Continuing Education Activity

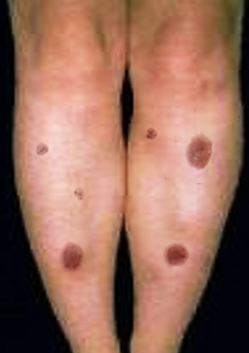

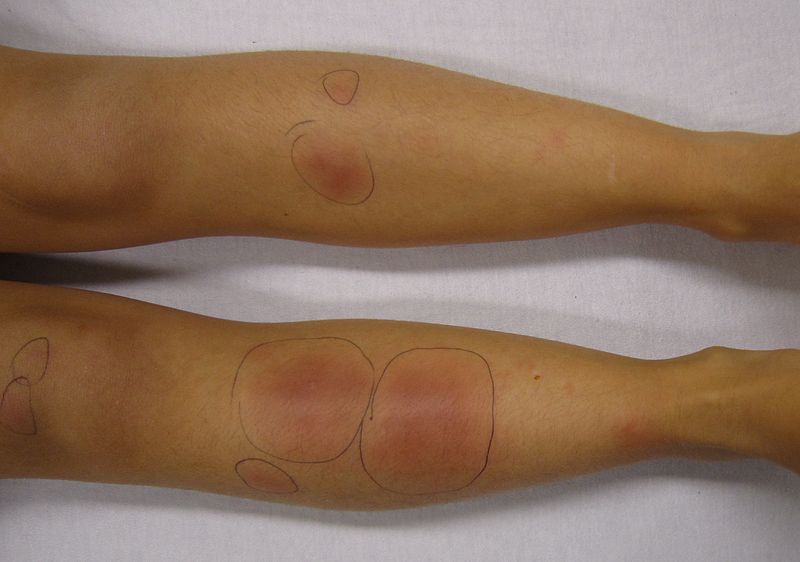

Erythema nodosum (EN) is a common acute nodular septal panniculitis, characterized by the sudden onset of erythematous, firm, solid, deep nodules or plaques that are painful on palpation and mainly localized on extensor surfaces of the legs. This activity reviews the causes, pathophysiology, and presentation of erythema nodosum and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Recall the cause of erythema nodosum.

Describe the presentation of erythema nodosum.

Summarize the treatment for erythema nodosum.

Review the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by erythema nodosum.

Introduction

Erythema nodosum (EN) is a common acute nodular septal panniculitis, characterized by the sudden onset of erythematous, firm, solid, deep nodules or plaques painful on palpation and mainly localized on extensor surfaces of the legs. These nodules are characterized by a typical histological appearance regardless of the etiology, marked by acute inflammation of the dermo-hypodermic junction and interlobular septa of the hypodermic fat, evolving without necrosis or sequelae.[1][2][3]

Erythema nodosum is an acute or recurrent hypersensitivity reaction to a variety of antigens with a clear female predominance that may be associated with several different stimuli or pathological conditions. See Images. Erythema Nodosum.

Etiology

Erythema nodosum can occur due to a vast number of underlying causes including but not limited to idiopathic, infectious, and a variety of noninfectious causes as outlined below.[4][5][6][7]

Idiopathic: No obvious etiology have been found in about 30% to 50% of published cases

Infections

Bacterial

- Streptococcal infections-most common infectious etiology commonly streptococcal pharyngitis (28 to 48%)

- Tuberculosis

- Leprosy

- Yersinia species (in Europe), salmonella, campylobacter gastroenteritis

- Mycoplasma pneumonia

- Tularemia

- Cat scratch disease (Bartonella species)

- Leptospirosis

- Brucellosis

- Psittacosis

- Chlamydia trachomatous

- Lymphogranuloma venereum

Viral

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)

- Para vaccinia

Fungal

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Blastomycosis

Parasitic

Noninfectious Causes

Drugs

- Antibiotics- penicillins, sulfonamides

- Miscellaneous drugs- Oral contraceptives, bromides, iodides, TNF-alpha inhibitor

Malignancy

- Leukemia

- Lymphoma

- Occult malignancies

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Crohn disease

- Ulcerative colitis

Miscellaneous

- Sarcoidosis-Lofgren syndrome (a triad of erythema nodosum, acute arthritis, and hilar lymphadenopathy)

- Pregnancy

- Whipple disease

- Behcet disease

Some pregnant patients may develop erythema nodosum during the second trimester. In addition, recurrence of the disorder may also occur with future pregnancies.

Epidemiology

EN is the most common clinical form of acute nodular hypodermis. It occurs more often in women between 25 and 40 years but can be observed at any age. Compared to men, women are affected three to six times more. It is rare without sex predominance in the pediatric population. Of worldwide ubiquitous distribution, there is, however, an ethnic and geographical difference in the incidences explained by the variation of triggering etiological factors. Familial cases have been reported and are usually caused by an infectious etiology.

Pathophysiology

EN is the result of a nonspecific cutaneous reaction to various antigens. The mechanism involved would be immunologically mediated. Numerous direct and indirect evidence supports the notion of type IV delayed hypersensitivity response to many antigens. It is postulated that the pathogenesis may be due to the deposition of immune complexes in the venules of subcutaneous fat, the production of oxygen free radicals, TNF-alpha, and granuloma formation. However, this hypothesis is not accepted by all authors.

Histopathology

Skin biopsy is not usually needed in the typical forms as a diagnosis can be reached from a detailed history and physical examination. Usual features suggestive of EN include acute onset tender nodules on typical locations(most commonly on shins).

