Continuing Education Activity

Fusiform incision is commonly used to remove lesions that are roughly round or oval. Fusiform incisions involve the surgical removal of tissue in a manner that results in the tapering of both ends of the specimen. The technique begins by determining the margins needed around a given lesion, and those margins are marked, forming a circle or an oval. The fusiform incision will include the tissue within the marked boundaries as well as additional tissue at either end to allow for the desired tapering. Removal of tissue in this manner allows the wound to be closed in a linear, side-to-side fashion with minimal surface irregularity. This activity describes the indications and technique involved in fusiform incisions and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients undergoing this procedure.

Objectives:

- Identify the anatomical structures relevant to fusiform incisions.

- Describe the equipment required to perform a fusiform incision.

- Describe the potential complications of fusiform incisions.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for optimizing care coordination and communication to advance the performance of fusiform incision and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Fusiform incision involves cutting out tissue in a manner that results in both ends of the specimen being tapered or made spindle-shaped. Removal of tissue in this manner allows the wound to be closed in a linear, side-to-side fashion with minimal surface irregularity.

Anatomy and Physiology

This incisional technique may be used on the skin in virtually any anatomic location, but size and depth of the defects are limited by proximity to vital structures and free margins. For example, large fusiform excisions are not generally practical near the eye and should not cross the free margin of the eyelid. In addition, closure of these defects causes some degree of tension. Therefore, the direction of closure should be chosen in a way that will minimize the tension on free margins or vital structures that would result in cosmetic or functional abnormalities.

Indications

Fusiform incision may be used to excise an entire lesion, or it can be used to remove just a portion of involved tissue. The tapered ends of the resulting defect allow primary closure of the wound while minimizing "standing cone deformities" or "dog ears" at the ends of the incision. Modifications of this technique may be implemented to avoid cross free margins such as the eyelid or vermilion border of the lip.

Contraindications

Caution should be exercised in patients on anticoagulant therapy, with bleeding disorders, or those with active skin infections. Consultation with the appropriate physician may be indicated in situations of uncertainty.

Equipment

Essential equipment is minimal and includes the following:

Preoperatively

- Local anesthetic (typically lidocaine 0.5% with epinephrine 1:200,000 and buffered with sodium bicarbonate)

- 3 cc syringe(s)

- 30 gauge needle(s)

- Antiseptic scrub

Intraoperatively

- Sterile drape

- Scalpel with #15 blade

- Toothed forceps

- Suture scissors

- Needle holders

- Normal saline

- Sterile gauze

- Absorbable suture (for subcutaneous/deep stitches)

- Cutaneous suture (non-absorbable or absorbable)

- Ideally, an electrosurgical device should be available for hemostasis

Postoperatively

- Nonstick dressing

- Sterile ointment (author prefers sterile petrolatum to antibiotic ointment as significant numbers of patients develop allergies to bacitracin and neomycin, while their ability to decrease infection is minimal)

- Gauze or other material to use in bulky pressure dressing

- Adhesive dressing, preferably hypoallergenic and stretchy

Personnel

While fusiform incisional surgery can be performed alone, it is very helpful to have a surgical assistant to help with controlling bleeding, cutting sutures, and applying a dressing.

Preparation

The surgical site should be examined with the patient in a neutral or natural position, usually sitting erect. The long axis of the incision is generally chosen to run parallel to the relaxed tension lines. The skin is scrubbed with alcohol, and the planned incision is drawn with a surgical marker. The patient is then placed in a position that is comfortable but allows the surgeon optimal access.

Technique or Treatment

The tissue is then injected with local anesthetic. For best aesthetic results, the long axis of the defect is usually oriented parallel to relaxed skin tension lines. While stretching and stabilizing the skin with both hands, the surgeon begins the incision at one end, being sure to start at the desired tissue depth and maintain that depth throughout the incision, including at the other end. Often the tip of the scalpel blade is used to puncture the skin at the tip of the planned incision, and then the curved belly of the blade is used to proceed with the remainder of the incision. The scalpel cutting surface should be maintained perpendicular to the skin surface plane as well, to avoid slanted sides to the defect that would result in an inverted scar after suturing. The undersurface of the specimen is then sharply dissected with the scalpel or with scissors, again maintaining the same plane throughout.[1] If the plane of the defect appears uneven after removal of tissue, additional tissue may be taken to correct this and obtain an even plane.

Once the specimen has been removed, the wound is prepared for closure. After obtaining hemostasis with electrocoagulation, most wounds will be closed in a layered fashion, starting with one or more layers of an absorbable suture in the subcutaneous fat and dermis. If necessary, the surrounding skin may be undermined to allow placement of buried vertical mattress sutures and to provide a degree of tissue mobility. In many instances, little or no undermining is required to obtain optimal closure. Excessive undermining only provides more potential space for hematoma or seroma formation. Deep sutures provide the strength of the closure, and then superficial sutures keep the skin edges flush during initial healing.[2] Superficial sutures may be absorbable or non-absorbable, and in some cases with little tension or movement, tissue glue can be used. In very small or narrow incisions with little tension, one may use only superficial sutures.

