Introduction

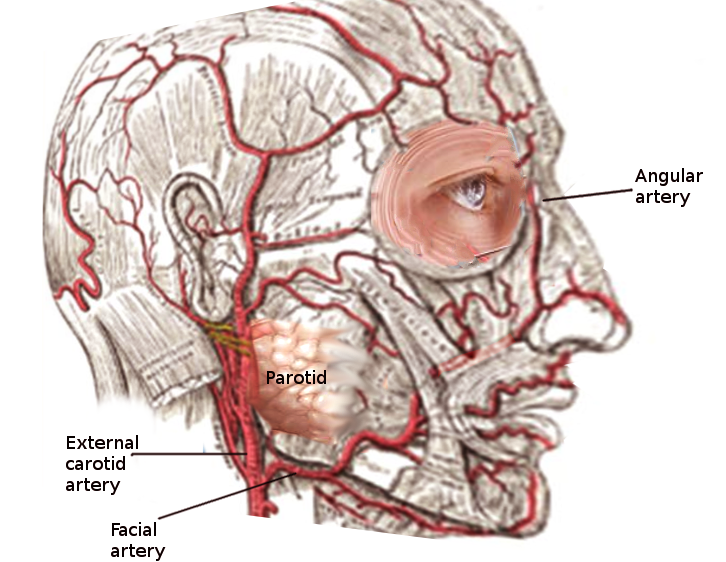

The facial artery is a branch of the external carotid artery that supplies the anatomic structures of the superficial face. The facial artery arises from the carotid triangle which is formed by the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle, the sternocleidomastoid, and the posterior belly of the digastric. The facial artery originates deep to the platysma and quickly becomes superficial. The tortuous course of this artery allows for more stretch during facial actions such as mastication. As it courses on the face, the vessel travels deep to the posterior belly of the digastric and stylohyoid muscles. It then continues along the posterior surface of the submandibular gland.[1] The artery curves upward over the body of the mandible and courses along the anteroinferior border of the masseter. The pulse of the facial artery is palpable as it crosses the mandible. The artery continues superiorly at an oblique angle across the cheek towards the oral commissure then ascends along the side of the nose terminating at the medial canthus of the eye as the angular artery.[2]

Structure and Function

The facial artery has multiple branches that supply many structures. Supplied by the facial artery, the buccinator and levator anguli oris are two muscles that lie deep to this vasculature. The artery may pass through, or over (normal variant), the levator labii superioris.[3] Other musculature supplied by the facial artery include the levator veli palatini, masseter, mentalis, mylohyoid, nasalis, palatoglossus, palatopharyngeus, platysma, procerus, risorius, styloglossus, and the transverse portion of the nasalis. It also supplies the palatine tonsils, soft palate, pterygoid muscles, digastric muscles, and the submandibular gland.

The facial artery has a cervical branch that gives rise to four other vessels before continuing its course into the face. The vessels of the cervical branches are the ascending palatine artery, tonsillar branch, submental artery, and glandular branches. On the face, four main vessels arise from the trunk of the facial artery: the inferior labial artery, superior labial artery, lateral nasal branch (to the nasalis), and the angular artery.[4] The angular artery is the terminal segment of the facial artery.

Embryology

During the 4th and 5th weeks of embryological development, the aortic sac gives rise to the aortic arches. The external carotid artery develops from the 3rd aortic arch and gives rise to the facial artery.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The origin of the facial artery is near the deep superior cervical lymph nodes. The submandibular lymph nodes lie adjacent to the facial artery as it courses toward the face superficially. As the artery crests over the body of the mandible, the submandibular and facial lymph nodes remain deep to this vessel.

Nerves

The hypoglossal nerve travels deep to the proximal facial artery. It is also not uncommon to see the facial artery traverse deep to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve.[6]

Muscles

In the neck, the facial artery starts deep to the platysma and quickly becomes superficial. The facial artery traverses superior to the stylopharyngeus, styloglossus, and hyoglossus muscles. It travels along the inferior surface of the posterior belly of the digastric and stylohyoid muscles. The artery then enters a groove on the posterior surface of the submandibular gland and follows an upward trajectory over the body of the mandible as it courses along the anteroinferior border of the masseter. On the face, the facial artery remains superficial to the buccinator and levator anguli oris muscles.[1]

Physiologic Variants

Similar to other vasculature in the body, the facial artery can have many anatomical variations. It may arise as a single vessel from the linguofacial trunk or a thyrolinguofacial trunk.[7] In the absence of an external carotid artery, the facial artery may arise from either the internal carotid artery or common carotid artery.[7] Some clinically significant variations include an enlarged facial artery, a hypoplastic facial artery, and agenesis of the facial artery.

Surgical Considerations

Procedures involving the Facial Artery

The facial artery has a role in the reconstructive procedures of the face. It can act as the vascular supply for various flaps including local flaps, regional flaps, or free flaps.[8] Common flaps that use the facial artery include submental, platysma muscle, nasolabial, buccinator myomucosal, and facial artery musculomucosal flaps.[8] These types of reconstructive procedures can be performed following resection of tumors in the head and neck. Due to its robust nature, the facial artery can adequately supply grafted tissue.

Complications associated with the Facial Artery

The facial artery can have implications in complications associated with various surgical procedures. Prevention of trauma to the facial artery is paramount. Thus, excessive retraction in this area should be avoided. Hemorrhage from the facial artery can occur during submandibular gland excision as well.[9] External approaches to mandible fracture repair can require ligation of the facial artery. If this is needed, careful documentation should be made in the operative note for use as a reference by potential future surgeons. If bleeding from the facial artery occurs, direct pressure should be applied to the angle of the mandible over the vessel until the vessel is identified and bleeding controlled.

It is also important to recognize the proximity of various nerves, including the hypoglossal nerve, to the facial artery during surgical procedures. These structures need to be identified early and preserved to minimize post-operative complications.

Clinical Significance

Due to its superficial course, the pulse of the facial artery is palpable at the anteroinferior angle of the masseter muscle against the bony surface of the mandible.

Documentation exists that pulsation of the angular artery (terminal branch of the facial artery) is present and strong in about 70% of internal carotid artery occlusion cases.[[10] There are anastomotic channels between the angular branch of the facial artery and the medial branches of the infraorbital artery on the external carotid side and the dorsal nasal and supratrochlear branches of the ophthalmic artery on the internal carotid side.[10] However, the diagnostic utility of this finding is limited as it is a normal finding in 1 of 10 adults over the age of 55 with long-standing hypertension.[10]

Atherosclerosis of the common carotid artery is a risk factor for embolic events leading to ischemic injury. If there is a weakness in the superficial facial musculature, it is possible for there to be a vascular compromise of the facial artery. An embolus from the common carotid may travel and cause ischemic injury to a distal branch of the facial artery. However, this is a rare sequela of carotid artery atherosclerosis.