Introduction

Transpulmonary pressure (TPP) is a topic in pulmonary physiology that has both a traditional definition and a more modern or alternative definition. According to the conventional definition, TPP is the pressure difference across the entire lung, from the opening of the pulmonary airway to the pleural surface.[1] According to the alternative definition, TPP is the pressure difference only across the lung tissue. This measurement is the pressure difference between the alveolar space and the intrapleural space. In other words, according to the alternative definition, the TPP is the force that opposes the inward elastic recoil of the lung at rest or the distending pressure of the lung parenchyma.[1][2]

Issues of Concern

As such, the alternative definition does not take into consideration the pressure differences created by the upper airways and the breathing mechanics as the traditional description does.[1] This vital difference comes into play, particularly in mechanically vented patients and in patients with a variety of pulmonary conditions, as discussed below. This article aims to elaborate on the alternative definition of TPP.

Cellular Level

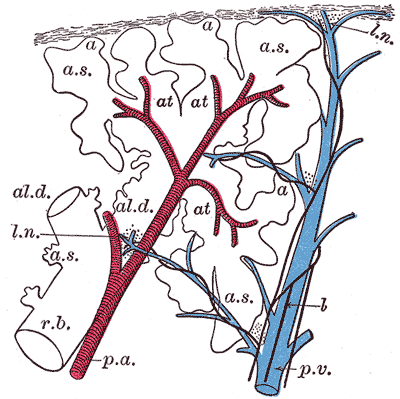

At the cellular level, TPP is the pressure differential exerted at the interface between the alveolar surface and the pleural space. Since TPP is the transmural pressure across the lungs, by convention, it is measured as the pressure on the inside of the structure minus the pressure on the outside of the structure. In this case, this would translate to alveolar pressure minus intrapleural pressure. The change in TPP also affects the compliance of the lung. Lung compliance is the change in lung volume produced by a given change in TPP. In order words, a highly compliant lung will more easily expand when a more significant TPP is applied. In contrast, a stiff lung will require a more considerable TPP to produce an inevitable increase in lung volume.[3][4]

Development

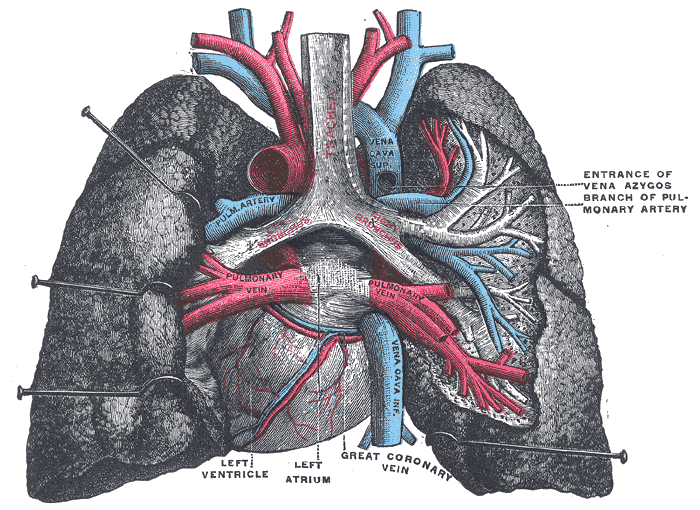

Embryologically, the pleura derives from a layer of mesothelial cells, which envelops the outer surface of the lungs as well as the inner surface of the thoracic cavity, thereby creating the pleural space.[5] The pleural cavity arises between the 4th and 7th week of embryologic maturation.[6]

Below the layer of the mesothelial cells is a matrix of elastic fibers, collagen, blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels, which allow movement of the chest wall and lung with minimal friction due to the presence of pleural fluid and the lubricating properties of the mesothelial cells.[5] The pleura also acts as a barrier to the spread of infections.[5] The net movement of pleural fluid is from the costal pleural to the mediastinal and interlobar region, where fluid resorption occurs via lymphatic stomata on the parietal pleural surface.[6] Depending on which structures are opposing the pleura, the pleura can subclassify as diaphragmatic, mediastinal, or costal.

Organ Systems Involved

TPP primarily involves the respiratory and musculoskeletal systems. The central nervous, integumentary, vascular, and lymphatic systems also affect the TPP.

