Continuing Education Activity

Subluxation is an essential entity of traumatic subaxial cervical spinal injuries. There is a varying degree of slippage of the body of one vertebra relative to the adjacent vertebra, owing to ligamentous injury and the jumped facets, with, therefore, a high predisposition for injury to the spinal cord. Road traffic accidents have been mostly implicated in the majority of cases of cervical subluxations. One study found motor vehicle collisions accountable in 51% of such cases, followed by fall-related injuries in 41% of this cohort. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of the traumatic subluxations of the cervical spine and highlights the role of the healthcare team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of traumatic subluxations of the cervical spine.

- Review the appropriate evaluation of subluxations of the cervical spine.

- Outline the treatment options available for the traumatic subluxations of the cervical spine.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the traumatic subluxations of the cervical spine and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) accounts for multispectral neurological deficits and severely affects the dichotomous utilization of health resources, especially in low and middle-income nations.[1]

Nearly 80% of the victims are males, with almost 60% falling within the age group of 16 to 30 years. Moreover, as many as 60% of them are left unemployed following the incidents.[1]

Subluxation is an important entity of traumatic subaxial cervical spinal injuries. There is a varying degree of slippage of the body of one vertebra relative to the adjacent vertebra, owing to ligamentous injury and the jumped facets, with, therefore, a high predisposition for injury to the spinal cord.

Etiology

Road traffic accidents have been implicated in the majority of cases of cervical subluxations.[2] One study found motor vehicle collisions accounted for 51% of such injuries, followed by fall-related injuries in 41% of this cohort.[1]

Acceleration/deceleration injuries and the direct impact on the neck account for such subluxation.[3]

Epidemiology

Traumatic subluxations accounted for 73/163 (44.78%) of all cervical spinal injuries in a single tertiary care center. Most of these patients had Meyerding Type 1 subluxation (35.6%) and presented with the neurological status of the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) 'D' category. The most common location for the subluxation was at the C4/5 (28.76%) level.[1]

Pathophysiology

The interplay of various dynamic movements can lead to multispectral patterns of associated injuries in conjunction with cervical subluxations. The Allen and Ferguson classification system has categorized the principle loading forces with the resultant spinal injuries as follows:

- Hyperflexion injury - unilateral or bilateral locked facets with associated injury to the interspinous ligaments, and teardrop fracture

- Hyperextension injury - fracture of the facets, lamina, and posterior subluxation following disruption of the anterior longitudinal ligament

- Axial loading - leads to burst fracture and damage to all ligaments.[4]

The principal mechanics behind the bilateral jumped facets include hyperflexion injury, axial loading, and anterior shear.[5]

History and Physical

The management of such patients begins with assessing the airway, breathing, and circulation.

The patient's neck should be immobilized with a hard collar to prevent further neurological deterioration from inadvertent neck movements during evaluation and transport.[6]

The primary and secondary survey needs to take place to rule out potential evidence of polytrauma.

The neurological assessment of the patient needs to be done and documented as per the ASIA grading.[7] A quick localization of the lesion is necessary by assessing the pattern of motor weaknesses (quadriparesis vs. quadriplegic vs. central cord syndrome), level of motor weakness (C5- shoulder shrugging, C6- elbow flexion, C7- elbow extension, T1-hand grip), level of areflexia (at the level of injury), single breath count in the patient (phrenic nerve involvement at C3-4-5 level), and the presence of concurrent Horner syndrome (C7-T1).

Evaluation

After hemodynamic stabilization of the patient, the level, pattern, grade, associated bony ligamentous and vascular injuries, and the pattern of cervical cord injuries require evaluation through a series of radiological imaging. The algorithmic approach to be taken for the radiological assessment of the injury is as follows:

- Plain-film X-ray of the spine: this helps in diagnosing, localizing the level of injury, and also to ruling out other traumatic associated bony lesions such as chance fracture, vertebral body, and spinous process fractures. It is of prime help in managing patients in rural areas to correctly manage and transfer them to the tertiary spine center for the needful management of such patients. The dynamic X-ray is of prime importance to rule out subtle instability, particularly in grade 1 subluxation, that a clinician can easily overlook on standard X-rays.

