[1]

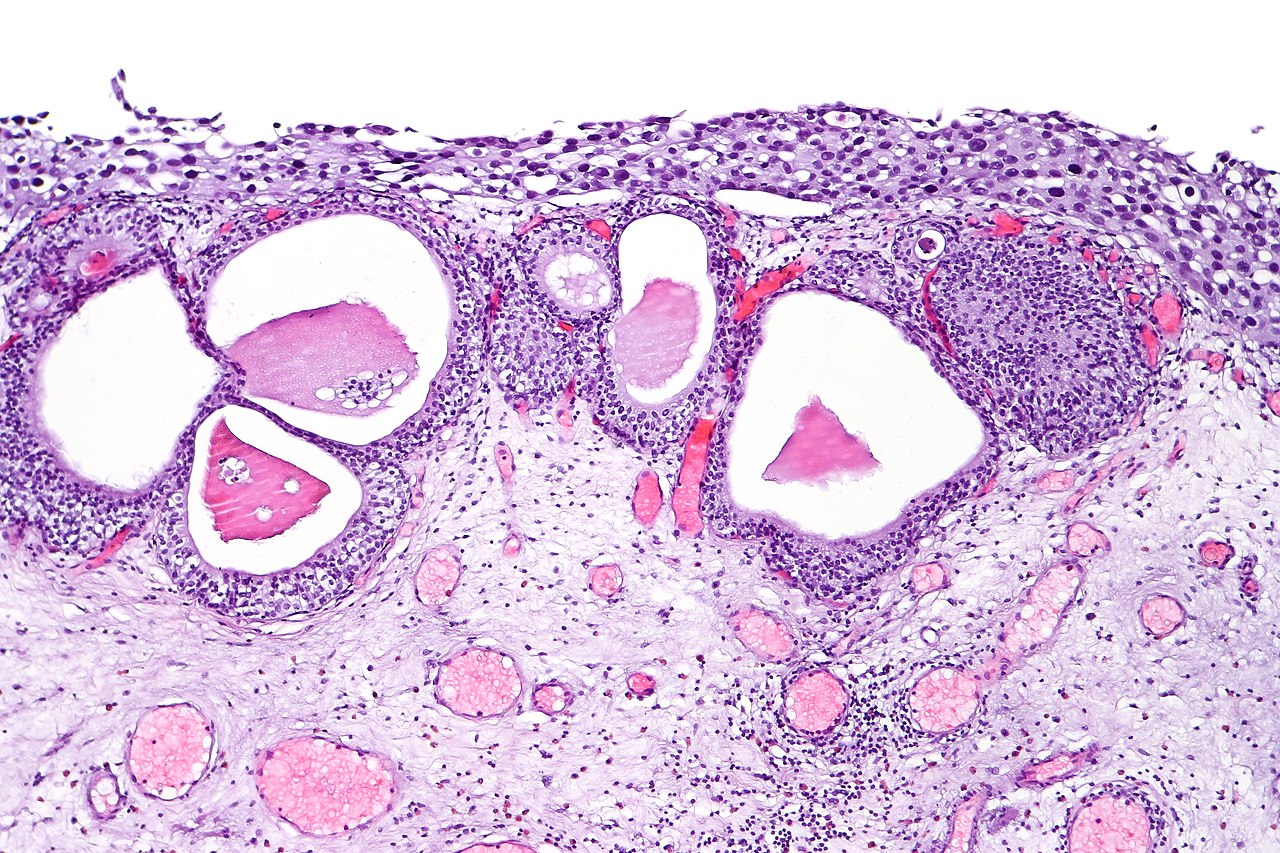

Eastman R Jr, Leaf EM, Zhang D, True LD, Sweet RM, Seidel K, Siebert JR, Grady R, Mitchell ME, Bassuk JA. Fibroblast growth factor-10 signals development of von Brunn's nests in the exstrophic bladder. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2010 Nov:299(5):F1094-110. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00056.2010. Epub 2010 Aug 18

[PubMed PMID: 20719973]

[2]

Xin Z, Zhao C, Huang T, Zhang Z, Chu C, Lu C, Wu M, Zhou W. Intestinal metaplasia of the bladder in 89 patients: a study with emphasis on long-term outcome. BMC urology. 2016 Jun 7:16(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12894-016-0142-x. Epub 2016 Jun 7

