Introduction

The tibialis anterior muscle, also known as the tibialis anticus, is the largest of four muscles in the anterior compartment of the leg. Its thick muscle belly arises from its proximal attachment at the lateral tibia; the tibialis anterior tendon (TAT) inserts distally on the medial border of the foot. The muscle is primarily responsible for dorsiflexion and inversion of the foot.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Anatomy

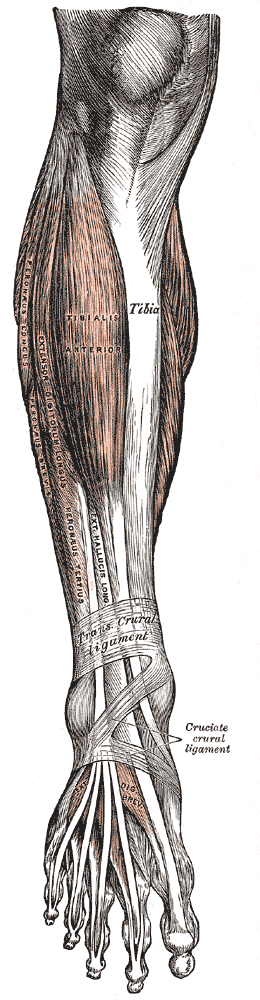

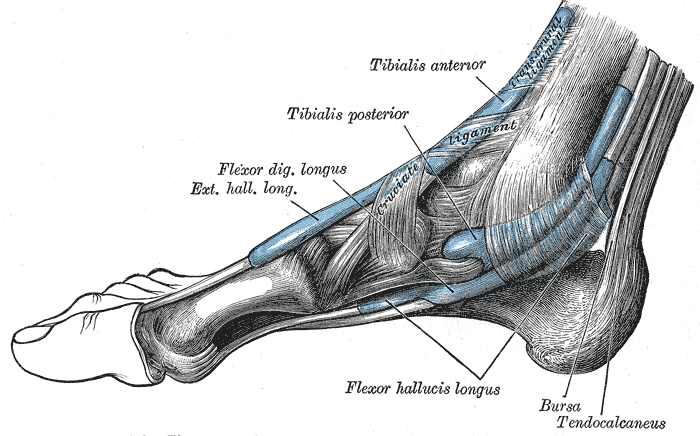

The tibialis anterior muscle, specifically its fleshy muscle belly, has a confluence of proximal attachments. These include the lateral condyle of the tibia, the proximal two-thirds of the lateral surface of the tibial shaft, the anterior surface of the interosseous membrane between the tibia and fibula, the deep surface of the fascia cruris, and the intermuscular septum between it and the extensor digitorum longus. The tibialis anterior tendon (TAT) begins at the distal one-third of the tibia. It travels across the anterior ankle and dorsum of the foot to insert vertically on the medial cuneiform and the base of the first metatarsal. It is the most medial tendon of the ankle and foot.

The extensor retinaculum (ER), a transverse aponeurotic band comprised of superior and inferior components, covers the anterior ankle and foot. In most cases, the tibialis anterior tendon passes beneath the extensor retinaculum, so the extensor retinaculum holds the TAT in place. In 25% of cases, however, the superficial and deep layers of the superior extensor retinaculum form a separate tunnel for the tibialis anterior tendon. The synovial tendon sheath of the tibialis anterior tendon extends from above the superior extensor retinaculum, inferiorly to the level of the talonavicular joint. The main synovial bursa is between the tendon, the cuneometatarsal joint, and the medial cuneiform.

Function

The tibialis anterior (TA) is the strongest dorsiflexor of the foot. Dorsiflexion is critical to gait because this movement clears the foot off the ground during the swing phase.[3]

The tibialis anterior, along with the tibialis posterior, is also a primary inverter of the foot. Because the TA arises from the lateral tibia and the tendon inserts on the medial border of the foot, muscle contraction lifts structures of the medial arch (medial cuneiform, first metatarsal, navicular, talus) into adduction-supination or inversion. The movement of inversion occurs at two synovial joints in the foot: the subtalar joint, between the talus and calcaneus, and the midtarsal joint, between the talus and navicular bone. The tibialis anterior is such a powerful inverter that muscles of the lateral compartment must be engaged in eversion for the TA to dorsiflex the foot without inversion.

