Continuing Education Activity

The BRASH acronym describes a syndrome involving bradycardia, renal failure, AV nodal blockade, shock, and hyperkalemia. The synergism between AV nodal blocking medications and hyperkalemia results in a life-threatening condition that requires prompt recognition and management. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of BRASH syndrome and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the pathophysiology of BRASH syndrome.

Review the risk factors for developing the BRASH syndrome.

Describe the presentation of a patient with BRASH syndrome.

Summarize the management considerations for patients with BRASH syndrome.

Introduction

The BRASH acronym is used to describe a syndrome where the synergistic effects of AV nodal blockers and renal impairment lead to severe bradycardia and hyperkalemia. It is named after the signs associated with this condition: Bradycardia, Renal Failure, AV nodal blockade, Shock, and Hyperkalemia. While this is a new acronym, the connection between these medications and renal failure has been described for years.

Since their development in the 1960s, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers are widely used to treat conditions such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation. Both classes of medications exert their effect at the AV node, resulting in a decreased heart rate. Like many pharmaceuticals, AV nodal blockers are associated with adverse reactions. The most common of these being fatigue, dizziness, sleep disturbance, and dyspnea. However, BRASH syndrome is an underrecognized complication that can result in high morbidity if not recognized and treated appropriately, leading to cardiovascular collapse and multi-system organ failure.[1]

Etiology

This syndrome is a distinct entity that is becoming more prevalent as a cause of profound bradycardia due to the compounding comorbidities of the aging population and the advent of new pharmaceuticals targeting cardiac output. The synergy between AV nodal blockade and renal failure leads to a vicious cycle of profound bradycardia and hyperkalemia. It is hypothesized that although common, it is often unrecognized and therefore misdiagnosed in the ICU.[2]

Epidemiology

As this is a newly termed condition, little is known regarding the epidemiology of this syndrome; however, case reports indicate a higher prevalence in elderly individuals with both underlying cardiac and renal impairment. The risk of developing this complication increases further when the patient is on multiple AV nodal blockers. ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers also increase the risk as these medications increase the likelihood of developing an acute kidney injury as well as hyperkalemia.[3]

