Introduction

The coronary arteries are the first vessels to branch from the aorta, and they provide a crucial supply of oxygen and nutrients to the layers of the heart. The right coronary artery and its branches mostly supply the right side of the heart, although they also reach part of the left atrium, a posterior portion of the left ventricle, and even the posterior third of the interventricular septum. Unlike vessels in peripheral locations of the body, these vessels dilate during exertion to meet the increased demands of the myocardium. However, the lack of anastomoses amongst the coronary arteries leaves the heart at risk of ischemia and infarction if blood flow through the vessels is severely compromised, such as with atherosclerosis.

Structure and Function

Structural overview

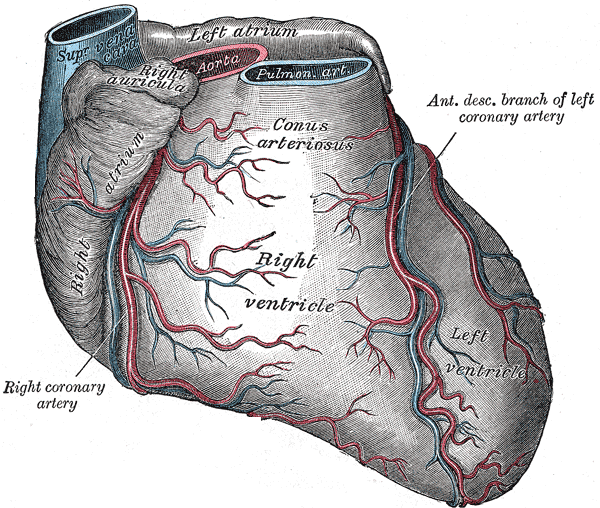

The right coronary artery finds its origin from the aorta immediately above the right (coronary) semilunar cusp of the aortic valve. It follows a course between the pulmonary trunk and right atrium in the right atrioventricular groove and curves around the acute angle of the heart. The major branches of the right coronary artery include the sinoatrial (SA) nodal branch, the right (acute) marginal branch, the posterior interventricular branch (commonly referred to as the posterior descending artery, PDA), and the posterolateral branch.[1][2][1]

The posterior interventricular and posterolateral arteries branch from the right coronary artery in about 70% of the population.[1] Individuals with this configuration are considered to have a “right dominant” coronary circulation. If these arteries arise from the circumflex branch of the left coronary artery, the heart has a “left dominant” orientation. When both the right and left coronary arteries contribute to these branches, the heart has a “balanced” circulation.

Histology

The coronary arteries are composed of three layers: tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia.

The tunica intima is the lining inside the vessels comprised of the endothelium, sub-endothelium, and internal elastic lamina. Simple squamous cells make up the inner-most layer, which functions not only as a barrier allowing blood to flow smoothly but also for pinocytosis, diapedesis, and secretions into the lumen or back into the smooth muscle to produce nitrous oxide (NO). A break in any part of the endothelial lining exposes blood to the subendothelial layer which starts the clotting mechanism. Discontinuity of the simple squamous endothelium can initiate the process of atherosclerosis, where fat buildup causes the endothelium to rip or tear, which initiates the formation of a clot, and leads to plaque buildup. Underneath the sub-endothelium is a thick internal elastic lamina.

The tunica media is the name given the middle layer of the vessels, comprised of layers of smooth muscle cells arrayed in a hexagonal pattern to allow for better contractility.[3] There are typically around five layers of smooth muscle, with few elastic fibers, collagen, and proteoglycans.[3] A thick external elastic lamina generally is only seen in large arteries.

The tunica adventitia is an outer connective tissue layer supporting the vessel itself and is formed of loose connective tissue (fibroblasts, collagen), vessels, and nerves. Vasa vasorum are vessels that supply larger vessels, and vasomotor nerves (nervi vascularis) support vessel contraction.

Functional overview

Approximately 5% of cardiac output supplies the heart muscle through the coronary arteries.[4] Blood from the SA nodal branch supplies the SA node, and the right marginal artery supplies the right ventricle. The posterior interventricular artery runs alongside the middle cardiac vein down the posterior interventricular sulcus and supplies the AV node, the posterior 1/3 of the interventricular septum, the posterior 2/3 walls of the ventricles, and is the only vessel supplying the posteromedial papillary muscle.

Blood flow

A linear relationship exists between myocardial oxygen consumption and coronary blood flow. At rest, the heart receives 250-300 ml/min of total blood flow. This increases to 1,000-2,000 ml/min during exercise. Control of heart vessels relies mainly on local metabolic control from adenosine released from myocardial cells. During exercise, the energy demands of the heart increase, and more adenosine is produced, which leads to vasodilation and higher flow rates to meet the requirements of the heart. Coronary arteries also have a high abundance of ß2 adrenergic receptors, which result in vasodilation when stimulated.

