Procedures

Tests performed in patients presenting with epiphora are classified as secretory tests and excretory tests.

Secretory Clinical Tests

Examination of the Tear Film and Cornea

A drop of 2% fluorescein is placed at the lateral canthus, and the patient is asked to blink. With the lids open, there should be a 1-mm tear film along the upper and the lower eyelid margin. A poor tear film may indicate dry eye syndrome (keratitis sicca). Corneal staining may also be examined at this point.

Tear Break-up Time

The patient is asked to blink after the placement of the fluorescein in the eye. Normally, the tear film breaks up after 15 seconds. Anything shorter may indicate a deficiency in the mucus component of the tear film or an excessive aqueous component.

Schirmer Tests

Schirmer's 1 Test

This was first described by Otto Schirmer in 1903.[3] The patient sits upright. A Whatman filter paper is folded at an angle of 90 degrees. The strip is 35 mm by 5 mm. The end is bent at about 5 mm, and this short tail is placed in the inferior fornix between the medial two-thirds and lateral one-third of the lower eyelid. No drops or anesthetic drops are administered. The patient is asked to blink normally in a semi-dark room for five minutes. The distance to which tears have traveled is read from the filter paper. In patients under the age of 40 years, the wetting is more than 15 mm. In patients over the age of 40 years, 10 mm is considered normal. Anything less than 5 mm indicates abnormally low aqueous tear production. This test is called the Schirmer's 1 test. It measures reflex aqueous tear production.

Schirmer's Test with Anesthetic

A drop of topical anesthetic is placed in the fornix, and the eye is wiped after a minute. The filter paper test is now repeated. The measurement under the age of 40 years should be 10 mm or more, and in the older group, it should be at least 5 mm. This indicates the secretion of the accessory lacrimal glands. In inflammatory lacrimal diseases like Sjogren syndrome, dacryoadenitis, and sarcoidosis of the lacrimal gland, these tests will be abnormal.

Schirmer's 2 Test

In this test, the first division of the trigeminal nerve is stimulated with a cotton tip applicator in the nose. The sensory irritation should cause the oversecretion of tears. Most physicians no longer perform this test as it does not add anything useful about the tear production.

Excretory Clinical Tests

The Saccharin Test

A drop of 2% saccharin is placed in the conjunctival fornix. 90% of patients with a patent lacrimal system will taste it in 15 minutes. Some surgeons find this test useful to determine if the patient has epiphora due to increased secretion or decreased drainage.

Fluorescein Dye Disappearance Test

After a drop of 2% fluorescein has been placed in the fornix, the fluorescein remaining in the conjunctival cul-de-sac is examined with the cobalt blue light after five minutes. The amount of remaining fluorescein can be graded using a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates no remaining dye, and 4 indicates all the dye remains. This is also compared to the opposite eye. Retention of the fluorescein indicates a delay in tear flow. If the result is normal, lacrimal drainage dysfunction is unlikely.[4]

The Jones I & II Tests

These tests assess the flow of tears into the lacrimal sac and through the nasolacrimal duct.

The Jones I Test

2% fluorescein dye is instilled in the fornix. The presence of dye in the inferior meatus indicates a positive result of Jones I; the dye presumably flowed from the tear lake to the inferior meatus via a patent lacrimal system. A negative test suggests an obstructed lacrimal system. Dye in the inferior meatus can be demonstrated by the insertion of a swab into the nose, by asking the patient to blow their nose into a tissue, or by asking the patient whether they can taste the dye. Although this is a physiologic test, the Jones I test is rarely used because the false-negative rate is 22%.[5][6] A number of other factors confound this test: if there is poor tear secretion, there is less chance of retrieving the dye in the nose. Gravity and the volume of fluorescein instilled will also affect the passage of the dye.

The Jones II Test

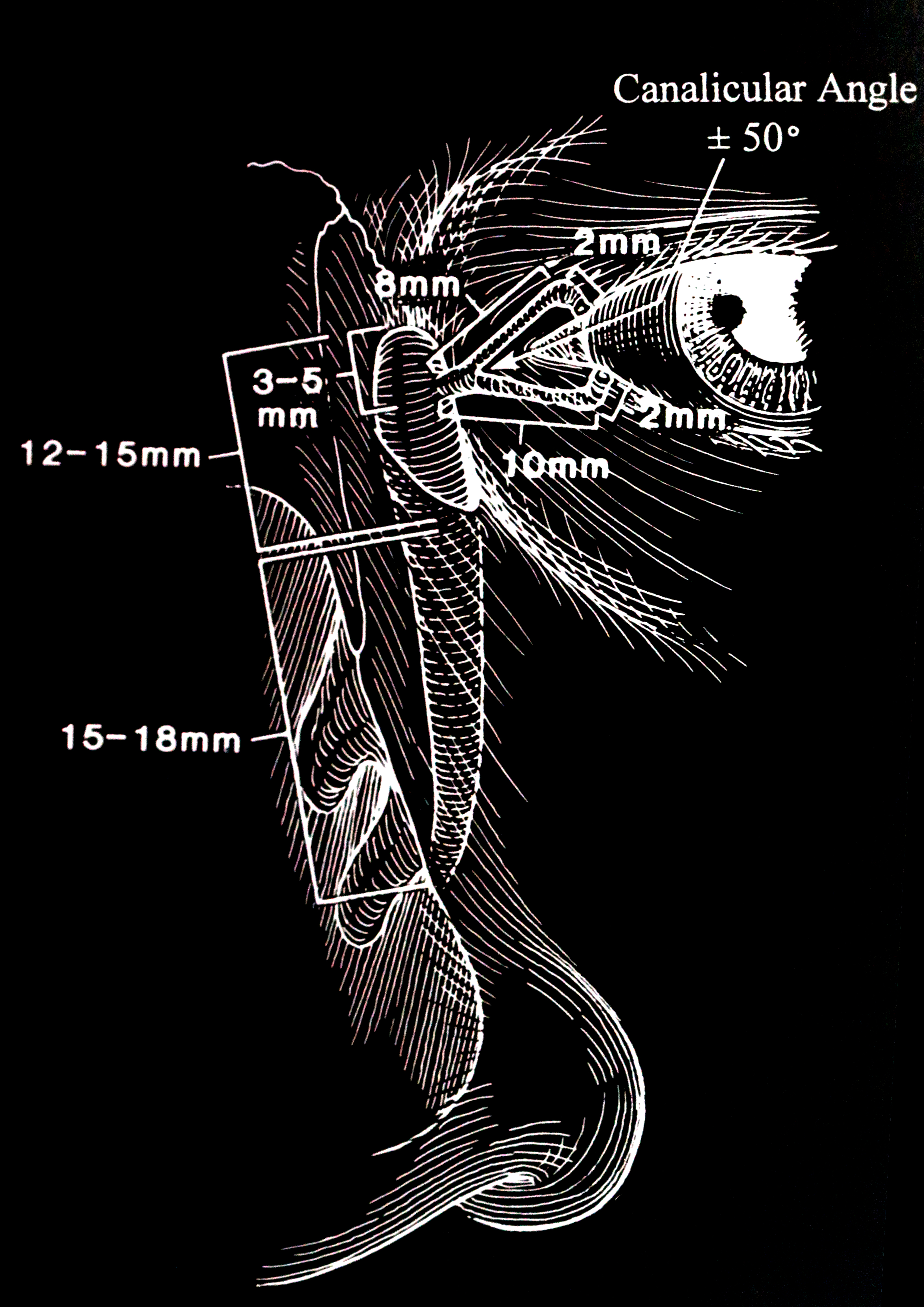

This is a non-physiologic test. After the puncta are soaked with topical anesthetic, the puncta are dilated with a Nettleship dilator, and any stenosis is noted. It is important to explain to the patient that this is an investigative test and not a treatment. Furthermore, the patient must be informed that fluid may be tasted in the nose and throat. The 23-gauge lacrimal irrigating cannula (after it is lubricated with an ointment) is inserted gently while applying lateral traction to the eyelid to keep the canaliculus from kinking. Probing will show any canalicular obstruction or stenosis. A 3-cc syringe is best for irrigating the lacrimal system. Saline is flushed through the punctum once the canaliculus is in the horizontal canaliculus. The degree of force needed or the resistance faced when irrigating is learned by experience. The results are interpreted as follows:

- If there is difficulty advancing the cannula down the canaliculus, a canalicular scar is present.

- If there is a flow of fluid back through the opposite punctum, but there is no evidence of lacrimal sac distension (this is often difficult to determine even with palpation), then a common canalicular scar is likely. However, the obstruction may also be in the lacrimal sac or the nasolacrimal duct.

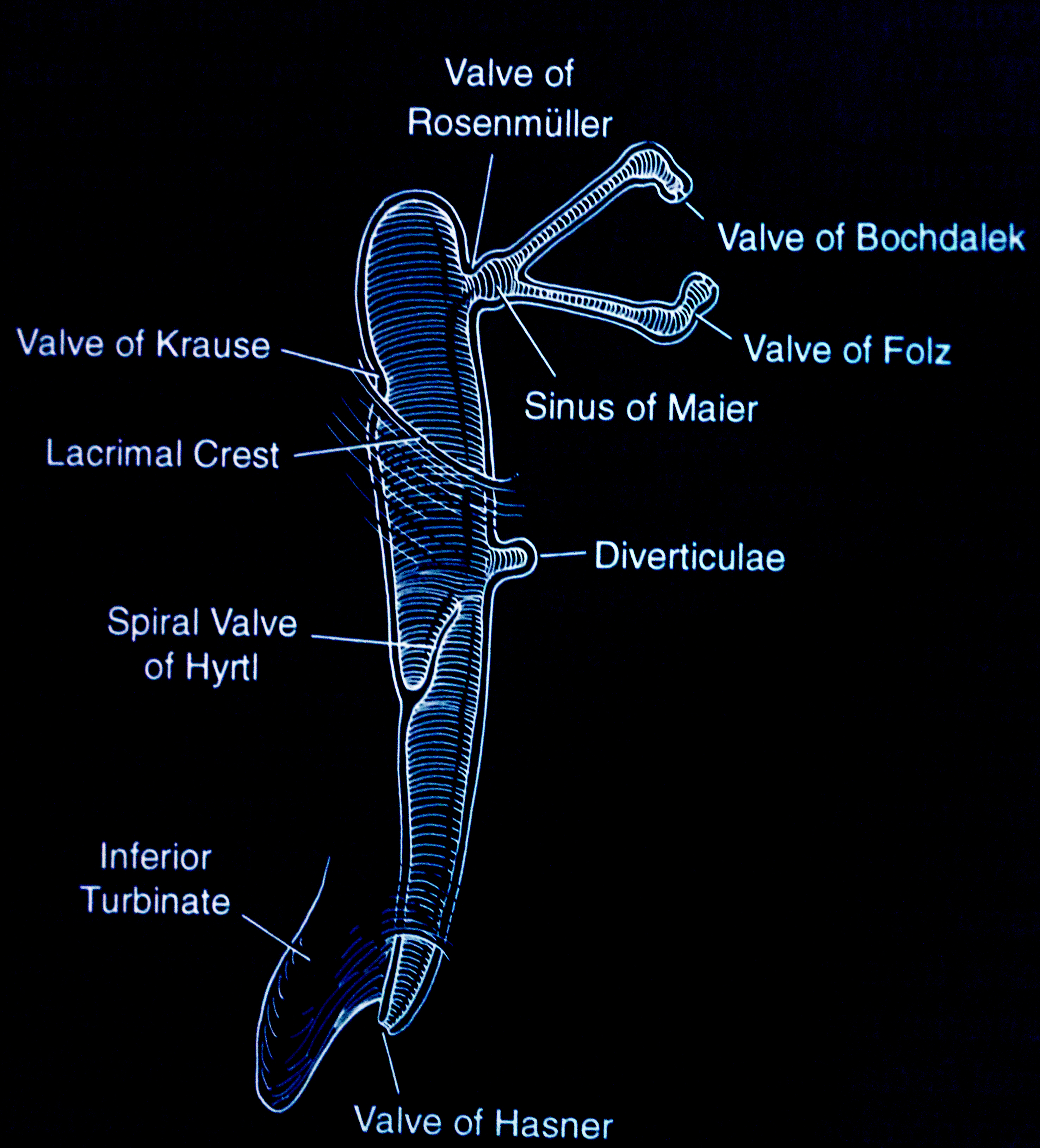

- If there is retrograde flow through the canaliculus and no fluid passes into the nose, it indicates a nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The valve of Rosenmüller prevents the fluid from refluxing through the opposite canaliculus.

- If there is a flow of fluid through the opposite canaliculus and some flow into the nose, partial nasolacrimal duct stenosis may be present.

- If there is a free flow of fluid down the nasolacrimal duct with no resistance and no flow through the opposite canaliculus, it indicates a patent nasolacrimal system. However, the patient may still have a dacryolith in the lacrimal sac and the lacrimal system or a physiologic nasolacrimal system obstruction and still have a free flow of fluid down the nasolacrimal duct. It is important to remember that the degree of force used to irrigate can give confusing results since this is a non-physiologic test.

- Even if a diagnosis of an obstruction in the nasolacrimal duct is made, it is imperative that the lower eyelid, punctum, and lateral canthus are examined in all patients as there may be laxity of the lower eyelid, which may also need to be corrected together with a dacryocystorhinostomy. The laxity of the lower eyelid may be involutional and be an additional cause of epiphora, or the constant wiping may have exacerbated it. On reviewing the last 350 dacryocystorhinostomy procedures on our patients, we found 18% had concurrent lower eyelid laxity corrected.

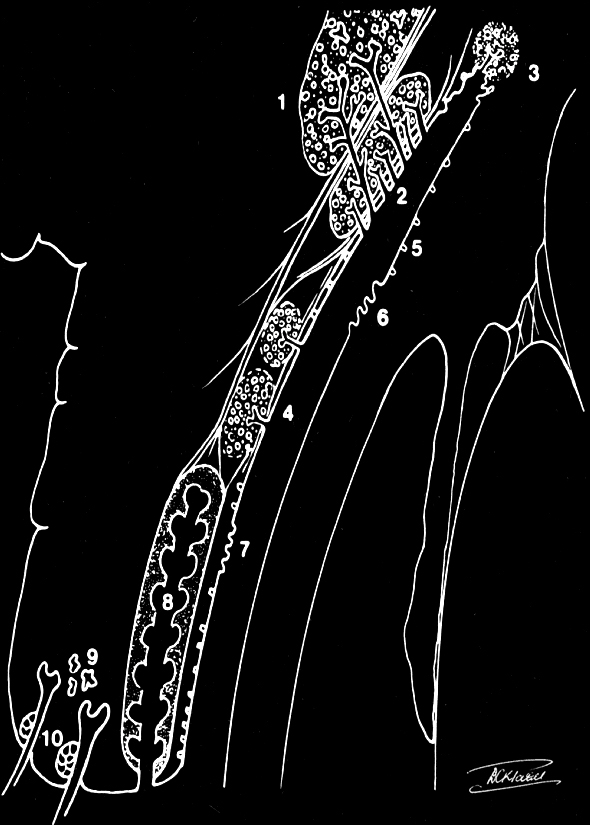

Probing of the Canaliculi

This test is done to determine the patency of the canaliculi and detect any scars, constrictions, or foreign bodies in the canaliculus.

With the application of topical anesthesia, an 00 Bowman probe is lubricated with ointment and passed gently through the punctum and down the canaliculus with lateral traction on the eyelid. The point of obstruction can be measured. A soft stop in the canaliculus indicates a canalicular obstruction or scar. If the inner canthus moves when one hits a stop, it indicates that the obstruction is at the common canaliculus. A hard stop against the bone behind the lacrimal sac indicates that the probe has passed through the canaliculus and into the lacrimal sac. We probe with the Bowman probe, which is softer and more rounded than the cannula. No force should be applied when performing this test. Ascertaining the level of obstruction is essential as it will determine the type of surgery that has to be undertaken. Both the upper and lower canaliculi should be irrigated and probed to obtain a complete assessment of the proximal drainage system. The nasolacrimal duct used to be probed in the clinic in the past, but that is no longer performed.[7] Also, probing of the nasolacrimal duct in adults is not useful as the obstruction in the nasolacrimal duct is caused by firm fibrosis and is not amenable to dilatation. In congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction, the obstruction is usually at the inferior nasolacrimal duct and is membranous, thereby responding to therapeutic probing.

Nasal Endoscopy

Nasal examination, at the very least with a light pipe, is essential as nasal tumors, foreign bodies, and scarring can be detected. Many units now have endoscopy available in the clinic to examine the nasal cavity, the turbinates, the nasal septum, and the lacrimal sac fossa.

Dacryocystography (DCG)

DCG is used to determine the anatomical patency of the nasolacrimal system but is used less often now. Contrast DCG, followed by computerized digital subtraction imaging, is sometimes performed, especially if a lacrimal sac tumor is suspected. DCG gives excellent structural detail but has the risk of punctal or canalicular trauma when inserting cannulas, and there is radiation exposure. It is a non-physiological test done for the assessment of structural integrity alone.

Dacryoscintigraphy (DSG)

Dacryoscintigraphy uses radionucleotide drops (10 micrograms of TC-99) in the inferior fornix and tear flow with a scintigram gives physiological information of tear flow. The test involves imaging the lacrimal system sequentially to capture the physiological flow of the tracers through the lacrimal system. This is mostly used in research studies.

Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

These are useful following trauma in congenital craniofacial diseases and when looking for neoplasia. Bony abnormalities are better delineated with CT, which also allows the determination of the level of the cribriform plate. CT and MRI are both used to assess nasal and sinus disease.[8]

Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Dacryocystography (MRDCG)

This allows structural assessment as well as the functional assessment of tear flow. Recent modifications allow dynamic contrast flow, but a false positive is found in up to 30% of cases.[9]

Assessment of the Pediatric Patient with Epiphora

Epiphora is a common problem in children. In a large epidemiological study, MacEwen et al. found the prevalence of epiphora to be 20 percent in the first year of life in British infants. Interestingly, 95% of these children presented with symptoms by the age of one month.[1]

Examination of the face for clefting syndromes, other syndromes (Treacher Collins, Down syndrome, Tessier clefts #3 or #4), and local periorbital deformities (colobomas), nasal deformities, and facial asymmetry is performed.

Very young children may need to have an examination under anesthesia. Examination of the puncta, the upper and lower eyelids (looking for trichiasis, distichiasis, epiblepharon, frank entropion, retraction, lagophthalmos, canthal dystopia), and the medial canthal region (looking for a mucocele, lacrimal fistula) may be carried out in the clinic. However, in the very young, an examination under anesthesia is often needed to carry out a detailed examination.

Pressure over the lacrimal sac may reveal a mucocele. The flow of mucoid material from the puncta will confirm the presence of a nasolacrimal duct obstruction. This is often called the "regurgitation test" and may be used in adults and children.

The puncta are assessed for the presence of normal puncta, accessory puncta, patency, and position. Some children may have a simple membrane over the punctum, while others may have maldevelopment of the whole punctum, in which case, the punctum, and the papilla will be maldeveloped. There may be no lid margin indication of an underlying punctum in true agenesis of the canaliculus and punctum.

Schirmer's secretory tests: Shirmer I test (without topical anesthetic) to measure the reflex tear production may be performed but is only really possible in older children.

Irrigation of the lacrimal system: in young children, this is best performed while examining under anesthesia. When accessory puncta are present, or there is a fistula, irrigation through all the openings is performed to try to determine the exact anatomy of the abnormal excretory lacrimal system. In such patients, dacryocystography is useful.

Jones I and Jones II excretory tests are rarely useful in the pediatric age group. Some surgeons apply a drop of fluorescein into the inferior conjunctival recess and examine the nose using an otoscope with a cobalt blue filter after five minutes: the aim is to look for the flow of fluorescein under the inferior meatus. As it is important to keep the child upright and blinking normally, this test has variable reliability and is now rarely performed.

Nasal examination, looking for abnormalities of the turbinates and any nasal masses, is usually carried out under anesthesia.

The cornea is examined for any surface disease (herpetic disease, foreign bodies), and intraocular pressure measured as congenital glaucoma may present with epiphora. The anterior chamber is examined for evidence of iritis, which can also present with a photophobic, red, teary eye.

If there is swelling of the lacrimal sac at birth, it may be caused by a dacryocystocele (also called an amniotocele) or a dacryocystitis. The differential diagnosis includes encephalocele (the swelling will be more in the midline), hemangioma, orbital cellulitis, and solid tumors such as rhabdomyosarcoma, which are rarer in newborns. CT and/or MRI imaging may be necessary to determine the diagnosis. If a diagnosis of dacryocystocele is reached, simple massage over the swelling with topical antibiotic drops suffices. We institute massage over both lacrimal sacs three to four times a day with the thumb and index finger on either side of the nasal bridge, which reduces the risk of trauma to the eye. Probing is only necessary if this conservative treatment fails.

Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction may present in 3 to 6% of newborns, and in 20%, it occurs bilaterally. Most children will present not only with tearing but also a mucoid discharge from one or both eyes. Gentle massage is instituted, and probing is only attempted once the child is 12 months or more as most of these obstructions (90%) will resolve by then.[10] Furthermore, anesthesia is safer in children after the age of 12 months. The only exception will be if an acute dacryocystitis does not settle with conservative treatment.

Clinical Significance

A methodical approach to the assessment of a patient will epiphora will allow a diagnosis to be made and treatment planned.

Application of the Schirmer's Test in Patients Undergoing Upper or Lower Blepharoplasty

For patients who are undergoing upper or lower blepharoplasty, it is important to ensure that symptoms and signs that may indicate current or postoperative dryness of the eyes should be assessed carefully. These include:

- History of prior eyelid surgery

- History of prior corneal laser surgery

- History of dry eyes

- Symptoms of scratchiness or grittiness

- Scleral show

- Slow blink (Parkinson disease, myasthenia gravis)

- Lagophthalmos

- Negative malar vector

- Lower eyelid laxity

- Lower eyelid snapback test

The value of routine preoperative Schirmer's tests in patients undergoing blepharoplasty has been debated. McKinney reported that abnormal tear film breakup time and Schirmer's test were not good predictors of postoperative dry eyes after blepharoplasty. However, if a patient presents with symptoms and signs which indicate current or future dryness, Schirmer's test can be useful. A reading below 5 mm should suggest that the patient be investigated and treated by an ophthalmologist. There is decreased tear production with increasing age, and pathology studies have shown progressive acinar atrophy and fibrosis of the lacrimal glands with increasing age.[11][12] Furthermore, Sjögren syndrome, which presents with lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands, including the lacrimal glands, has a strong female propensity, is more prevalent in White race women, and presents in the 4th and 5th decade of life: these are the very patients who seek cosmetic and functional blepharoplasty. The incidence of Sjögren syndrome has been found to be 3.9 to 5.3 per 100,000, with women affected 10 to 20 times more than men.[13]