Continuing Education Activity

Asystole, colloquially referred to as flatline, represents the cessation of electrical and mechanical activity of the heart. Asystole typically occurs as a deterioration of the initial non-perfusing ventricular rhythms: ventricular fibrillation (V-fib) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (V-tach). This activity describes the causes, presentation, and pathophysiology of asystole and stresses the importance of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of asystole.

Outline the presentation of a patient in asystole.

Explain the management options available for asystole.

Summarize the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by asystole.

Introduction

Asystole, colloquially referred to as flatline, represents the cessation of electrical and mechanical activity of the heart. Asystole typically occurs as a deterioration of the initial non-perfusing ventricular rhythms: ventricular fibrillation (V-fib) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (V-tach). Additionally, pulseless electrical activity (PEA) can cease and become asystole. Victims of sudden cardiac arrest who present with asystole as the initial rhythm have an extremely poor prognosis (10% survive to admission, 0 to 2% survival-to-hospital discharge rate).[1][2][3] Asystole represents the terminal rhythm of a cardiac arrest.

In out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, prolonged resuscitation efforts in a patient who presents in asystole are unlikely to provide a medical benefit. Termination of resuscitation efforts should be considered in these patients, in consultation with online medical direction, as allowed by local protocols. The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians (NAEMSP) both recommend emergency medical services systems and have written protocols that allow for termination of resuscitation efforts by emergency medical services providers for a select group of patients in which further resuscitative measures and transport to the local emergency department would be considered futile.[4]

Etiology

The causes of asystole in cardiac arrest are wide and varied. Asystole typically results from decompensation of prolonged ventricular fibrillation arrest. Additionally, attempted defibrillation of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation can precipitate asystole. However, any cause of cardiac arrest can eventually result in asystole if not promptly treated. When evaluating a patient with an initial cardiac rhythm of asystole, the reversible causes must be considered. A useful mnemonic taught in Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) for the reversible causes of cardiac arrest involves the Hs and Ts. The Hs include Hypovolemia, Hypoxia, Hydrogen ion (acidosis), Hypo/Hyperkalemia, and Hypothermia. The Ts include Tension pneumothorax, Tamponade (cardiac), Toxins, and Thrombosis (both pulmonary and coronary). When identified, these cases should be immediately treated.[5][6]

Epidemiology

Each year, approximately 300,000 to 400,000 Americans experience a cardiac arrest outside of the hospital, with the mortality of these cases being extremely high. Data vary in different regions of the country and various studies. Differences range from 4.6% to 11% survival-to-hospital discharge rate.[2][3][7] An extensive surveillance study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 2005 through 2010 evaluated 40,274 out-of-hospital cardiac arrest cases entered into the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) system. A total of 31,645 cases had a documented presenting initial rhythm. This is the largest number of cases (45.1%) presented in asystole. However, asystole had the lowest survival rate (2.3%).[8]

Fewer data are available with in-hospital cardiac arrest. This, in addition to a lack of reporting consistency, makes the true number of in-hospital cardiac arrest cases largely unknown. Extrapolation of one large data set estimates approximately 200,000 in-hospital adult cardiac arrest cases per year. This estimate was confirmed in a second study using the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation registry. Neither of these studies investigated cardiac rhythms associated with cardiac arrest.[1][9]

Pathophysiology

Asystole results from failure of the heart’s intrinsic electrical system or an extracardiac cause. Extracardiac causes are varied. They include the Hs and Ts discussed above and their causes. Asystole typically occurs as a deterioration of the non-perfusing ventricular rhythms. If not rapidly corrected, electrical and mechanical cessation of cardiac activity will occur. This is manifested as asystole on the cardiac monitor.

History and Physical

The findings of cardiac arrest are straightforward. A patient who is in cardiac arrest is unresponsive to all stimuli and is without spontaneous breathing or a palpable pulse. The American Heart Association (AHA) has simplified its basic life support (BLS) cardiac arrest algorithm to encourage minimal compression interruption. The current algorithm has eliminated the “look, listen, and feel” step to check for breathing in an unresponsive patient. Instead, the rescuer should observe to see whether the patient is breathing normally. Emphasis is placed on “gasping” or agonal breathing being abnormal. If the patient is not breathing or only has agonal respirations, the rescuer should check for a carotid pulse for the unresponsive adult or the brachial pulse in the unresponsive infant for no more than 10 seconds. If a pulse is not felt or the rescuer is unsure if a pulse was felt, CPR should be initiated immediately.

