Continuing Education Activity

Vulvodynia is a vulvar pain of at least three months' duration without a clear identifiable cause. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and is considered an idiopathic pain disorder. Vulvodynia can cause pain that is severe, debilitating, and devastating to the patients suffering from it. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of vulvodynia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients suffering from this condition.

Objectives:

- Review risk factors for the development of vulvodynia.

- Describe the typical findings associated with vulvodynia.

- Summarize common complications of vulvodynia.

- Explain the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to improve outcomes for patients with vulvodynia.

Introduction

The current International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) definition of vulvodynia is a vulvar pain of at least three months' duration, without a clear, identifiable cause, which may have potential associated factors. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and is an idiopathic pain disorder.

Etiology

The cause of vulvodynia is not known. Research is being done to learn what contributes to the condition. Possible contributing causes include injury or irritation to the nerves that transmit pain from the vulva to the spinal cord, an increase in the number and sensitivity of nerve fibers in the vulva, elevated levels of inflammatory substances including cytokines in the vulva, abnormal response to environmental factors, genetic susceptibility, and pelvic floor muscle weakness, spasm or instability. [1]

Epidemiology

The annual incidence cited by Reed was 3.1% in 2012. In 2014, the incidence was 4.2 cases per 100 woman-years and differed by age, ethnicity, and marital status. Independent NIH-funded population-based studies by Harlow, 2003; Reed 2004 and 2006; and Arnold, 2007 demonstrated a point prevalence of 3% to 7% in reproductive-aged women. Three of the studies included clinical confirmation components. According to Harlow, 7% of American women will have symptoms consistent with vulvodynia by age 40. Interestingly, only 1.4% of women seeking medical care were correctly diagnosed. [2]

Pathophysiology

The anatomy of the vulva and vulvar vestibule is very important to understand vulvodynia.

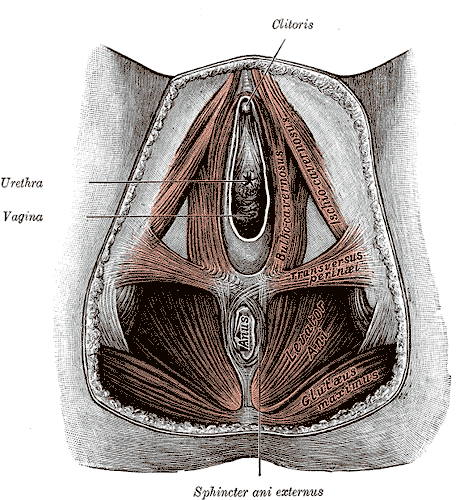

The vulva and vulvar vestibule: the vulva is the external female genitalia, which includes the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoral hood, clitoris, and vestibule. The vulva is innervated by the anterior labial branches of the ilioinguinal nerve, genitofemoral nerve, and branches of the pudendal nerves. The pudendal nerve divides into three branches near the medial aspect of the ischial tuberosity: (1) the dorsal nerve of the clitoris, (2) the perineal nerve which innervates the labia majora and perineum, and (3) the inferior rectal nerve which innervates the perianal area. The pudendal nerve also innervates the external anal sphincter and deep muscles of the urogenital triangle.

The pelvic floor muscles are divided into three categories:

- The superficial pelvic floor muscles (bulbocavernosus, ischiocavernosus, and superficial transverse perineal muscle) are collectively known as the urogenital diaphragm. These muscles control sexual function, e.g., clitoral engorgement, vaginal closure, and reflexive response to enhance sexual pleasure, and facilitate closure of the urethra and anus for continence.

- The middle layer consists of the sphincter urethra and deep, transverse perineal muscle.

- The deep pelvic floor muscles are sometimes called the anal triangle. They are the levator ani (pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and puborectalis) and coccygeus. The piriformis, obturator internus muscles and the gluteus maximus are associated pelvic and hip muscles. The perineal body is the central tendon and attachment site for the pelvic floor muscles. These muscles support the abdominal viscera, provide pelvic and spinal stability, assist in respiration, provide sphincteric closure for bowel and bladder, and have a role in sexual function.

