Continuing Education Activity

Bacterial keratitis or corneal ulcer is a common sight-threatening ocular corneal pathology. In some cases, there is rapidly progressive stromal inflammation. If untreated can lead to progressive tissue destruction, corneal perforation, or extension of infection to adjacent tissue. Bacterial keratitis is commonly associated with risk factors that disturb the corneal epithelial integrity. A meticulous slit lamp clinical examination, corneal scraping with smearing, and culture are mandated to reach a conclusive diagnosis. Antibacterials are the mainstay of treatment and adjuvant in the form of cycloplegics, antiglaucoma medications, and oral anti-inflammatory drugs. Rapidly progressive cases unresponsive to medical treatment require therapeutic keratoplasty. This activity aims to give deeper insight into etiology, risk factors, epidemiology, clinical presentation, microbiological and histopathological analysis, treatment, complication, differential diagnosis, and prognosis of bacterial keratitis.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiology of bacterial keratitis.

- Review the pathophysiology of bacterial keratitis.

- Summarize the management and differential diagnosis of bacterial keratitis.

- Explain the evaluation of bacterial keratitis.

Introduction

Bacterial keratitis or corneal ulcer is an infection of the corneal tissue caused by varied bacterial species. It can be an acute, chronic, or transient infectious process of the cornea with a variable predilection for topographical, anatomical, or geographical domains of the cornea.[1] It can present as insidious progressive ulceration or rapidly deteriorating suppurative infection of any part of corneal tissue. The cornea can be invaded by various microorganisms like viruses, fungi, protozoa, and bacteria, but bacteria are most concerning due to rapidly progressive vision-threatening keratitis with irreversible visual sequelae.[2]

When anatomical, mechanical and antimicrobial barriers of microbial keratitis are breached, it invites vision-threatening keratitis. The past few decades have seen a rapid increase in contact lens users globally, resulting in an increase in bacterial keratitis proportionately.[3][4]

The diagnosis rests on clinical and microbiological evaluation. With rapid advances in clinical diagnosis, growing research in molecular laboratory investigation, and targeted antimicrobial therapy, the visual morbidity has reduced to a decent extent, but it remains a significant cause of sight-threatening keratitis in underdeveloped and rural areas globally.[5]

Etiology

The main barriers of microbial infection are anatomical barriers in the form of the bony orbital rim, eyelids, intact conjunctival and corneal epithelium, mechanical barriers like tear film mucus layer and lacrimal system, and antimicrobial barriers like tear film constituents IgA, complement components, lactoferrin, lysozymes and conjunctiva associated lymphoid tissue (CALT). When these barriers are disrupted, it may result in bacterial keratitis.[6]

Contact lens use is one of the major causes of bacterial keratitis. The various factors which cause bacterial keratitis are contact lens (CL) overnight wear, overwear, inadequate cleaning of contact lens, rinsing the contact lens in tap water, contamination, lack of CL hygiene, bandage contact lenses, CL sharing, swimming with contact lenses, CL solution contamination, and CL induced trauma.[7] The various extrinsic causes implicated are trauma, foreign body injury, chemical, mechanical and thermal injuries, insect fall, previous ocular and eyelid surgery, immunosuppression, drug-induced with corticosteroids and NSAID’s and substance abuse.[8]

Varied ocular surface diseases, either local or systemic, can also result in bacterial keratitis. The various local factors are dry eyes, corneal suture-related infection, abnormalities of eyelid anatomy and function, trichiasis, blepharitis, chronic dacryocystitis, ectropion, entropion conjunctivitis, lagophthalmos neurotrophic keratopathy, recurrent corneal erosions, epithelial defect, secondary bacterial keratitis after viral keratitis, bullous keratopathy.[9] The systemic conditions predisposing to bacterial keratitis are diabetes mellitus, malnourishment, connective tissue or autoimmune pathologies, Steven-Johnson syndrome (SJS), ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid (OMMP), atopic dermatitis, xerophthalmia, blepharoconjunctivitis, 5th and 7th cranial nerve palsy, graft versus host disease, immunosuppression (AIDS) and chronic alcoholism.[10]

The bacterial species causing keratitis are the following:

- Gram-positive cocci include Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Gram-positive bacilli include Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Corynebacterium xerosis

- Gram- negative bacilli includes Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter species

- Enterobacteriaceae species include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Serratia, and Proteus mirabilis

- Gram-negative diplococci, namely Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis

- Gram-negative diplobacillus include Moraxella lacunata

- Non-tuberculous mycobacterium includes Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae.

- Gram-negative coccobacillus include Haemophilus influenza and Haemophilus aegyptius

- Gram-positive filamentous bacteria include Nocardia asteroids and Nocardia brasiliensis

- Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus is one of the most common bacterial species identified recently

The most common species causing bacterial keratitis include Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeuruginosa, and species of the Enterobacteriaceae family.