Evaluation

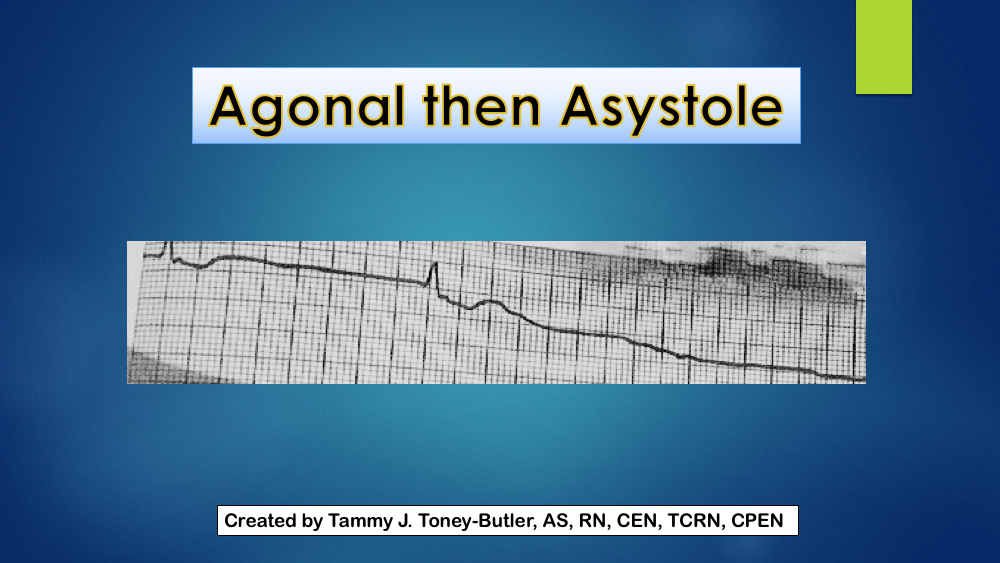

Asystole is identified on cardiac monitoring. In asystole, there is no waveform present on the cardiac monitor, only an isoelectric “flat” line. This includes a lack of P-waves, QRS complexes, and T-waves.

An arterial blood gas and potassium levels should be obtained stat. If available, an echocardiogram can be done to document the absence or presence of heart wall motion.

Treatment / Management

Asystole should be treated following the current American Heart Association BLS and ACLS guidelines. High-quality CPR is the mainstay of treatment and the most important predictor of a favorable outcome. Asystole is a non-shockable rhythm. Therefore, if asystole is noted on the cardiac monitor, no attempt at defibrillation should be made. High-quality CPR should be continued with minimal (less than five seconds) interruption. CPR should not be stopped to allow for endotracheal intubation. Epinephrine (1 mg via intravenous or intraosseous line) should be delivered every three to five minutes, and treatment of reversible causes addressed.

Vasopressin can be administered before or after epinephrine, but the benefits remain questionable.

Even though transcutaneous pacing is widely done, there is no evidence that it improves survival.

Asystole is considered a terminal rhythm of cardiac arrest. Therefore, discussion of termination of resuscitation should be considered during an in-hospital cardiac arrest in the appropriate clinical picture. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients in asystole should also be considered for the cessation of efforts according to local protocol.[4]

Patients who are resuscitated need to be monitored in the ICU. Some experts recommend inducing hypothermia on all patients who survive cardiac arrest.

Differential Diagnosis

Prognosis

The prognosis in asystole depends on the cause of the rhythm, time of intervention, and success of ACLS. Resuscitation is generally successful in cases of cardiac arrest due to choking on food or pacemaker failure. Overall the prognosis is poor, and the survival is even poorer if there is asystole after resuscitation. Data indicate that less than 2% of people with asystole survive. Recent studies do document improved outcomes, but many continue to have residual neurological deficits.

Complications

- Pneumothorax

- Air embolism

- Spleen, stomach, or colon rupture

- Hemothorax

- Liver laceration

- Fractured ribs

Pearls and Other Issues

Pitfalls

Providers should differentiate between asystole and fine ventricular fibrillation, which may respond to defibrillation.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

I am a military service member. This work was prepared as part of my official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

All healthcare workers, including the nurse practitioner, should be familiar with asystole and its management. In the hospital, it is usually the nurse who first identifies a patient in asystole and sounds the alarm.

Asystole should be treated according to current American Heart Association BLS and ACLS guidelines. One person should take charge and control the resuscitation. In all hospitals, there are specially assigned teams consisting of different professionals who attend cardiac arrests. The role of the nurse is to document and provide the necessary supplies. High-quality CPR is the mainstay of treatment and the most important predictor of favorable outcomes. Asystole is a non-shockable rhythm. Therefore, if asystole is noted on the cardiac monitor, no attempt at defibrillation should be made. In many hospitals, it is mandatory for all healthcare workers who look after patients to be certified in BLS and ACLS.

After every resuscitation, the ACLS cart should be refurbished with supplies. One member of the nursing staff should always make sure that the supplies and equipment to run a cardiac arrest are in working order and available.

The best outcomes are achieved with a coordinated interprofessional team approach. [Level 5]