Introduction

Also termed left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), preload is a measure of the degree of the ventricular stretch when the heart is at the end of diastole. Preload, in addition to afterload and contractility, is one of the three main factors that directly influence stroke volume (SV), the amount of blood pumped out of the heart in one cardiac cycle.[1] Affected by changes in venous tone and circulating blood volume, changes in preload directly affect stroke volume, therefore influencing cardiac output and the overall function of the heart. A thorough understanding of preload, what affects it, and how pharmacological treatments can manipulate preload is essential to understanding overall cardiac physiology.[2] See Diagram. Cardiac Preload.

Cellular Level

On a cellular level, preload is related to the intrinsic properties of the actin and myosin filaments that make up the myocardial muscle. Preload determines the resting length of the cardiac muscle fibers at a given LVEDP. Initially, when preload increases, the starting length of the muscle fibers also increases; consequentially, the resting tension increases. However, the amount the muscle fibers shorten during contraction also increases correspondingly. As a result, the final length of the muscle fibers does not change dramatically.[2]

Mechanism

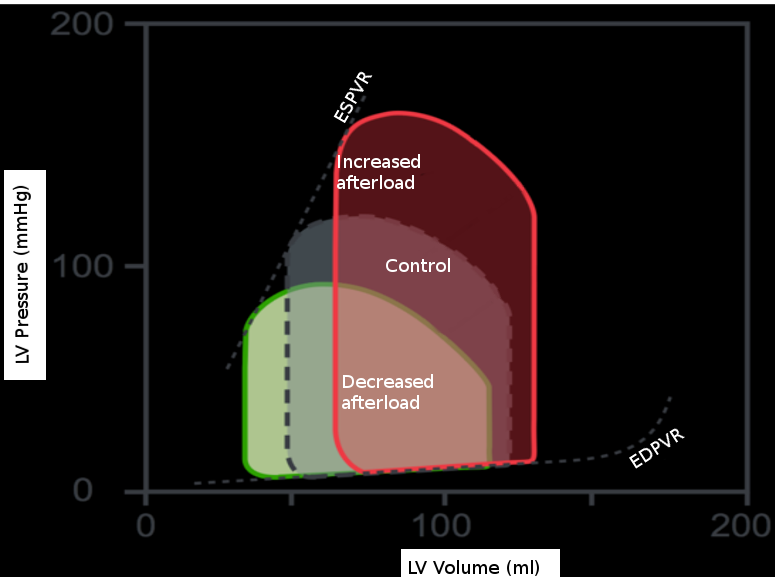

The effects of isolated changes in preload are best demonstrated on the pressure-volume (P-V) loop, which relates ventricular volume to the pressure inside the ventricle throughout the cardiac cycle. The P-V loop plots volume along the x-axis and pressure on the y-axis. The area of the loop is equal to the stroke volume, which refers to the amount of blood pumped out of the left ventricle in one cardiac cycle. This number is calculated as the end-diastolic volume (EDV), point B, minus the end-systolic volume (ESV), point A, on the graph. The effects of intramyocardial and extra myocardial events are plottable on the P-V loop. Changes in preload are visible as movements along the line showing the end-diastolic P-V relationship, as shown. If afterload and contractility are held constant, an increase in preload will result in a rightward shift along this line. As a result, the EDV increases, and thus the stroke volume increases. Also, as EDV increases, the proportion of blood ejected by the heart increases slightly; this is the ejection fraction (EF) calculated by the equation: (EDV-ESV)/EDV. The reverse is also true. A decrease in preload will result in a leftward shift down the end-diastolic P-V line, decreasing EDV, stroke volume, and a slight decrease in ejection fraction.[3]

What the P-V loop doesn’t account for are the neurohormonal and reflex responses that can affect preload. For example, the activation of beta-Adrenergic receptors leads to an increase in renin and antidiuretic hormone. Consequently, there is an increase in preload via salt and water retention. Further, stimulation of beta1-adrenergic receptors specifically, increases both the inotropy and lusitropy of the heart, which results in a shift of the end-diastolic P-V curve down and to the right, as the time the heart spends in diastole decreases. The sympathetic stimulation of the alpha-1 receptors in the veins causes vasoconstriction and forces more blood in the veins to return to the heart, increasing preload. Additionally, the release of angiotensin II stimulates the release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex; this causes additional sodium and water retention.[3]