The bacterial species that can penetrate the intact corneal epithelium are Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Hemophilus aegyptius, and Listeria monocytogenes.[11]

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of bacterial keratitis vary with the geographical location and local environmental and climatic risk factors.[12] There is a vast disparity among populations in the incidence of bacterial keratitis in developed countries like the USA and Europe compared to developing countries like India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.[5] This variation is because less industrialized nations have a significantly lower frequency of contact lens users. As a result, contact lens-related bacterial keratitis is also less.[13]

In the USA, the reported incidence is 11/1 lakh users compared to Nepal with 799/1 lakh users. The annual incidence of microbial keratitis in the USA is 71,000 cases.[14][15] The normal human eye rarely develops bacterial keratitis because the normal human cornea is resistant to infection. In a study by Ormerod et al. in North America, they described staphylococcal, Pseudomonas, and Streptococcus as the major causes of microbial keratitis.[16] Neuman and Sjostrand, in their analysis, reported Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis as the most common gram-positive bacteria and Pseudomonas as the most common gram-negative bacteria.[17]

The incidence of corneal ulcers has progressed from nearly zero in early 60 to 52% in the 1990s. Erie et al. also reported that the incidence of ulcerative keratitis rapidly progressed from 5.3 to 435% from 1950 to 1980. He concluded contact lens to be a significant contributor. The reported annual incidence of ulcerative keratitis in contact lens users is 4 to 21 per 10,000 extended wear and daily wear for soft contact lens wearers. The overall most common reported causes of bacterial keratitis are Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas.[18] In studies from Italy and UK contact lens was found to be a more common predisposing risk factor for bacterial keratitis. Data from two hospital sets from Los Angeles reported gram-positive pathogen.[19]

A two hospitals analysis from Los Angeles, USA, reported coagulase-negative staphylococcus as the most common gram-positive pathogens and Pseudomonas aeruginosa as the most common gram-negative bacteria.[20] Another analysis from the USA reported more prevalence of gram-negative organisms from the southern USA than the northern part of the country.[21] A study from Texas reported gram-negative bacteria as the most common isolate.[9]

Polymicrobial keratitis can also occur while analyzing culture. A study reported 43% of cultures having two or more bacterial microorganisms. Staph. epidermidis and Fusarium have been reported as the most common etiology for polymicrobial keratitis, with trauma being the most common risk factor.[22] The Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT) from South India reported 51.5% cases of Streptococcus pneumoniae, 22.75 cases of Pseudomonas, and 11.5% cases of Nocardia.[23]

Pathophysiology

The process of bacterial keratitis initiates once the epithelial is breached by any means. The epithelial defect invites invasion by various bacteria.[1]

Pathophysiology of Focal Bacterial Keratitis

The development of bacterial keratitis progresses through four stages

- Stage of progressive infiltration-

- Stage of active ulceration

- Stage of regression

- Stage of cicatrization[24]

The final course of bacterial keratitis is dependent on the virulence of the offending bacteria, host defensive mechanisms, and the treatment received

Pathophysiology of Perforated Bacterial Corneal Ulcer

Perforation of bacterial corneal ulcers results from rapid keratolysis and a stromal melt, and the ulcerative process reaches up to the Descemet membrane (DM). The DM has high resistance, and when it bulges out, it results in the formation of Descemetocele. Any maneuver at this stage raising the intraocular pressure like sneezing, coughing, straining may perforate the ulcer. After perforation, there is an immediate gush of aqueous humor which reduces the intraocular pressure, the iris lens complex moves forward, and the patient is relieved of pain. The result of perforation depends upon the size and position of the defect. In cases with small perforation and opposite to iris tissue, it results in iris plugging and rapid healing. Hence, this results in the formation of adherent leucoma.[25]

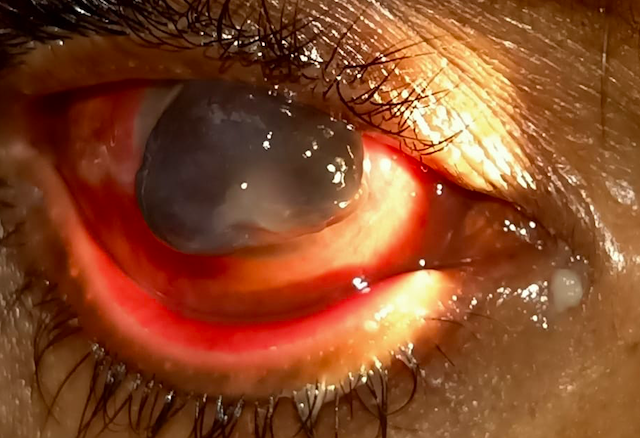

Pathophysiology of Sloughed Out Corneal Ulcer and Anterior Staphyloma Formation

When there is corneal invasion by highly virulent bacteria, and the body’s immune response is low, it sloughs the whole cornea leaving a narrow rim behind along with total iris prolapse. This results in iritis and, at the same time, exudate block the pupil and iris, resulting in the formation of a false cornea. When these exudates organize and form a thin fibrous layer of the conjunctival and corneal epithelium, it results in the formation of pseudocornea. The formed pseudocornea is very thin and cannot withstand the raised intraocular, which results in bulging forward of the cornea and the plastered iris tissue. As a result, an ecstatic cicatrix forms called anterior staphyloma. It can be partial or total, depending on the extent of involvement.[26]

Histopathology

Once the epithelium is breached, the stage of progressive infiltration is characterized by polymorphonuclear and lymphocyte infiltration in the epithelium along with the migration of similar cells from the nearby stromal tissue. Later it results in necrosis of the involved tissue depending on the host defense mechanism and virulence of the bacteria. In the stage of an active ulceration, there occurs necrosis and sloughing of the epithelium, bowman’s membrane, and stroma. The walls of the ulcer become swollen due to the imbibition of fluid and leucocyte infiltration. There can also be vascular congestion due to hyperemia of vessels and accumulation of purulent exudates in the cornea. There can also be iritis due to toxin absorption and congestion of the iris and ciliary body.