Function

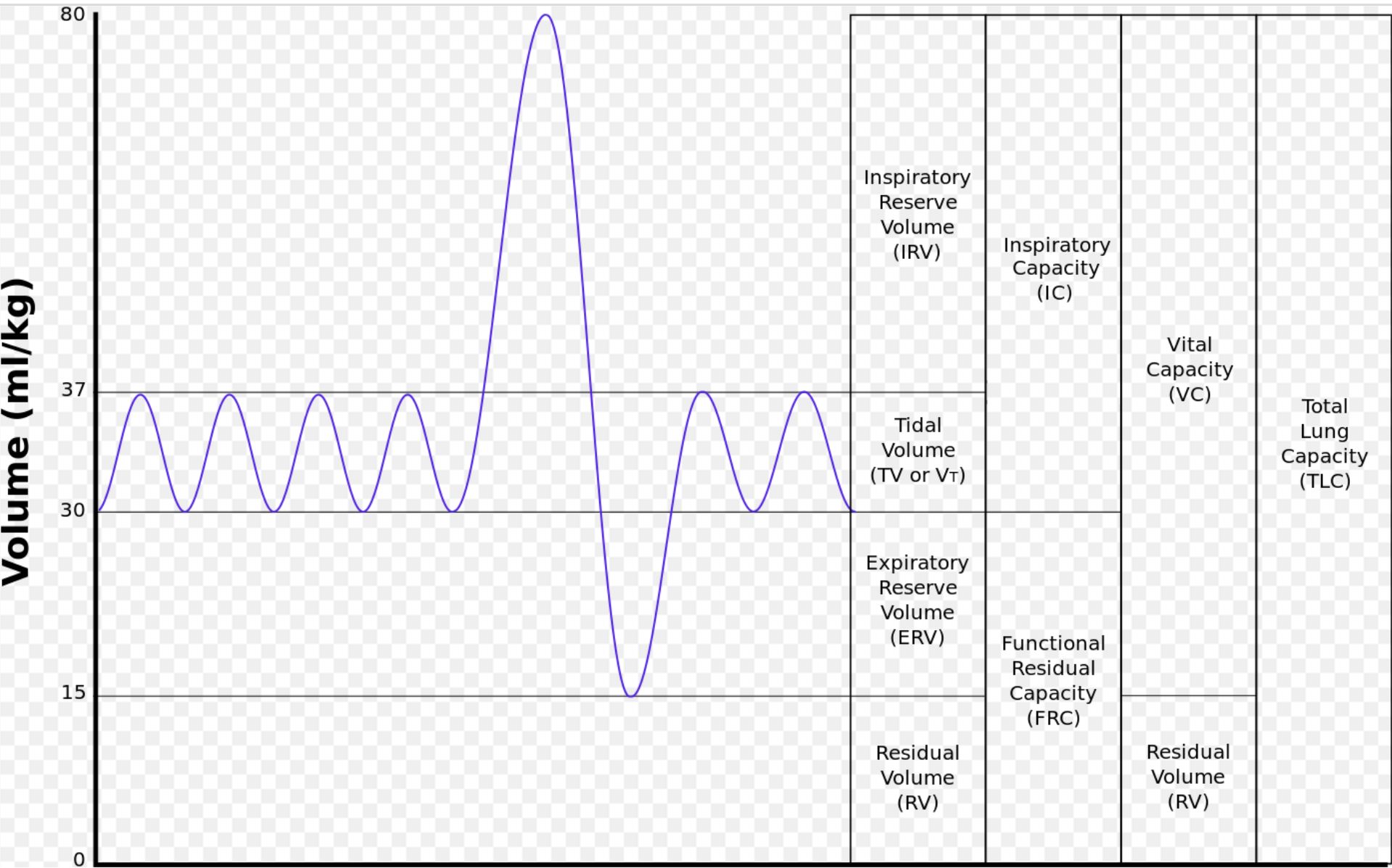

To easily understand respiratory physiology, lungs can be compared to balloons. Balloons are elastic structures that tend to collapse if nothing is preventing the air from inside to leak out. On the other hand, the chest wall also has elastic recoil, which, at rest, tends to expand. The pleural space, filled with pleural fluid, is what juxtaposes the two surfaces. The pressure difference between the alveolar pressure and the intrapleural pressure is the transmural pressure across the lung (i.e., TPP). The pressure difference between the intrapleural pressure and the atmospheric pressure is the transmural pressure across the chest wall (CWP). At rest, the TPP is approximately 4 mmHg, and the CWP is approximately -4 mmHg. In other words, at rest, the inward elastic recoil of the lung exactly opposes the outward acting elastic recoil of the chest wall, and there is no net airflow.[7][8][9]

