Continuing Education Activity

The inferior gluteal nerve supplies the gluteus maximus muscle. The inferior gluteal nerve provides motor function to gluteus maximus, a major muscle involved in hip extension, as well as external rotation of the hip joint. The nerve does not confer any sensation. Injury to this nerve is most commonly iatrogenic in origin and is the most at risk nerve during total hip arthroplasty via a posterior approach. This activity reviews the anatomy and function of the nerve, and the sequelae observed when the nerve is injured, and how nerve injuries are managed by an interprofessional team.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of inferior gluteal nerve injuries.

- Review the appropriate evaluation of inferior gluteal nerve injuries.

- Outline the management options available for inferior gluteal nerve injuries.

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the care of inferior gluteal nerve injuries and improve outcomes.

Introduction

The inferior gluteal nerve orientates from the sacral plexus, carrying fibers from the dorsal branches of the ventral rami of L5, S1, and S2 nerve roots.[1] The inferior gluteal nerve provides motor function to the gluteus maximus, a major muscle involved in hip extension, as well as external rotation of the hip joint. The nerve does not confer any sensation.

Course

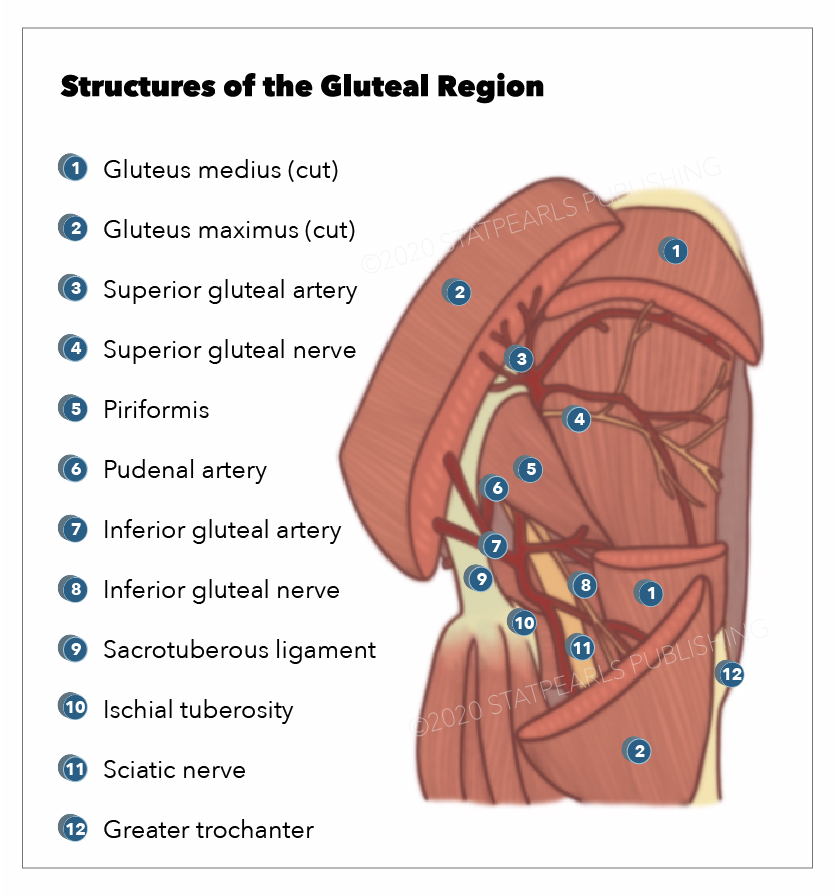

The inferior gluteal nerve is a branch of the sciatic plexus. It initially lies anterior to the piriformis muscle in the pelvis. The inferior gluteal nerve typically exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen, coursing underneath the piriformis muscle before dividing into several branches. These branches continue posteriorly and enter the gluteus maximus muscle on its deep surface. The inferior gluteal nerve courses the deep surface of the gluteus maximus 5 to 6 cm from the tip of the greater trochanter and the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and entering into the inferior third of the muscle belly. The inferior gluteal nerve is always seen in close relation to the inferior gluteal artery.[2]

