Continuing Education Activity

Neovascular glaucoma (NVG) is characterized by the formation of new blood vessels over the iris and the angle of the anterior chamber. These new blood vessels form as a result of ocular ischemia. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), ischemic central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), and ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS) contribute to the majority of cases of NVG. The prevalence of NVG is on the rise due to an increasing prevalence of diabetes. NVG is a potentially blinding disease. Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are crucial aspects of NVG management. This activity describes the systemic and ophthalmic evaluation and treatment of NVG and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and managing care for patients with NVG.

Objectives:

Identify the epidemiology of neovascular glaucoma.

Determine the ophthalmic and systemic evaluation of neovascular glaucoma.

Assess the management options available for neovascular glaucoma.

Communicate interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance studies on neovascular glaucoma and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Neovascular glaucoma (NVG) is a secondary glaucoma characterized by new vessels on the iris and angle of the anterior chamber (AC). It is usually associated with a poor visual prognosis.[1][2][3] The mechanism of anterior segment neovascularization is ischemia of the posterior segment of the eye resulting from several ophthalmic and systemic etiologies.[3][4] The most common etiologies include proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), and ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS).[5]

In 1906, Coats described new vessels over the iris (rubeosis iridis) in a patient with CRVO. Due to the formation of new vessels in the anterior segment of the eye, the rise in intraocular pressure, and the connective tissue growth, the term NVG was coined by Weiss et al.[6] Some other synonyms used for NVG are hemorrhagic glaucoma, thrombotic glaucoma, and congestive glaucoma.[2]

NVG is usually refractory to treatments, and visual morbidity is significant for the patient. There are increasing numbers of NVG cases, probably due to the rise in the number of patients with diabetes and other non-communicable diseases, which are risk factors for retinovascular entities such as diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusions, and ocular ischemic syndromes. Knowledge of the evaluation and management of NVG is crucial for all ophthalmologists.

Etiology

The inciting factor for NVG is retinal or ocular ischemia.[3][4] All the causes of NVG share the common mechanism of retinal ischemia, which results in the development of new vessels over the iris and the angle of the anterior chamber. The etiological conditions for NVG can be described under the following headings:[4]

|

Retinal Ischemic Disease

|

Diabetic retinopathy

Central retinal vein occlusion

Central retinal artery occlusion

Branch retinal vein occlusion

Branch retinal artery occlusion

Retinal detachment

Retinopathy of prematurity

Sickle cell retinopathy

Hemorrhagic retinal disorders

Coat disease

Eales disease

Leber congenital amaurosis

Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous

Retinoschisis

Syphilitic posterior uveitis and vasculitis

Inherited vitreoretinal degenerations

Optic nerve glioma and resulting venous stasis retinopathy

|

|

Irradiation

|

Photo-radiation

External beam radiation

Charged particle radiation: Proton, helium ion

Plaque brachytherapy

|

|

Tumors

|

Choroidal melanoma

Iris melanoma

Ciliary body melanoma

Retinoblastoma

Hyperviscosity syndromes

Myeloproliferative disorders

|

|

Inflammatory Diseases

|

Chronic uveitis

Chronic iridocyclitis

Behcet disease

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome

Sympathetic ophthalmia

Endophthalmitis

Panophthalmitis

Crohn disease

Giant cell arteritis

Trauma

|

|

Surgical Causes

|

Carotid endarterectomy

Pars plana vitrectomy

Cataract extraction

Nd:YAG Capsulotomy

Laser pupiloplasty

|

|

Extravascular Disorders

|

Ocular ischemic syndrome

Carotid artery obstructive disease

Carotid-cavernous fistula

|

Etiologies of Neovascular Glaucoma

- Among the various causes of NVG, 3 diseases constitute most of the NVG cases encountered in the clinic. These diseases are diabetic retinopathy (33%), ischemic central retinal vein occlusion (33%), and ocular ischemic syndrome (13%).[5][2]

- Up to 60% of the eyes with ischemic CRVO develop neovascularization of the anterior segment of the eye within a few weeks to 2 years after the onset of CRVO.[7] Eyes with non-ischemic CRVO have a risk of conversion to ischemic CRVO, which has been reported to occur at a rate of 3.3% by 4 months and an incidence rate 10 times higher by 3 years.[8]

- Neovascularisation of the iris occurs in 1% to 17% of eyes with diabetic retinopathy. This rate is particularly higher for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.[9][10]

- Ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS) is commonly unilateral, with 20% of cases being bilateral. Global ischemia causes both anterior segment and posterior segment neovascularization in OIS. Severe carotid artery occlusion and diabetic retinopathy are usually associated with OIS.[11]

