[1]

Van Laecke S. Hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia. Acta clinica Belgica. 2019 Feb:74(1):41-47. doi: 10.1080/17843286.2018.1516173. Epub 2018 Sep 17

[PubMed PMID: 30220246]

[2]

Wilders R, Verkerk AO. Long QT Syndrome and Sinus Bradycardia-A Mini Review. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2018:5():106. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00106. Epub 2018 Aug 3

[PubMed PMID: 30123799]

[3]

Khan Q, Ismail M, Haider I. High prevalence of the risk factors for QT interval prolongation and associated drug-drug interactions in coronary care units. Postgraduate medicine. 2018 Nov:130(8):660-665. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2018.1516106. Epub 2018 Sep 5

[PubMed PMID: 30145917]

[4]

De Vecchis R, Ariano C, Di Biase G, Noutsias M. Acquired drug-induced long QTc: new insights coming from a retrospective study. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 2018 Dec:74(12):1645-1651. doi: 10.1007/s00228-018-2537-y. Epub 2018 Aug 15

[PubMed PMID: 30112668]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[5]

Salem JE, Dureau P, Bachelot A, Germain M, Voiriot P, Lebourgeois B, Trégouët DA, Hulot JS, Funck-Brentano C. Association of Oral Contraceptives With Drug-Induced QT Interval Prolongation in Healthy Nonmenopausal Women. JAMA cardiology. 2018 Sep 1:3(9):877-882. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.2251. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30073300]

[6]

Salem M, Reichlin T, Fasel D, Leuppi-Taegtmeyer A. Torsade de pointes and systemic azole antifungal agents: Analysis of global spontaneous safety reports. Global cardiology science & practice. 2017 Jun 30:2017(2):11. doi: 10.21542/gcsp.2017.11. Epub 2017 Jun 30

[PubMed PMID: 29644223]

[7]

Porta-Sánchez A, Gilbert C, Spears D, Amir E, Chan J, Nanthakumar K, Thavendiranathan P. Incidence, Diagnosis, and Management of QT Prolongation Induced by Cancer Therapies: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017 Dec 7:6(12):. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007724. Epub 2017 Dec 7

[PubMed PMID: 29217664]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[8]

Heemskerk CPM, Pereboom M, van Stralen K, Berger FA, van den Bemt PMLA, Kuijper AFM, van der Hoeven RTM, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Becker ML. Risk factors for QTc interval prolongation. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 2018 Feb:74(2):183-191. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2381-5. Epub 2017 Nov 22

[PubMed PMID: 29167918]

[9]