Function

The inferior gluteal nerve is a motor nerve to the gluteus maximus. It is therefore responsible for extending the trunk from a forward bending position and extending the hip from sitting-to-standing activity or during stair-climbing or rising from a squatted position.[3]

Etiology

Injury to the inferior gluteal nerve is most commonly iatrogenic in origin. Total hip arthroplasty is the most common surgical procedure in which the inferior gluteal nerve can be injured.[1] Other causes may include trauma, entrapment, and compression, or ischemia to the nerve.[4] All forms of injury typically often lead to an altered gait pattern known as gluteus maximus ‘lurch.’ This is further explained in ‘sequelae.’

Total hip arthroplasty is commonly performed via the posterior approach to the hip. This approach to the hip carries the highest risk of injury to the inferior gluteal nerve. It is the preferred approach to the hip for both primary and revision arthroplasty due to its visualization of the femoral shaft. In this approach, there is no exact inter-nervous plane, and the inferior gluteal nerve is often not visualized. The likelihood of inferior gluteal nerve injury is highest when a muscle-splitting incision across the gluteus maximus. This can damage the inferior gluteal nerve through numerous means: direct trauma to the nerve from sharp dissection, devascularisation of the nerve, or stretching/crushing the nerve from instrumentation. The inferior gluteal nerve injury may be partial or complete, dependent upon whether branches of the nerve have been injured or the nerve proper.[5][6][7][8][9]

Two other often cited causes for the inferior gluteal nerve are entrapment (piriformis syndrome) and peri-sacral surgery. The infra-piriformis foramen can compromise any nerve (or vessel) passing through it, leading to symptoms of inferior gluteal nerve entrapment. If this persists, ipsilateral atrophy of the gluteus medius muscle will follow.[9] Peri-sacral surgery, particularly in the circumstances of tumor surgery, can present several challenges. The surgeons must have clearly defined landmarks to preserve superior and inferior gluteal nerves and arteries. The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments can act as reference landmarks to assist the identification of the superior and inferior gluteal arteries, which run over these ligaments. Preserving as much musculature as is safe to do so will also aid the preservation of function.[10]

Even though the inferior gluteal nerve is usually defined in the literature as a single nerve with only motor innervation, but in a recent study, it has been found that it often gives 1 to 2 cutaneous branches (75%). These cutaneous nerves carry sensations from the skin over the greater trochanter. This knowledge is quite crucial for orthopedic surgeons during hip surgery and pain specialists during the management of gluteal pain syndrome.[11]

Epidemiology

No statistics are available in the literature about the frequency of inferior gluteal nerve injuries at present.

History and Physical

The sequelae of an inferior gluteal nerve injury are denervation of the ipsilateral gluteus maximus muscle, commonly known as gluteus maximus ‘lurch.’ This results from the weakening or absence of an ipsilateral hip extension. Clinically, patients may also report wasting of the ipsilateral gluteus maximus muscle and loss of the defined shape to the affected buttock.

In a normal gait cycle, the gluteus maximus will begin to contract at the moment of the ipsilateral heel-strike to initiate ipsilateral hip extension. Consequently, the gait is affected in patients with inferior gluteal nerve injury: the trunk will extend (lean back) when the heel strikes on the ground on the affected side to compensate for weak/absent hip extension. The characteristic backward trunk lurch is present in the whole stance phase of the gait cycle and also maintaining the middle of mass posterior to the hip joint and therefore locking the hip in extension. In some cases, the hamstrings muscle compensate to an extent.

The Gluteus maximus does not play an essential role in posture: it remains relaxed in the standing position and has a minor role in walking. It mostly comes into action during running, climbing, standing from a sitting position, and rising from a squatted position. It also contributes to the control of hip flexion when entering a seated position.

Evaluation

Diagnosis is typically reached clinically through a combination of taking a relevant history and physical examination. Some imaging modalities (radiography, CT, US, MRI) may play a role in excluding other differential diagnoses. Neuroconductive studies may be used to supplement the clinical findings to aid the diagnosis of an inferior gluteal nerve injury.

Treatment / Management

Peripheral Nerve Injury

Peripheral nerve injuries (PNIs) can vary in type and severity. Stretching, transection (or laceration), and compression are the most common types of PNI. Seddon classified the severity of PNI in terms of the three degrees of injury. These are neuropraxia (local myelin damage secondary to compression), axonotmesis (axon discontinuity but epineurium intact), and neurotmesis (complete disruption to the entire nerve trunk).

Sunderland further developed the classification by suggesting three grades of axonotmesis. In grade I axonotmesis, the axon has been severed, but the endoneurium remains intact (this is considered to be the optimal circumstance for regeneration). In grade II axonotmesis, there is a discontinuity of the axon and endoneurial tube, but the perineurium and fascicular arrangements are intact. In grade III axonotmesis, there is a discontinuity of the axon, endoneurial tube, perineurium, and fasciculi, but the epineurium is intact.[12]

Management

The management of inferior gluteal nerve injuries will be dictated by the type and severity of the nerve injury.[13] Open wounds can be surgically explored to assess the continuity of the nerve and the extent of the damage. Nerves that have undergone sharp transection (e.g., during total hip arthroplasty) should ideally undergo end-to-end repair with 72 hours to avoid retraction of the proximal and distal stumps, and early repair is associated with better outcomes. Conversely, blunt transection injuries usually undergo a delayed surgical repair within 2-3 weeks for the damaged nerve ends to scar. These scarred nerve ends can then be resected to healthy margins, and the ends can be repaired with or without a nerve graft. Open injuries without nerve transection can be managed conservatively. In the first instance, with serial evaluations utilizing clinical examination, neurophysiology diagnostics, and radiological investigations.[14]

Closed nerve injuries are managed conservatively in the first instance as the nerves often remain in continuity. Suspected neuropraxia and axonotmesis injury are monitored with serial evaluations utilizing clinical examination, neurophysiology diagnostics, and radiological investigations. At 3 to 4 months post-injury, an absence of signs of re-innervation is suggestive of neurotmesis. Such conditions necessitate surgical exploration and the use of intra-operative neurophysiology diagnostics.

Physiotherapy and rehabilitation also have a role in the patients' recovery.

Differential Diagnosis

The majority of cases will result from iatrogenic trauma during total hip arthroplasty (THA). It is essential to consider other principal differential diagnoses, which include: vascular pathology, tumors, nerve entrapment, and infections. A thorough history and physical examination will likely lead to the true differential.

The presence of hypesthesia over the area of the inferior lateral buttock and an inferior gluteal nerve neuropathy can be early indicators of recurrent colorectal malignancy.[15]

As the inferior gluteal nerve passed deep to the gluteus maximus muscle, the intramuscular augmentation gluteoplasty can be conducted superficially, efficiently, and safely without injury to the nerve.[16]

Now it is known that during sacrospinous ligament fixation, damage to the inferior gluteal nerve doesn't seem to cause postoperative gluteal pain. This pain may be instead because of the branches coming from S3/S4 nerves.[17]

Prognosis

Similar to the epidemiology, no statistics are available in the literature about the prognosis of inferior gluteal nerve injuries at present.

Complications

The key complications in inferior gluteal nerve injuries are alteration of the gait cycle (gluteus maximus 'lurch') and wasting of the ipsilateral gluteus maximus muscle leading to loss of the defined shape to the affected buttock, as described earlier. Changes in gait patterns can have both short-term and long-term implications on a patient's physical and mental wellbeing.

Deterrence and Patient Education

All patients undergoing surgical procedures where this nerve is at risk should be appropriately counseled regarding this prior to consenting to surgery.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach should be taken to managing patients affected by inferior gluteal nerve injuries. As the cause, if often iatrogenic in origin, key members of the team would include the operating surgeon (and their team), physiotherapists, and occupational therapists. However, nurses and other allied health professionals may also be required. Prior to any surgical intervention, the patient must appropriately consent to the potential risks and complications.