Continuing Education Activity

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is an isolated chronic, usually bilateral, vasculopathy of undetermined etiology characterized by progressive narrowing of the terminal intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery and circle of Willis. Moyamoya syndrome (MMS) corresponds to the same moyamoya phenomenon but occurring in the background of either neurological or extra-neurological conditions, either inherited or acquired. A fragile network of abundant collateral vessels as a reaction to chronic brain ischemia develops predominantly at the base of the brain known as moyamoya vessels. This activity describes the pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of moyamoya disease and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of affected patients.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of moyamoya disease.

- Describe the presentation of a patient with moyamoya disease.

- Summarize the management options for moyamoya disease.

- Review the importance of enhanced coordination amongst interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by moyamoya disease.

Introduction

The Moyamoya disease (MMD) was first described in Japanese literature in 1957. Suzuki and Takaku first named it as “moyamoya disease” in 1969. MMD is an isolated chronic, usually bilateral, vasculopathy of undetermined etiology characterized by progressive narrowing of the terminal intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) and circle of Willis. Moyamoya syndrome (MMS) corresponds to the same moyamoya phenomenon, but in the background of either neurological or extra-neurological, whether inherited or acquired conditions. A fragile network of abundant collateral vessels as a reaction to chronic brain ischemia develops predominantly at the base of the brain known as moyamoya vessels- meaning “something hazy like a puff of smoke drifting in the air” in Japanese [1].

Etiology

Inherited conditions and/or association:

- Sickle Cell Disease or trait

- Down Syndrome (Association)

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (Association)

Acquired conditions:

- Head and/or neck irradiation

- Chronic meningitis

- Skull base tumor

- Atherosclerosis of skull base arteries

- Arteriosclerosis

- Cerebral vasculitis [1]

Epidemiology

Age of onset of the symptomatic disease has two peak distributions: 5 to 9 years of age and 45 to 49 years of age. It is most commonly seen in East Asian countries (mainly Japan and Korea) but western countries have also noted an increase in the incidence of MMD. One study done in California and Washington state involving 298 patients reported an incidence of MMD of 0.086/100,000. Recently, a study done in East Asian countries found the family history of MMD in 10%-15% of patients from the data of 2000-2011. They also noted a higher incidence of MMD among females with a female-to-male ratio of 2.2. A more recent study based on the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database reported that MMD appears to be distributed among the races according to their relative proportions in the USA population [Higher prevalence was noted among Caucasians followed by Asian Americans and the most common reason for admission was an ischemic stroke. MMD has a bimodal age distribution with the first peak in the first decade and the second peak in the fourth decade of life [1].

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of MMD remains unclear, though genetic predisposition is theorized in East Asian countries. Mutations in BRCC3/MTCP1 and GUCY1A3 genes are implicated in Moyamoya syndrome. Affected individuals are found to have concentric and eccentric fibro cellular thickening of intima within the intracranial portion of ICA. In a study involving the Midwestern US population, an unusually high prevalence of type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disorders, and other autoimmune disorders were found in the moyamoya cohort which may point towards an autoimmune association. Chronic brain ischemia resulting from the narrowing is believed to be causing an overexpression of proangiogenic factors (fibroblast growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor) which, in turn, would cause the development of a fragile network of collateral vessels [1].

The following types of MMD (with the chromosome involved) have been described in the literature:

- MYMY1 - chromosome 3p

- MYMY2 - RNF213 gene on chromosome 17q25

- MYMY3 - chromosome 8q23

- MYMY4 - X-linked recessive condition characterized by MMD, short stature, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, and facial dysmorphism.

- MYMY5 - ACTA2 gene on chromosome 10q23

- MYMY6 with achalasia - GUCY1A3 gene on chromosome 4q32

History and Physical

Cerebral ischemic events in the form of TIA or ischemic infarcts are the commonest presentation of all Moyamoya patients. Intracerebral hemorrhage occurs mainly among adult patients with MMD. Seizures can present both among adults and children. Symptoms can be categorized on the basis of etiology: those due to cerebral ischemia (i.e., stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), and seizure) and those due to the growth of collateral vessels that compensate for ischemia (i.e. hemorrhage and headache).

- In the pediatric population, Moyamoya typically manifests with TIA or ischemic stroke. Attacks are usually precipitated by hyperventilation during crying, playing a wind instrument, or eating hot noodles. Hyperventilation decreases carbon dioxide, leading to cerebral vasoconstriction and aggravating cerebral hypo-perfusion. Children could also suffer from an intellectual disability. Deterioration of cognition is in a linear relationship with the number of strokes and chronic hypoxemia from a progressive narrowing of the cerebral vasculature [2].

- In addition to TIA or ischemic strokes, adults also frequently present with hemorrhagic stroke. Hemorrhage mainly results from a rupture of fragile moyamoya collaterals and seen in deep areas of the brain, such as basal ganglia, periventricular deep white matter. Intraventricular hemorrhage is common due to the close proximity of the primary site of intracerebral hemorrhage [3].

- Seizures are common complications of either ischemic or hemorrhagic events.

- Migraine-like headaches are common in both, children and/or adults and occur probably from the stimulation of dural nociceptor by dilated trans-dural collaterals.

Evaluation

1) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI is one of the first tests to perform in the diagnostic algorithm because it is sensitive and noninvasive. MRI is usually helpful to determine hemorrhages and/or strokes in brain parenchyma. Old ischemic lesions are often seen as white matter hyperintensities in the distal vasculatures and/ border zone areas in FLAIR and T2 weighted sequences. Slowing of flow can be demonstrated by the linear hyperintensities following the sulcal pattern, known as 'ivy sign' in the FLAIR sequence[4].

2) Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA):

MRA is a gold standard test and provides preliminary information on cerebral arteries and the degree of narrowing. MRA also shows the development of collaterals around the steno-occlusive lesions in the form of 'puff of smoke'. Based on MRA, diagnosis can be formed as either probable or definite moyamoya disease. 'Probable moyamoya' is the presence of a unilateral occlusive process in adults while 'Definite moyamoya' is the bilateral occlusive process in adults and even a unilateral occlusion in children as the rate of progression from unilateral to bilateral occlusion among children is very high. 'Quasi-moyamoya disease' (also known as Moyamoya syndrome) is a unilateral and/or bilateral occlusive process in the association of any underlying disease. Moyamoya disease does not involve posterior circulation while moyamoya syndrome could involve the steno-occlusive process in the posterior circulation [4].

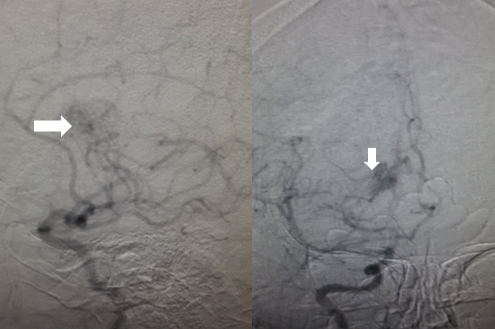

2) Conventional cerebral angiography:

- Cerebral angiography carries the highest specificity and provides accurate information about the area and degree of narrowing. However, use is limited owing to its nature of being an invasive technique and includes the uncertainty of diagnosis by MRI/MRA, presurgical evaluation, mapping postsurgical revascularization and/or worsening of narrowing during follow-up with noninvasive methods. Call for conventional angiography is purely subjective and depends on the knowledge as well as an experience of a neurologist.

- Suzuki and Kodoma classified the severity of moyamoya disease by progression of an occlusive process and the eventual appearance of collaterals based on serial cerebral angiographic evaluations and staged them, known as 'Suzuki stages of Moyamoya disease' which are mentioned under staging.

- Two kinds of collaterals are observed in angiography, each progressing from extracranial to the intracranial vasculature.

- Ethmoidal moyamoya: Commonly seen in children, these collaterals are perfused from ophthalmic artery and ethmoidal (anterior and posterior) arteries. Ethmoidal moyamoya communicates with basal moyamoya.

- Vault moyamoya: Commonly seen in adults, vault moyamoya are derived from transdural anastomosis of middle meningeal and superficial temporal arteries. Both types are directly proportionate to the angiographic stages of disease progression in children. Proof of co-relation among adults is not clear [4].

3) Transcranial Doppler (TCD):

TCD is an adjunctive method for monitoring cerebral hemodynamics and data of its ability to determine the stage and/or treatment method is scarce. Additionally, it is operator dependent, hence, it is not as useful as MRI, MRA or conventional angiography. Major parameters of monitoring using TCD are mean blood flow velocity and the pulsatility index [5].

4) Electroencephalography (EEG):

EEG evaluations are necessary for patients presenting with seizures. Suzuki and Kodoma mentioned a distinctive EEG finding among ~50% of moyamoya patients, known as the 'Rebuild-up' phenomenon. The rebuild-up phenomenon is referred to as a reappearance of slow waves of higher amplitude (normally seen during hyperventilation), within 20-60 seconds following termination of hyperventilation which is not seen in any other pathology. Rebuild-up is different than initial slowing due to hyperventilation and signifies the diminished blood flow. Slowing due to rebuild-up is resolved in approximately 10 minutes [6].

5) Cerebral perfusion measurement:

Important tools are single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and xenon-enhanced CT and MRI based methods. Xenon-enhanced CT and MRI based methods include positron emission tomography scan (PET scan) and arterial spin labeling. Both normally shows,

- Increase in oxygen fraction extraction

- Reduction of global cerebral blood flow with posterior cerebral flow distribution

- Impaired cerebrovascular reactivity to carbon dioxide and acetazolamide in ICA territory, suggesting low cerebrovascular reserve [7]

Apart from the mentioned above, diagnostic tests specific to the other conditions are required if moyamoya syndrome is suspected.

Treatment / Management

It is important to keep in mind that there is no curative treatment for moyamoya disease. Early diagnosis of moyamoya disease coupled with timely surgical intervention is of utmost importance as medical therapies act only as secondary prevention and do not halt disease progression. Both, medical and surgical treatments are directed towards improving cerebral blood flow. Acute therapy for strokes and/or intracranial bleeding is performed as per standard protocols.

1) Conservative management:

Conservative management is mainly directed towards maintaining cerebral blood flow and preventing further strokes. Aspirin has been conventionally used among patients of moyamoya disease to prevent further strokes. However, there is no evidence of a potential benefit of antiplatelet use to stroke prevention since the mechanism of MMD does not involve an endothelial damage and thereby platelet adhesion. Nevertheless, many neurologists around the world use aspirin towards mitigating the chances of further strokes in light of other risk factors and as a maintenance therapy to prevent thrombosis and thromboembolism from the stenosed portion of vessels after surgical revascularization. The usual dose of 50-100 mg is recommended.

Headaches and seizures are usually managed by symptomatic treatments using analgesics and antiepileptic medications, respectively [8].

2) Surgical revascularization:

This is the only main treatment for MMD with deteriorating cerebral hemodynamics to improve the cerebral blood flow and prevent further strokes. Main indications for surgical revascularization are apparent cerebral ischemia, reduced regional cerebral blood flow and decreased cerebral vascular reserve in perfusion studies. However, every case is evaluated separately as decisive factors may vary from case to case. Surgery is more beneficial for children since the pediatric form of MMD is usually rapidly progressive.

- Indirect revascularization: This is an easier method to perform but the time to improve the cerebral blood flow is longer than the direct revascularization. Major techniques used under this method are encephalomyo synangiosis (EMS) where the supply comes from the deep temporal artery and encephalo-duro-arterio synangiosis (EDAS) with the supply comes from superficial temporal artery. Encephalo-myo-arterio synangiosis (EMAS), encephalo-duro-arterio-myo synangiosis (EDAMS) and encephalo-galeo synangiosis (EGS) are variants of EMS and EDAS. The occipital artery can be used as an indirect bypass in case of MMD involving posterior circulation.