[PubMed PMID: 27267922]

[3]

Yi X, Lu H, Wu Y, Shen Y, Meng Q, Cheng J, Tang Y, Wu F, Ou R, Jiang S, Bai X, Xie K. Cystitis glandularis: A controversial premalignant lesion. Oncology letters. 2014 Oct:8(4):1662-1664

[PubMed PMID: 25202387]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[4]

Manini C, Angulo JC, López JI. Mimickers of Urothelial Carcinoma and the Approach to Differential Diagnosis. Clinics and practice. 2021 Feb 25:11(1):110-123. doi: 10.3390/clinpract11010017. Epub 2021 Feb 25

[PubMed PMID: 33668963]

[5]

Venyo AK. Nephrogenic Adenoma of the Urinary Bladder: A Review of the Literature. International scholarly research notices. 2015:2015():704982. doi: 10.1155/2015/704982. Epub 2015 Feb 2

[PubMed PMID: 27347540]

[6]

Santi R, Angulo JC, Nesi G, de Petris G, Kuroda N, Hes O, López JI. Common and uncommon features of nephrogenic adenoma revisited. Pathology, research and practice. 2019 Oct:215(10):152561. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152561. Epub 2019 Jul 25

[PubMed PMID: 31358481]

[7]

Bannoura S, Putra J. Bladder Exstrophy Polyp: An Uncommon Entity in Surgical Pathology. Fetal and pediatric pathology. 2022 Jun:41(3):523-525. doi: 10.1080/15513815.2020.1854401. Epub 2020 Nov 30

[PubMed PMID: 33252291]

[8]

Liu X, Chen Z, Ye Z. Etiological study on cystitis glandularis caused by bacterial infection. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Medical sciences = Hua zhong ke ji da xue xue bao. Yi xue Ying De wen ban = Huazhong keji daxue xuebao. Yixue Yingdewen ban. 2007 Dec:27(6):678-80. doi: 10.1007/s11596-007-0615-y. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18231741]

[9]

Chen Z, Ye Z, Zeng W. Clinical investigation on the correlation between lower urinary tract infection and cystitis glandularis. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Medical sciences = Hua zhong ke ji da xue xue bao. Yi xue Ying De wen ban = Huazhong keji daxue xuebao. Yixue Yingdewen ban. 2004:24(3):303-4

[PubMed PMID: 15315357]

[10]

Kao CS, Kum JB, Fan R, Grignon DJ, Eble JN, Idrees MT. Nephrogenic adenomas in pediatric patients: a morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 21 cases. Pediatric and developmental pathology : the official journal of the Society for Pediatric Pathology and the Paediatric Pathology Society. 2013 Mar-Apr:16(2):80-5. doi: 10.2350/12-10-1261-OA.1. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23597251]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[11]

Mazal PR, Schaufler R, Altenhuber-Müller R, Haitel A, Watschinger B, Kratzik C, Krupitza G, Regele H, Meisl FT, Zechner O, Kerjaschki D, Susani M. Derivation of nephrogenic adenomas from renal tubular cells in kidney-transplant recipients. The New England journal of medicine. 2002 Aug 29:347(9):653-9

[PubMed PMID: 12200552]

[12]

Wiener DP, Koss LG, Sablay B, Freed SZ. The prevalence and significance of Brunn's nests, cystitis cystica and squamous metaplasia in normal bladders. The Journal of urology. 1979 Sep:122(3):317-21

[PubMed PMID: 470001]

[13]

Kunju LP. Nephrogenic adenoma: report of a case and review of morphologic mimics. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2010 Oct:134(10):1455-9

[PubMed PMID: 20923300]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[14]

Manini C, López JI. Unusual Faces of Bladder Cancer. Cancers. 2020 Dec 10:12(12):. doi: 10.3390/cancers12123706. Epub 2020 Dec 10

[PubMed PMID: 33321728]

[15]

Zhong M, Tian W, Zhuge J, Zheng X, Huang T, Cai D, Zhang D, Yang XJ, Argani P, Fallon JT, Epstein JI. Distinguishing nested variants of urothelial carcinoma from benign mimickers by TERT promoter mutation. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015 Jan:39(1):127-31. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000305. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25118812]

[16]