Mechanism

During inspiration, the diaphragm and the inspiratory intercostal muscles actively contract, leading to the expansion of the thorax. The intrapleural pressure (which is usually -4 mmHg at rest) becomes more subatmospheric or more negative. As a result, the TPP increases, given that TPP is equal to alveolar pressure minus the intrapleural pressure. An increase in TPP during inspiration leads to expansion of the lungs, as the force acting to expand the lungs, i.e., the TPP, is now superior to the inward elastic recoil exerted by the lungs. Expansion of the lungs creates subatmospheric pressure in the alveoli, leading to airflow into the alveoli down the pressure gradient. According to the Boyle law, since the pressure exerted by a stable number of gas molecules at a given temperature is inversely proportional to the volume of a container, the alveolar pressure will decrease when the lungs expand. As long as there is a difference between the TPP and the elastic recoil of the lungs, there is airflow. At the end of inspiration, the more inflated lungs exert a higher elastic recoil due to their size, which equals the increased TPP, at which point equilibrium is re-established, and airflow ceases.

During passive expiration, the diaphragm and inspiratory intercostal muscles cease contracting and relax, resulting in inward recoil of the chest wall and a decrease in the lung size. The intrapleural pressure increases to its baseline value, which decreases the TPP. At this point, the TPP holding the lungs open is smaller than the elastic recoil exerted by the more inflated lungs, resulting in the passive recoil of the lungs to their baseline dimensions. Decreased lung dimensions lead to the alveolar pressure surpassing the atmospheric pressure, as explained by the Boyle law. As a result, air flows from the alveoli to the atmosphere until reaching a new equilibrium between the two pressures.

Expiration of air can also be enhanced by contraction of the abdominal muscles and a separate set of intercostal muscles, which leads to a further decrease in the thoracic volume. When specific abdominal muscles contract, the increased intra-abdominal pressure pushes the diaphragm further into the thoracic cavity, leading to decreased thoracic volumes.[10][11][12][13]

Related Testing

Elevated TPP is a risk factor for ventilator-induced lung injury. For that reason, TPP measurements sometimes guide positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) titration in mechanically ventilated patients, often in those suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). However, there are no data to suggest that routine use of esophageal manometry is required to optimize ventilator settings and decrease ventilator-associated lung injury in patients with ARDS, although it can be useful in complex situations to differentiate between lung and chest wall mechanics.[2] Therefore, measurement of pleural pressure can help to measure the degree of spontaneous breathing effort.[14]

An esophageal catheter with an esophageal balloon can measure esophageal pressure, which is a surrogate for intrapleural pressure due to its location. Since TPP is the alveolar pressure minus the intrapleural pressure, TPP can be calculated relatively easily on mechanically ventilated patients.[15][3]

Pathophysiology

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and neonatal ARDS

ARDS is a lung injury due to acute inflammation that leads to increased vascular permeability. According to the Berlin definition, the onset of respiratory distress and hypoxia should be within one week of a known clinical insult or new or worsening symptoms. Chest imaging should reveal bilateral opacities, and pulmonary edema should not be from heart failure or due to fluid overload.[16] Determining the severity of ARDS is possible by calculating the PaO2/FiO2 ratio.[16]

Neonatal ARDS is an acute pulmonary inflammatory disease resulting from the deficiency of pulmonary surfactant. Although there is no particular treatment, supportive measures such as ventilatory support, surfactant replacement, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), nutritional support, and liquid management are the cornerstones of management.[17]

While the pathogenesis of these two conditions differs, the pathophysiological result and concepts are very similar. There is a loss of surfactant, which causes an imposing increase in alveolar surface tension, pressure, and resistance, which prevent lung expansion. As a result of an increase in alveolar pressure within the lung due to either fluid accumulation or inflammation, there becomes a net increase in transpulmonary pressure, which prevents airflow and lung expansion during inspiration.