Migration of exudates from the iris and ciliary body in the anterior chamber results in hypopyon formation. The stage of regression is dominated by humoral antibody production and cellular defense mechanism. There is the formation of a line of demarcation along the ulcer edge, where there is an excess of leucocytes which help to neutralize and phagocyte the bacteria and necrotic debris. The initial digestion of necrotic debris may result in enlargement of the ulcer, followed by superficial corneal vascularization that augments the cellular and humoral immune response. The stage of cicatrization is the stage of ulcer healing which is characterized by progressive epithelization.

The fibroblasts and endothelial cells help form fibrous tissue beneath the epithelium, which aids in healing. Later the stromal thickening occurs, resulting in forwarding push of the epithelium. If the scar is superficial and involves epithelial and subepithelial surfaces and superficial stromal lamellae, it is called nebular opacity. When the scarring is beyond one-third of stromal tissue, it is called macular and leucomatous based on the visibility of underlying ocular structures like iris and pupil.[27]

History and Physical

The patient usually presents to the outpatient department with a history of either foreign body fall, insect injury, or chemical injury. Patients may also present with a history of stroke. The stroke patients with lagophthalmos may also manifest as exposure to bacterial keratitis. It is also vital to document the onset and duration of symptoms. Contact lens history in the form of frequency of use, overnight wear, solution of CL used type of CL, using tap water for cleaning CL, bath in a swimming pool or a lake with CL on, and cosmetic colored CL use. The history of previous viral keratitis, medications used, medication allergy, ocular surgery, dry eyes, previous similar episodes of bacterial keratitis must be excluded. History of vitamin A deficiency, malnutrition, HIV, and immunocompromised status must be documented.[1]

Based on clinical features, bacterial keratitis can be broadly categorized as one of the following:

Non-hypopyon Purulent Bacterial Ulcer

Hypopyon Bacterial Ulcer

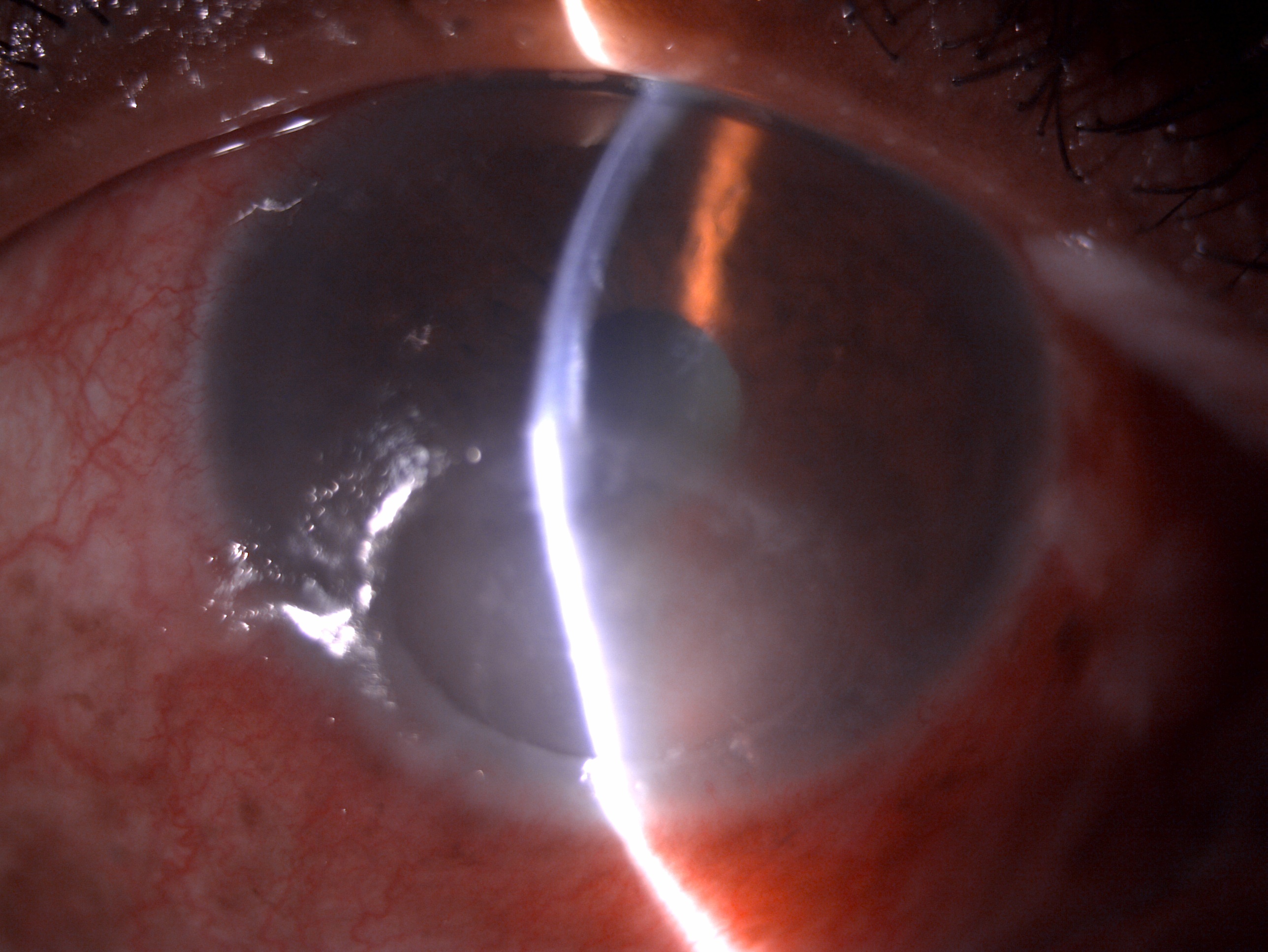

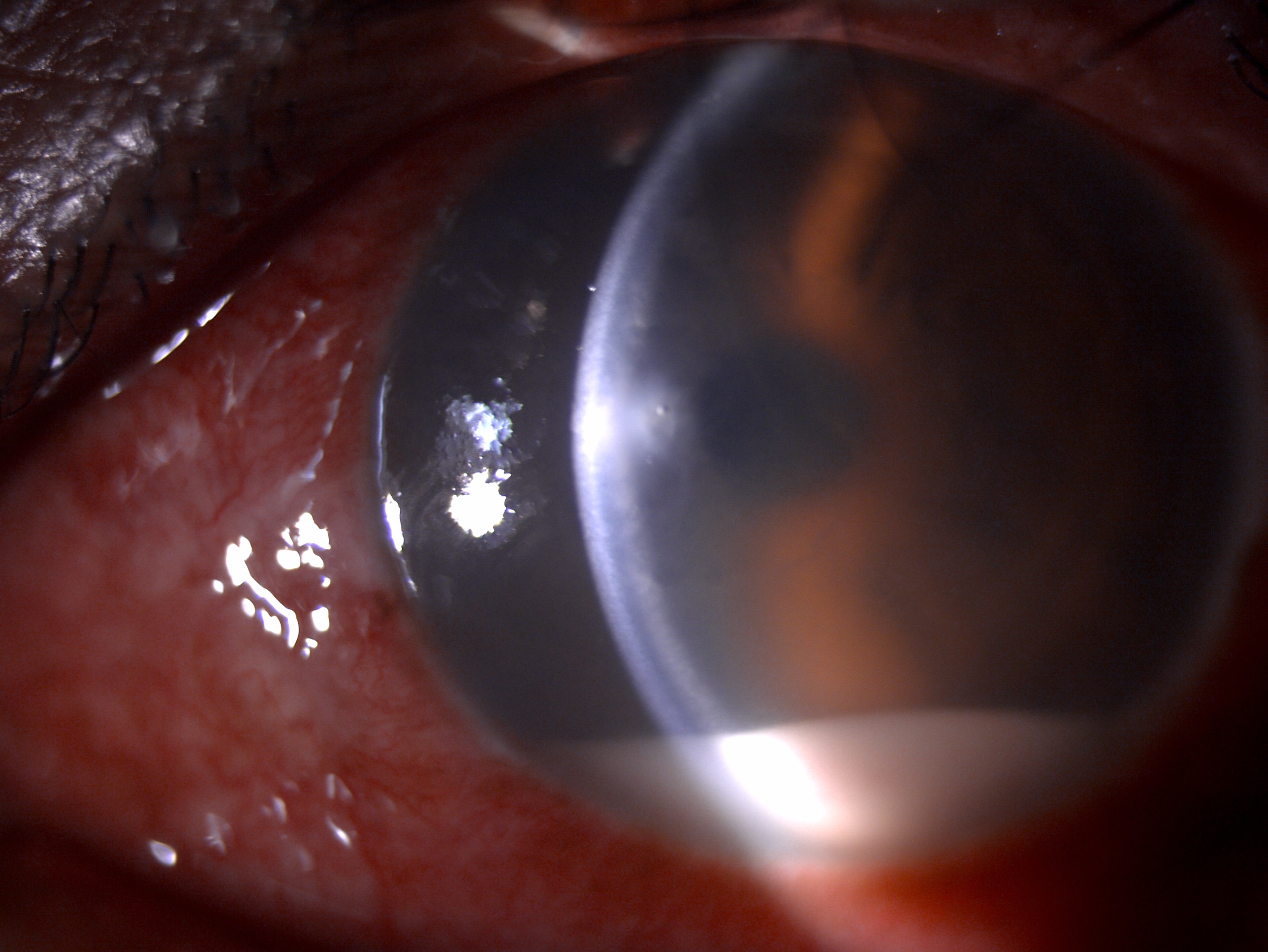

The common symptoms of bacterial ulcers are pain, redness, watering, mucopurulent or purulent discharge, photophobia, defective vision, foreign body sensation. Signs are more common than symptoms in bacterial keratitis. The various signs of bacterial keratitis are lid edema, blepharospasm, matting of eyelashes, purulent discharge, conjunctival chemosis, circumcorneal congestion, hyperemia, epithelial defect, stromal edema, stromal infiltrate, full-thickness infiltrate, Descemet membrane folds, endothelial plaque, hypopyon, and exudates in the anterior chamber, anterior uveitis, posterior synechiae, muddy iris, and small ischemic pupil. Scleritis can also result in a severe perilimbal infectious process. Rare cases with perforation or post-surgery can result in endophthalmitis.