Williamson SR, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Cheng L. Glandular lesions of the urinary bladder:clinical significance and differential diagnosis. Histopathology. 2011 May:58(6):811-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03651.x. Epub 2010 Sep 21

[PubMed PMID: 20854477]

[17]

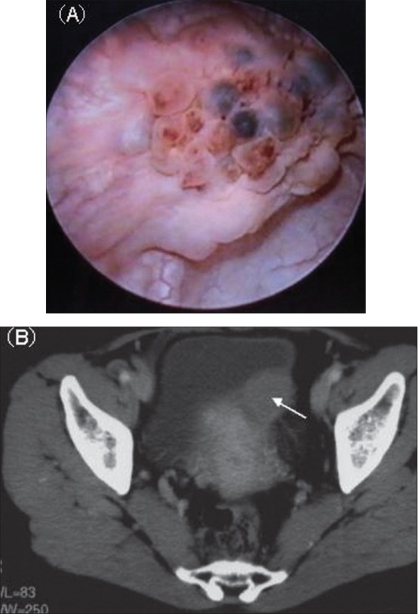

Lin HY, Wu WJ, Jang MY, Shen JT, Tsai HN, Chou YH, Huang CH. Cystitis glandularis mimics bladder cancer--three case reports and literature review. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences. 2001 Feb:17(2):102-6

[PubMed PMID: 11416957]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[18]

SHAW JL, GISLASON GJ, IMBRIGLIA JE. Transition of cystitis glandularis to primary adenocarcinoma of the bladder. The Journal of urology. 1958 May:79(5):815-22

[PubMed PMID: 13539968]

[19]

Lin JI, Yong HS, Tseng CH, Marsidi PS, Choy C, Pilloff B. Diffuse cystitis glandularis. Associated with adenocarcinomatous change. Urology. 1980 Apr:15(4):411-5

[PubMed PMID: 7394970]

[20]

García Rojo D, Prera Vilaseca A, Sáez Artacho A, Abad Gairín C, Prats López J, Rosa Bella Cueto M. [Transformation of glandular cystitis into bladder transitional carcinoma with adenocarcinoma areas]. Archivos espanoles de urologia. 1997 Mar:50(2):187-9

[PubMed PMID: 9206946]

[21]

Thrasher JB, Rajan RR, Perez LM, Humphrey PA, Anderson EE. Cystitis glandularis. Transition to adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder. North Carolina medical journal. 1994 Nov:55(11):562-4

[PubMed PMID: 7808523]

[22]

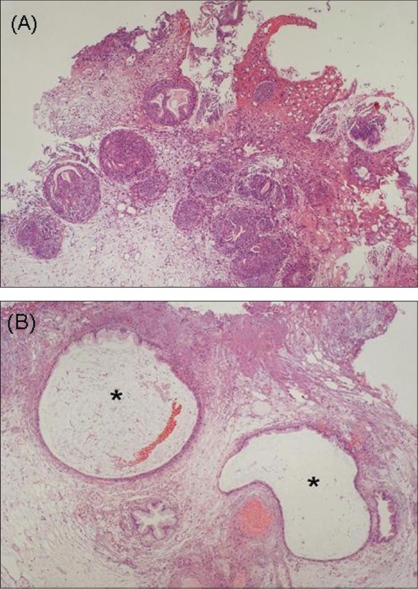

Popov H, Stoyanov GS, Ghenev P. Intestinal-Type Adenocarcinoma of the Urinary Bladder With Coexisting Cystitis Cystica et Glandularis and Intestinal Metaplasia: A Histopathological Case Report. Cureus. 2023 Mar:15(3):e36554. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36554. Epub 2023 Mar 22

[PubMed PMID: 37102004]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[23]

Agrawal A, Kumar D, Jha AA, Aggarwal P. Incidence of adenocarcinoma bladder in patients with cystitis cystica et glandularis: A retrospective study. Indian journal of urology : IJU : journal of the Urological Society of India. 2020 Oct-Dec:36(4):297-302. doi: 10.4103/iju.IJU_261_20. Epub 2020 Oct 1

[PubMed PMID: 33376267]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[24]

Smith AK, Hansel DE, Jones JS. Role of cystitis cystica et glandularis and intestinal metaplasia in development of bladder carcinoma. Urology. 2008 May:71(5):915-8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.079. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18455631]

