Continuing Education Activity

Splenomegaly is defined as the enlargement of the spleen measured by size or weight. The spleen plays a significant role in hematopoiesis and immunosurveillance. The major functions of the spleen include clearance of abnormal erythrocytes, removal of microorganisms and antigens, as well as the synthesis of immunoglobulin G (IgG). The spleen also synthesizes the immune system peptides properdin and tuftsin. Approximately one-third of circulating platelets are stored in the spleen. The normal weight of the adult spleen is 70 g to 200 g, spleen weight of 400 g to 500 g indicates splenomegaly spleen weight greater than 1000 g is definitive of massive splenomegaly. This activity reviews the causes, evaluation, and management of splenomegaly and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of splenomegaly.

- Describe the typical history and physical exam findings in a patient with splenomegaly.

- Outline the treatment and management options for splenomegaly.

- Review interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance splenomegaly and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Splenomegaly is defined as the enlargement of the spleen measured by weight or size. The spleen plays a significant role in hematopoiesis and immunosurveillance. The major functions of the spleen include clearance of senescent and abnormal erythrocytes and their remnants, opsonized platelets and white blood cells, and removal of microorganisms and antigens. The spleen also serves as a secondary lymphoid organ and is the site for the maturation and storage of T and B lymphocytes, playing an important role in the synthesis of immunoglobulin G (IgG) by mature B-lymphocytes upon interaction with the T-lymphocytes. The spleen also synthesizes the immune system peptides properdin and tuftsin. Approximately one-third of circulating platelets are stored in the spleen. The normal position of the spleen is within the peritoneal cavity in the left upper quadrant adjacent to ribs 9 through 12. The normal-sized spleen abuts the stomach, colon, and left kidney.

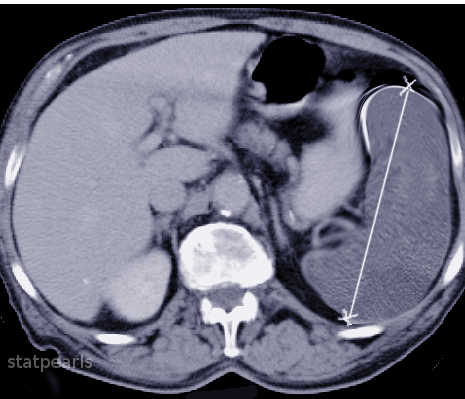

The size and weight of the spleen may vary and correlate with the weight, height, and sex of an individual, with larger spleen size seen in men compared to women and in heavier or taller individuals. A normally sized spleen measures up to 12 cm in craniocaudal length. A length of 12 cm to 20 cm indicates splenomegaly and a length greater than 20 cm is definitive of massive splenomegaly. The normal weight of the adult spleen is 70 g to 200 g; a spleen weight of 400 g to 500 g indicates splenomegaly and a spleen weight greater than 1000 g is definitive of massive splenomegaly. The normal-sized spleen is usually not palpable in adults. However, it may be palpable due to variations in body habitus and chest wall anatomy. Splenomegaly may be diagnosed clinically or radiographically using ultrasound, CT imaging, or MRI. Splenomegaly may be a transient condition due to acute illness or may be due to serious underlying acute or chronic pathology.[1][2][3]

Etiology

There are several potential causes of splenomegaly.

- Liver disease (cirrhosis, hepatitis): Parenchymal liver disease causes increased vascular pressure leading to an increase in spleen size.

- Hematologic malignancies (lymphomas, leukemias, myeloproliferative disorders): Neoplastic cells cause infiltration of the spleen leading to splenomegaly.

- Venous thrombosis (portal or hepatic vein thrombosis): This leads to an increase in vascular pressure leading to splenomegaly.

- Splenic congestion (venous thrombosis, portal hypertension, congestive heart failure).

- Cytopenias (autoimmune hemolytic anemia, immune-mediated neutropenia, Felty syndrome): Immune-mediated destruction of red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets lead to functional splenomegaly.

- Splenic sequestration (pediatric sickle cell disease, hemolytic anemias, thalassemias).

- Acute or chronic infection (bacterial endocarditis, infectious mononucleosis, HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, histiocytosis, abscess).

- Connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Adult-onset Still's disease, and some familial autoinflammatory syndromes).[4][5]

- Infiltrative disorders (sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, glycogen storage diseases).

- Splenic sequestration (pediatric sickle cell, hemolytic anemias, thalassemias).

- Focal lesions (hemangiomas, abscess, cysts, metastasis).