Pathophysiology

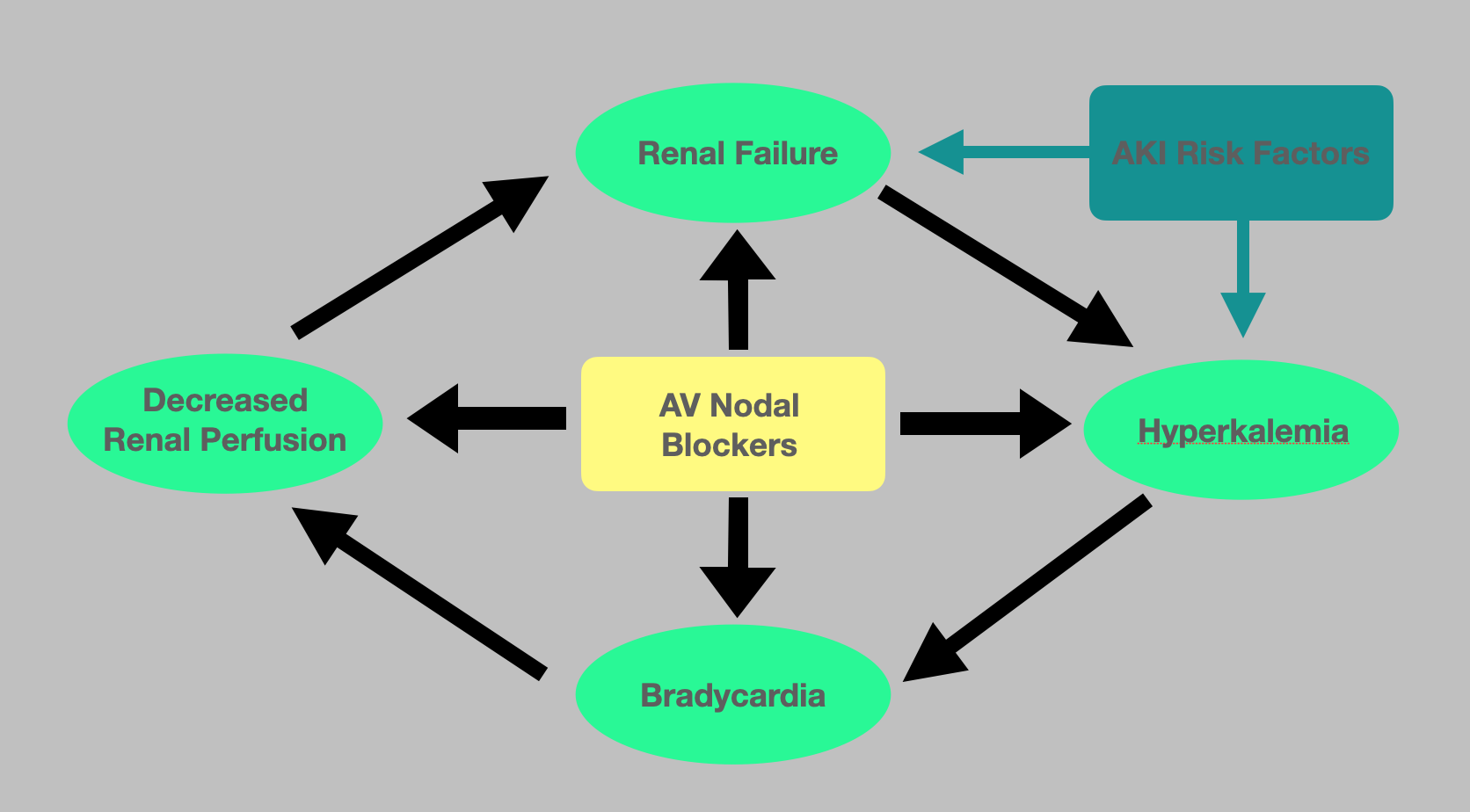

The pathophysiology underlying BRASH syndrome is not well described however involves the synergistic effect of AV nodal blockade and hyperkalemia resulting in severe bradycardia (see Figure. Pathophysiology of BRASH Syndrome). The resulting reduction in cardiac output, in turn, leads to poor renal perfusion, therefore, worsening the acute kidney injury as well as the degree of hyperkalemia. It is well documented that severe hyperkalemia alone can cause bradycardia. However, due to this synergistic effect, profound bradycardia can occur even in the setting of mild hyperkalemia. Renally cleared AV nodal blockers, such as metoprolol and amlodipine, impose a greater risk as the renal tubules' concentrations inversely increase as the GFR decreases. If undiagnosed, this can progress to multi-system organ failure requiring transvenous pacing and hemodialysis. This vicious cycle is often initiated by an innocuous event such as recent illness or medication changes. One of the most common causes is hypovolemia resulting from dehydration and a subsequent pre-renal acute kidney injury. This is often precipitated by a gastrointestinal illness such as gastroenteritis or a decreased oral intake.[4] One study found a temporal association between the development of bradyarrhythmias and hyperkalemia in the warm summer months that was due to the increased likelihood of developing dehydration. Other common triggers include up-titration of medications that alter the cardiac output or renal perfusion as well as the addition of nephrotoxic agents or potassium-sparing diuretics.[5][4]

History and Physical

Clinical presentations in these patients vary widely as they can range from asymptomatic bradycardia to cardiogenic shock requiring vasopressors and hemodialysis. Despite these variations, all patients will present with profound bradycardia. As this syndrome is often precipitated by decreased renal perfusion, history often includes recent gastrointestinal illness, dehydration, recent medication changes, or other history components identified as risk factors for acute kidney injury. It is important to note that this syndrome is not dose-dependent when considering the role that AV nodal blockers play.[6]