Besides these findings, the examining ophthalmologist must actively look for the presence of any lid and adnexal pathologies in the form of meibomian gland disease, blepharitis, trichiasis, distichiasis, ectropion, entropion, lagophthalmos, and punctal abnormalities. The conjunctiva should be examined to rule out discharge, inflammation, follicles, papillae, cicatrization, symblepharon, scarring, keratinization, membrane, pseudomembrane, ulceration, evidence of prior surgery, ischemia, foreign body, or filtering bleb. The sclera should be examined for inflammation (infectious versus immune), ulceration, thinning, nodule and ischemia. The cornea should be examined in detail for any occult foreign bodies, suture-induced infiltrates, dystrophy, thinning, scarring, neovascularization, or flaps from previous corneal or refractive surgery. The contralateral eye should also be examined in detail.[28]

Hypopyon Bacterial Ulcer

Some of the pyogenic bacteria like staphylococci, streptococci, gonococci, Moraxella) may produce hypopyon. The most dangerous bacteria are Pseudomonas pyocyanea and Pneumococcus due to their high virulence. The characteristic hypopyon corneal ulcer caused by pneumococci is called ulcus serpens, and the most common source of infection is chronic dacryocystitis. The two main factors that promote the development of hypopyon bacterial ulcers are the bacteria's virulence and the host tissue's resistance. They are more common in old, debilitated, malnourished, and alcoholic patients. When the iritis is severe, it results in infiltration of leucocytes from the blood vessels. When these cells gravitate at the bottom of the anterior chamber, it leads to the formation of hypopyon. This hypopyon is sterile due to the outpouring of polymorphonuclear leucocytes rather than bacteria itself.[29]

Characteristic Features of Bacteria

Staphylococcal aureus

Seen in compromised corneas secondary to bullous keratopathy, chronic herpetic keratitis, dry eyes, and ocular rosacea. It usually presents with marked suppuration, oval, yellowish-white opaque deep stromal abscess. It is also capable of biofilm formation over the cornea and on contact lenses. Staphylococcus is also a major cause of keratitis after corneal cross-linking procedures.[30]

Staphylococcus epidermidis

It has an indolent course and may also result in a stromal abscess. The stromal infiltration is of comparatively lesser severity to that aureus.[31]

Streptococcus pneumoniae

It presents with a deep round to oval central stromal ulcer with a progressive edge, and the other edge is usually healing. It is an important cause of posterior corneal abscess and anterior chamber hypopyon.[32]

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

The bacteria have a characteristic greenish-yellow discharge with severe inflammation. The ulcerative process progresses rapidly with marked stromal melt, ring infiltrate, hypopyon, anterior chamber cells and flare, endothelial plaque, and later descemetocele formation or perforation. The keratitis has been described to produce a ground-glass appearance.[33]

Proteus

The clinical presentation is similar to Pseudomonas.

Klebsiella

It is rare keratitis often associated with chronic epithelial disease, and Klebsiella pneumoniae had also been reported in patients using contact lenses. Klebsiella oxytoca is another rare cause of bacterial keratitis after ocular surgery and topical corticosteroid use. The classical appearance of the ulcer has been described as greyish white pleomorphic suppuration with diffuse stromal opalescence.[34]

Moraxella

It is reported to produce keratitis after trauma in debilitated, immunocompromised, malnourished, pyridoxine deficiency, alcoholic, or diabetic patients. The bacteria causes severe indolent paracentral of peripheral oval stromal ulceration with the undermined necrotic edge, corneal perforation with mild to moderate anterior chamber reaction, hypopyon, and occasionally hyphema.[35]

Neisseria gonorrhea

It is characterized by chemosis, hyperpurulent conjunctivitis with rapidly progressive stromal infiltration.[36]

Nocardia

The bacteria can produce indolent ulcerations after minor trauma and exposure to contaminated soil. It is characterized by patchy anterior stromal, raised, superficial, small round pinhead-like mid-peripheral infiltrates in a wreath-like or necklace configuration with brush fire-like border and multifocal lesions. There may be epithelial or subepithelial lesions, anterior chamber reaction, and hypopyon. Rarely there may be peripheral superficial vascularization.[37]

Non-tuberculous Mycobacteria (M. chelonae, M. fortuim)

The bacteria manifest as slowly progressive multifocal or single lesion keratitis accompanied by multiple satellite lesions. The majority of cases have an intact corneal epithelium on presentation. The classical appearance has been described as a crack-windshield appearance due to radiating corneal infiltrate. Negligent cases result in hypopyon. The ulcer usually results from contaminated sharp instruments, after corneal trauma or surgery, particularly after LASIK. The ulcer heals very slowly. Rarely does it manifest as intrastromal opacities, infectious crystalline keratopathy, and mild to moderate inflammation.[38]

Bacillus Cereus

The keratitis occurs after trauma, wound contamination, or contact lens. It is usually characterized by a stromal ring infiltrate away from the site of trauma and results in rapid progression to a stromal abscess.[39]

Evaluation

Corneal Scraping

Scraping is usually indicated under the following scenarios:

- Large central corneal infiltrate with significant stromal involvement or melt.

- Chronic and unresponsive keratitis to broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Previous history of corneal surgery.

- Atypical clinical features

- Significant multiple infiltrates in different locations of the cornea.