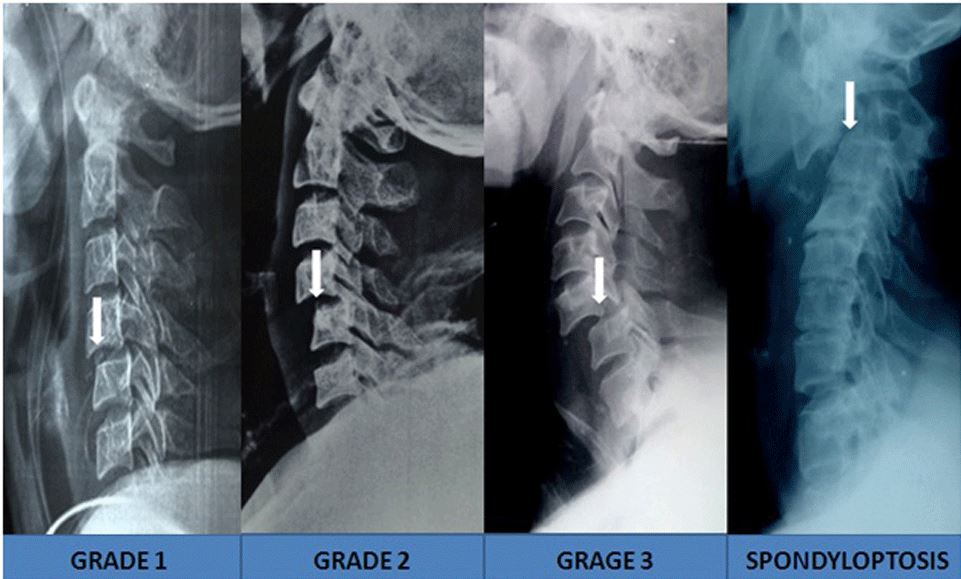

- Computed tomogram (CT) spine- provides bony anatomic details. It is also helpful in diagnosing unilateral or locked facets, concurrent injury to the foramen transversarium (risk of vertebral artery injury), validating the integrity of the lateral mass, and the lamina (for screw fixation of appropriate length from the posterior approach). The Meyerding scoring system applies for grading the subluxation (Grade I -translation up to 25%, grade II up to 50%, grade III up to 75%, grade IV up to 100%, and grade V complete ptosis of one vertebral body over another).[8]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine- provides details on the pattern of soft tissue injury (ligaments) and damage to the spinal cord (compression, transection, central cord syndrome). The use of tractography can also be applied to assess the integrity of the nerve for tracts to predict the neurological recovery in the patients. A traumatic syrinx may develop in a few patients with initially missed grade 1 traumatic subluxations.[3]

- Vertebral artery angiography: this modality is of prime importance, especially in patients with the extension of the fracture to the foramen transversarium and in patients with high grades of subluxation at C2-C6 levels. There may sometimes be concurrent dissection or occlusion of the vertebral artery as well.[1][6]

The locked facets will show specific findings in radio imaging. The overlap of more than 50% between the articulating surface of the facet joints is considered unstable.[6] The 'bow-tie' sign or the 'batwing' sign is characteristic of a unilateral jumped facet joint.[9] The CT scan shows a reverse hamburger bun sign highly indicative of a facet dislocation.[10]

Various scoring systems have been developed to classify patients with cervical spine injuries. The subaxial cervical spine injury classification system encompasses the following:

- Injury morphology - compression, distraction, and translational patterns

- Status of the disco-ligamentous complex

- Neurological status of the patient[11]

The AO Spine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system, on the other hand, categorizes injury depending on the following:

- Injury morphology- compression injury (A), posterior tension band injury (B), translational injury (C), which further subdivide into four subtypes

- Facet injury - divided into four subtypes

- Neurological status of the patient

- Case-specific modifiers - constituting the central disc, metabolic bone diseases, and vertebral artery injury.[12]

The AO Spine classification system seems to be of paramount importance in managing patients with traumatic subluxations owing to its importance to the status of the facet joints, the pivotal factor determining spinal stability. Damage to the facet joints, therefore, provides a strong rationale for undertaking global fixation of the traumatic spine in neurologically preserved patients.[12]

Treatment / Management

Regarding the flexion-distraction pattern of injury that plays a central role in traumatic subluxations, the injuries categorize based on the severity of the injury :

- Facet subluxation

- Unilateral facet dislocation/ facet fracture and dislocation

- Bilateral facet dislocations.[13]

The nondisplaced facet fracture or minimal diastasis of < 1 mm can be managed with an orthosis. However, facet displacement and concurrent ligamentous injury warrant surgical fixation.[13]

The initial aspects of handling these cases deal with the judicious application of cervical traction that helps in the following:

- Stabilization of the spine and

- Reduction of the grade of the subluxation in cases of reducible locked facet joints

Care always needs to avoid cord traction due to heavy tractional weights.[1]

In cases with locked facets, the clinician should attempt a closed reduction under anesthesia, which is successful in almost 95% of cases.[14]

If there is no reduction and the preoperative MR images show the presence of disc prolapse, an anterior approach is the next step, with discectomy followed by open reduction with the aid of a Casper distractor. The reduction can then take place by anterior-only fusion. The failure of reduction needs the posterior reduction of the jumped facets, followed by 360-degree global fixations in neurologically preserved patients.[14]

The surgical plan in the management of the patient then varies according to the Meyerding grading system, the ASIA neurological status, and the relevant scoring system of the patient.[1][12] The treatment algorithm is also determined by the patient's characteristics as well as the expertise of the team. The anterior approach is better suited to deal with the herniated disc, whereas the posterior approach helps restore the posterior tension band.[13]

If there is a good reduction following traction, the patients can receive an anterior approach with discectomy or median corpectomy followed by in-situ bony graft fusion or the usage of allograft spacers aided with plate and screw fixations.[1][13]

