Introduction

The human brain is made up of approximately 86 billion neurons that “talk” to each other using a combination of electrical and chemical (electrochemical) signals.

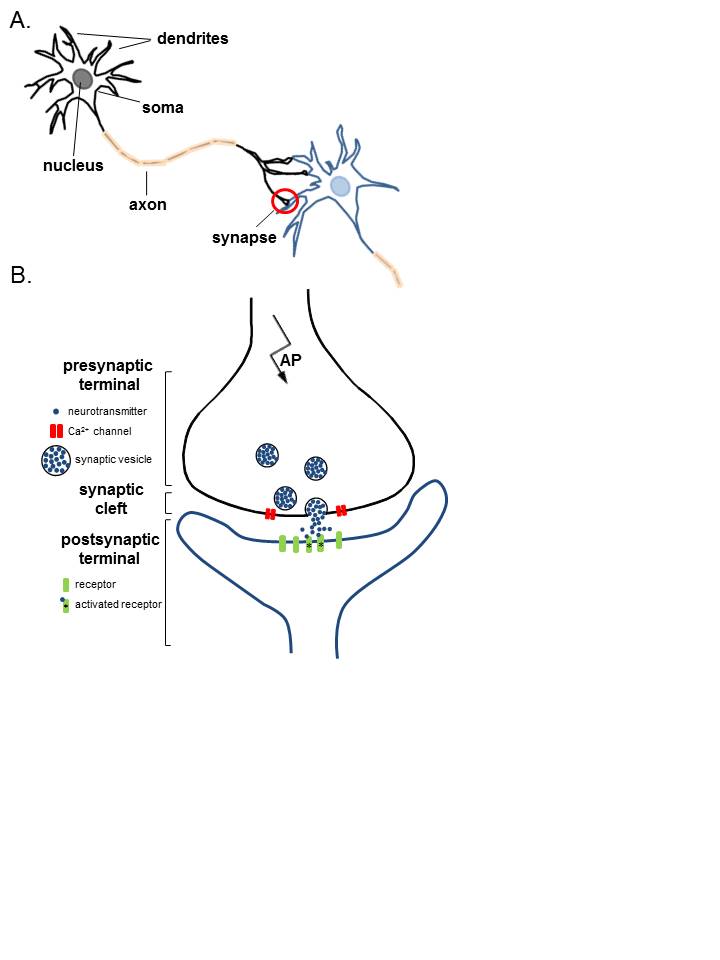

The places where neurons connect and communicate with each other are called synapses. Each neuron has anywhere between a few to hundreds of thousands of synaptic connections, and these connections can be with itself, neighboring neurons, or neurons in other regions of the brain. A synapse is made up of a presynaptic and postsynaptic terminal.

The presynaptic terminal is at the end of an axon and is the place where the electrical signal (the action potential) is converted into a chemical signal (neurotransmitter release). The postsynaptic terminal membrane is less than 50 nanometers away and contains specialized receptors. The neurotransmitter rapidly (in microseconds) diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to specific receptors.

The type of neurotransmitter released from the presynaptic terminal and the specific receptors present on the corresponding postsynaptic terminal is critical in determining the quality and intensity of information transmitted by neurons. The postsynaptic neuron integrates all the signals it receives to determine what it does next, for example, to fire an action potential of its own or not. [1][2]

Cellular Level

Neurons

In the simplest sense, the neuron consists of a cell body, axons, and dendrites.

Cell Body

The cell body contains the nucleus and is the site of metabolic activity. Most of the neurotransmitters that will eventually be released at the synapse are synthesized here.

Dendrites

These are small projections from the cell body that serves a receptive role in the physiology of the neuron. They receive incoming signals from other neurons and relay them to the cell body, where the signals are integrated, and a response will be initiated.

Axons

Generally, the outflow tract of the neuron. It is a cylindrical tube that is covered by the axolemma and is supported by neurofilaments and microtubules. The microtubules will help to transport the neurotransmitters from the cell body down to the pre-synaptic terminal, where they will be released.

Synapses

The synapse itself is the site of transmission from the pre-synaptic neuron to the post-synaptic neuron. The structures found on either side of the synapse vary depending on the type of synapse:

Axodendritic

A connection formed between the axon of one neuron and the dendrite of another. These tend to be excitatory synapses.

Axosomatic

A direct connection between the axon of one neuron to the cell body of another neuron. These tend to be inhibitory synapses.

Axoaxonic

A connection between the terminal of one axon and another axon. These synapses generate serve a regulatory role; the afferent axon will modulate the release of neurotransmitters from the efferent axon.

The above discussion focuses on chemical synapses, which involve the release of a chemical neurotransmitter between the 2 neurons. This is the most common type of synapse in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS). However, it is important to note that there are electrical synapses, where electrical current (or signals) will pass directly from one neuron to another through gap junctions. The differences between the two will be expanded on in the mechanism section. [3][4]

Development

Two neurons form the neurological synapse, or in some instances, a neuron and an anatomical structure. This review will focus on 2 neurons composing the synapse. Neurons initially develop from the embryonic neural tube, which has 3 layers:

- The ventricular zone, which surrounds the central canal of the tube. This tube will eventually become the ependyma.

- The intermediate zone, which is formed by dividing cells of the ventricular zone. This zone stretches from the outermost portion of the ventricular zone to the outermost layer of the neural tube, known as the pial layer.

- The marginal zone, which is formed by extensions of the nerve cells of the intermediate zone.

The intermediate zone will go on to form the gray matter, while the nerve processes that make up the marginal zone will become white matter once myelinated.

The neurons must then differentiate from their precursors. The order in which they do this is based upon their size, with the largest neurons (motor neurons) differentiating first. Around the time of birth, the smaller neurons (sensory neurons) will develop, along with glial cells. Glial cells are cells that will aid in the differentiation of the neurons and will facilitate their growth in the direction of their target locations. Later, glial cells will participate in the reuptake of excess neurotransmitters in the synaptic cleft.

Mechanism

Synapses

As previously mentioned, there are 2 major types of synapses: electrical and chemical.

In mammals, the majority of synapses are chemical. Chemical synapses can be differentiated from electrical synapses by a few distinguishing criteria: they use neurotransmitters to relay the signal and vesicles are used to store and transport the neurotransmitter from the cell body to the terminal; furthermore, the pre-synaptic terminal will have a very active membrane and the post-synaptic membrane consists of a thick cell membrane made up of many receptors. In between these 2 membranes is a very distinct cleft (easily visualized with electron microscopy) and the chemical neurotransmitter released must diffuse across this cleft to elicit a response in the receptive neuron. Because of this, the synaptic delay, defined as the time it takes for current in the pre-synaptic neuron to be transmitted to the post-synaptic neuron, is approximately 0.5 to 1.0 ms.

This is different from the electrical synapse, which will typically consist of 2 membranes located much closer to each other than in a chemical synapse. These membranes possess channels formed by proteins known as connexins, which allow the direct passage of current from one neuron to the next and do not rely on neurotransmitters. The synaptic delay is significantly shorter in electrical synapses versus chemical synapses.

The rest of the discussion will focus on chemical synapses, which have a lot of variation and diversity of their own. They vary not only between shape and structure, but also the chemical that is transmitted. Synapses can be excitatory or inhibitory, and use a variety of chemical molecules and proteins that will be discussed shortly.

Multiple types of neurotransmitters used in synaptic communication including, but not limited to:

- Acetylcholine (ACh): One of the most important neurotransmitters found in multiple synapses in the body, including, but not limited to, the neuromuscular junction, autonomic ganglia, caudate nucleus, and the limbic system. Generally, ACh is an excitatory neurotransmitter at the neuromuscular junction and in the autonomic ganglia. In the brain, Ach is synthesized in the basal nucleus of Meynert.

- Norepinephrine (NE): The most important molecule in sympathetic nervous system signaling, except for the sweat glands. In the brain, NE is mainly found in the locus coeruleus and lateral tegmental nuclei.

- Dopamine (DA): Dopamine signaling is generally inhibitory. There are three major dopaminergic pathways in the brain, the nigrostriatal, mesolimbic, and mesocortical; each of which serve different roles. One of the most well-known disease states involving dopamine is Parkinson's disease, where there is degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra.

- Serotonin (5-HT): Produced from tryptophan using tryptophan hydroxylase, which is mostly found in the brain (raphe nucleus) and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Serotonin is mostly known for its role as a regulatory neurotransmitter and is therefore implicated in various mood states and diseases.

- Other common neurotransmitters include other catecholamines, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glycine, and glutamic acid.

The easiest approach to understanding synaptic transmission is to think of it as a stepwise process beginning with the synthesis of the neurotransmitter and ending with its release.

- Synthesis: The neurotransmitter is synthesized in the cell body, where it will then be transmitted down the microtubules of the axon to the pre-synaptic terminal, or it is synthesized directly in the pre-synaptic terminal from recycled neurotransmitters. The neurotransmitter is then stored in presynaptic vesicles until its release.

- Release: The neurotransmitter is released in a regulated fashion from the pre-synaptic neuron into the synaptic cleft.

- Receptor activation: The neurotransmitter binds to post-synaptic receptors and produces a response in the post-synaptic neuron.

- Signal termination: The signal must be terminated by some mechanism, normally by the elimination of excess neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft.

Synthesis

Neurotransmitters are synthesized differently depending on which type they are. They can be a small molecule chemical, such as dopamine and serotonin, or they can be small neuropeptides, such as enkephalin.

- Neuropeptides are synthesized in the cell body using the typical protein synthesis and translation pathways (rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus), then will be packaged into large, dense-core vesicles along with a protease. These vesicles are rapidly transported down the axon using microtubular proteins such as kinesin. When they arrive at the pre-synaptic terminal, they are ready to be released.

- Small molecule neurotransmitters are synthesized in the cell body, where they are then transported down the axon in small, clear core vesicles. Upon arriving at the pre-synaptic terminal, enzymes will modify the small molecule neurotransmitter, and they can then be released from the vesicles into the cleft.

Release

Now that the neurotransmitters are stored in the vesicles in the pre-synaptic terminal, they must be released into the cleft. Along the membrane of the vesicle and the presynaptic membrane are proteins known as SNARE proteins; these proteins are essential in the binding of the vesicles to the membrane and the release of their contents. As the action potential propagates down the pre-synaptic neuron, the membrane will depolarize. Once the action potential arrives at the pre-synaptic terminal, the depolarization of the membrane will allow the voltage-dependent calcium channels to open, allowing the rapid influx of calcium into the pre-synaptic terminal. The influx of calcium causes the SNARE proteins to activate and change conformation, allowing the fusion of vesicles to the membrane and the release of their contents. The neurotransmitter will spill into the synaptic cleft, and the vesicle membrane is recovered via endocytosis.

Receptor Activation

Once the neurotransmitter binds to the post-synaptic neuron, it can generally cause one of 2 types of receptors to be activated. It will either activate a ligand-gated ion channel or a G-protein receptor.

- Ligand-Gated Ion Channel: When the neurotransmitter binds to this receptor, there is a direct opening or closing of the attached ion channel. In other words, the neurotransmitter acts directly on the target ion channel. This type of receptor is described as “fast” because it generally only takes a few milliseconds to produce a response and is terminated very quickly. Depending on which neurotransmitter is binding to the receptor, these types of receptors can be excitatory or inhibitory.

- G-Protein Coupled Receptors: These types of receptors are will produce a response (open or close an ion channel) by activating a signaling cascade involving secondary messengers. The most common secondary messengers are cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), inositol triphosphate (IP3), and diacylglycerol (DAG). When the neurotransmitter binds to the receptor, it activates the G-protein, which binds to guanosine triphosphate (GTP), and is activated. This will activate the secondary messenger cascade, which will eventually lead to the phosphorylation of ion channels. Due to multiple steps having to take place to generate the final response, this pathway is generally described as “slow,” and generally, the effects last longer (seconds to minutes).

Signal Termination

Inactivation of the signal must involve clearing the neurotransmitter from the synapse in at least 1 of 3 ways:

- Re-uptake: Re-uptake can either be pre-synaptic or by glial cells. One important point to remember involving reuptake is that only small molecule chemical neurotransmitters can be taken back up, neuropeptides cannot participate in re-uptake; they must be eliminated by other means, such as degradation.

- In pre-synaptic reuptake, the pre-synaptic neuron will use either endocytosis or specific transporters to remove the neurotransmitter from the synapse. The advantage of this mechanism is that the neurotransmitter can be recycled, which will prevent the neuron from having to re-synthesize the neurotransmitter every cycle of release.

- In some cases, such as with glutamate, a glial cell will be involved in the re-uptake. Glutamate is toxic to the cell, so it is stored inside the neuron as glutamine. When glutamate is released into the synapse, it will be taken up by the glial cell using a specific transporter, converted into glutamine via glutaminase, then returned to the neuron to be recycled.

- Enzymatic Destruction: The neurotransmitter can be destroyed directly either in the cleft or in the pre-synaptic terminal using certain enzymes. Two major enzymes are involved in the destruction of the neurotransmitter:

- Monoamine Oxidases (MAO): These enzymes are responsible for oxidizing, and therefore inactivating, the monoamines. They do this by using oxygen to remove the amine group. These are split into MAO-A and MAO-B based on substrates. MAO-A is mostly responsible for breaking down serotonin, melatonin, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Both forms break down dopamine, tyramine, and tryptamine equally. MAO-B also breaks down phenethylamine and benzylamine.

- Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT): Generally, COMT is responsible for degrading catecholamines, including dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, as well as most substances with a catechol structure.

It is important to note that both of the above enzymes are very frequent targets of therapeutic medications. By eliminating these enzymes, the neurotransmitter will remain in the synapse for longer, which can be beneficial in eliminating the symptoms of many disease processes.

- Diffusion: In the simplest form of termination, the neurotransmitter can simply diffuse out of the synaptic cleft and away from the receptors and into nearby blood vessels. This will decrease the concentration of the neurotransmitter in the synapse, gradually reducing the effect the neurotransmitter has on the post-synaptic neuron. [5][6]

Clinical Significance

The synapse is the fundamental functional unit of neuronal communication. Because of this, diseases that target the synapse can present with severe clinical consequences. A few examples are listed below:

Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia gravis is an auto-immune disease process that causes muscle weakness that usually presents in a descending fashion. It can cause ptosis, diminished facial expression, respiratory depression, and other signs/symptoms of weakness. In general, it is worse after activity and better with rest. The pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis involves diminished communication between the neuron and the muscle at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The reason for this is that antibodies will either block or destroy the acetylcholine receptors at the NMJ, preventing the ACh from binding and depolarizing the muscle, therefore, inhibiting contraction. These antibodies block step three (receptor activation) of the synaptic communication pathway.

Lambert-Eaton Syndrome

Lambert-Eaton syndrome is also an auto-immune condition producing dysfunction at the neuromuscular junction; however, it involves the pre-synaptic neuron. Instead of antibodies directed against the ACh receptors as in myasthenia gravis, the antibodies here are directed against the calcium channels on the pre-synaptic neuron. This prevents calcium influx from occurring, which prevents the fusion of vesicles with the pre-synaptic membrane and the release of the neurotransmitters into the synapse. These antibodies prevent step two (neurotransmitter release) of the synaptic communication pathway.

Botulism/Tetanus

In both of these disease processes, the causative agent is a toxin produced by a bacteria that acts as a protease that cleaves the SNARE proteins. This prevents the release of neurotransmitters at the junction by inhibiting vesicular fusion.

- Botulism: The botulinum toxin, produced by Clostridium botulinum, prevents the release of acetylcholine, which is a stimulatory neurotransmitter. This inhibits stimulatory effects, which prevents muscle contraction and causes flaccid paralysis.

- Tetanus: The tetanus toxin, produced by Clostridium tetani, prevents the release of GABA and glycine, both of which are inhibitory neurotransmitters. Specifically, their release is inhibited in the Renshaw cells in the spinal cord. This produces symptoms resembling an upper motor neuron lesion: spastic paralysis, lockjaw, and opisthotonus.