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of NVG vary in different populations and according to various etiological diseases causing NVG. In a tertiary eye hospital in China, the number of NVG cases was found to be 483 (5.8 %) out of the 8306 glaucoma patients seen over 11 years.[12] The prevalence of NVG among migrant Indians in Singapore was 0.12%.[13] The prevalence of NVG was 0.01% in the population-based Hooghly River Study in West Bengal, India.[14]

The reported proportion of NVG among patients with secondary glaucoma has ranged from 9 to 17.4% in hospital-based studies. Among the eyes with ischemic CRVO, 40 to 45% develop NVG.[15][16] Eyes with ischemic CRVO are more prone to NVG, with an estimated 3,800 patients developing NVG each year.[7]

In eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, 65% of the eyes develop NVI. In eyes with PDR and NVG in 1 eye, the risk of development of NVG in the other eye is 33%.[17] In OIS, 68% of eyes can develop NVG, with an increased risk associated with more advanced carotid stenosis.[18] In the Diabetes Control Complications Trial (DCCT), 24% of NVG over 9 years was found amongst the patients in the standard treatment group compared to 8% in the intensive treatment group.[19]

Pathophysiology

The inciting event for neovascular glaucoma is retinal ischemia.[4] All the diseases underlying NVG result in retinal ischemia due to the disease process. Retinal ischemia causes an imbalance between the pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors. The major pro-angiogenic factors include vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hepatocyte growth factor, tumor necrosis factor, insulin-like growth factor, and inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6. The major anti-angiogenic factors include pigment epithelium-derived factors, transforming growth factor-beta, somatostatin, and thrombospondin.[20][21][22][23]

VEGF can cause mitosis and migration of vascular endothelial cells and leukocyte adhesion at the endothelial cells. These events can lead to a breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier.[24] Retinal ischemia and consequent events result in the formation of new leaky vessels over the iris and angle of the anterior chamber. It has also been postulated that oxygen from the aqueous humor diffuses posteriorly in the eyes with hypoxic retina. This, in turn, causes the release of VEGF from the non-pigmented epithelium of the ciliary body, which causes new blood vessel formation in the anterior segment of the eye.[25] This stage is known as the stage of rubeosis iridis. Factors like transforming growth factor-beta (1 and 2) and fibroblast growth factor contribute to the development of fibrovascular membranes over the surface of the iris and the angle of the anterior chamber.[26]

This fibrovascular membrane has proliferated myofibroblasts. This membrane can cover the surface of the iris and the angle of the anterior chamber, obstructing the flow of aqueous humor through the trabecular meshwork. This is known as the secondary open-angle stage of NVG. Over some time, this fibrovascular membrane contracts to cause secondary angle-closure glaucoma. This is known as the secondary closed-angle stage of NVG. Both the secondary open-angle and angle-closure stages are associated with raised IOP.

Ischemia of the retina and optic nerve head results in deleterious effects on the vision of the eyes with NVG. Ocular perfusion pressure is the difference between arterial Blood pressure (BP) and intraocular pressure (IOP).[27] Arterial BP is diastolic BP + 1/3 (systolic BP – diastolic BP). A low arterial BP can further aggravate the ischemia of the retina and the optic nerve head; thus, a low systemic arterial blood pressure should be avoided in patients with NVG.[15]

Histopathology

Histologically, new blood vessels are seen over the surface of the iris and rarely on the iris stroma. These blood vessels are formed due to the budding of endothelial cells from the capillaries. These vessels arise from the vessels over the iris' root or the major arterial circle. These vessels are devoid of a muscular layer and have little adventitial tissue. The fibrovascular membrane comprises myofibroblast and proliferating smooth muscle tissue and can extend over the surface of the iris and the angle of the anterior chamber.[28][29]

History and Physical

The etiology of NVG is multifactorial, and the clinical history should cover the detailed aspects of the particular etiology. Patients with diabetes mellitus should be evaluated thoroughly regarding their glycemic control and other associated comorbidities like hypertension, hyperlipidemia, anemia, nephropathy, and cardiopathy.

Patients with CRVO should be evaluated for various etiologies of thrombotic events. The systemic etiologies include diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hyperviscosity syndromes, myeloproliferative disorders, protein C and protein S deficiency, Factor V Leiden mutation, smoking, oral contraceptive pills, and pregnancy. An important associated ocular factor is glaucoma. Patients with OIS may have a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke. Detailed neurological evaluation is necessary for these patients.

