Continuing Education Activity

Parkinson disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that mostly presents in later life with generalized slowing of movements (bradykinesia) and at least one other symptom of resting tremor or rigidity. Other associated features are a loss of smell, sleep dysfunction, mood disorders, excess salivation, constipation, and excessive periodic limb movements in sleep. This activity reviews the pathophysiology, presentation, and diagnosis of Parkinson disease and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Describe the pathophysiology of Parkinson disease.

Review the presentation of a patient with Parkinson disease.

Outline the treatment and management options available for Parkinson disease.

Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and outcomes in patients with Parkinson disease.

Introduction

Parkinson disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that mostly presents in later life with generalized slowing of movements (bradykinesia) and at least one other symptom of resting tremor or rigidity. Other associated features are a loss of smell, sleep dysfunction, mood disorders, excess salivation, constipation, and excessive periodic limb movements in sleep (REM behavior disorder).[1][2][3]

It is estimated that Parkinson disease affects at least 1% of the population over the age of 60. The disorder is associated with the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and the presence of Lewy bodies. Most cases are idiopathic. Only about 10% of cases have a genetic cause, and these cases are seen in young people.

The disorder has a slow onset but is progressive. Tremor is often the first symptom and later can be associated with bradykinesia and rigidity. Postural instability is usually seen late in the disease and can seriously impact the quality of life. Also important is the presence of autonomic symptoms that may precede the motor symptoms in some patients. The diagnosis in most patients is based on history and clinical presentation. SPECT scans can be performed in doubtful cases or to rule out other neurological disorders.

Etiology

Over the past century, our understanding of the etiology of PD has evolved immensely. In 1919, it was first recognized that loss of pigmentation in the substantia nigra of the midbrain is a feature of the post-mortem brain examination of patients with PD. In the 1950s, it was further understood that the pigmented neurons that are lost in the substantia nigra are dopaminergic, and it is the loss of dopamine in subcortical motor circuitry that is implicated in the mechanism of the movement disorder in PD.[4][5]

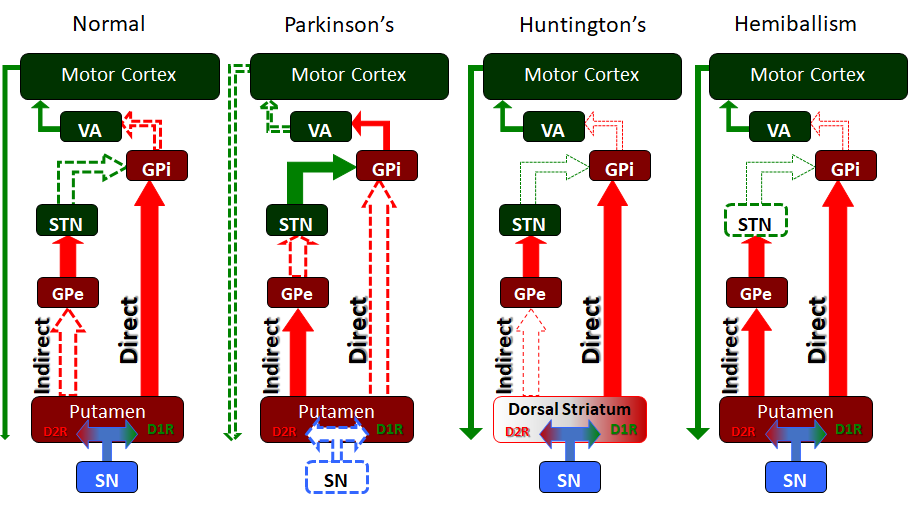

PD is a disorder of the basal ganglia, which is composed of many other nuclei. The striatum receives excitatory and inhibitory input from several parts of the cortex. The key pathology is the loss of dopaminergic neurons that lead to the symptoms.

The cause of PD has been linked to the use of pesticides, herbicides and proximity to industrial plants. Some individuals have been found to develop Parkinsonian-like features after injection of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). This chemical accumulates in the mitochondria. There is also research suggesting that oxidation and generation of free radicals may be the cause of damage to the thalamic nuclei.