The mechanism underlying splenic enlargement varies based on the etiology. In the case of acute infectious illness, the spleen performs increased work in clearing antigens and producing antibodies and increases the number of reticuloendothelial cells contained within the spleen. These increased immune functions may result in splenic hyperplasia. In the case of liver disease and congestion, underlying illness causes increased venous pressure causing congestive splenomegaly. Extramedullary hematopoiesis exhibited in myeloproliferative disorders can lead to splenic enlargement (infiltrative splenomegaly).[6][7]

Splenic sequestration crisis (SSC) is a life-threatening illness common in pediatric patients with homozygous sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia. Up to 30% of these children may develop SSC, with a mortality rate of up to 15%. This crisis occurs when splenic vaso-occlusion causes a large percentage of total blood volume to become trapped within the spleen. Clinical signs include a severe, rapid drop in hemoglobin, leading to hypovolemic shock and death. Pediatric patients with sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia experience multiple splenic infarcts, resulting in splenic fibrosis and scarring. Over time, this leads to a small, auto-infarcted spleen, typically by the time patients reach adulthood. Splenic sequestration crisis can only occur in functioning spleens which may be why this crisis is rarely seen in adults. However, late adolescent or adult patients in this group who maintain splenic function may also develop a splenic sequestration crisis.

Epidemiology

Splenomegaly is a rare condition, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 2% of the total United States population. In adults, there has been no reported predominance in prevalence based on ethnicity, gender, or age. In Asia and Africa, tropical splenomegaly is very common. In older people, the capsule of the spleen is thin, thus the risk of rupture is higher.

Pathophysiology

Splenomegaly can be classified based on its pathophysiologic mechanism:

- Congestive, by pooled blood (e.g., portal hypertension)

- Infiltrative, by invasion by cells foreign to the splenic environment (eg., metastases, myeloid neoplasms, lipid storage diseases)

- Immune, by an increase in immunologic activity and subsequent hyperplasia (eg., endocarditis, sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis)

- Neoplastic, when resident immune cells originate a neoplasm (eg., lymphoma).

History and Physical

The most common physical symptom associated with splenomegaly is vague abdominal discomfort. Patients may complain of pain in the left upper abdomen or referred pain in the left shoulder. Abdominal bloating, distended abdomen, anorexia, and/or early satiety may also occur. More commonly, patients will present with symptoms due to the underlying illness causing splenomegaly. Constitutional symptoms such as weakness, weight loss, and night sweats suggest malignant illness. Patients with splenomegaly due to acute infection may present with fever, rigors, generalized malaise, or focal infectious symptoms. Patients with underlying liver disease may present with symptoms related to cirrhosis or hepatitis. Symptoms of anemia (lightheadedness, dyspnea, or exertion), easy bruising, bleeding, or petechiae may indicate splenomegaly due to the underlying hemolytic process.

Physical examination of the spleen is performed with the patient in supine and right lateral decubitus position with neck, hips, and knees flexed. This positioning relaxes the abdominal wall musculature and rotates the spleen more anteriorly. Light fingertip pressure is applied below the left costal margin during deep inspiration. The examiner may feel the rounded edge of the spleen pass underneath the fingertips at maximum inspiration. The exam is abnormal if the spleen is palpated more than 2 cm below the costal margin. In massive splenomegaly, the spleen may be palpated deep into the abdomen, crossing the midline of the abdomen, and may even extend into the pelvis. Studies have shown that normal sized spleens may be palpable in approximately 3% of adults.

Patients may have an abnormally palpable spleen with or without exam findings of contributing underlying illness. Patients with splenomegaly due to acute infection may have exam findings consistent with infectious mononucleosis, endocarditis, or malaria. Exam findings of petechiae, abnormal mucosal bleeding, or pallor may accompany hematologic diseases. Jaundice, hepatomegaly, ascites, or spider angiomata may be present in patients with liver disease. Patients with rheumatologic diseases may present with joint tenderness, swelling, rash, or an abnormal lung exam.

Evaluation

A combination of serum testing and imaging studies may definitively diagnose splenomegaly and the underlying cause. Derangement in the complete blood (cell) counts and morphology, including WBC, RBC, and platelets, will vary based on the underlying disease state. Abnormalities in liver function tests, lipase, rheumatologic panels, and disease-specific infectious testing aid in the diagnosis of causative disease.[8] Hypersplenism may present with leukopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia.