Patients with prior ocular surgeries, such as pars plana vitrectomy, glaucoma filtration surgeries, and cataract surgeries, should be evaluated for previous intra-operative complications, if any. Intra-operative posterior capsule tear and vitreous loss are associated with a higher rate of NVG in the eyes of patients with PDR. Similarly, eyes with aphakia are at higher risk of NVG than pseudophakia. Recurrent retinal detachments in the eyes and having undergone vitreoretinal surgeries are risk factors for NVG.

Patients coming from geographic locations or ethnicities with significant rates of sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies need to be evaluated regarding the possibility of sickle cell anemia, prior blood transfusions, and pain in the extremities.

Pediatric age group patients should be evaluated for low birth weight, premature birth, neonatal septicemia, twin babies, and neonatal oxygen administration. All these predispose to retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and can cause NVG. Children should be evaluated for retinoblastoma, and a family history of retinoblastoma needs to be taken. Examination for pediatric conditions such as persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV) or Coat disease should be performed.

Patients with a prior history of uveitis need to be evaluated regarding the frequency and chronicity of red and painful eyes. Any history of ocular tumors such as choroidal melanoma, retinoblastoma, iris melanoma, and ciliary body melanoma should be elicited. Similarly, a history of ocular or periocular radiation therapy for tumors should be elicited.

Symptoms

An eye with NVG is typically chronic, painful, and red. Sometimes, the intensity of pain and redness may be less pronounced, particularly in young patients with good endothelial reserve. Light sensitivity and blurry vision may be the initial symptoms in some patients.