Due to its insertion on the medial foot, the tibialis anterior also supports the medial longitudinal arch of the foot. The medial arch is higher than the lateral arch and is formed by the following bones: calcaneus, talus, navicular, three cuneiforms, and the first three metatarsals.[4][5]

Embryology

The tibialis anterior muscle, a lower limb muscle, arises from the myotome of the paraxial mesoderm (somites). At four gestational weeks, limb buds develop; by eight weeks, the bones and muscle groups within the limbs are well-established.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The anterior tibial artery supplies the muscle proximally. The medial tarsal arteries, which are branches of the dorsalis pedis artery, supply the tendon distally. The anterior tibial artery is 1 of 2 terminal branches at the bifurcation of the popliteal artery. The other branch is the tibioperoneal trunk, which further divides into the posterior tibial and fibular arteries.[2][6]

The anterior tibial artery passes from the posterior popliteal fossa to the anterior leg through an opening in the interosseous membrane between the tibia and fibula. It travels down the leg, supplying the anterior compartment, and into the foot, continuing as the dorsalis pedis artery. The dorsalis pedis artery then gives rise to the medial tarsal arteries at the level of the medial cuneiform, which supplies the tibialis anterior tendon distally.[2]

Nerves

The deep peroneal nerve, also called the deep fibular nerve, innervates the tibialis anterior muscle. The deep peroneal nerve is one of two terminal branches at the bifurcation of the common peroneal (fibular) nerve. The other branch is the superficial peroneal (fibular) nerve, which innervates the muscles of the lateral compartment of the leg. The common peroneal nerve itself derives from the terminating bifurcation of the sciatic nerve at the apex of the popliteal fossa; the other terminal branch is the tibial nerve. Spinal nerves L4 through S1 comprise the common peroneal nerve. This nerve wraps around the neck of the fibula and passes between the attachments of the fibularis longus before giving rise to the superficial peroneal nerve and deep peroneal nerve.[7]

The deep peroneal nerve travels with the anterior tibial artery in an inferomedial direction to innervate all four muscles in the anterior compartment of the leg. Both the nerve and the artery pass between the tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus proximally and between the tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis longus distally. The nerve then travels beneath the extensor retinaculum as it crosses the ankle joint; it terminates in the dorsum of the foot, dividing into a lateral branch and a medial branch.[8]

Muscles

The tibialis anterior is one of four muscles in the anterior compartment of the leg. The others include extensor digitorum longus (EDL), extensor hallucis longus (EHL), and fibularis tertius. The deep peroneal nerve innervates all muscles and is perfused by the anterior tibial artery. Collectively, the muscles dorsiflex and invert the foot at the ankle joint. The extensors (EDL and EHL) also extend the toes; the EDL extends the lateral four toes while the EHL extends the great toe. The fibularis tertius arises from the inferior EDL and contributes to eversion.[9]

The antagonist muscles of the anterior compartment are the muscles of the posterior compartment. Collectively, the posterior muscles plantarflex the foot at the ankle joint.

Physiologic Variants

The tibialis anterior tendon (TAT) can have varying insertion patterns. Instead of 1 tendon inserting onto the medial cuneiform and the base of the first metatarsal, the tendon can split into two bands that insert each individually. The width of these bands can be equal, or they can differ; for example, the TAT can have a wide insertion on the medial cuneiform but only a fine band of insertion at the base of the first metatarsal. It is also possible for the tendon to insert at only one of the two sites: the medial cuneiform or the base of the first metatarsal.

The muscle might also insert somewhere different altogether. For example, a deep portion of the muscle can insert more proximally into the talus. Conversely, the tendon may extend further and insert into the head of the first metatarsal or the base of the first phalanx.

Surgical Considerations

Rupture of the tibialis anterior tendon (TAT) is an uncommon pathology. However, in the event of a rupture, if the patient experiences significant loss of dorsiflexion and inversion accompanied by gait disorder, the treatment of choice is surgical repair or reconstruction. In surgery, the tendon is reattached to the bone.

Clinical Significance

Foot Drop

Because the primary function of the tibialis anterior is dorsiflexion, paralysis of this muscle results in “foot drop,” or an inability to dorsiflex, this paralysis can be caused by nerve injury, like direct damage to the deep peroneal nerve, or a muscle disorder, like ALS. “Foot drop” is often most obvious during gait when the patient cannot clear their foot during the swing phase.