Clinical Significance

In the case of pneumothorax, either due to trauma or rupture of blebs, the intrapleural pressure equalizes with the atmosphere and goes from -4 mmHg to 0 mmHg. The TPP is abolished, as alveolar pressure (0 mmHg) minus intrapleural pressure (0 mmHg) equals 0 mmHg. As mentioned above, TPP is the pressure difference holding the lungs open. When TPP is eliminated, the lung collapses. Since the intrapleural pressure is 0 mmHg, the CWP is also eliminated, and the chest wall recoils outward. In respiratory distress syndrome of the newborn, prematurity leads to inadequate surfactant production and therefore increased alveolar surface tension, alveolar collapse, and decreased lung compliance. As a result, breathing is strenuous for the neonate and can lead to respiratory failure and death. As per the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, to prevent such cases, a course of glucocorticoids should be administered to women between 24 and 34 weeks of gestation who are at risk of delivery within seven days. Acutely, mechanical ventilation and administration of surfactant may be necessary.[18][19][20][3]

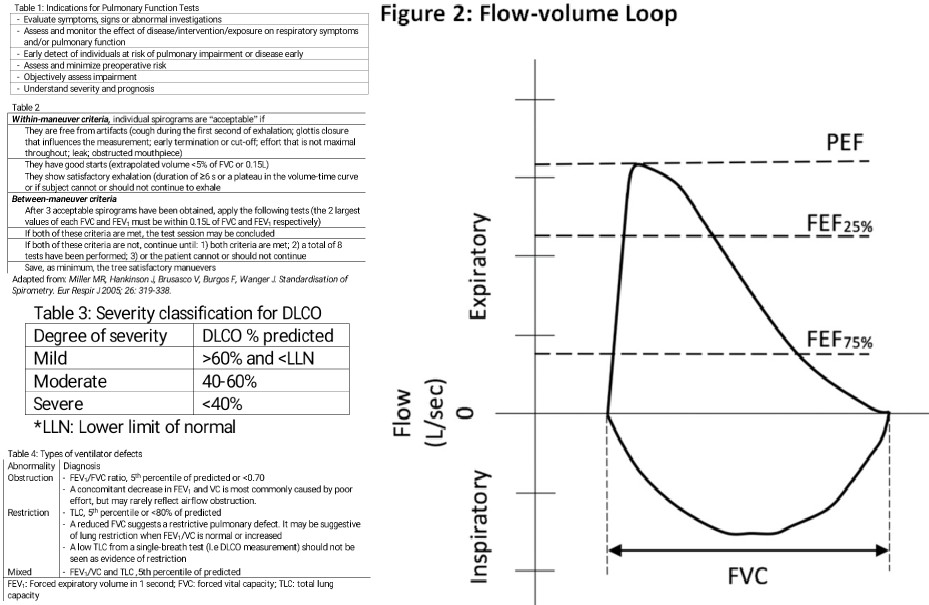

In the case of a pleural effusion, fluid accumulation in the pleural cavity leads to an increase in intrapleural pressure as excess fluid limits inspiration. Inspiration becomes more difficult as the lungs must overcome the increase in intrapleural pressure and resistance to expansion. In cases of obstructive lung disease, such as emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and asthma, there is air trapping, which leads to difficulty in expiring air. During forced expiration, the intrapleural pressure becomes positive, resulting in airway compression and further worsening the air trapping. As air accumulates within the lung due to airway obstruction, lung compliance increases to accommodate the increase in air volume. However, due to airway obstruction, the alveolar pressure remains the same, therefore decreasing the transpulmonary pressure gradient causing lung expansion and air retention. On spirometry, this is evidenced by decreased FVC, decreased FEV1, decreased FEV1/FVC, and an increased functional residual capacity.[21][22][23]

In cases of restrictive lung disease, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or infiltrative lung diseases, increased effort is necessary for lung expansion due to pathologic lung remodeling. The decrease in lung compliance leads to an overall reduction in lung volumes. For these reasons, transpulmonary pressure becomes increased. On spirometry, this shows as decreased lung compliance, decrease in all lung volumes, including functional residual capacity. Since the reduction of FVC is more significant than the decline in FEV1, the overall FEV1/FVC ratio increases in this setting.[14][24]