Signs

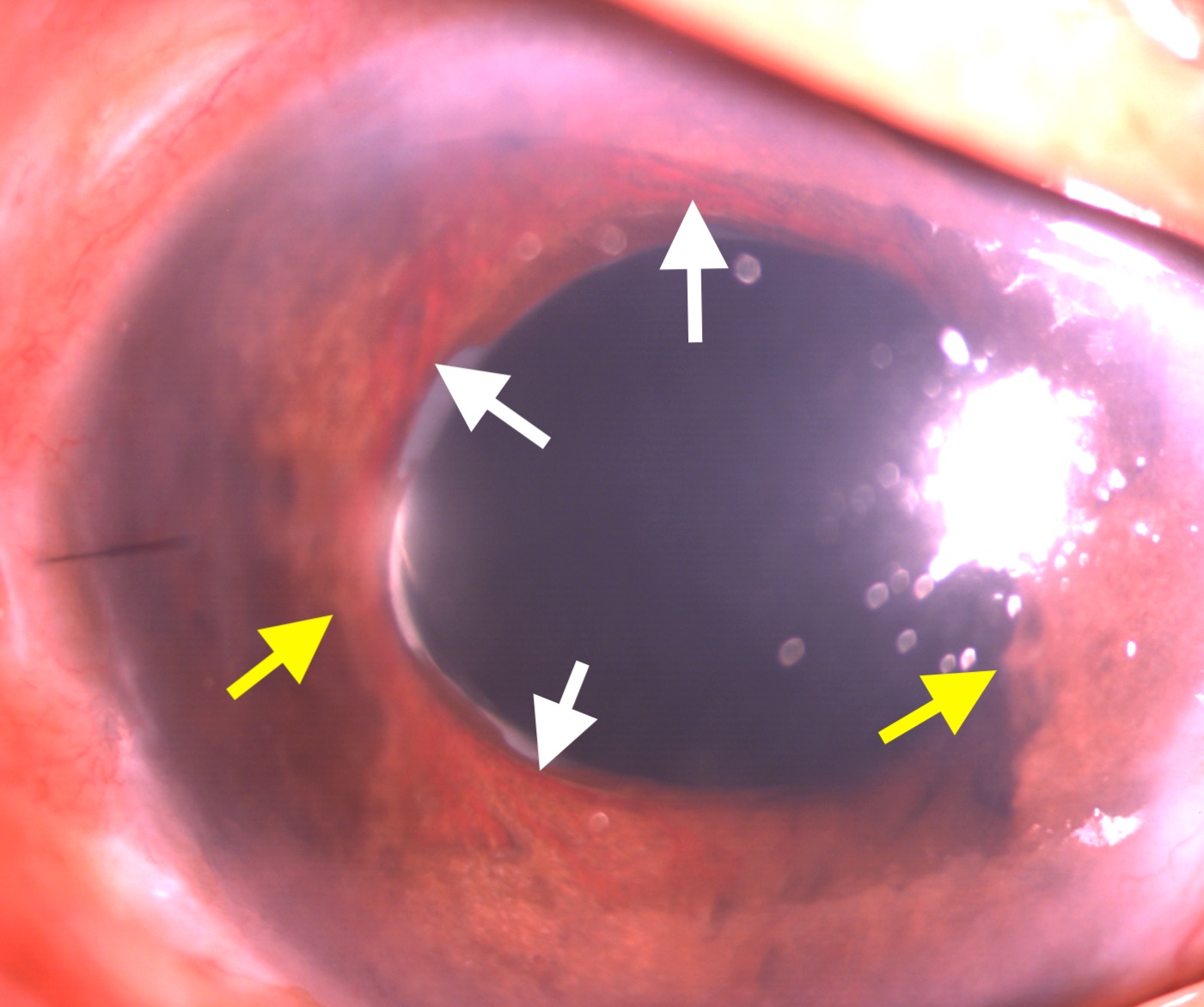

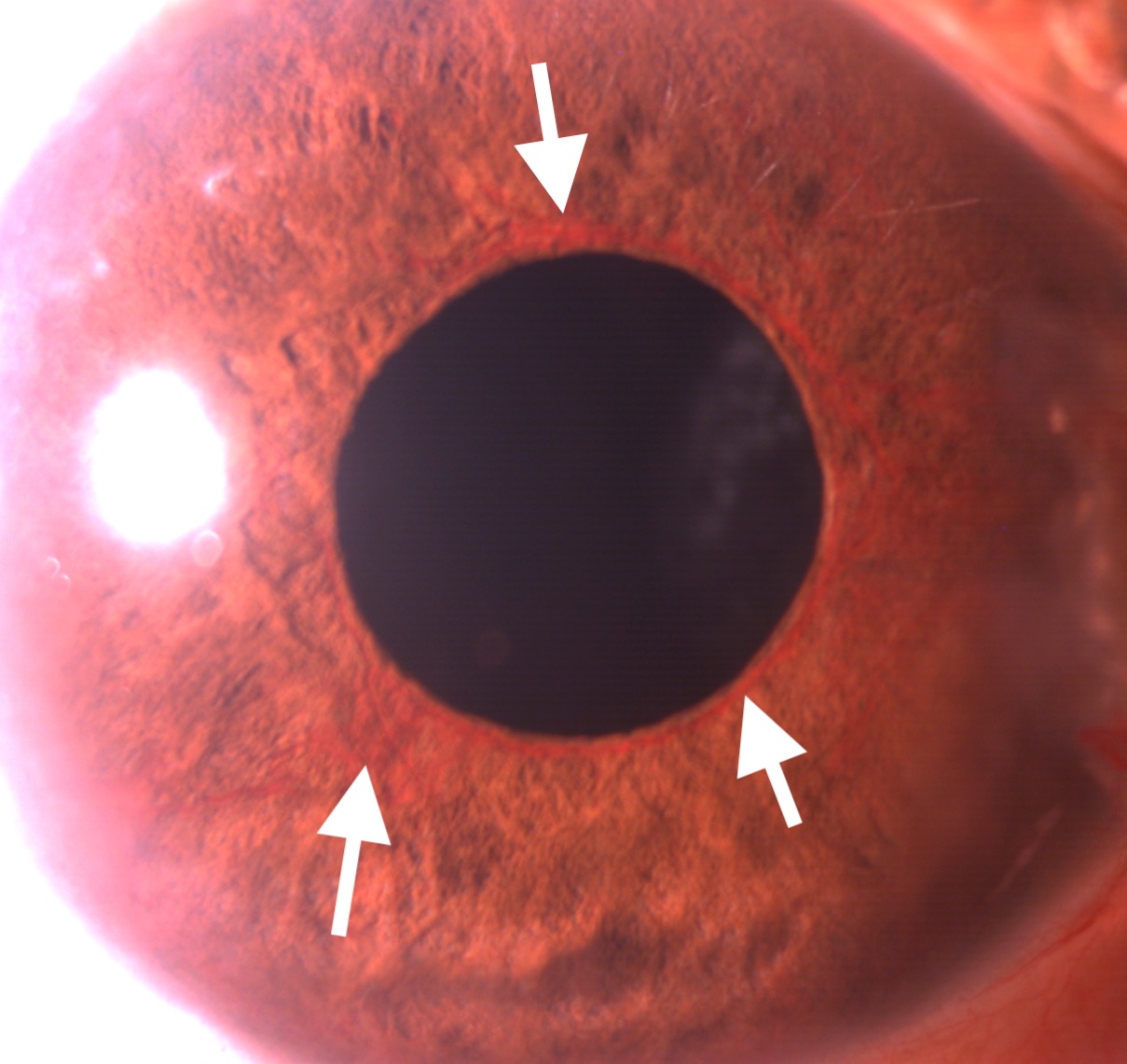

The intraocular pressure in the eyes with NVG is high, often over 50 mm Hg. Corneal edema may or may not be present. The hallmark signs of NVG on anterior segment examination are neovascularization of the iris (NVI) and neovascularization of the angle (NVA). The earliest detection of NVI can be done by the leakage of dye noticed after intravenous injection of fluorescein dye. The NVI appears as fine; new blood vessels are typically present at the border of the pupillary margin (see Image. Slit-lamp Examination Showing Neovascularization of Iris). Sometimes, these vessels can be found at the margin of the iridotomy. These vessels can be differentiated from the normal vessels originating from the ciliary body present over the iris. The latter originates from the root of the iris, travels towards the pupillary border, and disappears in the iris stroma midway. NVA is a finding of gonioscopy. NVA appears as thin vessels over the trabecular meshwork crossing the scleral spur. Though isolated NVA without NVI is rare, sometimes NVA can be found before developing clinically detectable NVI.[30]

NVG can be divided into 4 stages. First is the pre-rubeotic stage, where the new vessels over the iris are not clinically detectable but can be found on fluorescein angiography by the leakage of dye from the margin of the pupillary border. The second is the rubeotic stage, where the new blood vessels can be detected in the form of NVI or NVA. The third is the open-angle stage, where the fibrovascular membrane covering the anterior chamber and iris angle obstructs the aqueous outflow. Fourth is the closed-angle stage due to the contraction of the fibrovascular membrane over the angle of the anterior chamber.[2]

Evaluation

Investigations into the diagnosis of NVG can be broadly categorized as ophthalmic and systemic investigations.

Ophthalmic Investigations

Slit-lamp biomicroscopy: Slit-lamp biomicroscopy is indispensable for detecting NVI and NVA during the workup of a patient with NVG. The fine new vessels can be found over the iris surface, mainly near the pupillary margin. Sometimes, peripheral anterior synechia can be found in the eyes with NVI (see image. Neovascularization of Iris and Peripheral Anterior Synechia). Red blood cells can sometimes be seen in the anterior chamber.

Gonioscopy: This is a dynamic investigation, preferably done in an undilated pupil. New blood vessels can be found at the angle of the anterior chamber, over the trabecular meshwork, and crossing the scleral spur.

