Continuing Education Activity

Buccal fat pad removal is performed to close oroantral communications and for aesthetic recontouring of the face. This activity outlines and explains the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating buccal fat pad removal patients.

Objectives:

Evaluate the anatomy and physiology of the buccal fat pad.

Assess the indications for buccal fat pad removal.

Identify the most common complications associated with buccal fat pad removal.

Introduction

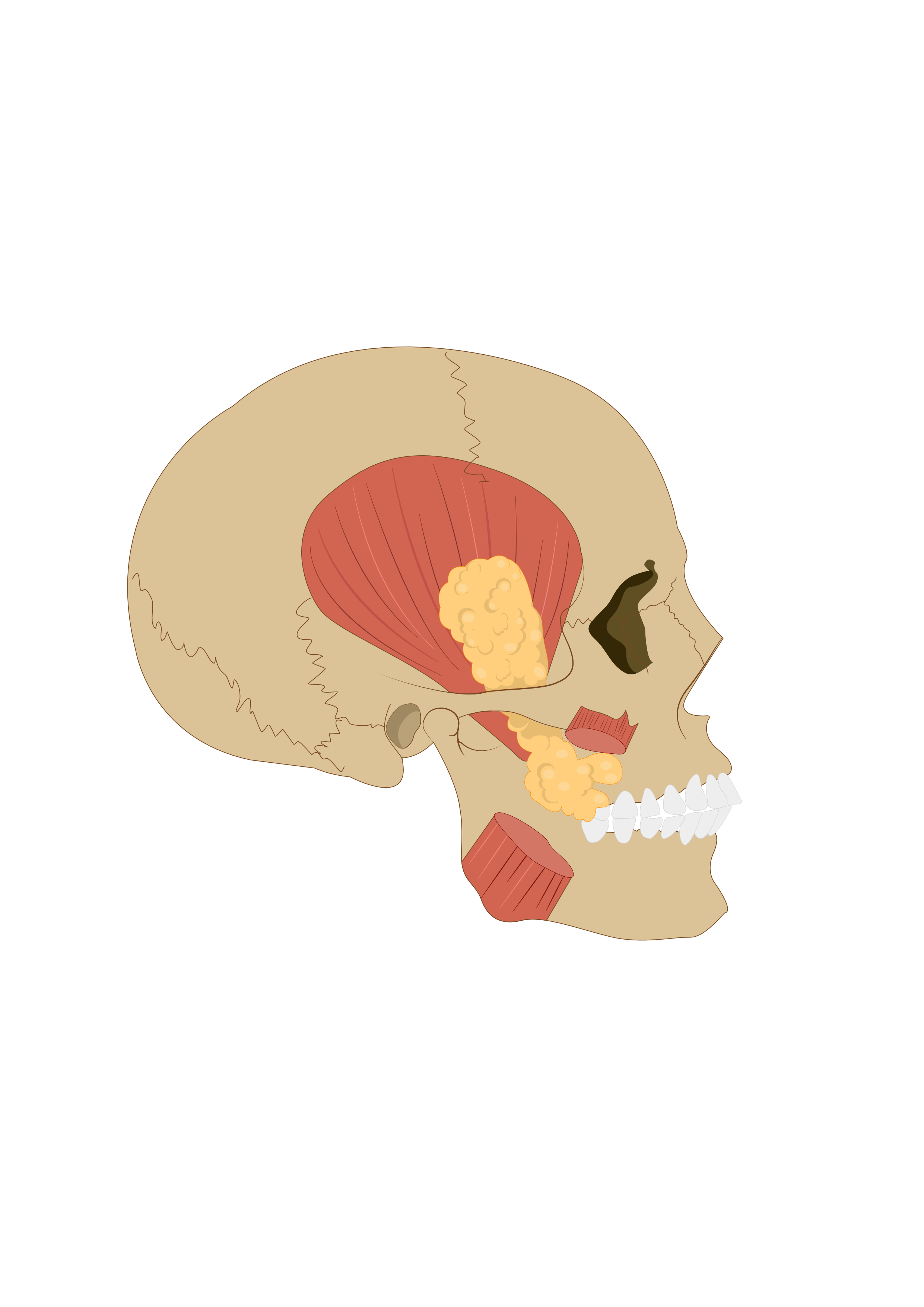

The buccal fat pad, also known as Bichat’s fat pad, is an important anatomical structure that contributes to facial aesthetics and facilitates movement of the facial muscles (see Image. Buccal Fat Pad). Many studies have researched the utility of the buccal fat pad in oral defect repair and trauma, as the buccal fat pad may be utilized as a pedicled autogenous graft for oroantral fistula repair. However, the buccal fat pad plays an important role in facial aesthetics and may be modified to enhance facial contour.[1] When indicated, the buccal fat pad’s removal enhances the zygomatic prominences and overall contour of the face. This topic discusses the anatomy and physiology of the BFP and the indications, techniques, and complications associated with removing the BFP to enhance facial aesthetics.[2]