Scraping is performed under topical anesthesia (preservative-free) with 0.5% proparacaine or proxymetacaine 0.5%. The preservative-free formulation is preferred as a preservative may lower the bacterial viability for culture. Tetracaine can also be employed as it has a greater bacteriostatic effect. They are taken with the help of a disposable number 11 or 15 Bard-Parker blade, or 26 G bent hypodermic needle or sterile kimura or platinum spatula. Before performing scraping, the loose mucus, dead and necrotic tissue is removed from the ulcer surface. The sample is obtained from the margin and the base. The material obtained is smeared onto one or two glass slides for microscopic evaluation along with a Gram stain. An upper side surface is provided on the slide for labeling with a pen or a pencil as a convention. The sample is allowed to dry and then placed on the slide carrier. Repeat scraping is performed, and the sample is placed on various culture media like blood agar, chocolate agar, potato dextrose agar, brain heart infusion broth, Lowenstein Jansen media, etc. If the patient has previously used antibiotics, scraping can be delayed for at least 12 hours. Recently calcium alginate swabs with trypticase soy broth have been employed to obtain corneal specimens for obtaining a higher yield of bacteria. We have to be careful while obtaining specimens in case of corneal melt, descemetocele, and deep stromal keratitis cases.[40]

The culture agar media is inoculated in the form of conventional multiple C markings without cutting the agar. In liquid media, the spatula or needle is dipped in the media deeply.

Various Strains Used for Bacteria

- Gram stain - gram-positive bacteria appear purple and gram-negative as pink.

- Acridine orange - Bacteria appear as yellow-green

- Acid Fast - Mycobacterium appear as pink

Various Culture Media for Bacteria

- Blood agar (35 degrees) - Aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria

- Chocolate agar (35 degrees) - Aerobic, anaerobic, Neisseria, Moraxella and Haemophilus

- Thioglycolate broth (35 degrees) - Aerobic bacteria and anaerobic bacteria

- Sabouraud’s dextrose agar (Room temperature) - Nocardia

- Brain heart infusion broth (Room temperature) - Nocardia

- Middlebrook Cohn agar (35 degree with 3 to 10% CO2) - Mycobacterium and Nocardia

- Cooked meat broth (35 degrees) - Anaerobic bacteria

- Thayer martin blood agar (35 degrees) - Neisseria

- Lowenstein Jensen media (35 degrees with 3 to 10% CO2) - Mycobacterium species[41]

Modified Jones severity grading of bacterial keratitis[1]

|

|

Mild

|

Moderate

|

Severe

|

|

Size

|

<2 mm

|

2-5 mm

|

>5 mm

|

|

Depth

|

< 20 percent

|

20-50 percent

|

>50 percent

|

|

Infiltrate

|

Superficial

|

Extends to mid stroma

|

Deep stromal

|

|

Scleral involvement

|

Not present

|

Not present

|

May be involved

|

Jones Criteria for Culture Positivity

- Clinically infective ulcer plus the isolation of bacteria (colony count 10 or more) on one solid and one additional culture media

- Isolation of bacteria on any two solid media

- Isolation of bacteria in on one media along with positive scraping[42]

Conjunctival Swab Culture

In severe cases when culture growth is negative, conjunctival swab culture can be a vital adjunctive diagnostic modality. Calcium alginate swans yield the best results.[43]

Contact Lens Culture

Contact lens, solution and, cases can also be cultured to yield significant information provided they have not been cleaned by the patient.[44]

Culture and Sensitivity Reports

Culture and sensitivity reports help in targeted antibacterial therapy. It also helps in determining bacterial antibiotic resistance and susceptibility. Sometimes the clinician needs to switch between antibiotic regimens based on antibiotic sensitivity reports.[45]

Paracentesis

Anterior chamber paracentesis is sometimes needed when scraping where cultures and negative, and there is a progression of ulcer despite best antibacterial therapy. It will also assist in distinguishing bacterial from other microbial keratitis cases. A side port is made, and a 0.1 to 0.2 ml sample is obtained with the help of a 25 G needle.[46]

Corneal Biopsy

A corneal biopsy is performed when smear and culture results are negative two times, and there is a clinical progression of ulcer despite best antibacterial therapy. It is obtained with the help of a poly filament braided 6-0 or 8-0 silk sutures from normal to abnormal areas.[47]

Ultrasound B Scan

It is usually performed after therapeutic keratoplasty when the fundus evaluation is not possible due to corneal edema, haze, fibrinous membrane, hyphema, or exudates in the anterior chamber. This diagnostic modality helps rule out retinal detachment, choroidal detachment, endophthalmitis, panophthalmitis, nucleus or lens drops, and vitritis.

Newer Diagnostic Modalities

Immunohistochemistry, enzyme immunoassay, polymerase chain reaction, and radioimmunoassay are recent upcoming modalities but still have a limited role in diagnosing bacterial keratitis.[48]

Treatment / Management

Medical Treatment

The medical treatment should be immediately started once the patient presents to the clinician. The smear results are usually available within 1 hour. After obtaining the smear results, the patient should start on broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, covering both gram-positive and negative bacteria. Once the culture results are available after 48 to 72 hours, the treatment must be switched to targeted antibacterial therapy. In peripheral ulcers not involving the visual axis (<3mm), monotherapy is initiated. In the case of larger and deep stromal ulcers, it is better to start two antibacterial to prevent irreversible vision-threatening sequelae.[49]

Topical Antibiotics

Cephalosporins

The most common drug implicated is topical cefazolin 5% (fortified). It is best suitable for non-penicillinase-producing gram-positive bacteria.