Evaluation

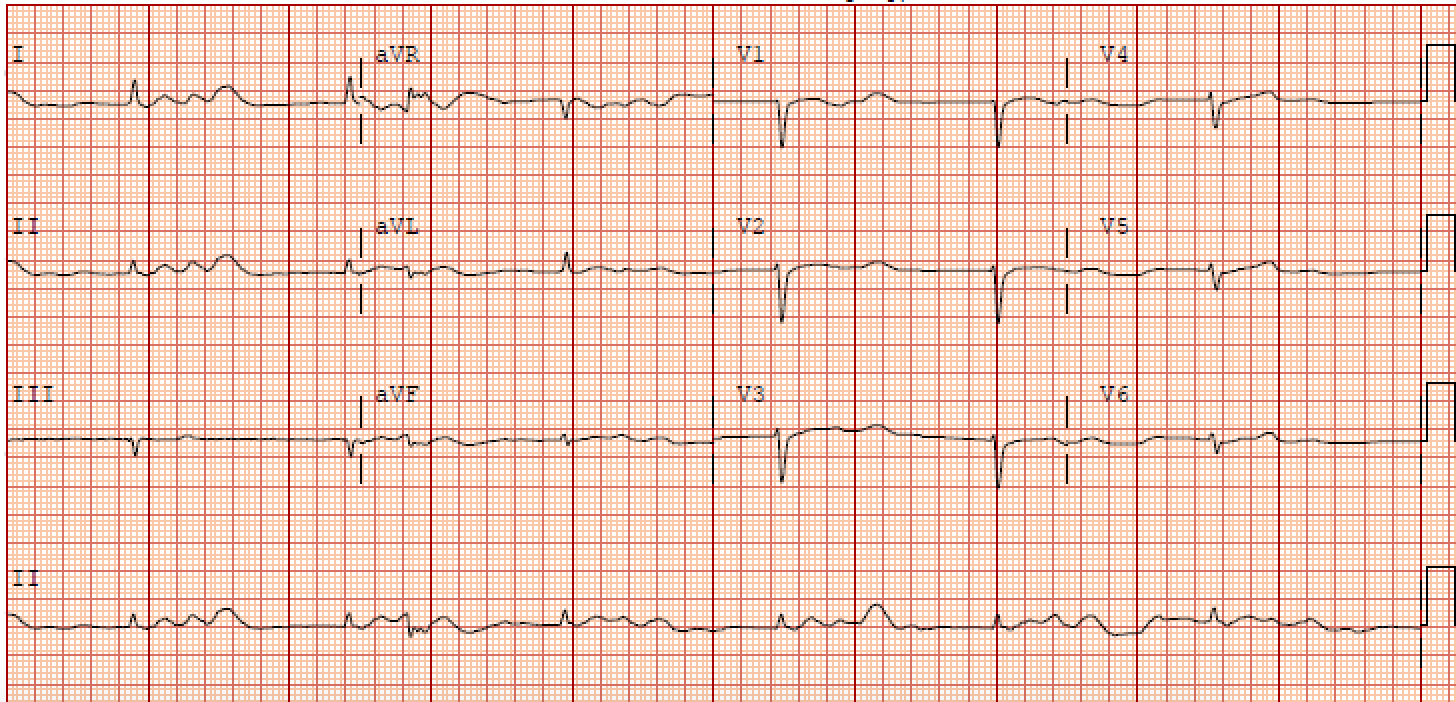

An ECG is vital in determining BRASH syndrome from other causes of bradycardia, such as isolated hyperkalemia (see Graph. Electrocardiographic Findings, BRASH Syndrome). It is, however, commonly underwhelming as it does not typically demonstrate the stereotypical electrocardiographic changes seen with hyperkalemia. In isolated hyperkalemia, as the serum potassium levels elevate, the T waves begin to peak with PR interval prolongation followed by QRS widening and subsequent bradycardia; however, these morphologies are commonly absent in BRASH syndrome patients.