Sometimes, owing to financial barriers, simple graft placement can also be undertaken. In cases of failed reduction from traction, the clinician can attempt reduction following muscle relaxation after induction of anesthesia. If reduction fails in patients with ASIA 'A' and 'B' status, posterior-only fixation by interspinous wiring is justified for anatomical fixation to aid in early rehabilitation.[1] However, in patients with ASIA 'C' and 'D' status, the posterior approach is necessary to first to unlocking the jammed facet, and the anatomical fixation is carried out following lateral mass and translaminar screw and rod fixation.[1] This approach can be reinforced with fixation from the anterior approach as well. However, in neurologically stable patients, if there is significant disc prolapse, discectomy, or corpectomy is carried out (to prevent cord injury when the patient is in the prone position), then the posterior approach to unlock the facets and posterior instrumentation is the appropriate procedure, followed again by the anterior approach to bony graft placement along with plate and screw fixation (360-degrees approach) is warranted.[15]

With regards to the AO Spine scale system, the recommended plan of management includes the following:

- A0 - conservative

- A1 - conservative, if kyphosis >15 degrees- anterior mono-segmental fusion

- A2 - conservative, if kyphosis >15 degrees- anterior bi-segmental fusion

- A3 - anterior fusion mono/bisegmental fusion

- A4 - anterior bisegmental fusion

- B1 - posterior bisegmental

- B2 - approach and fusion length depend on the A component

- B3 - anterior mono segment, in ankylosis spondylitis- posterior long segment fixation

- C1 - approach and fusion length depend on the A component

- F1 - conservative

- F2 - approach depends on the B and C components

- F3 - approach depends on the B and C components

- F4 - approach depends on the B and C components.[13]

The asymptomatic vertebral artery injury has not been shown to hinder the operative management of the subluxations. The use of aspirin is recommended in the postoperative period. There is still no consensus for managing symptomatic vertebral artery injuries associated with traumatic cervical spine subluxations.[13][14]

Differential Diagnosis

Pseudo-subluxation associated with an absent cervical pedicle.[16]

Prognosis

The subluxation of the cervical spine and the associated complications can negatively impact patients’ functionality and quality of life.[17] Most patients with poor neurological status depend on their care providers, even for their activities of daily living.

There is a high risk of the need for repeated admissions owing to varied complications in these cohort groups, and it has been shown to be as high as 27.5% in one study.[18]

Hospital-acquired pneumonia and pressure ulcers harbinger disability and lurk mortality, most often in subsets of patients with ASIA grades of A, B, and C.[19]

Complications

The complications can be categorized as follows:

- Neurological - quadriplegic, quadriparesis, central cord syndrome, and cruciate paralysis

- Phrenic nerve injury (C3-5 level)

- Vertebral artery injury (C2-6 level)

- Spinal cord injury-compression, transection, contusion, and traumatic syrinx

- Early complications of the surgery - hematoma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, injury to a vertebral artery hematoma (especially in lateral mass fixation), graft extrusion, cord edema, and cord herniation

- Late complications of surgery - surgical site infection, tracheo-oesophageal fistula, implant failure, adjacent segment disease, kyphotic deformity, and nonunion

- Secondary complications relating to spinal cord injuries - such as pneumonia, pressure ulcers, deep vein thrombosis, urinary tract infections, muscle atrophy, and spasticity

- Collateral impact on the care providers - heighten the caretaker burden scale in multispectral patterns (physical, economic, social, and emotional aspects).[1][2]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

There need to be provisions for the following:

- Early anatomic stabilization.

- Focusing on preserving the functionality of the cord.

- Early mobilization and staged physiotherapy programs.

- The institution of the patient care bundle approach in preventing secondary complications in the patient

- Opt for surviving, reviving, and then eventually thriving of such patients.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The pivotal basis in managing patients with traumatic subluxation is three-fold:

- Early reduction, spinal decompression and graft, and implant fixation

- Early institution of graded physiotherapy to maximize neurological recovery

- Prevention of secondary complications in the patients

However, in patients with severe deficits, the caretakers have to look after them even for their activities of daily living. The management plan should, therefore, be targeted, focusing on the patient and the care provider together as a unit.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

No significant differences were observed between approaches taken for the anatomical stabilization (anterior-only, posterior-only, and 360 degrees) with the pattern of ASIA recovery seen among the patients.[2]

The prime goals in managing these patients are early anatomical fixation with spinal decompression, followed by the strategies to survive, revive, and thrive in these cohorts of patients through:

- Specific care bundle approaches in minimizing secondary complications and

- Swift implementation of the strategic long-term rehabilitative processes

Diagnosis and management of these injuries require the efforts of an interprofessional healthcare team that includes clinicians, specialists (orthopedic and/or neurologic), nurses, and physical therapists. Clinicians must obtain an appropriate specialist referral when these patients present. Many of these patients will first be seen in the ED. Nurses can assist with evaluation, follow-up monitoring, assisting during surgery, and administering pain medication. Physical therapists will play a critical role in both non-surgical and post-surgical cases. Open communication channels between all team members are crucial to implementing a coordinated team effort. This interprofessional approach will yield optimal patient results. [Level 5]