Anatomy and Physiology

For centuries, anatomists have studied the complex nature of the fat pads of the face. Many functions are attributed to the buccal fat pad. It is a prominent structure in neonates and is thought to be utilized primarily to support the suckling function. As children age and begin chewing, the buccal fat pad facilitates the gliding function among the muscles of mastication. The buccal fat pad also serves as a cushion to protect neurovascular structures from external forces. These adipose structures also play an important role in facial aesthetics in people ranging from neonates to the elderly.[3] Anatomists have extensively researched the structure of the buccal fat pad for many years. Bichat first described it in 1802. It is thus referred to as the boule de Bichat in the non-English-speaking world.[4] Bichat’s fat pad is located between the anterior margin of the masseter and the buccinator, with the mean volumetric variation found to be 7.8 to 11.2 milliliters for males and 7.2 to 10.8mL for females with a mean thickness of 6 millimeters. Imaging studies demonstrate that the buccal fat pad grows significantly from ages 10 to 20, increasing from 4000 to 8000 cubic millimeters, then declining in size over the next 30 years to an average volume of 7000 cubic millimeters.[5] It has a complex anatomical structure closely related to the facial nerve, parotid duct, and masticatory muscles.[6] A sound understanding of the boundaries and contents of the buccal fat pad enables the operator to manipulate its structure safely in aesthetic and reconstructive procedures.

After its initial anatomical description by Bichat, it has since been described by several anatomists, including Gaughran in 1957, Dubin in 1989, and most recently Zhang in 2001.[4] Its structure is commonly described as a centrally located body with 4 extensions or 3 separate lobes. Zhang, in 2001, performed a cadaveric study and confirmed that the buccal fat pad consists of 3 separate lobes: the anterior, intermediate, and posterior. The posterior lobe is subdivided into the temporal, pterygoid, pterygopalatine, and buccal extensions.[7] The buccal fat pad is confined by the buccinator muscle medially. Anterolaterally, it is confined by the muscles of facial expression and the deep cervical fascia. Posteriorly, it is confined to the masticator space. Independent membranes encapsulate the buccal fat pad's anterior, intermediate, and posterior lobes. Ligaments to the maxilla, posterior zygoma, temporalis tendon, buccinator membrane, and rim of the infraorbital fissure fixate the buccal fat pad. The ligaments serve as conduits for the entry of multiple vessels that provide a rich blood supply to the different lobes of the buccal fat pad.[8]

The anterior lobe of the BFP is a triangular mass that lies inferiorly to the zygoma and is confined to the buccal space. Its anterior vertex extends to the front border of the buccinator, where it meets the orbicularis oris. The superior vertex of the anterior lobe extends to the inferior margin of the orbicularis oculi, where it enters the infraorbital foramen and encapsulates the infraorbital vessels. The facial artery borders the front of the anterior lobe. The buccal branches of the facial nerve either overlie or lie within the anterior lobe (as well as the buccal extension of the posterior lobe). The parotid and facial vein duct passes through the anterior lobe. The anterior lobe extends posteriorly and joins with the intermediate and posterior lobes via loose connective tissue. The intermediate lobe lies lateral to the mid-maxilla and joins the anterior and posterior lobes. In adults, it is a membranous structure composed of thin, fat tissue that runs superiorly to inferiorly, segregating the anterior and posterior lobes. It is not always identified in adults, but it is a more substantial fatty mass in children.[7] The posterior lobe of the buccal fat pad, synonymous with the body, is the most substantial. It is confined to the masticatory space. It consists of 4 extensions: the buccal, pterygoid, pterygopalatine, and temporal extensions. The buccal extension and body account for roughly 50 percent of the buccal fat pad volume.[6] The posterior lobe or body spans superiorly to the inferior orbital fissure, surrounds the temporalis muscle, spans inferiorly to the superior mandibular body, and courses posteriorly to the anterior ramus and tendon of the temporalis.

The buccal extension lies inferior to Stenson’s duct, and it is the most superficial process and is the portion removed during buccal fat pad resection. The pterygopalatine extension lies within the pterygopalatine fossa and surrounds the pterygopalatine vessels. It also runs superiorly to the infraorbital fissure, encapsulates the infraorbital vessels, and fuses to the anterior lobe capsule.[9] The pterygoid extension is located within the pterygomandibular space and houses the mandibular neurovascular bundle, which includes the lingual nerve. It rests on the lateral aspect of the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles. The temporal extension of the buccal fat pad spans deep to the temporalis. It is important to understand that both a superficial and deep body of fat is present concerning the temporalis. The deep portion runs in continuity to the buccal fat pad. The superficial temporal fat pad is separate from the buccal fat pad and has a distinct vascular supply.[6]