A comprehensive metabolic panel will demonstrate some degree of hyperkalemia. Many case reports are documenting profound bradycardia associated with even mild hyperkalemia. One case report described a patient on Verapamil who developed BRASH syndrome with a serum potassium level of 5.1 mEq/L; however, potassium levels from 5.5-7.0 mEq/L are more commonly documented. Regardless of the degree of hyperkalemia, excess potassium is cardiotoxic and results in decreased membrane excitability leading to worsening bradycardia.

An acute kidney injury is also common. While the majority of these patients have a tenuous renal function at baseline, there will be an obvious decline in GFR as well as an increase in BUN and creatinine. The kidney injury often results in uremic acidosis. The remaining laboratory studies will vary depending on the patient’s presentation. However, any other laboratory abnormalities noted may help identify the inciting event that leads to this syndrome, which will, in turn, aid in management.[7]

Treatment / Management

Due to the multiple components of this syndrome, physicians often focus on the "dominant feature" instead of the entire syndrome when planning resuscitative efforts. It is important to note that this is a syndrome, therefore describing a constellation of symptoms, not an underlying cause. Both bradycardia and hyperkalemia can be life-threatening and require immediate intervention. While most improve with supportive therapy, the standard approach to hyperkalemia treatment should be used.

Hypocalcemia increases the cardiotoxic effects of hyperkalemia; therefore, prompt intravenous administration of either calcium chloride or calcium gluconate is warranted. Calcium chloride contains three times the amount of calcium when compared to calcium gluconate. However, calcium gluconate is universally used due to patient tolerance when administered peripherally. The standard dose of calcium gluconate is 10 mL of 10% solution or 1 gram IV, given over 5-10 minutes. The standard dose of calcium chloride is also 1 gram IV given over 1 to 2 minutes.[8]

If calcium fails to improve the bradycardia within five minutes, it can be readministered. If bradycardia persists, epinephrine can be used, which will increase the heart rate and increase the systemic vascular resistance and shift potassium back into the cells. This can be accomplished with a push dose pressor of 10 to 20 mcg of a 1 to 100,000 dilution. It is important to note that the standard ACLS approach to bradyarrhythmias, which involves the use of atropine, may not work as this bradycardia is not vagally-mediated.

Combination therapies that promote the intracellular shift of potassium or increase total body clearance further improve response. Insulin acts to reduce serum potassium levels by shifting potassium back into the cell. Ten regular insulin units should be administered intravenously as a bolus followed by 25 to 50 grams of 50% dextrose to help prevent hypoglycemia. Some studies show that it is reasonable to hold dextrose when glucose is >250 mg/dl; however, insulin is renally cleared; therefore, withholding dextrose in the setting of an acute kidney injury may result in a prolonged hypoglycemic state. Nebulized albuterol can also be used for potassium shifting into cells. This treatment is dose-dependent, with the standard dose being 15-20 mg. Albuterol will not only shift potassium back into the cells, but the adverse effect of the beta-2 blockade resulting in tachycardia would be beneficial in this setting.[9][10][11]

After addressing and managing the apparent life-threatening aspects, the underlying cause must be addressed. History alone will likely reveal the inciting event. Bedside limited ultrasound is also vital in determining volume status since hypovolemia is the most common causative event. IV hydration will be patient-specific. Large volume resuscitation should be done with a pH-guided approach depending on the initial acid-base disorder. Balanced crystalloids are appropriate in patients presenting with an initial pH between 7.35 and 7.45. Large volume resuscitation with 0.9% normal saline has been known to cause hyperchloremic acidosis; therefore, this agent should be reserved for those presenting with metabolic alkalosis.[12]

A non-anion gap metabolic acidosis, specifically a uremic acidosis, is common in BRASH syndrome; therefore, it has been proposed that isotonic bicarbonate, 150 mEq/L sodium bicarbonate in D5W, should be the fluid of choice. The BICAR-ICU trial studied sodium bicarbonate as the resuscitative fluid of choice in 389 patients admitted to the ICU and its role in all-cause mortality. While the primary end-point suggested a decrease in mortality when using bicarbonate for resuscitation, it was not statistically significant. It did, however, show an improvement in morbidity, as it decreased the need for emergent dialysis from 52% to 35% (p=0.0009).[13]