Imaging may be used to diagnose splenomegaly and elucidate its underlying cause. The spleen has a similar attenuation as the liver when measured on CT imaging. In addition to diagnosing splenomegaly (a splenic measurement of greater than 10 cm in craniocaudal length), abdominal CT may detect splenic abscess, mass lesions, vascular abnormalities, cysts, inflammatory changes, traumatic injury, intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy, or liver abnormalities.

Ultrasound is a useful imaging modality in measuring the spleen and spares the patient radiation from CT imaging. Normal spleen size measured via ultrasound is less than 13 cm superior to the inferior axis, 6 cm to 7 cm in the medial to lateral axis, and 5 cm to 6 cm in the anterior to posterior plane.

MRI, PET scans, liver-spleen colloid scanning, splenectomy, and splenic biopsy may be indicated in certain cases.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of splenomegaly is targeted at treating the underlying disease and protecting the patient from complications of splenomegaly itself. Patients with splenomegaly from any cause are at increased risk of splenic rupture, and increased attention must be made to protect the patient from abdominal trauma. Treatment ranges from abdominal injury avoidance in young healthy patients with splenomegaly due to infectious mononucleosis to splenectomy of a massively enlarged spleen in a patient with hairy cell leukemia. Likewise, the prognosis is largely dependent on the underlying disease state.[9][10]

Splenic sequestration is seen in sickle cell anemia is often managed with blood transfusions/exchange transfusions. Sometimes splenectomy is required for ITP. Low dose radiation therapy can also shrink the spleen size in patients with primary myelofibrosis.

Patients who undergo splenectomy are at increased risk of infections secondary to encapsulated organisms such as Haemophilus Influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis. Vaccinations against these organisms are highly recommended in patients who have undergone splenectomy. Careful attention must be paid to post-splenectomy patients presenting with febrile illnesses as they may require more aggressive, empiric antibiotic therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

There are several potential causes of splenomegaly, and careful and thorough evaluation is often needed to find the underlying cause of splenomegaly.

These include:

- Cirrhosis

- Hepatitis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Felty syndrome

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Lymphoma

- Sickle cell anemia

Liver disease (cirrhosis, hepatitis) is one of the most common causes, and a history of liver disease, abnormal physical exam findings, and elevated liver enzymes, in addition to abnormal liver imaging, can help diagnose liver diseases.

Hematologic malignancies and metastasis shall be especially considered in patients with constitutional symptoms and weight loss. Abnormal peripheral blood smear and biopsy can assist in diagnosing malignancies.

Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) frequently are associated with splenomegaly. In RA, the presence of splenomegaly, in addition to neutropenia, is termed Felty syndrome.

Acute and chronic infections, including viral, bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial infections, can all cause splenomegaly and shall be carefully ruled out.

Cytopenias and diseases causing splenic sequestration can be ruled out by complete blood counts, peripheral blood smear, and hemoglobin electrophoresis.

Infiltrative disorders such as glycogen storage diseases are rare cause of splenomegaly and shall be considered if other more common causes are ruled out in patients with other clinical features consistent with these glycogen storage diseases.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with splenomegaly depends on the condition causing the enlargement. Regardless of the underlying etiology, the risk of rupture, even with minor trauma, is high in patients with an enlarged spleen.

Complications

Splenic rupture is the most feared complication of splenomegaly. Patients are advised to avoid high-impact or contact sports to minimize this risk. Cytopenias due to splenomegaly are another potential complication. Most of these can be minimized with splenectomy if indicated.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with enlarged spleens are advised to avoid high-impact or contact sports to avoid the risk of splenic rupture.

Once a patient undergoes splenectomy, they should be advised of the higher risk of infections, and proper immunization should take place to minimize this risk.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with splenomegaly are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a radiologist, internist, hematologist, oncologist, surgeon, nursing staff, and sometimes other specialists such as rheumatologists and gastroenterologists. Due to the high risk of rupture, patient education is crucial, and contact sports shall be avoided in patients with splenomegaly.

The nursing staff should educate the patient on the risk of infections if they undergo splenectomy. Vaccination against encapsulated organisms is highly recommended prior to the splenectomy. All patients who have had a splenectomy should wear a medical alert bracelet explaining the absence of a spleen. Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended in post-splenectomy patients undergoing surgical procedures. Further, careful attention must be paid to post-splenectomy patients presenting with febrile illnesses as they may require more aggressive, empiric antibiotic therapy.

All patients with splenomegaly should be educated about the signs of splenic rupture and when to seek medical assistance. Unlike a normal spleen, an enlarged spleen that has ruptured cannot be managed with observation. Close collaboration with the team members is important to ensure that patients without a spleen have good outcomes. Most patients have a good outcome after splenectomy.[11][12]