[25]

Gordetsky J, Epstein JI. Intestinal metaplasia of the bladder with dysplasia: a risk factor for carcinoma? Histopathology. 2015 Sep:67(3):325-30. doi: 10.1111/his.12661. Epub 2015 Mar 8

[PubMed PMID: 25640978]

[26]

Li A, Zhou J, Lu H, Zuo X, Liu S, Zhang F, Li W, Fang W, Zhang B. Pathological feature and immunoprofile of cystitis glandularis accompanied with upper urinary tract obstruction. BioMed research international. 2014:2014():872170. doi: 10.1155/2014/872170. Epub 2014 May 29

[PubMed PMID: 25136635]

[27]

Diolombi M, Ross HM, Mercalli F, Sharma R, Epstein JI. Nephrogenic adenoma: a report of 3 unusual cases infiltrating into perinephric adipose tissue. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2013 Apr:37(4):532-8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826f0447. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23426119]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[28]

Tong GX, Melamed J, Mansukhani M, Memeo L, Hernandez O, Deng FM, Chiriboga L, Waisman J. PAX2: a reliable marker for nephrogenic adenoma. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2006 Mar:19(3):356-63

[PubMed PMID: 16400326]

[29]

Oliva E, Young RH. Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: a review of the microscopic appearance of 80 cases with emphasis on unusual features. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 1995 Sep:8(7):722-30

[PubMed PMID: 8539229]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[30]

Cheng L, Cheville JC, Sebo TJ, Eble JN, Bostwick DG. Atypical nephrogenic metaplasia of the urinary tract: a precursor lesion? Cancer. 2000 Feb 15:88(4):853-61

[PubMed PMID: 10679655]

[31]

López JI, Schiavo-Lena M, Corominas-Cishek A, Yagüe A, Bauleth K, Guarch R, Hes O, Tardanico R. Nephrogenic adenoma of the urinary tract: clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical characteristics. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. 2013 Dec:463(6):819-25. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1497-y. Epub 2013 Oct 19

[PubMed PMID: 24142157]

[32]

Sharifai N, Abro B, Chen JF, Zhao M, He H, Cao D. Napsin A is a highly sensitive marker for nephrogenic adenoma: an immunohistochemical study with a specificity test in genitourinary tumors. Human pathology. 2020 Aug:102():23-32. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2020.05.007. Epub 2020 Jun 17

[PubMed PMID: 32561332]

[33]

McDaniel AS, Chinnaiyan AM, Siddiqui J, McKenney JK, Mehra R. Immunohistochemical staining characteristics of nephrogenic adenoma using the PIN-4 cocktail (p63, AMACR, and CK903) and GATA-3. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2014 Dec:38(12):1664-71. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000267. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24921643]

[34]

Mihai I, Taban S, Cumpanas A, Olteanu EG, Iacob M, Dema A. Clear cell urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder - a rare pathological entity. A case report and a systematic review of the literature. Bosnian journal of basic medical sciences. 2019 Nov 8:19(4):400-403. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2019.4182. Epub 2019 Nov 8

[PubMed PMID: 30957722]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[35]

Son Y, Madison I, Scali J, Chialastri P, Brown G. Cystitis Cystica Et Glandularis Causing Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in a 29-Year-Old Male. Cureus. 2021 Aug:13(8):e17144. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17144. Epub 2021 Aug 13

[PubMed PMID: 34548967]

[36]

Kaya C, Akpinar IN, Aker F, Turkeri LN. Large Cystitis glandularis: a very rare cause of severe obstructive urinary symptoms in an adult. International urology and nephrology. 2007:39(2):441-4

[PubMed PMID: 17171414]

[37]

el Moussaoui A, Dakir M, Sarf I, Aboutaieb R, Zamiati S, Benjelloun S. [Cystitis cystica glandularis. A study of 2 cases]. Annales d'urologie. 1997:31(4):195-8

[PubMed PMID: 9412342]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[38]

Potts S, Calleary J. Cystitis Cystica as a Large Solitary Bladder Cyst. Journal of endourology case reports. 2017:3(1):34-38. doi: 10.1089/cren.2017.0010. Epub 2017 Mar 1

[PubMed PMID: 28466074]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[39]