Although both arteries branch from the aorta with the same blood pressure, the left, and right coronary arteries exhibit different blood rates. The left coronary flow occurs mostly during diastole when the myocardium is relaxed, and pressure in the coronary artery is higher than the left ventricle. In systole, the pressure in the left atrium is nearly the same as the aortic pressure, so little flow or even a mild reversal of flow may occur (known as the “throttle effect”). This is the primary mechanism for why flow in the left coronary artery is dependent on diastole, but the other factors that contribute to this include the blood vessels coursing from the epicardium to the endocardium getting squeezed during systole, and eddy currents in the sinus of Valsalva during systole decreasing flow to the coronary arteries. In contrast, flow in the right coronary arteries is not diastole-dependent. This is because pressures generated in the right heart are relatively lower, so the pressure inside the right coronary arteries will be higher than the pressure in the walls of the heart even both systole and diastole, which will produce a more uniform rate of flow.

Embryology

The coronary arteries develop within the atrioventricular and interventricular grooves, and after separation of the aorta and pulmonary artery, they fuse with buds from the right and left semilunar cusps (also known as the sinus of Valsalva) to provide blood supply to the myocardium.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply to coronary arteries is provided in part by blood flowing within the vessels themselves, and large arteries receive their supply by a network of vasa vasorum microvessels. The vasa vasorum is thought to play a role in the development of coronary atherosclerosis.[5]

Nerves

Parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerve (CN X) may vasodilate coronary resistance vessels. Sympathetic fibers may favor vasoconstriction of the coronary resistance vessels via alpha adrenoreceptors. However, local metabolic control of adenosine released from myocardial cells typically overshadows this effect, resulting in net vasodilation on exertion.

Muscles

The tunica media, the middle layer of coronary arteries, is made of layers of smooth muscle.

Physiologic Variants

Physical variations of the coronary artery circulation include a left and right coronary artery that share a common trunk, an AV node that is supplied by the left circumflex artery, or rarely an AV nodal branch from both the right coronary artery and the left circumflex artery. The posterior interventricular artery (PDA - for posterior descending artery) may arise from the left circumflex artery in 10% of the population, or both the left circumflex artery and right coronary artery in 20% of the population.[1] The SA nodal artery arises from the left coronary artery in 34% of the population.[1]

Surgical Considerations

Revascularization of the heart is achievable with a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).[6] With a CABG procedure, blood flow to an obstructed area of the heart can be improved with vessel grafts from elsewhere in the body into the coronary artery circulation. The two vessels commonly used include the left internal thoracic artery (also known as the left internal mammary artery, LIMA), or the great saphenous vein from the leg. Alternatively, a physician may decide to use percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as a non-surgical option to treat stenosis of a coronary artery. This procedure may include the insertion of stents to widen a partially occluded vessel.[7]

Clinical Significance

There is typically no anastomosis of posterior and anterior interventricular arteries, so occlusion of a coronary artery can have significant effects on the heart. Ischemic heart disease has as its fundamental characteristic an imbalance between the supply and demand of oxygenated blood for cardiac tissue. This commonly occurs when the blood supply to the heart tissue is diminished, such as in coronary artery atherosclerosis where the lumen of a major epicardial artery is obstructed by atherosclerotic plaque and potentially a superimposed thrombosis.[8] Ischemic syndromes include angina pectoris, acute myocardial infarction (MI), and sudden cardiac death.

Coronary artery occlusion is most common in the left anterior descending artery (LAD, also known as the left anterior interventricular artery), but it may also occur in the right coronary arteries. A posterior wall MI can occur with occlusion of the posterior descending or distal right coronary arteries, which will inhibit or block the blood supply to the posterior walls of the left and right ventricles and a third of the interventricular septum. Unlike the anteromedial papillary muscle, which receives blood from the anterior interventricular artery and the left circumflex artery, the posteromedial papillary muscle is supplied only by the posterior interventricular artery. This makes it more susceptible to coronary ischemia as well. The clinical significance of this would be possible mitral regurgitation. Another type of MI is an inferior wall infarct, which occurs from occlusion of the right coronary artery. Because it is the innermost layer of tissue in the heart wall, the endocardium is usually the layer most severely impacted with infarction. Infarction resulting from blockage of the right coronary artery or any of its branches that supply the SA or AV node may affect the ability of the node to fire and control the heartbeat which would manifest as nodal dysfunction like bradycardia or heart block.[9]

Other Issues

Coronary angiography can be used to assess the structure of coronary arteries.[10]