Kaliuresis describes the process of increasing potassium excretion through the urine. This process is a definitive treatment of hyperkalemia as it effectively removes the potassium from the body. Adequate fluid resuscitation as described above is imperative for diuretic use to be successful. This is generally achieved through the use of loop diuretics, thiazides, or acetazolamide. Successful therapy often requires higher doses of the diuretic due to the underlying renal failure. Mild/moderate hyperkalemia may be successfully treated with high-dose loop diuretics alone, such as furosemide 60 to 100 mg IV or bumetanide 2 mg IV. However, more severe hyperkalemia often requires the addition of a thiazide diuretic. Combination therapy has been shown to improve diuresis in those resistant to high-dose loop diuretics. Intravascular volume loss through diuresis should be replenished to maintain isovolemic kaliuresis. In the setting of anuria, emergent dialysis is warranted for the definitive removal of potassium.[14][15]

In persistent hypotension not responsive to IV fluids, vasopressors should be initiated to improve organ perfusion. Few studies have suggested the initiation of an epinephrine infusion or isoproterenol would be appropriate.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

BRASH syndrome shares many clinical signs and symptoms with both AV nodal blocker toxicity secondary to overdose as well as hyperkalemia alone. These are important to keep on the differential as definitive management will vary. Clinical history provides clues that will help differentiate these two from BRASH syndrome. As noted above, these patients are often taking their medications as prescribed. Fingerstick glucose can help differentiate BRASH syndrome from overdose since beta-blocker toxicity often results in hypoglycemia, while hyperglycemia is common with calcium channel blocker toxicity. Potassium derangements are also not typically noted in the overdose setting.[17][18]

It is well known that hyperkalemia can independently cause bradycardia. However, this is not typically seen unless the potassium levels exceed 7 mEq/L. EKG changes associated with potassium levels of 5.5 to 6.5 mEq/L include peaked T waves, while moderate hyperkalemia (6.5 to 7.0 mEq/L) is associated with a flattening of P waves and PR prolongation. It is not until serum potassium levels reach >7.0 mEq/L that there are QRS widening and bradycardia. This progression of EKG findings is common in hyperkalemia-induced bradycardia however are often absent in BRASH syndrome.[19]

Prognosis

Most cases of mild BRASH syndrome respond well to basic medical interventions, but more invasive therapies such as hemodialysis or transvenous pacing may be required. Prompt recognition of this syndrome improves prognosis and decreases the likelihood of requiring these more invasive measures. The severity of acute kidney injury and hyperkalemia are the main compounding factors that affect prognosis.

Complications

Complications of this syndrome can range from renal failure resulting in the initiation of hemodialysis to the development of cardiogenic shock requiring vasopressor initiation or transvenous pacing. If left untreated, worsening hyperkalemia will result in cardiac arrest.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education should revolve around warning signs for arrhythmia, including lightheadedness, syncope, or signs suggestive of acute renal failure, such as fluid overload or decreased urine output. AV nodal blockers are commonly prescribed for a variety of conditions; therefore, patients should be educated on this syndrome as a potential adverse reaction.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

AV nodal blockers are some of the most commonly prescribed medications; therefore, the development of this adverse reaction must be acknowledged by all healthcare providers on the interprofessional healthcare team. Recognizing that the aging population that is often seen in the Emergency Department is at higher risk of renal failure and medication side effects is extremely important as it leads to clinicians having a higher index of suspicion for uncommon syndromes such as BRASH syndrome. In most cases, the nursing staff will administer the drugs in clinical and inpatient settings, and they must be aware of these limitations and alert the team if they deem anything to be potentially hazardous. Outpatient pharmacists have an important role in reviewing patients' outpatient medications and new prescriptions, avoiding duplicate therapy, and alerting patients to risks of polypharmacy. Early identification and diagnosis by the healthcare team members lead to the development of appropriate management plans that, in turn, affect outcomes.