Aminoglycosides

Fortified topical tobramycin 0.3%, gentamicin 0.3%, and amikacin 1g/ml injection are very effective against gram-negative bacteria, streptococci, and staphylococci but have a very limited response against pneumococci. Fortified cefazolin and tobramycin are available commercially as a combination which is one of the most commonly implicated drugs in bacterial keratitis.

Glycopeptides

Fortified vancomycin 5% is very active against methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Fluoroquinolones

The drugs available are 0.3% ciprofloxacin, 0.3% ofloxacin, 0.5% moxifloxacin and 0.3 % gatifloxacin. They are primarily instilled as monotherapy. Recently growing resistance is noted for ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin; hence moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin are being used with more efficacy in managing bacterial keratitis.[50]

Systemic Antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics have a limited role in the management of bacterial keratitis. The only indications are scleritis, endophthalmitis, or non-resolving progressive bacterial ulcers. The drugs implicated are ciprofloxacin 750 mg BD or an aminoglycoside with cephalosporin.[51]

Cycloplegics

Cycloplegics are employed as adjuvant drugs for reducing ciliary spasm, pain, posterior synechiae, reduce cells and flare, and helps in the migration of antibodies to the aqueous humor. It also helps in increasing the blood flow to anterior uveal tissue by alleviating pressure on arteries.

Antiglaucoma Drugs

Antiglaucoma drugs are a useful adjunctive modality for controlling intraocular pressure. They help drain the hypopyon by opening the trabecular meshwork and drainage channels, reducing intraocular pressure. Moreover, they also help in controlling trabeculitis secondary to the inflammatory process. The safest drug is 0.5 % timolol BD. Miotics and prostaglandin analogs should be avoided as they are known to aggravate inflammation.

Lubricating Eye Drops

These drugs help epithelial healing, reduce irritation, wash away debris and necrotic enzymes, and smoothen the ocular surface and cornea. The commonly implicated drugs are topical 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose and 0.3% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose.

Systemic Anti-inflammatory Drugs

These drugs help to reduce pain and inflammation. The commonly used are 50 mg diclofenac with 10 mg serratiopeptidase BD combination and 200 mg ibuprofen BD.

Protective Measures

Besides the targeted therapy, equally, importance must be given to protective measures like using dark goggles, preventing direct exposure to sunlight, excessive eye rubbing, applying soap or direct water splash in the eyes, rest, good and timely diet, and hot fomentation.

Surgical Treatment

Gunderson Flap

This treatment is beneficial when a donor cornea is not available to salvage a perforated corneal ulcer. The upper conjunctiva is dissected, and a thin flap of the conjunctiva is covered over the cornea and sutured. It acts as metabolic support for the cornea.[52]

Therapeutic Penetrating Keratoplasty (TPK)

The treatment of choice for non-healing corneal ulcers (2 weeks) is TPK. TPK helps eliminate the focus of infection and is essential for restoring anatomical integrity in perforated corneal ulcers (tectonic keratoplasty). In TPK, the host diseased cornea is replaced by a healthy donor corneal button of appropriate size. Initially, trephination of the host cornea is performed, taking a 0.5 mm margin clearance from the diseased cornea. The graft is kept 0.5 mm larger than the trephined host cornea.

This process is followed by removing exudates from the anterior chamber and angle, the release of peripheral anterior synechiae, peripheral iridectomy, and the lens is removed if needed. The lens removal is done when the lens is cataractous, or exudates are present in the lens. If the posterior capsule remains intact and meticulous exudate removal is complete, the graft is sutured to the host bed with 16 interrupted 9-0 or 10-0 nylon sutures. If the posterior capsule is breached, a thorough anterior vitrectomy is mandated with quick closure of the eye to prevent expulsive choroidal hemorrhage as it is an open sky procedure. Some surgeons also prefer to use continuous sutures.[53]

Penetrating Keratoplasty (PKP)

This is indicated once the cornea has scarred and healed and the infective foci have been eliminated. The PKP is performed similar to that of TPK, ensuring perfect graft host junction opposition and maintaining the radiality of sutures. The PKP aims to restore the patient's vision and should be performed after taking all necessary precautions. If the lens is cataractous, a triple procedure in the form of PKP, cataract extraction, and IOL implantation should be considered. The PKP is usually performed after 6 to 8 months of quiescence.[53]

Management of Impending Perforation and Perforation

The treatment of perforation is cyanoacrylate glue application along with bandage contact lens (BCL). The patient should be instructed to avoid excessive coughing or straining. The other option is amniotic membrane grafting (AMG). Larger perforation (>2mm) should be taken up for therapeutic keratoplasty.[54]

Signs of Good Response to Treatment

- Reduction in ulcer size

- Blunting of ulcer margins

- Reduction of pain, photophobia, lid edema, and discharge

- Healing of epithelial defect

- Resolution of hypopyon

- Improvement in visual acuity

- Vascularization[55]

Signs of unfavorable response to treatment

- Worsening of symptoms

- Increased size of ulcer and more feathery margins

- Stromal thinning

- Increase endoexudates and hypopyon

- Nonhealing epithelial defect

- Stromal thinning

- Scleral involvement and infiltration of the limbus[55]