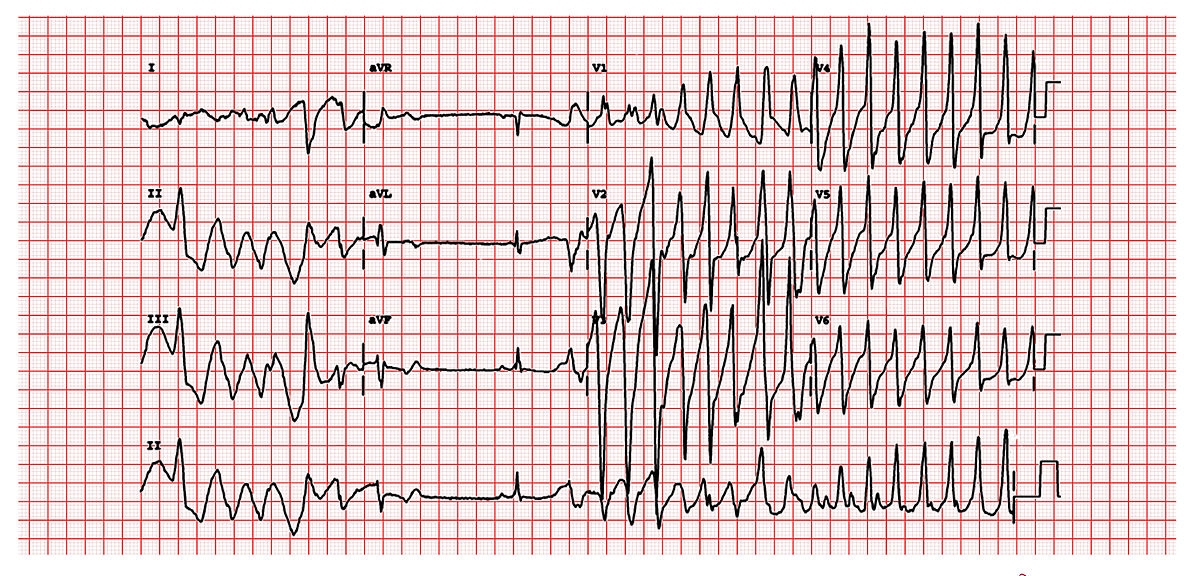

Baldzizhar A, Manuylova E, Marchenko R, Kryvalap Y, Carey MG. Ventricular Tachycardias: Characteristics and Management. Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 2016 Sep:28(3):317-29. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2016.04.004. Epub 2016 Jun 22

[PubMed PMID: 27484660]

[10]

Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, Alders M, Bikker H, Christiaans I. Long QT Syndrome. GeneReviews(®). 1993:():

[PubMed PMID: 20301308]

[11]

Turner JR, Rodriguez I, Mantovani E, Gintant G, Kowey PR, Klotzbaugh RJ, Prasad K, Sager PT, Stockbridge N, Strnadova C, Cardiac Safety Research Consortium. Drug-induced Proarrhythmia and Torsade de Pointes: A Primer for Students and Practitioners of Medicine and Pharmacy. Journal of clinical pharmacology. 2018 Aug:58(8):997-1012. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1129. Epub 2018 Apr 19

[PubMed PMID: 29672845]

[12]

de Lemos ML, Kung C, Kletas V, Badry N, Kang I. Approach to initiating QT-prolonging oncology drugs in the ambulatory setting. Journal of oncology pharmacy practice : official publication of the International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners. 2019 Jan:25(1):198-204. doi: 10.1177/1078155217748735. Epub 2018 Jan 3

[PubMed PMID: 29298624]

[13]

Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, Deal BJ, Dickfeld T, Field ME, Fonarow GC, Gillis AM, Granger CB, Hammill SC, Hlatky MA, Joglar JA, Kay GN, Matlock DD, Myerburg RJ, Page RL. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Executive summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart rhythm. 2018 Oct:15(10):e190-e252. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.10.035. Epub 2017 Oct 30

[PubMed PMID: 29097320]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[14]

Crimmins S, Vashit S, Doyle L, Harman C, Turan O, Turan S. A multidisciplinary approach to prenatal treatment of congenital long QT syndrome. Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU. 2017 Mar 4:45(3):168-170. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22386. Epub 2016 Aug 5

[PubMed PMID: 27492745]

[15]

Shulman M, Miller A, Misher J, Tentler A. Managing cardiovascular disease risk in patients treated with antipsychotics: a multidisciplinary approach. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2014:7():489-501. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S49817. Epub 2014 Oct 31

[PubMed PMID: 25382979]

[16]

van Aerde KJ, Kalverdijk LJ, Reimer AG, Widdershoven JA. [QT interval prolongation and psychotropic drugs in children and adolescents: proposed guideline]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. 2008 Aug 9:152(32):1765-70

[PubMed PMID: 18754307]

[17]

Tse G,Gong M,Meng L,Wong CW,Bazoukis G,Chan MTV,Wong MCS,Letsas KP,Baranchuk A,Yan GX,Liu T,Wu WKK, Predictive Value of T {sub}{b}peak{/b}{/sub} - T {sub}{b}end{/b}{/sub} Indices for Adverse Outcomes in Acquired QT Prolongation: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in physiology. 2018

[PubMed PMID: 30233403]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[18]

Ramalho D, Freitas J. Drug-induced life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death: A clinical perspective of long QT, short QT and Brugada syndromes. Revista portuguesa de cardiologia. 2018 May:37(5):435-446. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2017.07.010. Epub 2018 Apr 7

[PubMed PMID: 29636202]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence