Introduction

The neural crest is a collection of multipotent stem cells located at the side of the neural tube proximal to the epidermal layer after neurulation. These cells migrate throughout the embryo using a variety of mechanisms and give rise to a large range of cell types. Given the diversity of the cells that arise from the neural crest, its pathologies, known as neurocristopathies, can affect many different systems.

Understanding the complex methods behind neural crest cell migration, differentiation, and pathology can help with better understanding both human and cell development. The multipotency of neural crest stem cells also provides interesting avenues for research and potential medical applications.[1] The presence of a neural crest is a defining feature of vertebrates, and researchers often employ animal models in neural crest research.[2]

Structure and Function

Neural crest cells are present in and around the dorsal neural tube after its closure. These cells form via signaling between neural and non-neural ectoderm and undergo an epithelial to mesenchymal transition before beginning migration.

The location of their migration provides the signaling to aid in their differentiation. Examples include the Kit gene, which promotes differentiation into melanocytes and BMP signaling, which helps develop the autonomic nervous system.

Neural crest cells are precursors to a wide variety of tissues, including the ectodermal derivatives of melanocytes, sensory and autonomic ganglion neurons, and Schwann cells. There are also a wide variety of ectomesenchymal derivatives including neuroendocrine chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, dental mesenchymal stem cells (odontoblasts), endoneural fibroblasts, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, and the cartilage and bone of the craniofacial area. One can roughly determine the function of the resulting cells from where they arise, and dysfunctions include not only congenital defects but various cancers as well.[3]

Embryology

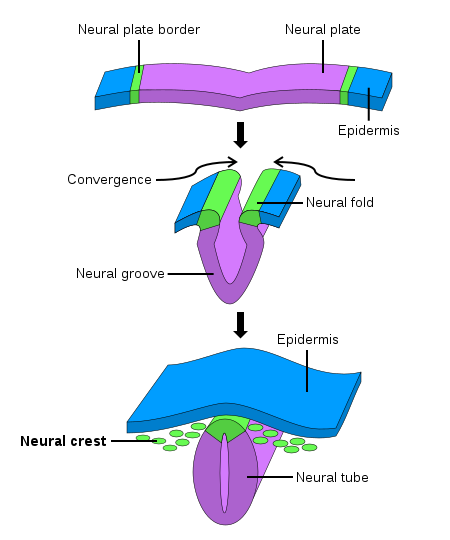

During early fetal development, the neural stage starts with the formation of the primitive neural plate. The neural plate then folds and forms the neural tube, which becomes the ultimate central nervous system. The neural crest arises from each side of the neural plate, between the neural and non-neural ectoderm. When neurulation progresses, and the neural plate folds upwards to meet at the top to form the neural tube, the neural crest becomes separated from the neural tube in a process termed delamination. Subsequently, these neural crest cells migrate to their final destination to become a wide variety of ectodermal and ectomesenchymal derivatives.

The neural crest begins to migrate soon after neural tube closure, approximately twenty-one to twenty-eight days after fertilization.[4] The neural crest and its derivatives can divide into four categories, based on their location in the embryo and the structures to which they give rise.

The cephalic or cranial neural crest, arising from the diencephalon to the third somite, forms bones and cartilage in the head and neck as well as some connective tissues in this area. They also form pigment cells and the peripheral nervous system. The cardiac neural crest, a subset of the cephalic, runs from the otic level to the fourth somite. It contributes to the outflow tract of the heart. The truncal neural crest, caudal to the fourth somite, provides pigment cells, some peripheral nervous system cells, and the endocrine cells of the adrenal gland. The enteric neural crest runs along somites one through seven and forms the enteric peripheral nervous system.[5]

Clinical Significance

Neurocristopathies

Issues that arise during the formation and migration of neural crest cells are known as neurocristopathies, with varying effects depending on the location of the dysfunction. The multitude of loci involved in movement and differentiation of neural crest cells makes determining etiology different, though many neurocristopathies follow Mendelian inheritance. The neurocristopathy examples here are listed by the location of their origin from the neural crest, though there are many more disease processes that may also involve multiple parts of the neural crest.[6]

Cranial Neurocristopathies

Sturge-Weber syndrome - This somatic disease characteristically demonstrates by a red, “port-wine” birthmark, leptomeningeal angiomas and early-onset glaucoma, and typically presents in infants.[7] The distribution of the birthmark follows neural crest cell migration, and the leptomeningeal angiomas involve cells of neural crest origin. A gene mutation specific to this disorder, GNAQ, has been connected to other neural-crest cell disorders, such as melanoma.[1]

Treacher Collins syndrome - This autosomal recessive disorder has various craniofacial abnormalities as well as middle and external ear issues that may result in conductive hearing loss. Specifically, the orofacial clefting seen in Treacher Collins is due to problems with the fusion of the facial prominences and/or the palatal shelves, both of which originate from the neural crest.[1]