Fundus Fluorescein Angiography (FFA) of the retina and iris: Fundus fluorescein angiography is an invasive test to detect the neovascularization of the optic disc (NVD) neovascularization elsewhere (NVE) and areas of capillary nonperfusion (CNP). The former 2 are hyperfluorescent lesions, and the latter is a hyperfluorescent area. Recent advancements in ultra-wide-field FFA can capture the retinal image up to a 200-degree area of the retina, thus identifying peripheral lesions like NVE and CNP areas better than conventional FFA.[31]

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) of the retina: OCTA is a rapid, non-invasive modality for diagnosing NVD, NVE, and CNP areas. Wide-field OCTA can capture 12 × 12-mm fovea-centered images.[32] OCTA can also be used to monitor disease status over subsequent visits.

OCTA of iris: Neovascularization of the iris can also be detected using OCTA.[33]

B-scan ultrasound for posterior segment examination: Ultrasonography B scan is helpful in the detection of lesions of the posterior segment of the eyes in certain conditions. B scan can detect the presence of vitreous hemorrhage, additional fibrous proliferation, and tractional or rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Mass lesions like choroidal melanoma, ciliary body melanoma, and retinoblastoma can be detected. B scan can detect retinal detachment in the advanced stages of ROP with NVG.

Systemic Investigations

Various systemic diseases can be associated with a case of NVG, depending on the specific etiology causing NVG. The investigations for various systemic diseases are as follows:

- Hypertension (associated with retinal venous and arterial occlusion): Blood pressure

- Diabetes (can cause retinal veinous and arterial occlusion, PDR): Blood sugar levels, HbA1c

- Hyperlipidemia (can cause retinal veinous and arterial occlusion): Lipid profile

- OIS: carotid doppler, magnetic resonance angiography

- Uveitis: HLA B-27 assay, treponema serology, Tuberculosis testing (QuantiFERON-TB Gold, Mantoux), Sarcoidosis (ACE, chest X-ray)

- Blood dyscrasia: Complete blood counts, ESR, CRP, Plasma electrophoresis, and specific testing for hyperviscosity syndromes.

Treatment / Management

The principles of management of NVG are as follows:

- Identifying and managing the etiological factors (diabetes, carotid artery obstruction, or other causes as enumerated in Table 1) causing retinal ischemia.

- Retinal ischemia is treated by pan-retinal photocoagulation or intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents.

- Control of intraocular pressure medically and surgically.