Leopold BH, Johnson CM, Makai GEH. Cystitis Cystica on Routine Cystoscopy at Time of Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2019 Sep-Oct:26(6):999. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.02.001. Epub 2019 Feb 6

[PubMed PMID: 30735732]

[40]

Jeon J, Ha JS, Shin SJ, Ham WS, Choi YD, Cho KS. Differences in clinical features between focal and extensive types of cystitis glandularis in patients without a previous history of urinary tract malignancy. Investigative and clinical urology. 2023 Nov:64(6):597-605. doi: 10.4111/icu.20230210. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 37932571]

[42]

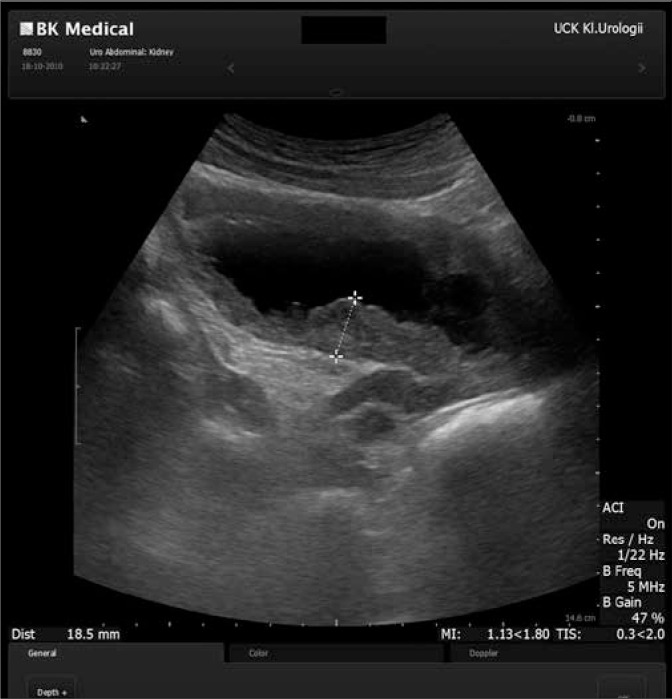

Milosević D, Batinic D, Vrljicak K, Skitarelić N, Potkonjak AM, Turudić D, Bambir I, Roić AC, Spajić M, Spajić B. Ultrasound distinction between simple recurrent urinary tract infections and a specific bladder wall inflammatory entity called cystitis cystica. Collegium antropologicum. 2014 Mar:38(1):151-4

[PubMed PMID: 24851610]

[43]

Milošević D, Trkulja V, Turudić D, Batinić D, Spajić B, Tešović G. Ultrasound bladder wall thickness measurement in diagnosis of recurrent urinary tract infections and cystitis cystica in prepubertal girls. Journal of pediatric urology. 2013 Dec:9(6 Pt B):1170-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.04.019. Epub 2013 May 30

[PubMed PMID: 23725853]

[44]

Vrljicak K, Milosević D, Batinić D, Kniewald H, Nizić L. The significance of ultrasonography in diagnosing and follow-up of cystic cystitis in children. Collegium antropologicum. 2006 Jun:30(2):355-9

[PubMed PMID: 16848151]

[45]

Sureka B, Jain V, Jain S, Rastogi A. Cystitis Cystica Glandularis: Radiological Imitator of Urothelial Carcinoma. Iranian journal of kidney diseases. 2018 Jan:12(1):10

[PubMed PMID: 29421770]

[47]

Reddy M, Zimmern PE. Efficacy of antimicrobial intravesical treatment for uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections: a systematic review. International urogynecology journal. 2022 May:33(5):1125-1143. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-05042-z. Epub 2022 Jan 4

[PubMed PMID: 34982189]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[48]

Jepson RG, Williams G, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012 Oct 17:10(10):CD001321. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub5. Epub 2012 Oct 17

[PubMed PMID: 23076891]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[49]

Milosević D, Batinić D, Tesović G, Konjevoda P, Kniewald H, Subat-Dezulović M, Grković L, Topalović-Grković M, Turudić D, Spajić B. Cystitis cystica and recurrent urinary tract infections in children. Collegium antropologicum. 2010 Sep:34(3):893-7

[PubMed PMID: 20977079]

[50]