Cardiac Neurocristopathies

Heterotaxy Syndrome - This syndrome refers to a variety of potential pathologies where organs and in the thorax and abdomen are abnormally arranged. The heart is especially affected, as congenital heart defects appear in approximately 80% of heterotaxy patients. There are many genes implicated in the many presentations of heterotaxy, and the majority of them are involved in nodal signaling, which aids in the migration of neural crest cells.[1]

Truncal Neurocristopathies

Congenital Central hypoventilation syndrome - This autosomal dominant disorder results in dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, shallow breathing, and the development of cancer. The gene involved, Phox2b, is expressed in the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, and neural crest cells in the gut. Animal models have connected this gene to signaling pathways that aid in the development of neural crest cells.[1]

Familial Dysautonomia - This autosomal recessive disorder presents with progressive peripheral neuropathy with tachycardia, vomiting, decreased pain and temperature, and blood pressure lability. These symptoms result from peripheral nervous system dysfunction, specifically neurogenesis. The peripheral nervous system arises from the neural crest, and familial dysautonomia results from the death of these neurons during development.[1]

Enteric Neurocristopathies

Hirschsprung Disease - This autosomal dominant developmental disorder typically shows an absence of enteric neurons in the enteric nervous system. The pathogenesis of Hirschsprung disease is the inability of neural crest cells to migrate to various parts of the distal intestine. However, the specific etiology is less well-characterized, and Hirschsprung disease is associated with many other syndromes and genes.[1]

Neural Crest Cancers

The ability of the neural crest cells to migrate and differentiate seems to make their derivatives more prone to carcinogenesis, and neural crest cells give rise to many different cancer lineages. These cancers can be categorized based on the neural crest cells from whence they arise.

Sympathetic Cell Cancers

Neuroblastoma - The most common tumor of infancy with a variable prognosis. This tumor originates from a sympathoadrenal neural crest cell that has not yet differentiated further. Primary neuroblastomas typically present in the adrenal medulla and sympathetic ganglia. Symptoms result from compression of adjacent structures or paraneoplastic syndromes.[8]

Paraganglioma and Pheochromocytoma - These tumors are highly vascularized and arise from paraxial autonomic ganglia or chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla. They typically secrete catecholamines which lead to tachycardia, hypertension, and increased stroke risk, and may also compress nearby structures.[8]

Melanocytic Cancers

Malignant melanoma - The most common cancer of neural crest cells, melanoma has a variety of risk factors. Melanomas tend to metastasize aggressively, which is potentially due to melanocyte expression of certain epithelial-mesenchymal transition factors from neural crest cell development. In animal models, certain melanoma cell lines have been shown to follow neural crest cell migration pathways.[9]

Schwann Cell Cancers

Neurofibromatosis - Neurofibromatosis types I and II typically involve Schwann cells, which are of neural crest origin. They have autosomal dominant inheritance and often sporadically mutate.

Neurofibromatosis type I involves the NF1 gene, which codes for neurofibromin, a negative RAS activator. Symptoms include neurofibromas, cafe-au-lait patches on the skin, optic gliomas, hamartomas of the iris, and dysplastic scoliosis.

Neurofibromatosis type II is due to a mutation in the NF2 gene, which codes for Merlin, a tumor suppressor gene that also acts in cell adhesion. This disease characteristic presentation includes schwannomas, especially bilateral schwannomas, in the vestibular nerve.[8]

Cancers from Multiple Lineages

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia - This cancer syndrome is autosomal dominant and involves endocrine cells. Of the three variants, only 2A and 2B are of neural crest origin. They are characterized by mutations in the RET, which aids in the migration and colonization of neural crest cells into the foregut. MEN2A is often associated with medullary thyroid cancer and pheochromocytomas. MEN2B is more aggressive and has ganglioneuromatosis, oral neuromas, and Marfanoid Habitus.[8]

Congenital Horner Syndrome

It is interesting to examine the uncommon condition of congenital Horner syndrome to understand the neural crest derivatives further. Horner syndrome is a syndrome resulting from a lesion of the oculosympathetic pathway. About 5% of all Horner syndrome is congenital, frequently caused by birth trauma or any pathology along the cervical sympathetic pathway. Clinically there is partial ptosis, miosis and absent sweating of the face on the side of the lesion. When Horner syndrome occurs before the age of two, there will be heterochromia iritis with the iris on the side of lesion unpigmented. This lack of pigmentation will result in the bluish color of that iris, similar to the iris color of white peoples; this is proof that pigment-producing cells of the iris derive from the neural crest. Congenital Horner syndrome is also associated with childhood neuroblastoma which is a neural crest-derived malignant neuronal tumor outside of the central nervous system.[10][11]