- Control of inflammation using topical corticosteroid drops.

- Mydriatics such as topical atropine drops

Identifying and managing the etiological factors (as described under the section of etiology) and investigations related to those factors (as described under the section of systemic investigations) are crucial in curtailing the ongoing mechanism of retinal ischemia. This also prevents the contralateral eye from developing NVG in patients with unilateral NVG at presentation. Patients with uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and nephropathy should be managed with the help of a physician.

Patients with severe carotid artery obstruction may need carotid endarterectomy, as per the discretion of the vascular surgeon. Blood dyscrasias and hematological abnormalities must be managed as per the internist and hematologist. Patients with uveitis need corticosteroid treatments, cycloplegics, and management of the specific etiology of uveitis. Intra-ocular tumors such as choroidal melanoma or retinoblastoma require treatments specific to the tumor characteristics and available treatments.

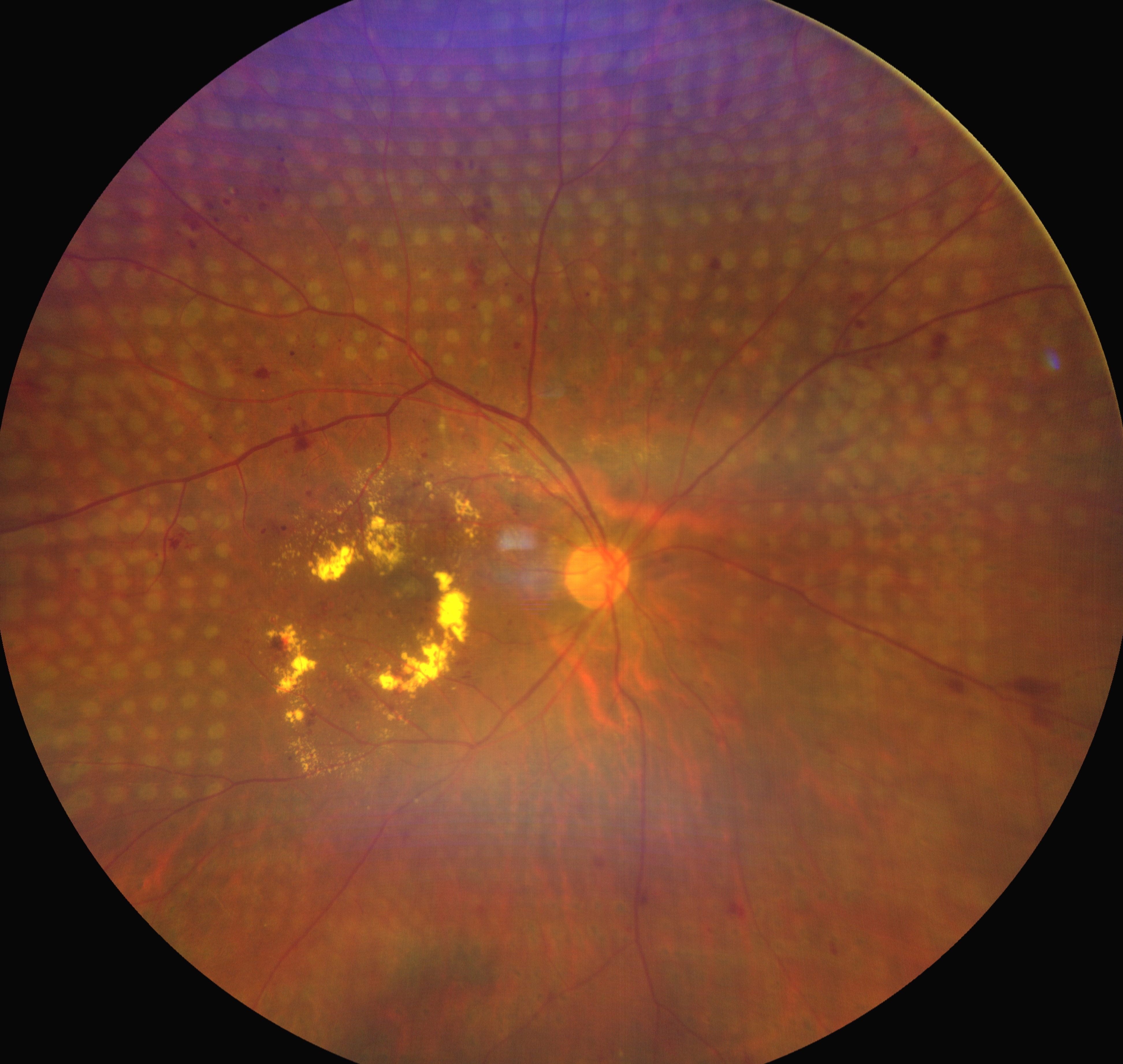

The treatment of retinal ischemia is comprised of pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) and intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. PRP does not immediately reduce neovascularization but has a longer treatment effect when compared to anti-VEGF injections. As a result, a combination of these treatments is often given initially. Typical settings of PRP include spot size of 400 to 500 microns, laser burns spaced 1 burn-width apart, grade 3 laser burns, and 1200 to 1600 burns per sitting if planned in 2 sittings. Usually, the PRP is completed in 2 or 3 sittings, separated 5 days apart (see Image. Regressed Neovascularization of the Disc and Neovascularization Elsewhere in an Eye With Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy). However, the presence of media haze, including cornea edema due to raised IOP, cataract, and vitreous hemorrhage, precludes the delivery of PRP.

Corneal edema may necessitate intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents and topical and systemic antiglaucoma medications to reduce the IOP and improve the corneal clarity, after which PRP can be performed. In cataracts obscuring the view to the fundus, intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents is required to reduce the NVI and NVA. Additionally, topical and systemic antiglaucoma medications need to be used to reduce the IOP. Cataract surgery can be performed after the regression of anterior segment neovascularization starts and there is a decrease in IOP. In the presence of vitreous hemorrhage, intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents and topical and systemic antiglaucoma medications should be started immediately, and pars plana vitrectomy should be considered as soon as feasible. Intravitreal injections are useful in decreasing the VEGF drive in the retina of the eyes with NVG and are very important in managing retinal ischemia.