Differential Diagnosis

Infective

- Fungal keratitis

- Pythium keratitis

- Viral keratitis

- Neurotrophic keratitis

- Neuroparalytic keratitis

- Interstitial keratitis

- Disciform keratitis

- Acanthamoeba keratitis

- Exposure keratopathy

- Chemical Injury

- Thermal keratitis

- Atopic keratoconjunctivitis

- Shield ulcer

- Rosacea keratitis

Non- infective

- Peripheral Ulcerative keratitis

- Marginal keratitis

- Mooren’s Ulcer

- Toxic keratitis

- Sterile inflammatory corneal infiltrate

Prognosis

The prognosis of bacterial keratitis is governed by a multitude of factors. If the ulcer involves superficial corneal layers till the anterior one-third of the stroma, the chance of healing and prognosis is good. Ulcer involving more than two-third of stroma, involving visual axis, stromal melt, and corneal thinning usually have a bad prognosis. The other determinants of prognosis are regular use of medications, compliance, involvement of sclera or endophthalmitis, regular follow up and counseling.

Complications

- Corneal scarring

- Corneal melt

- Corneal anesthesia

- Neurotrophic keratopathy

- Descemetocele

- Perforation

- Secondary glaucoma

- Neovascular glaucoma[56]

- Iris Neovascularization

- Hyphema

- Hemorrhage

- Toxic iridocyclitis

- Subluxation of lens[57][58]

- Anterior subcapsular cataract[59][60]

- Corneal fistula

- Scleritis

- Retinal detachment

- Choroidal detachment

- Endophthalmitis

- Panophthalmitis

- Keratectasia

- Atrophic bulbi

- Autoevisceration

- Phthisis bulbi

Surgical Complications

- Wound leak

- Irregular trephination

- Small size graft

- Secondary glaucoma

- Flat anterior chamber

- Iridodialysis

- Pupillary block

- Expulsive choroidal hemorrhage

- Retinal detachment

- Choroidal detachment

- Vitreous hemorrhage

Suture Related Complications

- Vascularization

- Infection

- Loose sutures

- Wound leak

- Exposed knots

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Counseling and regular follow-up are important for a good postoperative outcome. The patient should instill hourly antibiotic eyedrops for 48 hours to 1 week. Based on the clinical response, the drug is tapered. In the case of a large ulcer involving the visual axis, it is always better to start two antibacterials hourly. If the response is good, the same drug is continued; in case of a poor response, it is better to revise the diagnosis. The adjuvants are added with the antibacterials for an additive effect and quick clinical response.

The patient must understand the drug regimen and the importance of using each drug. After 3 to 4 weeks of being infection-free post keratoplasty, the patient can switch to topical steroids for graft survival. The steroid regimen should be 4/3/2/1 times for three months each with regular and timely follow-up. It is important to add 0.5 % timolol BD to prevent secondary cataracts and glaucoma in these patients. The sutures can be removed as they become loose or after at least 12 months.

Consultations

Any patient with bacterial keratitis presenting to the emergency ophthalmology outpatient department must be evaluated carefully with a high index of clinical suspicion. All the patients must be referred to a cornea and external disease specialist for correct diagnosis and targeted antibacterial therapy. If treated on time, these vision-threatening ulcers can have an excellent visual outcome.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Based on their clinical presentation, all patients with bacterial keratitis must receive education regarding the pathology and the long-term prognosis. The patient must be educated to avoid risk factors like contact lens use and other provoking factors like alcohol and malnutrition. The use of google and protective eyewear requires emphasis. Equally vital is patient education regarding regular use of medications and timely follow-up. The patient should also be educated regarding the need for TPK in the future and the complications associated with the surgical intervals. The patient should be educated that TPK will be necessary for eliminating the infectious foci and anatomical stabilization of the globe. The functional or visual outcome will depend on penetrating keratoplasty later, and the patient should have realistic expectations considering vision.

Pearls and Other Issues

So, in a nutshell, bacterial keratitis is a disease prevalent in the underdeveloped and developing worlds. The most important risk factor is trauma in the Indian scenario and contact lenses in the west. The diagnosis rests on a high index of clinical suspicion assisted by laboratory investigations. Early diagnosis, meticulous management, and timely and regular follow-up are key determinants of success in these cases. The superficial ulcer usually responds well to medical management, whereas deeper non-resolving ulcers require TPK for globe salvage. A timely performed TPK in skilled hands can have excellent outcomes. Patients with corneal scar post ulcer resolution can be taken for PKP for visual restoration.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bacterial keratitis is a significant cause of vision-threatening keratitis across the globe. Prompt diagnosis, meticulous management, regular and close follow can salvage vision in these patients. The ophthalmologists are responsible for clinching the pinpoint diagnosis and targeted antibacterial therapy. The optometrists play a key role in the preliminary diagnosis and referral of these patients to cornea and external disease specialists. The nursing team also plays an instrumental role in counseling these patients regarding contact lens hygiene, use, frequency, educating the patients regarding signs and symptoms of bacterial keratitis. The nursing team also guides these patients regarding the frequency and dose of antibacterials to be used at home. The pharmacists also help in procuring the drugs for these patients. Hence, in a nutshell, the interprofessional teamwork of all paramedical staff and the treating ophthalmologists determines the functional and anatomical in these patients. If treated in a timely fashion, bacterial keratitis patients can have good outcomes, which is a benefit for any patient for their day-to-day living.