Introduction

The major and minor psoas muscles and the iliacus muscle make up the iliopsoas musculotendinous unit (IPMU). Commonly called iliopsoas muscle. This complex muscle system can function as a unit or intervene as separate muscles. It is essential for correct standing or sitting lumbar posture, stabilizing the coxofemoral joint, and is crucial during walking and running. The fascia covering the iliopsoas muscle creates multiple fascial connections, relating the muscle to different viscera and muscle areas. Several disorders can affect IPMU at the level of its insertion (tendon) or involving the fleshy part. To solve these dysfunctions, the doctor will indicate which therapy will be most useful, conservative or surgical, as well as physiotherapy or an osteopathic approach. There are multiple anatomical variations of IPMU, and in case of pain and disturbances, it is important to perform instrumental examinations before making a precise diagnosis. With the current scientific knowledge, one can not imagine anatomy as segments but rather as a functional continuum.

Structure and Function

The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit (IPMU) is the primary flexor of the thigh with the ability to add and extra-rotate the coxofemoral joint. If the latter is fixed, the contraction of the iliopsoas muscle flexes the trunk and inclines it from the contraction side.[1]

The muscles can act separately. The iliacus muscle stabilizes the pelvis and allows a correct hip flexion during the run; the psoas major muscle stabilizes the lumbar spine during the sitting position and the thigh flexion in a supine position or when standing.[1] The psoas major acts as a stabilizer of the femoral head in the hip acetabulum in the first 15 degrees of movement. The psoas minor muscle participates in the flexion of the trunk and can stretch the iliac fascia.[1]

The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit consists of three muscles [1]: iliacus, psoas major, psoas minor

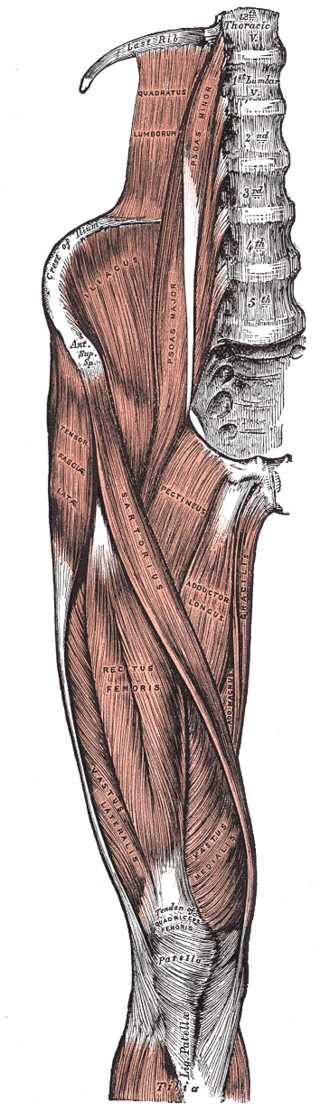

Anatomy

The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit is part of the inner muscles of the hip and forms part of the posterior abdominal wall, lying posteriorly at the retroperitoneum level.[2]

- The psoas major has a fusiform shape and originates from the transverse processes and the lateral surfaces of the bodies of the first four lumbar vertebrae; it involves the transverse process of the last thoracic vertebra and the vertebral body.[1] The path also involves intervertebral discs. The muscle bundles are directed downwards, parallel to the lumbar vertebrae, reaching the iliac fossa where there are the bundles of the iliac muscle. The bundles of the psoas major muscle and the iliac muscle join together, passing under the inguinal ligament. With a robust tendon, they insert onto the small trochanter of the femur. Generally, the right muscle size is greater than the left muscle.[2]

- The psoas minor muscle is located in front of the major psoas, originating from the last thoracic vertebra and the first lumbar; it is present in 60% to 65% of the population.[1] Distally, it converges with the iliac fascia and the psoas major tendon to insert onto the iliopectineal eminence (for 90% of the population).[1] This muscle should help the action of the iliopsoas muscle.

- The iliacus muscle has a fan shape and originates from the upper two-thirds of the iliac fossa and the lateral parts of the sacral bone wing. Its bundles (together with the major psoas muscle bundles) pass under the inguinal ligament and in front of the hip joint. The muscle bundles of the iliac muscle merge into the large psoas muscle tendon and the lesser trochanter. Small fibers that make the iliac muscle, known as the infratrochanteric muscle, lie lateral to the iliac muscle, widening its contact surface to the iliac bone.[1]

Below the tendinous unit is the iliopectineal bursa (aka iliopsoas bursa, which separates the tendon from the bone surface and the proximal portion of the femur.[1]

Fascia

The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit has many anatomical relationships through the fascial system surrounding it. Superiorly, the IPMU fascia merges with the chest fascia (endothoracic fascia) and posteriorly merges with the arcuate ligament of the diaphragm muscle.[2]

Anteriorly, the IPMU fascia merges with the fascia that covers the kidneys, the pancreas, the descending aorta, the inferior vena cava, the colon (ascending and descending), the duodenum, and the cecum colon.[2] Inferiorly, the IPMU fascia merges with the fascia lata of the thigh and the pelvic floor fascia; the fusion with the latter connects the psoas fascia with the fascial system of the abdominal muscles. Posteriorly, it merges with the fascia of the quadratus lumborum muscle.[2]

Embryology

There are no detailed studies on the embryological development of the muscles forming the iliopsoas. The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit (IPMU) is derived from the paraxial mesoderm.[3] After eight weeks of gestation and an embryo of 3 centimeters, the musculature is already formed.[3] Probably, the tendinous part that unites the three muscles that form IPMU develops within what will become the inguinal ligament.[4]

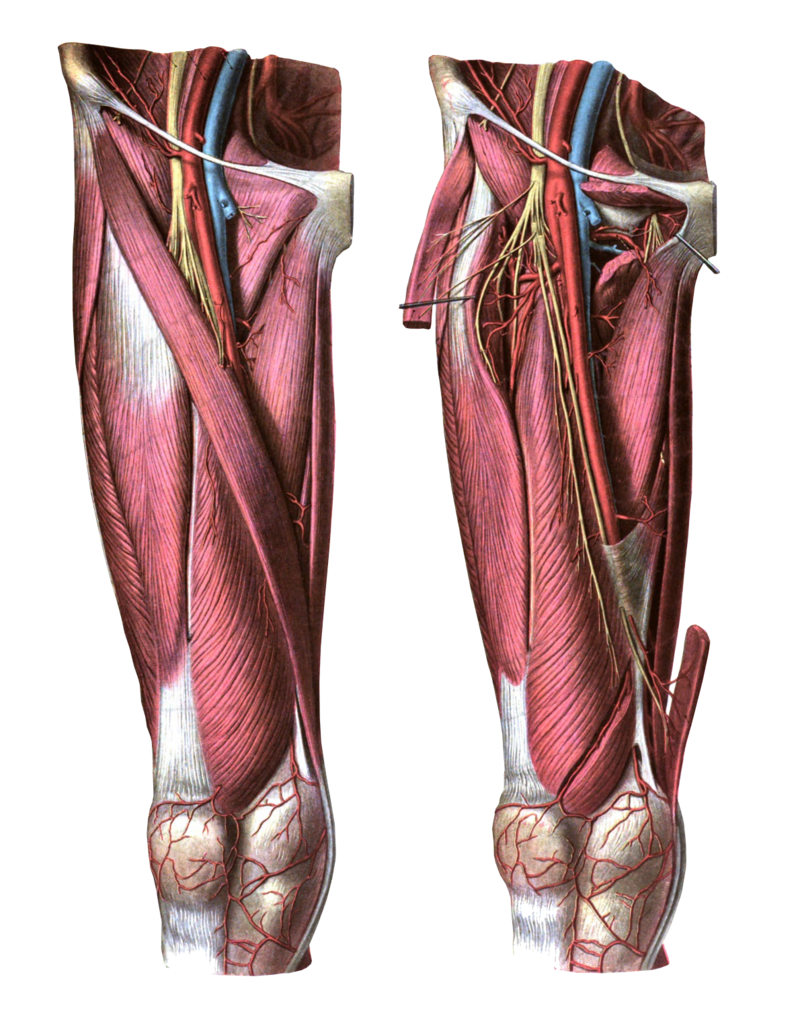

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The common iliac artery emits thin branches for the psoas major and minor muscle, while the most important artery for the blood supply of the muscle is the external iliac artery (born from the common iliac), which sends blood branches in its course to the iliacus muscle.[5]

The external iliac vein collects blood from the psoas major and minor muscles and the iliacus muscle; it is the continuation of the femoral vein.[5]

The lymphatic system that involves the iliopsoas muscle is the external iliac lymphatic plexus, which will merge into the common iliac plexus.[6]

Nerves

The short collateral branches of the lumbar plexus (L1-L3) innervate the psoas major and minor muscles, while the femoral nerve or terminal nerve of the lumbar plexus (L1-L4) innervates the iliacus muscle.[2]

Muscles

In a human model, the psoas major muscle fibers are mainly anaerobic or IIA fibers (about 60%), while the remainder is aerobic or type I fibers (about 40%).[7] Their distribution changes depending on the origin and insertion of the muscle. At the lumbar level (origin), one finds more red fibers, while at the hip joint, there are more white fibers. This means that at the lumbar level, its function is more static (posture), while it has a more dynamic function at the hip level.[7]

In an animal model, the aerobic and anaerobic fibers of the psoas minor muscle are similar in percentage.[8] Additionally, the percentage of predominant fibers in the iliacus muscle is of anaerobic or IIB type, with an increasing percentage towards the hip joint.[9]

Physiologic Variants

There are many anatomical variations of the iliopsoas muscle in the scientific literature.

- The iliopsoas tendon is the union between the psoas major muscle and the iliacus muscle; according to a recent review, there is a significant percentage of finding a bifid tendon (two tendons) at the level of the lesser trochanter of the femur (about 26%) unilaterally.[10] There is a very small percentage of cases with a bifid tendon bilaterally, as well as cases where the presence of three tendons is present.[10][11] As will be shown later, the tendon can be the site of pain and hip joint dysfunction. The psoas major muscle can have more muscle or accessory bodies, generally located on the left, innervated by lumbar branches.[12] The psoas major muscle can present itself with more fascicles but always belongs to only one muscle; it may have a tendon separate from the iliacus muscle or in connection with the quadratus lumborum muscle.[13]

- The psoas minor muscle is bilaterally absent for about 40% of the population.[1]

- There are anatomical variants for the iliacus muscle. In particular, on the left, there may be a supernumerary iliacus; it would start from the middle third of the iliac crest, separated from the main iliacus muscle but consistently innervated by the femoral nerve and with insertion together with the tendon of the iliopsoas complex.[12] An accessory muscle could originate from the iliolumbar ligament, traveling in front of the iliacus muscle and lateral to the psoas major muscle and finally merging into the muscle fibers of the iliopsoas complex; this accessory muscle is innervated by the femoral nerve and is called iliacus minimus muscle or iliocapsularis.[14] Its insertion could affect the proximal third of the femur or insert into the iliofemoral ligament.

- The innervation that affects the iliopsoas complex may present variations. The lumbar plexus and the femoral nerve normally pass behind the musculature of the psoas major. In some cases, the lumbar plexus can penetrate the psoas major muscle, giving the classic clinical symptoms of nerve entrapment.[15] The femoral nerve could cross the iliacus muscle.[16] An accessory muscle of the psoas major could cross the femoral nerve, dividing the nerve's path (splitting) and then traveling (the nerve) under the inguinal ligament normally.[17]

Surgical Considerations

Psoas Abscesses

The presence of an abscess in the psoas major muscle body is a rare event but needs aspiration. The causes are different, including the proximity to visceral and lymphatic structures, which can invade the muscle and infect the contractile structure.[18] Other predisposing factors are the presence of diabetes, intravenous use of drugs, renal failure, HIV, and a direct trauma with hematoma.[18] The presence of an abscess in the muscle can give clinical signs such as back pain, inguinal pain, pain in the hip, and fever; it is more common in men than in women. Generally, the infectious agents may be Staphylococcus aureus, streptococci, or Escherichia coli. A correct diagnosis requires computed tomography and blood tests; treatment requires abscess drainage and eventual cleaning of necrotic tissue and antibiotic therapy.[18]

Impingement of the Iliopsoas Tendon

Following an operation to replace the femoral head, the movement of the artificial head during hip extension may beat against the surrounding soft tissues, including the tendon of the iliopsoas complex. In this case, the surgeon may decide to review the space between the femoral head and the tendon.[19] In the event of complete replacement of the coxofemoral joint, an impingement of the iliopsoas and related pain and a functional decrease of the movement may occur in 4.3% of the interventions.[20] The causes can be a malpositioning of the prosthesis, protruding screws, or some cement debris. Excessive anteversion of the total hip acetabular component can result in anterior hip pain and/or patient-reported audible "snapping" or "popping" when the hip moves from flexion to extension.[21] Generally, a procedure in arthroscopy to release the tendon is well tolerated with few adverse effects.[22] The tendon may have impingement for tendon abnormalities or morphological changes of the coxofemoral joint, particularly at the upper lip of the hip joint capsule, with the presence of pain and functional decrease. Tendentially, there is conservative treatment, but in refractory cases, after three months of the conservative procedure, the doctor may decide to perform a surgical arthroscopic tenotomy.[23]

Iliopsoas Bursitis

Bursitis that involves the tendon of the iliopsoas complex is an inflammation that enlarges the volume of the bursa and produces pain on movement; its etiology is not entirely clarified. It can result from trauma, inflammatory arthritis, excessive use of the tendon in sports actions, or previous hip surgery.[24] The diagnosis is confirmed by ultrasonography, while for the resolution, the treatment is the aspiration of excess fluids with the introduction of corticosteroids and anesthetic.[24]

Other Surgical Motivations

In the pediatric population, in the presence of spasticity (cerebral palsy and other neurological diseases) and the presence of important contractures, surgery is performed with distal tenotomy.[10] This approach reduces the difficulty of walking and enables a posture that makes the child independent. The removal of muscle tumor masses is rarely done.

Clinical Significance

The iliopsoas muscle runs near different viscera; some pathologies affecting the muscle can simulate a disease of the internal organs. In the presence of a lesion of the right muscle, the pain is felt in the lower right quadrant, mimicking appendicitis. Hypertrophy of the muscle can prevent the correct passage of the fecal material of the colon. This may be responsible for compression of the femoral nerve and the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh at the level of the lacuna musculorum and the genitofemoral nerve at the level of the vessel’s lacuna gap (lacuna vasculorum), below the inguinal ligament.

It is difficult to diagnose a specific problem in the complex iliopsoas, but the following will demonstrate some evaluation procedures for identifying recurrent dysfunctions.

Iliopsoas Hematoma

A hematoma in the iliopsoas muscle could occur from direct trauma or a spontaneous hematoma. The latter could be caused by hemophilia, liver disease (cirrhosis), or errors in blood coagulation management (previous cardiac valve interventions).[25] Small underestimated trauma, muscle fibers not properly repaired after physical activity, and small vessels that break can also be causes. One of the symptoms is a sudden backache, not due to strain and pain in the flank (of the side of the muscle involved).[25] There may be a Grey Turner sign, which is ecchymosis visible on the flank, which results from a massive retroperitoneal hematoma, compression of the femoral nerve with thigh involvement, and muscular hypoesthesia of the leg can occur. To relieve pain, the patient assumes a flexion position of the leg while lying down. The surgical approach is only necessary if bleeding leads to dangerous complications for the patient's life (abdominal compartment syndrome, hypovolemic symptoms, and suffering of the femoral nerve).[25]

Iliopsoas Snapping

Iliopsoas snapping (IS) or coxa saltans is a dysfunction of the iliopsoas complex, which creates audible and palpable noise during active hip movements, with or without pain. There are three types of IS: external, internal, and intra-articular.[1] The iliotibial band causes the external type, and the gluteal maximus muscle tendon, which involves tendons moving above the great trochanter, creates noise and pain. The internal type involves the movement of the iliopsoas complex tendon over the anterior capsule of the femoral head, involving the iliopectineal eminence (muscle pulley) or the presence of exostoses of the small trochanter.[26] The intra-articular type is caused by moving internal bodies, labral tears, synovial chondromatosis, and the presence of chronic subluxation (dancers or children).[26] Other dysfunctions that cause this phenomenon (IS) could be linked to soft tissue abnormalities, the presence of an accessory strip of the psoas major muscle, a paralabral cyst, inflammation of the tendon, or bursitis.[1] Another cause is linked to the movement of the iliacus muscle/tendon against the pubic branch.[1]

After an accurate history (about 50% of IS occurs after a trauma to the hip) and a general palpatory inspection to highlight some anomalies, the active iliopsoas snapping test is performed. From the position of the Fabere test with the patient supine, the operator places his hand on the inguinal area. The patient returns the lower limb to a neutral position (abduction, external rotation, extension, and rest).[1] Generally, during palpation, you can feel or hear a typical noise (it may not happen), and pain is present, especially at 30 to 45 degrees of flexion.[1] For a differential diagnosis, you can do the bicycle test to understand if the cause is an IS of the external type, where the noise or an abnormal sliding movement is felt on the great trochanter.[1] The patient is in lateral decubitus, flexing and then actively extending the leg of the non-supporting side. To evaluate an intra-articular typology, the FADIR test is used where the supine patient actively performs flexion with the leg, an internal rotation, and adduction. This serves to identify an intra-articular lesion, such as a labral lesion.[26] Instrumental examinations can confirm the diagnosis. Radiographic assessment is performed to look for bone alterations, analysis with ultrasound and movement of the hip to research the extent of inflammation, and MRI for assessing intra-articular lesions.[1] Therapy is conservative.

Iliacus Muscle Hematoma

Hematoma of the iliacus muscle is an infrequent event. As with the psoas major muscle, hematoma could occur due to diseases related to blood coagulation, either hereditary or acquired.[27] It can occur after trauma or surgery, and the symptoms are pain in the groin and hip, pain in the abdomen, and weakness in the quadriceps muscle. There may be other symptoms, such as tachycardia, hypovolaemia, and a decrease in hematocrit values in severe cases.[27] The hematoma could cause neuropathy of the femoral nerve if the hemorrhagic extension is extensive, but this is rare.[27] As an instrumental examination to determine and validate the diagnosis, an abdominal CT is recommended; if the hemorrhage is not present and the hematoma is small, without giving neurological symptoms, the treatment is conservative.[27] In severe cases, the hematoma due to trauma or surgical approaches could cause paralysis of the femoral nerve.[28][29]

Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy

Using magnetic resonance imaging tests in patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, the iliopsoas muscle was shown to be (in 67% of patients) less involved in the disease, with a course of slower strength loss. The tone and size are maintained over time, but the patient cannot use the muscle well (neuromuscular coordination), particularly during walking. These characteristics are also found in other dystrophies (dystrophinopathy).

Groin Pain

Groin pain can result from iliopsoas tendinitis, which could derive from previous surgery or functional overloads. In the first case, an endoscopic iliopsoas tenotomy is generally recommended, while in the second case, it is advisable to reduce the muscle's workload.[30][31]

Other Issues

Conservative therapy for iliopsoas snapping includes physiotherapeutic procedures.

In the acute phase, the main approach is rest and anti-inflammatory drugs. When the treating clinician approves physiotherapy, several exercises will be demonstrated for the patient, including stretching the iliopsoas complex, active and passive hip joint mobilization, and exercises that improve the lumbar lordosis posture.[26] Muscle strengthening is required in the presence of a weakened muscle, not only of the psoas major muscle but also of all the muscles that participate in the movement of the hip, lower limb, and lumbar region. Exercises in front of the mirror to improve the quality of neuromotor intervention are recommended. Generally, following a rehabilitative path, in about 6 to 12 months, the motor function should be recovered without pain.[32][33]

The iliopsoas muscle could cause compression of the femoral nerve and cause knee pain. Before deciding on the surgical treatment to release the femoral nerve, the patient should learn stretching exercises to reduce the tension generated by the muscle. Generally, surgery can be avoided if the patient can follow the physiotherapy indications. According to the British Medical Acupuncture Society, an alternative treatment can be acupuncture for iliopsoas muscle, which has proved to be effective.

The osteopathic manual approach can intervene to support physiotherapy, particularly in the post-surgical phases, to reduce pain or act on deep muscle-articular areas with soft techniques and without side effects.[34]