Intraocular pressure management often requires topical and systemic medications initially, and ultimately, surgical management is often necessary. Topical beta-blockers, alpha agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are frequently used to manage IOP in eyes with NVG. Prostaglandin analogs can increase inflammation but are still often used as maximum medical treatment may be necessary. Systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are also useful in the short-term management of IOP but must be used cautiously in patients with renal impairment. Surgical management of IOP is indicated where the maximal medical management fails to control the IOP. Surgical management of high IOP in the eyes with NVG includes trabeculectomy or glaucoma drainage device. Though trabeculectomy is less preferred in eyes with NVG due to their high failure rate, there are some studies describing improved success rates of trabeculectomy augmented by anti-metabolites such as mitomycin C (MMC) or 5-Fluorouracil.[34]

In 1 study, the success rate after trabeculectomy with MMC was reported to be 62% at the end of 1 year post-operatively; however, this decreased to 51.7% at the end of 5 years. Preoperative intravitreal anti-VEGF agents have been shown to reduce the failure rate of trabeculectomy in the eyes with NVG.[35]

While there is no consensus regarding the surgical approach to NVG, recent studies suggest early implantation of GDD for the successful management of NVG.[36] In 1 study by Noor N A et al, GDD combined with intravitreal bevacizumab could maintain better visual acuity than GDD alone at 3 years post-surgery. However, there was no significant difference in the final surgical success rate.[37] Transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (TSCPC) is a surgical treatment option, particularly for eyes with poor visual potential and IOP elevation refractory to medical treatments.

Eyes with NVG often have associated inflammation, especially in the acute phase, which can be treated with topical corticosteroid eye drops. Prednisolone acetate 1% can be used in tapered doses. The pain and discomfort due to cyclospasm in the eyes with NVG can be mitigated with the help of cycloplegic eye drops such as atropine or cyclopentolate. Eyes with NVG, no perception of light (PL), and no pain do not need treatment and can be observed. However, if these eyes are painful, they must be treated with pressure-lowering drops, cycloplegics, and possibly TSCPC.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of NVG includes diseases with similar clinical presentations and diseases that can be ascribed to the etiologies of retinal ischemia.[15][4]

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma is a close mimicker of NVG where corneal edema, anterior segment inflammation, and minimally engorged iris vessels can be associated with raised IOP. A gonioscopy of the other eye assists in diagnosing the findings of a shallow anterior chamber and occlude angle. Fundus examination may be difficult in the presence of a hazy cornea. Retinal ischemia should be ruled by fundoscopy or, if needed, by fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA).

- Eyes with acute or chronic uveitis may mimic NVG. The presence of keratin precipitates (KPs) lining the endothelium and engorged blood vessels (rather than fine, lacy vessels) over the iris can suggest uveitis as the underlying etiology.

- Eyes in the post-operative period of anterior segment ophthalmic surgeries may present with engorged iris vessels. However, these vessels can be differentiated from neovascularization of the iris. These engorged blood vessels are radial, present over the iris stroma, and do not cross the scleral spur, unlike the arborizing superficial placed NVI, which crosses the scleral spur.