Indications

There are several clinical indications for accessing the buccal fat pad. It may be utilized for close oroantral communications. Oroantral communication is communication between the maxillary sinus and the oral cavity. It may occur during the extraction of maxillary premolars and molars, secondary to dental infections, radiation therapy, osteomyelitis, or trauma.[10] An OAC of 2 millimeters or less usually closes spontaneously; however, if the defect is greater than 3 to 4 mm, the surgical closure of the defect is indicated. Accessing and advancing the buccal fat pad is a means of closing an oroantral communication. Perhaps the most recent interest in the buccal fat pad is utilized to reshape the facial contours, providing a more aesthetic facial architecture.[11] The ideal aesthetic surgical candidate for buccal fat pad removal has prominent zygomatic cheekbones that are masked due to pronounced cheeks. These patients lack an angular appearance to the face; buccal fat pad removal reduces cheek fullness and highlights their pronounced zygomatic bone. Malar hypoplasia is not an indication of buccal fat pad removal. Buccal fat pad removal in these patients results in a hollowed appearance of their cheeks. For this reason, it is important to understand that buccal fat pad removal is not a substitute for malar augmentation.[6]

Technique or Treatment

The safest method for accessing and removing the buccal fat pad for facial aesthetics is intraoral access. The Stenson duct is the key structure to identify before creating an incision, which opens the parotid gland into the oral cavity. The incision may be created superior to the duct in the maxillary vestibule or inferior to the parotid duct at approximately the level of occlusion. This approach provides access to the buccal extension of the posterior lobe. The buccal fat pad may be accessed either inferior to or superior to Stenson’s duct for aesthetic purposes. The preferred method at the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Program at Madigan Army Medical Center is to access the buccal fat pad inferior to Stenson’s duct. A Minnesota Retractor is utilized to retract the cheek, and local anesthesia is first injected into the buccal mucosa; Stenson’s duct is positively identified, and a shallow 1.5 cm horizontal incision is placed with a 15-blade in the buccal mucosa midway between the occlusal plane and Stenson’s duct. At the time of incision, the opposite hand is utilized extra-orally to apply pressure on the contents of the buccal fat pad to facilitate exposure into the oral cavity. Hemostats are then utilized to bluntly dissect through the buccinator muscle and access the buccal fat pad.[12] The narrow buccal space is accessed, and the yellow fat pad is exposed. 3 to 5 cc of the fat pad is gently teased out of the buccal space. Hemostats are then used to clamp the fat pad and the mucosa level, while 15-blade or surgical scissors are utilized to excise the fat pad. The mucosa is then reapproximated with 2 single 4.0 interrupted absorbable sutures. It is crucial not to apply excessive traction on the buccal fat pad during removal with excessive pulling and only to resect the portion of fat that protrudes passively into the oral cavity.[13]

Complications

Buccal fat pad reduction is generally considered a safe and relatively simple procedure. Complications related to bichectomy are rare but are clinically significant when they do occur. The buccal fat pad is closely positioned to multiple vessels, the facial nerve, and the parotid duct. Removal of the BFP can result in damage to these vital structures. Complication rates are between 8.45% and 18%. Complications may result in parotid duct injury, hematoma, trismus, neuromotor deficits, and infection. A case presentation in The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery discussed 2 cases of complications after removing the buccal fat pad. The first case report describes a patient who presented to the emergency dept 5 days post-operatively with facial asymmetry. The patient was initially admitted and treated for an infection. However, the patient was re-presented with increasing pain and edema, requiring further investigation. The patient was found to have an accumulation of saliva in her buccal mucosa from obstruction of the Stenson duct due to iatrogenic damage of the duct. The patient was admitted for an additional 7 days. During admission, the patient received conservative therapy and multiple drainages of the right buccal mucosa. The patient re-established good salivary drainage and was discharged home.[14]

The second case report describes a patient who presented hours after buccal fat pad removal with severe facial pain and edema. The patient also had significant ecchymosis of the infra and periorbital regions. The patient's clinical presentation was due to active bleeding from the sphenopalatine artery, and compression and attempts to locate and ligate the vessel were unsuccessful. The patient was emergently transported to the operating room, where the interventional radiology team performed angiographic embolization. Severe bleeding due to vessel damage during buccal fat pad removal is a rare complication likely resulting from either a vessel traction injury or deep dissection of the oral space. Knowledge of the buccal fat pad and its related vital structures is fundamental to mitigating complications associated with buccal fat pad reduction. Appropriate informed consent is critical as even when demonstrating sound surgical technique, complications can occur due to the intimate association of the buccal fat pad with vital structures.[15]

Clinical Significance

Buccal fat pad removal is not the primary focus of aesthetic surgery; rather, it is a relatively minor procedure used in conjunction with larger procedures. Buccal fat pad removal thins the face and enhances the aesthetics of the upper cheek area. The procedure is commonly performed to reduce the submalar prominence.[5]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Clear communication among the team when performing procedures is key for the entire oral and maxillofacial surgery team. The buccal fat pad has long been considered a nuisance in many surgeries as its discovery is not usually intentional. Clear communication with surgical assistants is critical so as not to dislodge the buccal fat pad with overzealous suctioning high into the maxillary vestibule.[16]