Related Testing

One can estimate cardiac preload by measuring the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCW) using a catheter.[1] By advancing a catheter into the right or left pulmonary artery, the catheter will be fed into the smaller pulmonary artery branches and block blood flow briefly. This blockage creates a stagnant area of blood flow between the catheter tip and the pulmonary venous system, which feeds into the left atrium. Thus, the pressure recorded from the catheter in this placement estimates the pressure of the left atrium known as the PCW. In a healthy heart, since the left atrium and left ventricle share a similar pressure during diastole, as blood flows freely across the mitral valve from the LA to the LV, the PCW can also be used to estimate the LV diastolic pressure; this is a measurement of preload.[4]

Pathophysiology

As demonstrated by the pressure-volume loops, left ventricular myocardial function is determined by the combination of preload, afterload, and contractility. Thus, changes in preload are associated with a myriad of different clinical scenarios.[3]

Increases in preload, as demonstrated through an elevated PCW, are seen in several conditions such as heart failure, mitral stenosis, and mitral regurgitation. At higher preloads, the heart also has an increased oxygen demand, further debilitating the already diseased heart. In cases of heart failure, eventually, the heart cannot keep up with the increased load, and deleterious ventricular remodeling and loss of function ensue.[2]

Abnormally low preload is associated with several related pathologies, including distributive and hypovolemic shock. For example, in the beginning phases of sepsis, a hypovolemic state, induced by the capillary leak and low vascular resistance, can lead to low preload and afterload. A similar response occurs in the setting of hemorrhage. Severe blood loss leads to a decrease in circulating blood volume and consequently decreases the amount of blood returning to the heart, which accounts for the reduction in stroke work and cardiac output seen in this setting.[5]

Clinical Significance

A variety of commonly used medications affect cardiac preload. These are some of the first-line treatments for heart failure, myocardial ischemia, and hypertension. Drugs that decrease preload and the mechanism by which they work are detailed below[1][6][7][8][9]:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors – interrupts the RAAS system.

- Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) - interrupts the RAAS system.

- Nitrates – causes nitric oxide-induced vasodilation.

- Diuretics – promote the elimination of salt and water, resulting in a decreased overall intravascular volume.

- Calcium Channel Blockers – blocks calcium-induced vasoconstriction and decreases cardiac contractility.

These drugs have utility in cases such as the acute management of heart failure where the goal is to reduce the volume of blood the failing heart has to pump. By decreasing the volume overload experienced by the patient, using one or more of the above-listed medications, symptoms such as dyspnea and edema can improve rapidly. Long term, use of ACE Inhibitors or ARBs has shown to lower mortality in chronic heart failure patients by decreasing the amount of filling pressure in the heart and downregulating the compensatory neurohormonal stimulation.[6] In the treatment of myocardial ischemia, nitrates can decrease the amount of blood returning to the left ventricle, preload, by causing venous dilation. As a result, the oxygen demand of the heart decreases. This process is crucial in the treatment of ischemia.[9] A third clinical scenario in which drugs may help to reduce preload is in treating hypertension. Specifically, one of the most effective IV medications for the treatment of hypertensive emergencies is sodium nitroprusside.[7]

Additionally, several non-pathological states may result in increased preload.[3] These include:

- Pregnancy

- Exercise

- Excessive sodium intake

- IV fluid

Finally, manipulations in preload, using several bedside maneuvers, may help diagnose murmurs associated with several different conditions. For example, rapid squatting causes an increased volume in the LV at the end of diastole. This increase in preload increases the intensity of murmurs such as aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation, and ventricular septal defect. A later onset, signified by a click, will be heard in mitral valve prolapse. In contrast, maneuvers that decrease preload, such as the Valsalva maneuver or standing up, increase the intensity of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and cause an earlier onset in the click heard in mitral valve prolapse.[10]