- Eyes with posterior segment tumors may present with engorged iris vessels. These tumors should be diagnosed promptly using fundoscopy, B-scan ultrasound, UBM, gonioscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

- A carotid-cavernous fistula can present with new blood vessels over the iris. Gonioscopy in these eyes can find blood in the Schlemm’s canal. Radiology of the brain and orbits aid in the diagnosis.

- The ocular ischemic syndrome presents with anterior segment neovascularization, possibly associated with normal or low IOP. Carotid doppler study or magnetic resonance angiography helps identify the carotid vessels' stenosis.

- Neovascularization of the anterior segment of the eye can also be seen in anterior segment dysgenesis (especially essential iris atrophy). Corectopia and iris atrophy can help diagnose these eyes. Other conditions, such as pseudoexfoliation syndrome and Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis, can also present with new vessels over the anterior segment of the eyes and raised IOP.

Prognosis

The prognosis of NVG is guarded. The prognosis depends upon prompt prophylaxis or treatment of retinal ischemia. Another important factor for the visual prognosis is the control of IOP. IOP elevation is often recalcitrant to medical treatment. The success rate of trabeculectomy in NVG is limited due to inflammation and hyphema. However, in the eyes that have received prior intravitreal bevacizumab injections, prior pan-retinal photocoagulation of the retina, and concurrent application of mitomycin-C or 5-fluorouracil, the success rate has been reported to be higher. Though the success in the control of IOP in trabeculectomy with MMC is described to be between 62% to 82% at the end of 1 year, the success rate decreases drastically over the following years. Eyes operated on with GDD have been reported to have more successful IOP control.[38][39][37]

The valved and non-valved GDDs have been reported to control the IOP in eyes with NVG effectively.[40] Intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents and GDD may have better results in maintaining vision and controlling IOP than GDD alone.[37][39] Early surgery with GDD may be preferred over an initial trabeculectomy in these eyes with NVG. Gnanavelu S et al did not find any difference in the failure rate of the eyes with NVG treated with a GDD among various causes of NVG, such as CRVO, PDR, and other etiologies.[36]

Complications

NVG complications can be categorized as complications of the disease process and complications of the treatment modalities. The complications of the disease process include corneal decompensation due to prolonged elevation of IOP, ectropion uvea due to contracture of the fibrovascular membrane over the surface of the iris, and angle of the anterior chamber, and loss of vision from retinal ischemia or glaucomatous optic neuropathy.

The most common complication of the surgical management of control of IOP is hyphema, which ranges from 4 to 85%.[41][42] Other complications include serous choroidal detachment in up to 20% of eyes and suprachoroidal hemorrhage in up to 5% of eyes.[42]

Though rare, complications such as phlebitis, bleb leak, and endophthalmitis can be expected in eyes undergoing trabeculectomy, irrespective of the indication of the surgery. Complications specific to GDD include erosion of the conjunctiva overlying the GDDs (up to 12.5% of eyes), tube block, and corneal endothelial defects due to touch with the tip of the tube (up to 3 to 14% of the eyes).[43][44] TSCPC complications include phthisis and scleral thinning. All surgical treatments, particularly TSCPC, carry a risk of sympathetic ophthalmia.

Deterrence and Patient Education

NVG is often refractory to treatment and has a poor prognosis in terms of IOP control and maintenance of vision. A delay in presenting to the ophthalmic clinic is associated with worse outcomes for the patient. Patients with NVG need to seek prompt treatment from the ophthalmic caregiver.

Vulnerable patients with risk factors like DM, HTN, hyperlipidemia, carotid vascular diseases, and ocular tumors should be counseled regarding the symptoms of NVG. The ophthalmologists giving primary care to patients with NVG must not hesitate to refer them to a referral center for treatment, such as GDD surgeries and intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. The patients must follow the strict follow-up protocol, as multiple visits are often required. The patients must be counseled about the guarded prognosis related to the control of IOP and visual gain.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Several systemic diseases can result in NVG. Diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and blood dyscrasias require management by an internist. However, the ophthalmologist may alert the internist and patient regarding the need for improved control of their systemic disease. The presence of carotid artery obstruction in ocular ischemic syndrome requires prompt evaluation by an interventional cardiologist or endovascular surgeon.

The presence of systemic or ocular malignancies may require treatment coordinated through an oncologist. The assistance of a caregiver or patient advocate is often helpful in ensuring treatment compliance and follow-up of the ocular and systemic conditions associated with NVG. Thus, coordination between different subspecialties should be emphasized rather than isolated ophthalmic care for optimal outcomes of NVG.