Skin biopsy is useless in typical forms. It is indicated in cases of unusual topography, the persistence of nodules several weeks, fistulization or atrophic scarring, and/or livedoid disposition of nodules. It highlights the involvement of interlobular septa by a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate, sparing fat lobules and vessels. This aspect is invariable, whatever the etiology.

History and Physical

EN is characterized in a rather stereotyped way, whatever its cause, by the following evolutionary aspects:

Prodromal Phase

- Nonspecific from 3 to 6 days

- Marked by fever, joint, and sometimes abdominal pain.

- Often a picture of infection nasopharyngeal, with a slight alteration of the general condition.

Stade Phase

- Settles quickly in 1 to 2 days.

- The general syndrome occurs with fever, and arthralgia of the prodromal phase persists or increases.

- Nodules appear on the extensor surfaces of the legs and knees, and sometimes thighs and forearms.

- Nodules are small, 3 to 6, sometimes more, bilateral, roughly symmetrical, and spontaneously painful.

- The clinical examination allows specifying the characters of the knots: 10 to 40 mm diameter; warm and firm on palpation, which accentuates their painful character; mobile in relation to the deep planes.

- The pain of the lesions is exacerbated by orthostatism, which leads the patient to seek the lying position with raised legs spontaneously.

- Edema of the ankles is often present.

- Hilar adenopathy may also occur and be confused with sarcoidosis

Regressive Phase

- Evolution is spontaneous but may be accelerated by rest or treatment symptomatic.

- Each nodule evolves in ten days, taking blue and yellowish contusiform aspects towards complete disappearance without sequelae.

EN never involves necrosis, ulceration, or scarring. It often evolves in several outbreaks, favored by orthostatism and spreading out, at worst, over 4 to 8 weeks. The succession of outbreaks confers on the eruption of a polymorphic appearance with knots of different ages, featuring the various shades of local biligenia.

Besides the skin lesion, more than 50% of patients will also complain of joint and muscle pain. Sometimes joint swelling and morning stiffness may be present. The swelling may resolve in a few days, but the pain may last for a few months. There is usually no joint destruction, and the synovial fluid is sterile.

Evaluation

The positive diagnosis of EN is primarily clinical. However, a thorough anamnesis (looking for tuberculous contagion, fever, bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, respiratory problems, dysphagia, etc.) should be conducted as well as a complete clinical examination, always looking for associated signs.

In typical cases, a complementary investigation for positive diagnosis is not necessary. Nevertheless, it finds its place in the etiological diagnosis. Taking into account the above, the etiological assessment of an EN should include examinations according to the clinical orientation.

- Blood count, vital signs, and C-reactive protein (in case of infectious context)

- Mantoux + chest x-ray + interferon-gamma blood test (in case of tuberculous contagion or suspicion of Löfgren syndrome)

- Throat smear + culture + rapid test - serology: anti-streptolysin O and streptodornase (in case of streptococcal suspicion)

- Viral serology, two samples at four-week intervals (in case of suspicion of virosis)

- Stool and stool examination (in case of diarrhea or digestive symptoms)

- Cutaneous biopsy in atypical cases or in case of doubt

Treatment / Management

Extended rest is desirable and may require work stoppage. Analgesics are prescribed on request. Venous compression reduces the pain felt in orthostatism. Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine (1 to 2 mg/day), may be prescribed until symptoms improve. Etiologic treatment is essential in some cases, and antibiotic therapy is needed in case of streptococcal infection or anti-tuberculosis treatment. In the case of Löfgren syndrome, pulmonary radiographic monitoring is recommended because if mediastinal adenopathies disappear in a few months in most patients, sarcoidosis may persist in 10% of cases.[8][9]

Differential Diagnosis

- Non-suppurative infectious dermo hypodermitis diagnosis

- Nodular hypodermitis with vascular involvement (periarteritis nodosa and superficial thrombophlebitis) and damage to deep vessels of medium to sometimes large diameter is associated with hypodermic septal or lobular involvement. Nodules can become necrotic. The diagnosis is primarily histological.

- Lobular hypodermitis or panniculitis involves lesions that are primarily greasy. The diagnosis is primarily histological, hence the absolute need for biopsy. Several entities have been distinguished. The nodules can liquefy, fistulate, and leave a scar.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with EN is good but there is a small risk of recurrence. The skin lesions often take months to resolve but there is usually no scarring or pigmentation change.

Pearls and Other Issues

EN is a benign syndrome with a spontaneously favorable course, which is related to an underlying condition that needs to be diagnosed by clinical examination and some complementary oriented tests. In addition to symptomatic treatment, that of the underlying condition may be necessary.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

EN is often encountered by primary care providers and nurse practitioners. While the diagnosis is clinical in most cases, sometimes a biopsy may be required to rule out another disorder. Healthcare workers should seek a consult with a dermatologist or rheumatologist if there is any doubt about the diagnosis. For the most part, the treatment is conservative with rest. Primary care clinicians should not initiate any type of medical therapy if the diagnosis is uncertain. In addition, since the diagnosis is clinical, the patient should not be subjected to unnecessary procedures. The type of laboratory workup depends on the suspected cause. While EN may be painful, it is a benign disorder that usually remits spontaneously. If the primary disorder is not managed, EN may persist for months or even years. The pharmacist should ensure that the patient is on no medication that causes EN. If the female is on an oral contraceptive, then an alternative form of contraception should be recommended. The primary care clinicians should communicate with the dermatologist to ensure that the patient is receiving the optimal level of care. [Level 5]