A sterile pressure dressing is placed over the incision for 1-2 days to minimize the risk of bleeding. Sterile petrolatum is applied to the incision site, and is preferable to antibiotic ointments containing neomycin or bacitracin. Those antibiotic ointments have not been shown to decrease the incidence of post-operative infection, but they do pose a significant risk of causing an allergic contact dermatitis. Fluffed gauze, cotton balls or similar material form the bulk of the dressing that will apply pressure under the adhesive tape. Strips of stretchable bandage material are ideal for placement of these dressings, and the strips should run perpendicular to the incision line so that they help pull skin edges together and take tension off the sutures.

With the adequate placement of buried sutures, superficial sutures on the face can be removed in one week, and often sooner. On the trunk and extremities, it is generally safer to allow 10-14 days, depending on the tension on the wound and the patient's level of activity. If using absorbable sutures for the superficial closure, one should choose suture material that will remain in place for an adequate period of time.

Complications

As with other forms of incisional surgery, the main risks include bleeding, scar formation, and infection. Other risks include damage to underlying structures such as nerves, aesthetic disfigurement, and functional impairment. Careful preparation and attention to detail minimize these risks.

Clinical Significance

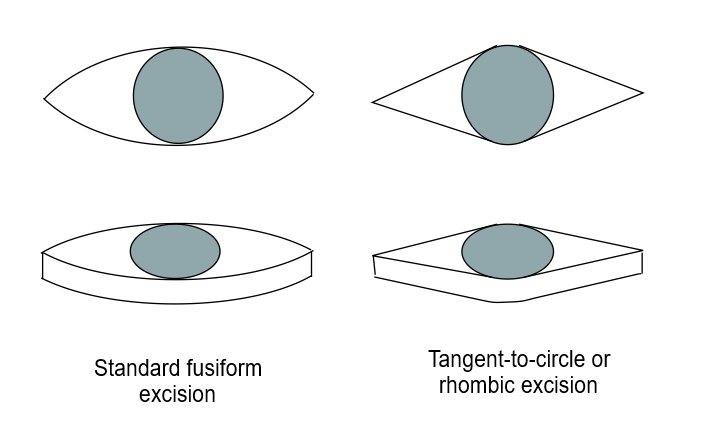

Fusiform incision is commonly used to remove lesions that are roughly round or oval. The technique begins by determining the necessary margins around a given lesion, and those margins are drawn with a marker, forming a circle or an oval. The fusiform incision will include the tissue within the marked boundaries as well as additional tissue at either end to allow for the desired tapering. Fusiform incision may be performed in several variations, but two forms are most typical. The most common form portrayed in textbooks has two sides that are rounded from end to end of the incision. A more efficient method employs straight sides on the ends of the incision, resembling a rhomboid shape.[3][4][3] In this variation, the only curved component of the defect is in the middle and corresponds to the margins around the lesion. Straight lines are drawn to meet at the rounded portion of the defect and the ends. The straight sides provide a more narrow, or acute, angle at the ends of the incision, and thus less redundant tissue is present to form a "dog ear," or standing cone, of protuberant tissue. A more narrow defect angle is less prone to tissue redundancy, but these more acute angles require a greater overall length of the defect. A 30-degree angle is suitable in most circumstances. As a general rule of thumb, a 3:1 length to width ratio often provides an approximately 30-degree defect angle without taking an excessive amount of tissue, although this may vary depending on the characteristics of the tissue and the topography in a given location.[5]

In some instances, the fusiform incision may be used to obtain a cross-section of a larger area of tissue, particularly when one wants to see histologically the transition from normal to abnormal skin or to see the architecture of a large skin neoplasm. For example, it can be used at the periphery of a keratoacanthoma to provide a large cross-section for pathologists to examine the architecture that helps to differentiate this from a more aggressive squamous cell carcinoma. In these circumstances, a longer and more narrow specimen may be harvested, allowing maximal cross-sectional tissue for examination with little tension in defect closure. Likewise, a full cross-section may be obtained in a large pigmented lesion, providing the pathologist substantial tissue for examination without creating a large defect.[6]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A few tips can optimize the successful performance and clinical and aesthetic results of an elliptical excision:

- To incise straight lines running tangential the circular or oval lesion and required margins, rather than rounding all lines. This will result in more acute angles at the ends of the wound, with less chance of standing cones.

- When performing the incision, rest both hands on the patient and stretch the skin in three directions, using the hand holding the scalpel as one "point" and using two fingers on the other hand as the other two points.

- Start the incision with the tip of the blade at the end of the defect, then use the rounded belly of the blade for the remainder of the excision. Try to maintain an even plane of cutting, using as few passes of the blade as possible.

- Use only as much undermining as necessary. Often, no undermining is needed at all, or just enough to allow proper placement of buried vertical mattress stitches. More undermining creates more "dead space" in which hematomas may collect.[7]

- When bandaging linear incisions, make sure to run tape strips perpendicular to the incision line, thus minimizing tension across the incision line.