De Nunzio C, Bartoletti R, Tubaro A, Simonato A, Ficarra V. Role of D-Mannose in the Prevention of Recurrent Uncomplicated Cystitis: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Apr 1:10(4):. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10040373. Epub 2021 Apr 1

[PubMed PMID: 33915821]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[52]

Chiu K, Zhang F, Sutcliffe S, Mysorekar IU, Lowder JL. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection Incidence Rates Decrease in Women With Cystitis Cystica After Treatment With d-Mannose: A Cohort Study. Female pelvic medicine & reconstructive surgery. 2022 Mar 1:28(3):e62-e65. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001144. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 35272335]

[53]

Dason S, Dason JT, Kapoor A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2011 Oct:5(5):316-22. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11214. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22031610]

[54]

Stamm WE, Counts GW, Wagner KF, Martin D, Gregory D, McKevitt M, Turck M, Holmes KK. Antimicrobial prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Annals of internal medicine. 1980 Jun:92(6):770-5

[PubMed PMID: 6992677]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[55]

Price JR, Guran LA, Gregory WT, McDonagh MS. Nitrofurantoin vs other prophylactic agents in reducing recurrent urinary tract infections in adult women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Nov:215(5):548-560. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.040. Epub 2016 Jul 22

[PubMed PMID: 27457111]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[56]

Jent P, Berger J, Kuhn A, Trautner BW, Atkinson A, Marschall J. Antibiotics for Preventing Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Open forum infectious diseases. 2022 Jul:9(7):ofac327. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac327. Epub 2022 Jul 3

[PubMed PMID: 35899289]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[57]

Alghoraibi H, Asidan A, Aljawaied R, Almukhayzim R, Alsaydan A, Alamer E, Baharoon W, Masuadi E, Al Shukairi A, Layqah L, Baharoon S. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection in Adult Patients, Risk Factors, and Efficacy of Low Dose Prophylactic Antibiotics Therapy. Journal of epidemiology and global health. 2023 Jun:13(2):200-211. doi: 10.1007/s44197-023-00105-4. Epub 2023 Jun 5

[PubMed PMID: 37273158]

[59]

Yuksel OH, Urkmez A, Erdogru T, Verit A. The role of steroid treatment in intractable cystitis glandularis: A case report and literature review. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2015 May-Jun:9(5-6):E306-9. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.2636. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26029302]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[60]

Koyama J, Namiki S, Kudo T, Aizawa M, Ioritani N, Nakamura Y. [TYPICAL TYPE CYSTITIS GLANDULARIS PRESENTING URINARY RETENTION IN A YOUNG MAN: ADJUVANT THERAPY USING ORAL CYCLOOXYGENASE-2 INHIBITOR: A CASE REPORT]. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai zasshi. The japanese journal of urology. 2019:110(2):148-151. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol.110.148. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32307385]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[61]

Ni Y, Zhao S, Yin X, Wang H, Guang Q, Hu G, Yang Y, Jiao S, Shi B. Intravesicular administration of sodium hyaluronate ameliorates the inflammation and cell proliferation of cystitis cystica et glandularis involving interleukin-6/JAK2/Stat3 signaling pathway. Scientific reports. 2017 Nov 21:7(1):15892. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16088-9. Epub 2017 Nov 21

[PubMed PMID: 29162939]

[62]

Klingler CH. Glycosaminoglycans: how much do we know about their role in the bladder? Urologia. 2016 Jun 25:83 Suppl 1():11-4. doi: 10.5301/uro.5000184. Epub 2016 Jun 23

[PubMed PMID: 27405344]

[63]

Boucher WS, Letourneau R, Huang M, Kempuraj D, Green M, Sant GR, Theoharides TC. Intravesical sodium hyaluronate inhibits the rat urinary mast cell mediator increase triggered by acute immobilization stress. The Journal of urology. 2002 Jan:167(1):380-4

[PubMed PMID: 11743360]

[64]

Madurga Patuel B, González-López R, Resel Folkersma L, Machado Fernández G, Adot Zurbano JM, Bonillo MÁ, Vozmediano Chicharro R, Zubiaur Líbano C. Recommendations on the use of intravesical hyaluronic acid instillations in bladder pain syndrome. Actas urologicas espanolas. 2022 Apr:46(3):131-137. doi: 10.1016/j.acuroe.2022.02.007. Epub 2022 Mar 4

