] Steroids may also protect against traumatic optic neuropathy. For all cases, appropriate follow-up with ophthalmology should be established. The frequency of monitoring depends on the patient’s severity of RBH.

In cases of postoperative RBH, prevention may be an effective form of management. Although specific risk factors for postoperative RBH have not been well-established in the literature, surgical optimization may be preventative. Case series have reported the development of RBH in patients using anticoagulants at the time of orbital wall fracture repair and orbitotomy. In light of this, informing patients to stop non-essential anticoagulants before surgical repair may be advisable. Perioperatively, adequate hemostasis should be achieved. The prevention of Valsalva maneuvers during the procedure may also be helpful.[5]

Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions to consider in patients with the signs and symptoms mentioned above, especially in the setting of trauma, include globe rupture and orbital fractures with entrapment.[1]

Prognosis

The prognosis for most patients who receive timely intervention is favorable. Most patients treated within 2 hours of presentation have been shown to attain a visual acuity better than 20/40. This is in contrast to those receiving treatment after 2 hours, only 25% of which may achieve 20/40 vision or better.[13] Case reports of patients with traumatic RBH and ‘No Light Perception’ vision have described the recovery of some vision after LOCC.[7]

Some factors that may point toward a poorer prognosis are a presenting visual acuity worse than 20/200, a relative afferent pupillary defect, an eyelid laceration, and increased time to treatment.[14] Retrobulbar hematoma associated with a traumatic etiology and a greater number of symptoms also has a poorer prognosis.[15]

With traumatic retrobulbar hemorrhage and acute vision loss, the risk of permanent blindness is 44 to 52%.[10] As stated earlier, the incidence of permanent visual loss from RBH is much lower for post-surgical etiologies.

Complications

Complications of LOCC include a persistently elevated IOP, which may indicate inadequate cantholysis. In this case, one should ensure that an adequate inferior cantholysis was performed.[6] Once this is ascertained, an additional cantholysis may still need to be performed on the superior crus of the lateral canthal tendon to achieve adequate orbital decompression. Other complications from performing a lateral orbital canthotomy include damage to nearby ocular structures, globe rupture, infection, bleeding, and eyelid malpositioning.[7] Loss of lower eyelid suspension can produce cosmetic concerns, which can be addressed non-urgently by ophthalmologists trained in oculoplastic surgery once the immediate threat of vision loss has subsided.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After a complete LOCC, visual acuity, IOP, pupillary function, and other signs of optic nerve ischemia should be reassessed. The patient may require adjuvant therapy with topical IOP-lowering drops or systemic agents. The surgical site should also be monitored at appropriate intervals for signs of infection. Topical ophthalmic antibiotic ointment (eg, erythromycin and bacitracin) should be applied to the surgical site.

Consultations

An ophthalmology consult is warranted in the evaluation and management of RBH. Other services may be required depending on the extent of the condition or associated injuries. Oral maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) or otolaryngology (ENT) should be consulted for orbital wall fractures as per the established trauma protocols of the treating facility.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated on the importance of prevention and ocular safety. Appropriate eye protection should be prioritized, especially in high-risk areas (construction, sports, military, etc). In appropriate situations, helmets, face shields, and safety goggles should be encouraged. Eye protection should especially be advocated for in monocular patients.

Pearls and Other Issues

Obtain ophthalmology consultation emergently, but do not delay definitive management if an orbital compartment syndrome from retrobulbar hematoma is suspected or confirmed.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although the development of a retrobulbar hematoma is rare, ocular trauma is fairly common and can have devastating consequences. The majority of these cases are present in the emergency room setting. The on-call ophthalmologist should be consulted immediately. However, rapidly deteriorating vision, signs and symptoms of orbital compartment syndrome, and the unavailability of timely ophthalmologic consultation should prompt treatment by the available physician.[7] Emergency room physicians should be equipped to perform an LOCC if necessary, improving outcomes for patients with clinically significant retrobulbar hematoma.

Studies have shown that further education is needed regarding lateral canthotomy and cantholysis performance. This is primarily due to the low frequency of RBH, which prevents emergency medicine physicians from having ample opportunity to perform this procedure. One study conducted in a level-1 trauma center in the United States revealed an average of only 5 lateral canthotomies per year.[16]

A 2019 prospective cohort study revealed that only 37.1% of non-ophthalmic emergency medicine physicians would perform a LOCC when necessary. An overwhelming 92.2% reported an unwillingness to perform a LOCC themselves due to inadequate training. This study underscores the need for collaborative training among emergency medicine physicians and ophthalmologists in this area. Using porcine models for LOCC practice has been documented as an excellent teaching method for residents.[10] Such training can be vital since irreversible vision loss can be prevented if LOCC is performed within 2 hours of patient presentation.[7][16]