Genes are important as the risk of PD in siblings is increased if one member of the family has the disorder. These cases also tend to occur much earlier in life.

Abnormal levels of aggregated alpha-synuclein are a major component of Lewy bodies and are found at autopsy. It is felt that the altered function of alpha-synuclein may play a role in the etiology of PD. Current research is focused on preventing the propagation and aggregation of alpha-synuclein.

Epidemiology

PD affects 1 to 2 people per 1000 at any time; the prevalence increases with age to affect 1% of the population above 60 years. 5% to 10% of patients have a genetic predisposition. The incidence and prevalence of PD do increase with advancing age; the condition is more common in men than women.

Pathophysiology

In 1999, several members of an Italian family in the New Jersey area were identified as having PD, and the search for the genetic basis of this illness gained momentum. Studies on families with the rare autosomal dominant form of this disease led to a further breakthrough. The primary etiology appears to be the accumulation of alpha-synuclein in various parts of the brain, primarily the substantia nigra, leading to degeneration and subsequent loss of dopamine in the basal ganglia that control muscle tone and movement. The accumulation of the alpha-synuclein protein may be secondary to a genetic predisposition, such as with the PARK-1 mutation identified in the Contursi kindred of New Jersey or triggered by an unknown environmental agent. There has been some recent interest in establishing an infectious etiology that triggers this alpha-synuclein accumulation after reports that the earliest degenerative change in PD appears in the myenteric plexus on the GIT, from where it progresses up to involve the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, the sleep centers in the pons, and then the midbrain. This interesting theory also addresses why patients with PD typically suffer from gastrointestinal motility issues and REM sleep disorder, both of which can precede the motor manifestations of PD for many years.

Therefore, as our knowledge about the etiology of PD evolves, it is not enough to regard this disorder as primarily caused by a lack of dopamine in the substantia nigra. There appears to be a darker, more extensive pathophysiology behind this, and the non-genetic causes of alpha-synuclein deposition in the brain are a subject of active research.[6]

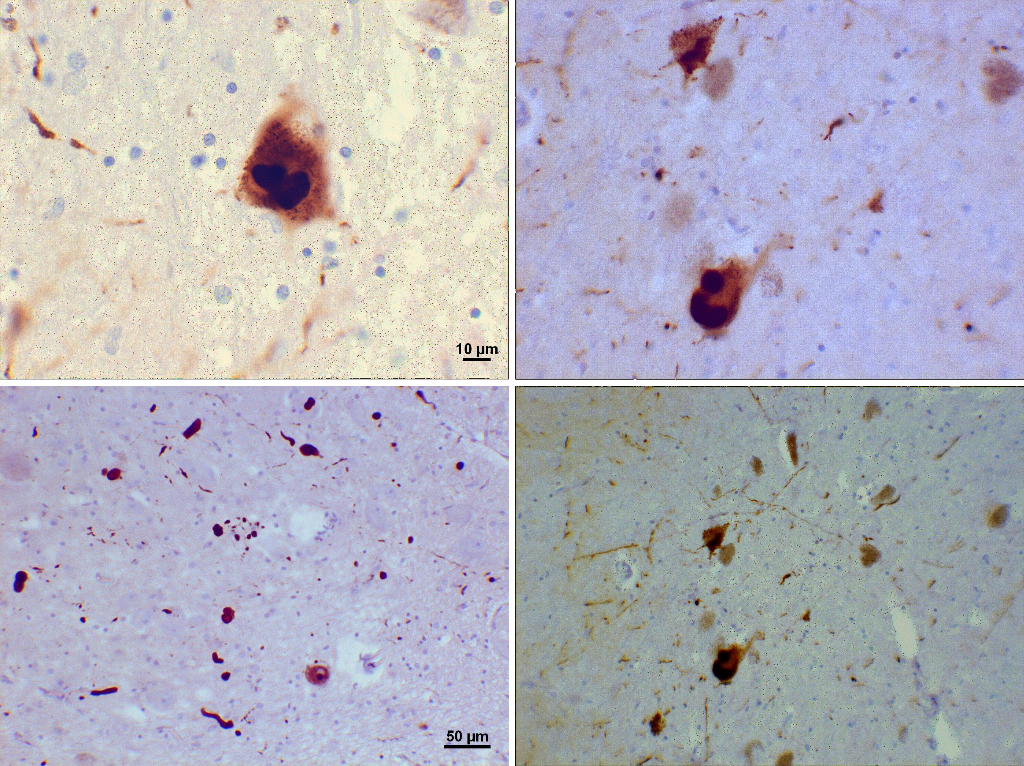

Histopathology

Loss of dopamine pigment in the substantia nigra is visible to the naked eye in cases of PD.

Histologically, PD is characterized by neuronal inclusions of alpha-synuclein in neuronal cell bodies (Lewy bodies) and within neuronal cell processes (Lewy neurites). The combination of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites is sometimes referred to as Lewy-related pathology. The hallmark of any neurodegenerative disease is selective neuronal loss, and loss in PD is most marked in the substantia nigra pars compacta. It has been known for many years, however, that Lewy bodies in PD extend well beyond the substantia nigra. Based on the distribution of alpha-synuclein pathology, Braak and coworkers have proposed a staging scheme for PD. In this scheme, neuronal pathology occurs early in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in the medulla and the anterior olfactory nucleus in the olfactory bulb. As the disease progresses, locus ceruleus neurons in the pons and then dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra are affected. Pathology extends to the basal forebrain, amygdala, and medial temporal lobe structures in later stages, with convexity cortical areas affected in the last stages. Subsequently, there have been proposals that autonomic neurons in the peripheral nervous system may be affected by the involvement of the central nervous system (CNS), which has prompted recognition that PD is a multiorgan disease process, not merely a disorder of the CNS. Moreover, it has fed the debate on cell-to-cell transmission of unknown transmissible agents from the gut to the brain through retrograde transmission in the vagus nerve.

History and Physical

An earlier feature of PD is tremor, typically unilateral and present at rest, which is usually the reason for seeking help at a neurology clinic. After using the hands, such as to pick up a book, the tremor may vanish for some minutes, only to return when the patient is distracted and resting once again. This is the so-called reemerging tremor that is typical of PD.

Although tremor is a prominent and early symptom of PD, it is not always present and is not a necessary feature for diagnosis.

Slowness, or bradykinesia, on the other hand, is a core feature of PD. Patients will notice it takes them longer to do simple tasks, their walking is slower, and their ability to respond to threats is compromised. In the clinic, patients demonstrate an inability to tap their index finger and thumb rapidly, tap their foot rhythmically on the floor, or walk steadily.

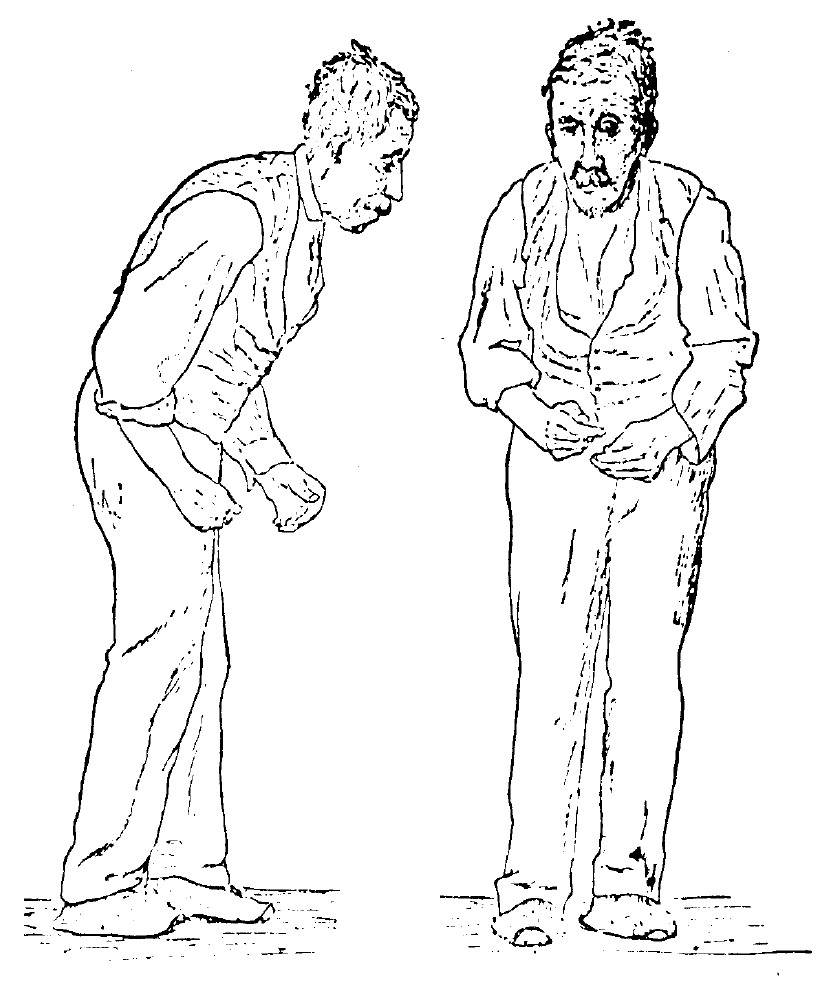

Rigidity is the third prominent feature of the examination. Patients appear stiff and find it difficult to rise out of a chair without support. While walking, there is reduced arm swing, more so on one side than the other, as PD typically is asymmetric at the onset. Checking muscle tone, lead pipe, and cogwheel rigidity can be appreciated.

A combination of bradykinesia and rigidity leads to some other characteristic features of PD, such as micrographia. Interestingly, the diminishing size of Hitler’s handwriting over time leads to a retrospective diagnosis that he may have suffered from PD.

The fourth prominent feature of PD is gait disturbance, although this is typically a late manifestation. Flexed posture, reduced arm swing, festination, march-a-petits- pas, camptocormia, retropulsion, and turning en bloc are popular terms to describe the gait in PD. In advanced PD, patients will have trouble rising from a chair without support, they take small, slow steps, they are unable to stop themselves from falling if pushed lightly, they cannot turn around without taking several small steps, and they tend to freeze when faced with certain stimuli such as a doorframe or a passer-by. With experience, a neurologist can diagnose a long-suffering PD patient from their progress to the office chair from the waiting room. However, it has to be said that some other neurologic conditions, such as normal pressure hydrocephalus, can produce a similar gait. Gait disorder is not an early feature of PD but is frequently described as it is easy to recognize and cinches the diagnosis in later stages.

Apart from the above four prominent features of PD in the clinic, patients are usually asked about constipation, drooling, mood disorder and depression, REM sleep disorder, and anosmia. These subtle symptoms frequently accompany the tremor/rigidity paradox of patients with PD and reflect the underlying alpha-synuclein deposition-mediated neurodegeneration in parts of the brain other than the substantia nigra.

Autonomic symptoms are common in PD. Besides orthostatic hypotension, constipation, difficulty swallowing, urinary retention, and erectile dysfunction are common. Often, these symptoms do not improve with treatment.

Depression is also very common in PD. As the disease progresses, dementia with significant loss of cognitive function is common.

Evaluation

Evaluation of patients with PD usually starts with the history and physical examination geared to picking up the signs described above. Movement disorders clinics may employ the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale to quantify patient mentation, behavior, mood, activities of daily living, tremors, motor examination, and complications of therapy.[7][8][9]

There is no specific laboratory or imaging study that can help make a diagnosis of PD.

An essential part of the evaluation of PD is to exclude the effect of medications that can lead to extrapyramidal side effects and motor manifestations that are, at times, indistinguishable from classical PD. Typically, it is the traditional antipsychotics that are implied. In these cases, the nonmotor manifestations of PD, such as anosmia, are not found.

It is also important to exclude other neurodegenerative conditions. Other alpha-synucleinopathies, such as Lewy body disease and multiple system atrophy, can present with PD but have subtle differences that distinguish them as separate disease entities. Similarly, tauopathies such as progressive supranuclear palsy can present with bradykinesia, rigidity, and gait disturbance.

For example, all the diseases below may have the same motor manifestations of PD, but:

- Progressive supranuclear palsy patients will have vertical gaze paralysis on examination.

- Lewy body dementia will have the added features of onset with dementia and hallucinations.

- Multisystem atrophy will present with early-onset autonomic dysfunction and pyramidal and cerebellar signs.

In terms of investigations, PD remains one of the few medical conditions where clinical examination remains sufficient for a formal diagnosis. MRI is useful in narrowing the differential and excluding other conditions that may present with a similar examination, such as normal pressure hydrocephalus or subcortical stroke. In certain situations, a DAT scan may be used to identify the loss of dopaminergic uptake in the basal ganglia. However, the interpretation of this test can be challenging, and the routine use of this test is to be discouraged.

Practically, one of the best ways of establishing a diagnosis of PD in a patient with suggestive symptoms is a clear response to Levodopa treatment. This is either short-lived or not well seen with overlapping syndromes.[8][10][11]

It is important to be aware that there is a high rate of diagnostic errors between PD and essential tremor in the community.

Imaging studies are useful to exclude bleeding, stroke, hydrocephalus, mass lesions, and Wilson disease. Lumbar puncture is done to exclude normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Treatment / Management

Pharmacologically, this is typically levodopa (combined with Carbidopa, which decreases side effects and improves CNS bioavailability). A dopamine agonist (Pramipexole, Ropinirole) may be started in younger patients; it may not be as effective as levodopa but will have fewer side effects. Anticholinergics or Amantadine may be used if the predominant symptom to be controlled is a tremor.

Selegiline is often used to treat early disease and can provide mild symptom relief.

Most antiparkinsonian medications provide good symptom control for 3 to 6 years. After this period, the disease progresses and is often unresponsive to medications. In general, younger patients should be treated more aggressively than older people.

A multidisciplinary approach to the management of PD is essential. Patients do much better when a structured physical therapy program geared to PD is employed; they can be taught to improve their balance and gait, improve their stability, and maintain an active life. Some unique features of this movement disorder have been exploited to advantage; patients do well with music therapy in physical fitness programs, cycling, and boxing. Patients who cannot walk may find themselves able to dance. Depression, carer fatigue, constipation, REM sleep disorder, paranoia, and psychosis are often seen. They can be side effects of the medication or part of the primary disease, and all need to be addressed.

Patients responding well to pharmacological treatment may grow resistant with time, develop abruptly on/off motor symptoms, or suffer from disabling dyskinesia as a side effect. Varying the pharmacokinetics of levodopa has sometimes helped, such as newer formulations of delayed-release levodopa or a continuous GI pump infusion form of levodopa. The addition of other medications and balancing the timing of the medication can have a huge effect on the patient.

For some patients who do not respond to all measures, deep brain stimulation techniques are increasingly available to stabilize the balance of excitatory and inhibitory signals to the subthalamic nucleus or the globus pallidus. Although not entirely understood why this has such a positive effect on treatment failures in PD, it is new hope for advanced patients with PD and an area of active progress.[12][13][14]

The nonmotor symptoms like psychiatric, autonomic, and sensory are much harder to manage. Simply adding more medications to the patient's regimen is not the answer because of potential adverse reactions and drug-drug reactions. Current recommendations include:

- Sildenafil to treat erectile dysfunction

- Modafinil for day time somnolence

- Polyethylene glycol for constipation

- Levodopa for period limb movements during sleep

- Methylphenidate for fatigue

- Dementia is managed with cholinesterase inhibitors

- Depression is managed with SSRIs

- Psychotic symptoms are managed with antipsychotics and pimavanserin.

- Anxiety is managed with SSRIs

- Impulse behaviors are managed by cognitive behavior therapy

Deep brain stimulation has become the surgical procedure of choice as it does not damage brain tissue, is reversible, and the stimulation can be altered as the disease progresses. DBS involves stimulation of the STN, globus pallidus interna, and the thalamus. However, DBS is not complication-free; it is prohibitively expensive, and its long-term benefits remain debatable.

More evidence indicates that exercise can help improve gait, balance, and flexibility. Unfortunately, the benefits of exercise are not sustained; the risk of falls is very high.

Speech therapy may help some patients.

Differential Diagnosis

- Essential tremor

- Huntington chorea

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Progressive supranuclear palsy

- Neuroacanthocytosis

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus

Prognosis

The rate of progression of the disease may be predicted based on the following:

- Males who have postural instability of difficulty with gait.

- Patients with older age at onset, dementia, and failure to respond to traditional dopaminergic medications tend to have early admission to nursing homes and diminished survival.

- Individuals with just tremors at the initial presentation tend to have a protracted benign course.

- Individuals diagnosed with the disease at an older age combined with hypokinesia/rigidity tend to have a much more rapid progression of the disease.

The disorder leads to disability of most patients within ten years. The mortality rate of patients with PD is three times the normal population. While treatment can improve symptoms, the quality of life is often poor.

Complications

- Depression

- Dementia

- Laryngeal dysfunction

- Autonomic dysfunction

- Kyphosis leading to cardiopulmonary impairment

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

All patients diagnosed with PD need long-term follow-up because of the progressive behavior and motor abnormalities. Slight adjustments in medications are needed in most patients. In addition, many patients develop erratic behavior like impulsivity, psychosis, paranoia, and somnolence.

Consultations

- Psychiatrist

- Neurosurgeon

- Speech therapist

- Urologist

- Dietitian

- Gastroenterologist

- Otolaryngologist

- Physical therapist

Pearls and Other Issues

Guidelines

- Sildenafil may be prescribed for erectile dysfunction

- Constipation can be managed with polyethylene glycol

- Somnolence can be managed with modafinil

- Methylphenidate for excessive fatigue

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional management

PD is the most common motor disorder in the U.S. The disorder has no cure and is progressive. The condition can present with motor abnormalities and a variety of psychiatric and autonomic problems. Almost every organ is affected by this disorder, and as the disease progresses, management can be difficult. An interprofessional team approach is the best way to manage the disorder.

Besides, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and physical therapists play a vital role in the daily management of these patients. Nurses have many roles when it comes to looking after patients with PD. The first is the education of the patient and family and encouraging them to participate in decisions regarding the treatment. In addition, nurses are often the first to spot difficulties in daily living and, hence, should make the appropriate referrals or recommendations. Nurses also provide psychosocial support and referral to a therapist if required. Finally, the nurse plays a key role in assessing the risk of falls and making referrals to a physical therapist for an ambulatory device. Other issues commonly encountered in these patients that require attention include dysphagia, cognitive decline, depression, and somnolence.

Psychosocial support should be addressed by the social worker and neuroscience and psychiatric nurses. Other issues that need attention include changes in personality, depression, decline in cognition, sleepiness, dysphagia, and impulse control disorders.

Finally, the nurse should provide information on end of life care, financial planning, disability application, and referral to a nursing home.[15][16] [Level 5]

Since most patients with PD are on multiple medications, the pharmacist has to closely monitor the drugs to ensure that they are safe and not causing any adverse reactions and alert the clinician should any concerns arise.

These interprofessional team strategies will lead to better outcomes for PD patients. [Level 5]

Outcomes

PD is a progressive disease with no cure. The lifespan is reduced compared to the general population. However, the rate of disease progression is not always easy to predict. In the later stages of the disease, falls, gait difficulties, and dementia are common. The quality of life for most patients with PD is poor.[17][18][15] [Level 5]