Tendinitis

The tibialis anterior tendon (TAT), like any tendon, can become irritated and inflamed—a condition known as tibialis anterior tendinitis. Excessive tension on the tendon causes tendinitis, often due to repetitive, high-force activities, for example, hill running or direct contact with equipment, like a shoe that is too tight around the ankle and the tendon. Because the tendon traverses the anterior ankle and inserts on the medial foot, most patients will complain of pain at the front of the ankle or the medial midfoot. Pain will be aggravated by the stressful activity and alleviated by rest. Symptoms usually present gradually and get progressively worse.

On exam, the patient will have tenderness over the tendon and maybe even swelling. Loading the tendon, as in dorsiflexion, will exacerbate the pain. Treatment is conservative. Because the injury is due to exertion, the primary treatment is limiting activity. NSAIDs can be used for analgesia. It is also important to stretch the calf, decreasing the resistance to dorsiflexion. A stabilizing or restricting ankle brace may also decrease the load through the tendon.[10]

Tibial Stress Syndrome (Shin Splints)

The tibialis anterior muscle is often overused, resulting in a tibial stress syndrome commonly known as shin splints. Anterior tibial stress syndrome (ATSS) is acute and experienced by new runners or walkers; medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) is more chronic and occurs in athletes. The tibialis anterior muscle is more commonly involved in the former, while the tibialis posterior muscle is more commonly involved in the latter. However, the tibialis anterior can also cause MTSS. Both syndromes are caused by repetitive stress and strain on the tibia, often due to training errors or various biomechanical abnormalities. Training errors include the recent onset of increased activity, intensity, or duration (doing “too much, too fast”) or running/walking on hard or uneven surfaces. Biomechanical abnormalities include hyperpronation of the subtalar joint (eversion) and tibial torsion. Tibial stress syndrome, particularly MTSS, can progress to a stress fracture of the tibia. This is more common in females than males due to a higher incidence of diminished bone density and osteoporosis.[10]

In ATSS, the patient will present with tightness or tenderness in the anterior muscles of the leg that is aggravated by running or walking and alleviated with rest. The pain may begin as a dull ache but often progresses to sharper pain. As the injury progresses, pain may be present even at rest.

Since tibial stress syndrome results from overuse and repetitive stress, rest is the most important treatment in the acute phase. Ice and NSAIDs can provide analgesia. It is critical to modify the training routine and add stretching and strengthening exercises in the long term. Stretching helps prevent muscle fatigue and subsequent strain on the tibia where muscles attach; strengthening muscles, like the tibialis anterior, helps control movement to reduce stress on the tibia. It is also important to correct underlying biomechanical abnormalities.[11]

Anterior Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome occurs when tissue pressure within a closed, non-extensible muscle compartment exceeds the perfusion pressure. Pressure greater than 30 mm Hg (in relaxed muscles, normal tissue pressure is 10 to 12 mm Hg) compromises circulation and can lead to necrosis and/or ischemia. In acute compartment syndrome, the increased pressure is caused by bleeding or edema, usually due to fracture or trauma. In chronic compartment syndrome (CCS), the increased pressure in skeletal muscle is due to overexertion. Unlike other exertional injuries, like ATSS or MTSS, chronic compartment syndrome won’t respond to NSAIDs or physical therapy. In the leg, the anterior compartment is most frequently affected by compartment syndrome.[12]

Patients with compartment syndrome often present with ischemic pain, described as greater pain than one might expect given the clinical situation. The pain can be reproduced by passively stretching the muscles in the affected compartment. For example, in anterior compartment syndrome, plantarflexion will increase pain. In CCS, like other exertional injuries, the pain is aggravated by activity and alleviated by rest. Patients may also develop paresthesia due to nerve ischemia or paralysis of the affected muscles; however, neurological symptoms may also be due to a concurrent nerve injury. Ischemia may also lead to pallor and pulselessness, though the latter may be a sign of arterial injury instead. Finally, swelling is common and can make the leg feel firm and “wooden” upon palpation.

Early diagnosis of compartment syndrome is critical to avoiding poor outcomes, such as infection, contracture, and amputation. Diagnosis requires awareness of the syndrome and appropriate examination. Intra-compartmental pressure can also be measured to diagnose compartment syndrome. Fasciotomy is the standard treatment; the recommendation is to decompress all four compartments. Chronic compartment syndrome can be treated nonoperatively with complete cessation of all causative activities and massage therapy. In general, nonoperative treatment is unsuccessful.[13]