- Direct revascularization: Superficial temporal artery is used as the main supply vessel in direct bypass. Direct vascularization is technically more difficult to perform and requires a highly skilled surgeon but the improvement in the cerebral blood flow is noted immediately following the surgery [8]],[9].

Differential Diagnosis

- Anterior circulation stroke

- Basilar artery thrombosis

- Cavernous sinus syndromes

- Fibromuscular dystrophies

- Pediatric craniopharyngioma

Staging

Suzuki stages explain the process from the beginning of stenosis in the terminal portion of ICA and the appearance of a deep but fragile network of collaterals (moyamoya) to the reduction of moyamoya vessels with the simultaneous development of supply from external carotid artery branches. This fragile network of collaterals mainly develops from thalamoperforating and lenticulostriate perforating arteries. Suzuki stages of moyamoya disease are mentioned below.

Stage 1: 'Narrowing of carotid fork'. On the angiographic exam, only the terminal portion of the internal carotid artery is stenosed.

Stage 2: 'Initiation and appearance of basal moyamoya'. On the angiographic exam, stenosis of all the terminal branches of ICA (ACA and/or MCA) and deep moyamoya vessels are seen.

Stage 3: 'Intensification of basal moyamoya'. On the angiographic exam, deep moyamoya vessels are intensified. MRA taken during this stage shows a "puff of smoke" appearance. The deflection of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and middle cerebral arteries (MCA) is noted.

Stage 4: 'Minimization of basal moyamoya'. On the angiographic exam, deep moyamoya vessels begin to regress while transdural collaterals begin to appear. The deflection of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) is noted.

Stage 5: 'Reduction of moyamoya'. On the angiographic exam, continued regression of deep moyamoya vessels and progression of transdural collateral vessels are noted.

Stage 6: 'Disappearance of moyamoya'. On the angiographic exam, deep moyamoya vessels have vanished and there is complete occlusion of the ICA. Blood supply to ACA and MCA areas is derived mainly from the external carotid artery [1].

Prognosis

The overall prognosis is variable. Two-thirds of patients with Moyamoya disease have a symptomatic progression over five years with poor outcomes. Progression of the occlusive process continues regardless of symptom severity, ongoing treatment, age, sex, type and location of the disease. However, data from the North American series shows 13.3% and 1.7% of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, respectively. Factors that may show a poor prognosis could be but not limited to: hemorrhagic strokes at presentation, female gender, familial form of onset and pediatric age of onset. Concomitant thyroid disorder and smoking impacts negatively on overall prognosis in MMD. Early surgical revascularization has a preferable prognosis [1].

Complications

Mainly perioperative complications are there.

- Intraoperative ischemic stroke (in MMD with advanced Suzuki stage)

- Postoperative ischemic stroke with the permanent neurologic deficit (0.9% -8% of patients, more frequent in adults)

- Hemorrhagic stroke (0.7%-8% of patients)

- Postoperative epidural hematoma (4.8% of the pediatric population)

- Hyper-perfusion syndrome after direct vascularization (in 21.5% -50% of patients)

- Scalp problems, majorly scalp ischemia (17.6%- 21.4% of patients) [8][9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

MMD is a relatively rare neurological disorder that is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes neurology nurses. It is important to keep in mind that there is no curative treatment for moyamoya disease. Early diagnosis of moyamoya disease coupled with timely surgical intervention is of utmost importance as medical therapies act only as secondary prevention and do not halt disease progression. Both, medical and surgical treatments are directed towards improving cerebral blood flow. Acute therapy for strokes and/or intracranial bleeding is performed as per standard protocols.

The outcomes for patients with MMD are guarded. Hemorrhagic strokes are not uncommon resulting in significant disability. Patient education on lifestyle changes is highly recommended.