[PubMed PMID: 35256323]

[65]

Samdal F, Brevik B, Halgunset J. Cystitis cystica treated with the neodymium-YAG laser. Case report. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology. 1991:25(2):163-4

[PubMed PMID: 1871562]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[66]

Shen YC, Tyagi P, Lee WC, Chancellor M, Chuang YC. Improves symptoms and urinary biomarkers in refractory interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome patients randomized to extracorporeal shock wave therapy versus placebo. Scientific reports. 2021 Apr 6:11(1):7558. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87040-1. Epub 2021 Apr 6

[PubMed PMID: 33824389]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[67]

Nasrallah OG, Balaghi A, El Sayegh N, Mahdi JH, Sinno S, Nasr RW. Florid Cystitis Glandularis with Intestinal Metaplasia in the Prostatic Urethra: a case report and review of the literature. International journal of surgery case reports. 2024 Mar:116():109416. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2024.109416. Epub 2024 Feb 28

[PubMed PMID: 38422750]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[68]

Heidenreich A, Zirbes TK, Wolter S, Engelmann UH. Nephrogenic adenoma: A rare bladder tumor in children. European urology. 1999 Oct:36(4):348-53

[PubMed PMID: 10473997]

[69]

Voss K, Peppas D. Recurrent nephrogenic adenoma: a case report of resolution after treatment with antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Urology. 2013 Nov:82(5):1156-7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.04.024. Epub 2013 Jun 20

[PubMed PMID: 23791211]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[70]

Santoni N, Cottrell L, Talia Jones JE, Bekarma HJ. Multifocal nephrogenic adenoma treated by intravesical sodium hyaluronate. Urology annals. 2020 Apr-Jun:12(2):187-189. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_74_19. Epub 2020 Apr 14

[PubMed PMID: 32565661]

[71]

Yi Y, Wu A, Cameron AP. Nephrogenic adenoma of the bladder: a single institution experience assessing clinical factors. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. 2018 May-Jun:44(3):506-511. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2017.0155. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29493186]

[72]

Vuckov S, Subat-Dezulović M, Nikolić H. [Relation between successful treatment of urinary tract inflammation and the disappearance of changes in the bladder mucosa in children and adolescents with cystoscopically proven cystitis cystica]. Lijecnicki vjesnik. 1997 Nov:119(10):266-9

[PubMed PMID: 9531758]

[73]

Vrljicak K, Turudić D, Bambir I, Gradiski IP, Spajić B, Batinić D, Topalović-Grković M, Spajić M, Batinić D, Milosević D. Positive feedback loop for cystitis cystica: the effect of recurrent urinary tract infection on the number of bladder wall mucosa nodules. Acta clinica Croatica. 2013 Dec:52(4):444-7

[PubMed PMID: 24696993]

[74]

Maeda M, Hirabayashi T, Inuzuka Y, Kondo A, Tanaka K. [Case of cystitis glandularis causing bilateral hydronephrosis]. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai zasshi. The japanese journal of urology. 2013 Sep:104(5):671-3

[PubMed PMID: 24187856]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[75]

Abasher A, Abdel Raheem A, Aldarrab R, Aldurayhim M, Attallah A, Banihani O. Bladder outlet obstruction secondary to posterior urethral cystitis cystica & glandularis in a 12-year-old boy. A rare case scenario. Urology case reports. 2020 Nov:33():101425. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2020.101425. Epub 2020 Sep 23

[PubMed PMID: 33102121]

[76]

Suzuki T, Furuse H, Matsumoto R, Ito T, Sugiyama T, Nagata M, Otsuka A, Takayama T, Mugiya S, Ozono S. [A case of proliferative cystitis forming ureterovesical junction obstruction]. Hinyokika kiyo. Acta urologica Japonica. 2011 Oct:57(10):573-6

[PubMed PMID: 22089157]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[77]

Ge B, Guo C, Liang Y, Liu M, Wu K. Network analysis, and human and animal studies disclose the anticystitis glandularis effects of vitamin C. BioFactors (Oxford, England). 2019 Nov:45(6):912-919. doi: 10.1002/biof.1558. Epub 2019 Aug 30

[PubMed PMID: 31469455]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence