Introduction

The scalene muscles are deep and positioned laterally to the cervical tract. Their innervation is complex, as both the brachial plexus and the cervical plexus are involved in their function. They are multi-articular muscles, and their actions are just as complex and vital. They play the role of accessory breathing muscles but are also important for the movement of the neck and the head and maintaining the posture between the neck and the head. Their dysfunction creates several pathological patterns, such as thoracic outlet syndrome, decreased ventilatory capacity, and cervical pain.

They are often the subject of medical approaches to diminish their tone and rehabilitative work to improve their physiological length or contractile strength. In this review, we will see how to apply stretching to the scalene muscles correctly and how to apply a manual differential diagnosis between the latter and the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Structure and Function

The scalene muscles are involved in lifting the first two ribs in a forced inspiratory act as secondary respiratory muscles. In reality, the scalene muscles are always electrically active, even for not necessarily forced breaths. The scalene muscles, when not engaged as respiratory muscles are very active in the supine position and with the arm raised. They act as postural muscles in maintaining the position of the cervical tract or playing an active role in the movements of the neck. They can incline the neck and intervene in the first degrees of rotation of the head. A bilateral contraction of the scalene allows a neck flexion.

There is a close relationship between the intercostal muscle afferents (between the eighth and tenth ribs, anteriorly). Their unilateral stimulation activates the scalene muscles bilaterally. The connection is not completely understood. Probably, an inspiration that requires the intervention of the lower ribs would stimulate the scalene muscles as an aid to breathing.

Anatomy

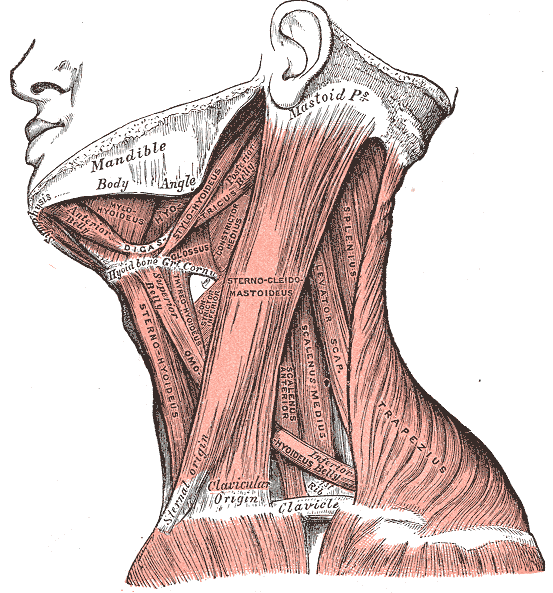

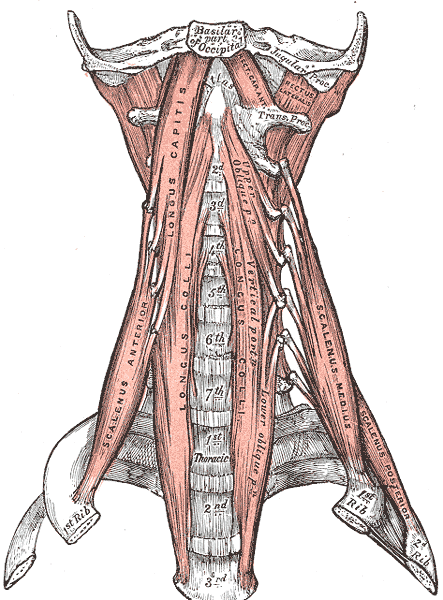

The scalene muscles are located deep in relation to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, lateral to the cervical spine, connecting the vertebrae to the first two ribs. The deep fascia or prevertebral fascia envelop the scalene muscles.

- The anterior scalene originates from the anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae, from the third to the sixth vertebrae. It is inserted into the scalene muscle tubercle of the upper face of the first rib. Some fibers of the anterior scalene can touch the pleural dome. The muscle omohyoideus passes over the anterior and middle scalene. The muscle is thicker at the level of the cricoid cartilage and is thinner at the origin and insertion level. The phrenic nerve passes over and shares the fascia of the muscle from the lateral border to the medial border, behind the subclavian vein. The anterior and medial scalene muscles form the space (fissura scalenorum) for brachial plexus passage.

- The middle scalene originates from the transverse processes of the last six cervical vertebrae, between the anterior and posterior tubercle, inserting itself on the upper face of the first rib, posterior to the sulcus of the subclavian artery. The upper portion of the long thoracic nerve passes between the middle and posterior scalene or passes through the middle scalene or above the latter.

- The posterior scalene muscle originates from the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the last three or four cervical vertebrae. It fits on the anterior face of the second rib.

In about 30% to 71% of the population, there is the fourth scalene or minimum scalene, affecting the anterior tubercle of the transverse process of the seventh cervical vertebra, to insert itself on the first rib and the Sibson’s fascia posteriorly, which covers the pleural dome. The minimum scalene can be confused with the transverse pleural ligament.

Embryology

The scalene muscles derive from the myoblasts of the hypaxial portion of the cervical myotomes, together with the prevertebral muscles and the geniohyoid muscle in the seventh week of gestation of the embryo. The muscular formation pattern is controlled by the connective tissue in which myoblasts migrate. The cervical area of the connective tissue differs from the somitic mesoderm.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Its origin derives from and is recognized by the first portion of the subclavian artery, defined as a pre-scalene area. The thyrocervical trunk passes near the anterior scalene muscular district. It is directed upward to divide into two terminal branches. The first terminal branch or inferior thyroid artery carries blood nourishment to the anterior scalene muscle. The second terminal branch, known as the ascending or superficial cervical artery, directs the blood flow to medium scalene and posterior scalene.[1][2]

- The venous trunk responsible for draining blood from the scalene muscles is the brachiocephalic venous trunk. The latter derives from a branch known as the vertebral vein.

- In the region of the cervical tract, there are about 300 lymphatic nodes. Those responsible for draining the lymph from the scalene muscles are always located in the back triangle of the neck. The drained lymph arrives in the jugular lymphatic trunks found both right and left. Further, the right lymph will flow into the right lymphatic duct, while the lymph collected in the left portion will end in the thoracic duct.

Nerves

The scalene muscles are innervated by the anterior branches of the cervical spinal nerves from C3 to C8. Scalene muscles involve the cervical plexus and the brachial plexus; the collaboration between the two complexes is fundamental for the different functions of these muscles. There are variants in neuroanatomy surrounding the scalene, but these are rare.[3]

Muscles

The fascial continuity that is part of the biotensegrity model prevents any muscle from acting alone—every muscle action results from the cooperation of all the neighboring muscles. Every muscle knows the muscular tension of the neighboring districts.

The deep muscles such as the rectus capitis anterior and lateralis, the cervical and brachial plexus innervate the capitis and longus colli muscles. It is extremely difficult not to meet a scalene problem without dysfunction of other deep muscles of the neck; the inability to extend the head is synonymous with a general dysfunction of these muscles and scalene muscles.

Physiologic Variants

Scalene muscles, like any other anatomic district, possess various anatomical variables.

- The anterior scalene muscle could originate from C2 and/or not involve C6. Insertion of the muscle could involve not only the first rib but also the second or third thoracic rib. The anterior scalene muscle could pass behind the subclavian artery, either homolaterally or bilaterally (right and left). Furthermore, it could be found behind the first thoracic nerve. In some cases in the literature, the anterior scalene muscle is absent, both on one side and bilaterally.

- The middle scalene muscle could deviate in its insertion into the transverse processes of the atlas cervical vertebra, leaning in its final path on the second thoracic rib. In some scientific articles, an accessory middle scalene muscle is identified, which builds a bridge with the anterior scalene muscle. This anatomical variant could cause a symptomatic picture that refers to the thoracic outlet syndrome.

- The posterior scalene muscle could involve the cervical vertebrae from C3 to C7; some of its fibers can create a single muscle structure with the middle scalene or the first intercostal muscle. Its final insertion could touch the third thoracic rib. In some subjects, this muscle may be absent. The middle scalene could be perforated by branches of the brachial plexus, such as C7 and C8, which will terminate on the posterior scalene muscle. Some authors have found that posterior scalene muscle could have a double layer, with a ventral area and a dorsal portion.

- The minimum scalene may arise flattened and involve a large area of the thoracic outlet. This muscle, in its origin, could involve C6 and C7 vertebrae.

Surgical Considerations

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) occurs secondary to direct or indirect mechanical compression of the subclavian vessels and/or the brachial plexus between the clavicle, scalene muscles, and the first rib. The most common presenting clinical symptoms include fatigue, pain, and paresthesias affecting the upper extremity. Dynamic, postural-based symptoms can often make the diagnosis somewhat challenging. The latter occurs secondary to neurovascular compression and when the upper extremity is brought to increasing levels of overhead elevation. TOS can be suspected in patients reporting the aforementioned symptoms, and further suggestions of TOS as a diagnosis include the presence of a cervical rib (0.5% of the population).[4]

There have been case reports of various forms of TOS occurring secondary to a hypertrophic anterior scalene muscle.[5] In some cases, it is necessary to eliminate the scalene, either the anterior or middle (i.e., a scalenectomy) muscles. In the presence of abnormal muscle bundles that can compress the vascular-nervous brachial package, identified with ultrasound ("wedge-sickle sign"), the patient must undergo muscular resection. In certain situations when the pathology is secondary to the scalene muscle itself, symptoms can be acutely managed with type A botulinum toxin (botox) injections. These are also helpful in older patients that may need to delay surgery.[6] In specific situations of spasmodic torticollis or cervical dystonia, botox injections can help mitigate symptoms as well.

Neck Mass Dissections

Tumor formation can form within the scalene muscle; one particular type is known as myopericytoma. This tumor is very rare, and it is often necessary to remove it surgically. Surgical dissection for tumor/mass removal includes intramuscular dissection to either marginally or radically resects the tumor bed. Another example of a tumor is myxoma, a rare mesenchymal tumor of the head and neck. More frequently, benign tumors are found, such as fibromatosis within the muscle, which also is often surgically removed. You can perform biopsies on the lymph nodes of the scalene muscles to check the type of tumor. In some cases, splenectomies can be performed to create space for extracting deeper tumors, such as a cervical schwannoma. Finally, mass effects can occur secondary to direct trauma with a resultant intramuscular hemangioma.

Nerve Blocks and Catheter Considerations

Nerve blocks and nerve catheters are becoming increasingly important as the healthcare system continues to shift toward more outpatient-based procedures.[7] The indications for nerve blocks vary, some of which include improving neurological pain or depressive-type syndromes. The literature supports a continuous interscalene over a single-injection block because of lower rates of toxicity and lower reported levels of symptomatic rebound once the anesthetic wears off.[8][9] Another invasive intervention is the pharmacological block of the stellate ganglion, in which a needle passes through different tissues, including the anterior and middle scalene.

Clinical Significance

Instrumental Evaluation

To evaluate the function of the scalene muscles, electromyography can be used to identify contractile anomalies. This can use sonography or ultrasound, as well as other more expensive instruments, such as magnetic resonance and CT scans.

To assess whether vascular compromise exists, there are no valid manual tests to identify the compromised area or determine if the cause is arterial or venous. Only an examination with an echo-color doppler can make a vascular diagnosis on a scalene level.

Electromyography can be used in suspected thoracic outlet syndrome and other clinical settings. In patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction, it has been shown that anterior scalene has greater electrical activity than people without mandibular joint problems. This could be useful information for the physiotherapist or the osteopath. We know that a dysfunction of the scalene muscles reduces the ventilatory capacity of the patients, and a mandibular disorder could be a symptom rather than the cause.

Manual Assessment of Scalene Muscles

Palpation is a valuable tool used to evaluate, classify, and make a diagnosis. The fingertip's tactile sensitivity can be used to evaluate objects measured in microns. Clinicians can use palpation to determine the position of the joints and recognize abnormal joint movements, tissue abnormalities, including temperature, tone, and hardness on the surface and deep in the various layers, and identify painful areas.

From an osteopathic point of view, tissue injury always creates a “mnemonic tattoo.” This immediately allows clinicians to understand, at the touch, the direction of the tissue toward the primary lesion. This lesional tattoo is the changed morphology of the cells, as well as their preferential vector, the altered behavior using the pressure from being touched.

According to literature, when palpating to verify the status of the scalene muscles, it is necessary to ask the patient to laterally flex the neck, with the direction opposite to our fingers; touch to the right with the neck flexion to the left. In this way, the scalene muscles are put in tension, and it is easier to palpate them.

The scalene musculature (including the posterior scalene) can fatigue during a repeated respiratory effort, particularly in patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These contractile districts are often over-stimulated and hypertonic compared to those in comparison with healthy subjects.

To evaluate tone and the tissutal quality of the scalene muscles, the examiner must position himself behind the patient, who is supine (better) or seated. With one hand, they hold and control the patient's nape, while with the other hand, he tries to prevent the first thoracic rib from rising, supporting the eminence hypothenar in the anatomical area of the supraclavicular fossa. This last position is necessary to prevent the first rib from moving during neck movement and prevent an incorrect tension of the muscles.

- For the anterior scalene, the patient's head tilts to the left and simultaneously turns to the right side. (See photo 1)

- For the middle scalene, the head bends to the left without rotations, respecting the functional anatomy (See photo 2). The hand placed on the rib is useful when the stretching of the muscle involves the insertion area, with an additional passive movement of the head. The abnormal tension in the muscle and often painful, induced movements will result in a reduced excursion. Tension and pain in the anterior and middle scalene muscles can be frequent causes of thoracic outlet syndrome.

- For the posterior scalene, preventing the elevation of the first rib, slightly incline the neck while trying to rotate the head to the left.

Stretching exercises can be performed with the same positions used for assessing any restrictions on each portion of the scalene muscles. The exercise must be performed in the presence of an operator because the patient cannot understand the movement of the first rib during the small movements allowed by each scalene muscle.

To differentiate a problem of the scalene muscles from a dysfunction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), an operator positions himself behind the patient (sitting or standing). The operator places his hands on the patient's shoulders and asks for a deep inhalation, preventing the movement of the shoulders. In this way, the intervention of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is excluded, and the elevation of the first ribs is allowed. If the scalene musculature is painful or has some restrictions, the problems of the scalene muscles will be highlighted. On the contrary, to focus attention on SCM, the elevation of the first ribs is prevented by resting the thumbs during a forced inhalation.

Clinical Implications

An increase in tone or thickness of the anterior scalene muscle may result in distant symptoms. Vascular compression of the subclavian artery would give pallor and cold sensation to the extremities, cyanosis, and difficulty using the arm. If C5-C6 crosses the muscle in non-physiological conditions (hypertrophy, shortening), it could cause paresthesia, anesthesia, or weakness of the muscles innervated by these roots. If the root of C8 runs back to the two attacks, the anterior scalene, and there is a squeeze, there may be symptoms such as tingling, pain, and weakness of the hand and the interosseous muscles. If the anterior scalene tendon mixes with the longus capitis muscle, headaches may occur.

- If the suprascapular nerve passes through the middle scalene (hypertonic and hypertrophic, shortened), symptoms such as weakness of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle may occur, with paresthesia and pain in the shoulder and scapular area and subsequent alteration of the arthrokinematics of the scapulohumeral joint. If the deep branch of the transverse cervical artery passes through the muscle, it could cause nuanced symptomatology or difficulty in identifying the problem.

- An increase in thickness of the posterior scalene muscle could alter the course of the long thoracic nerve and the scapular dorsal nerve, with pain or weakness in the anterior serratus muscle, the scapula elevator, and the rhomboid muscles.

- The presence of minimum scalene may reduce the brachial plexus passage space and the passage of the subclavian artery and the subclavian vein, causing symptoms related to thoracic outlet syndrome.[10]

Other Issues

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

In patients with COPD, the diaphragm muscle is weakened, flattened, and during the inhalation position, it forces the accessory respiratory muscles to intervene with greater emphasis. What happens to the scalene muscles? An inverse relationship between the thickness of the diaphragm muscle and the thickness of the scalene muscles has been demonstrated: the decreased thickness of the diaphragm and increased hypertrophy of the scalene muscles. Generally, the latter is rich in red or aerobic fibers, but if subjected to constant work, bearing a greater load, the red fibers increase their mass, both as proteins and as quantities of mitochondria and enzymes, capillaries. COPD is an aggravating disease, and the scalene muscles increase the tone and volume not only for hypertrophy but the chronic shortening of the muscles themselves. The first ribs are in an inspiratory attitude, with the pulmonary dome in constant tension. During inspiration, the dome will have difficulty moving downward, further complicating the respiratory act by decreasing the pulmonary vital capacity.

It has been shown that a postural attitude of the neck, where the head is held forward, reduces lung vital capacity for the same mechanisms described above of the scalene muscles: shortening and increased tone. This happens independent of the presence of respiratory diseases.

A valid approach to reducing non-physiological adaptation of the lung due to scalene muscles in shortening is stretching, as shown by clinical research.

Myofascial Pain

Scalene muscles can be a source of pain. On the one side, muscle mass can present trigger points and painful differences. On the other side, the same connective tissue that covers and connects the muscle, the fascia that connects the muscle with other muscles, viscera, and joints, can present as painful anomalies. The scalene muscles can cause a sore cervical tract. Pain can easily be located or cause more distant symptoms, such as migraines.

These fascial anomalies or alterations of the contractile tissue can occur in the absence of traumas, such as erroneous daily attitudes, or traumas such as whiplash, or due to the presence of diseases that alter the thoracic conformation such as scoliosis, which can cause a non-physiological cervical biomechanical environment.

This constant pain can reduce lung vital capacity. Studies show that an approach with breathing exercises that re-educate the scalene muscles helps decrease or eliminate the pain experienced by the patient.

Another approach to reducing myofascial pain is osteopathy, with indirect or fascial techniques. Several studies show how these gentle techniques can reduce local pain with systemic involvement. The blood values of the inflammatory indices are lowered, and the activity of the sympathetic system is lowered.

Other more recent approaches demonstrated in the literature are dry needle therapy or taping by physiotherapists. The mechanisms of action of these last two therapeutic approaches are not well understood, despite the positive results.

Anti-inflammatory drugs do not solve the structural abnormalities but only treat the symptoms. Once the analgesic effect ends, there is a high chance that the pain will return.

In subjects exhibiting a posture with a forward head position, they demonstrate a greater pain sensitivity, particularly for the trapezius and the scalenus medius; these muscles also demonstrate less range of motion in such cases.[11] Probably, a manual approach to improve the functional capacity of the scalenus medius (and trapezius) could improve the daily posture of the head and neck. The presence of a forward head posture could be related to cervicogenic headache pain.[12]