The internal pudendal artery, vein, and nerve pass through the Alcock canal and provide a neurovascular function for the pelvic floor musculature.

Toxicokinetics

Vulvodynia is a vulvar pain of at least three months' duration without a clear, identifiable cause. It may be generalized or localized with respect to location. It may always occur spontaneously or have to be provoked. It could occur throughout a patient's life or just with a new partner (primary or secondary) and/or it can be intermittent, persistent, constant, immediate, or delayed in timing. [3]

Other diagnoses must be ruled out, such as:

- Infections: vulvovaginal candidiasis, trichomoniasis, and genital herpes

- Inflammation: lichen sclerosis, lichen planus, contact dermatitis, lichen simplex

- Neoplastic disorders: squamous cell carcinoma

- Neurologic disorders: pudendal, genitofemoral and/or ilioinguinal nerve injury, nerve entrapment, neuropathy, Tarlov cysts

- Vulva trauma, leading to pain: straddle injuries, female genital cutting, motor vehicle accidents

- Estrogen deficiencies

- Iatrogenic causes

History and Physical

The patient should undergo a thorough gynecologic examination. Once all infectious, inflammatory, hormonal, neoplastic, and neurologic causes are investigated and treated, a visual inspection of the vulva and vulvar vestibule should be performed. [1]

- Cotton swab evaluation: Ask the patient, "Where does it hurt?" and, "Does it hurt before I even touch you?" From the outside in towards the vestibule, mark the area to find the location of the pain. Starting from the inner thigh, move to labia majora, inner labial sulcus, clitoris, and clitoral hood, perineum, and sites within the vestibule. The patient should rate their pain on a scale of 1 to 10.

- Neurosensory: Cotton versus pinprick exam in the same places - note whether it is normal, hyposensitive, sharp, burning, or shooting pain.

- Pelvic muscle exam: Starting with puborectalis and working way into the pelvic muscles.

- Evaluation of pain comorbidity: Interstitial cystitis, endometriosis, temporomandibular joint syndrome, chronic headaches.

- Assessment of factors contributing to pain: Emotional functioning, sleep interference, relationship problems, physical functioning, sexual functioning

Evaluation

There are no blood tests necessary. A thorough history and physical with medication and drug allergy review should be performed.

Treatment / Management

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary treatment approach. It is important to believe that the woman has pain. In many cases, the woman has been struggling for a long time in silence, or she has seen many practitioners, and no one has helped her. Different practitioners may be involved in the care of this patient. When a patient finds the correct practitioners, they may include a gynecologist with a special interest in vulvovaginal disease health usually involved in the societies ISSWSH and ISSVD, a dermatologist, a neurologist, a pain management specialist, a urologist, and/or a physical therapist who specializes in women's health. [4]

Treatment Modalities

- Vulvar self-care: Avoid irritants, directly or through diet

- Oral "pain-blocking" medications: These may be effective in alleviating vulvodynia pain. The classes of drugs are tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and anticonvulsants. The TCAs are used most often, and the most commonly used among them are amitriptyline and nortriptyline. Because nortriptyline has fewer side effects, it is usually the first choice. The dose is lower than that which is used to treat depression. Due to side effects, it is suggested to begin with very low doses and increase gradually. The more commonly used SNRIs are duloxetine and venlafaxine, and the anticonvulsants typically used are gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate.

- Topical medications applied directly to the vulva can alleviate pain as long as there are no allergens in the ointments. These are usually compounded. Examples combined or used alone are lidocaine, estrogen, testosterone, and gabapentin.

- Women's health physical therapy has become an effective addition to the treatment of vulvodynia. Most patients should be referred for evaluation and treatment of pelvic floor muscle weakness and spasm. Treatment includes exercises, massage, soft tissue work, and joint mobilization.

- Nerve block, psychotherapy, mindfulness, yoga, and neurostimulation are also helpful in treatment.

- Surgery is reserved for specific patients. It is for provoked vestibular vulvodynia. Vaginal advancement involves removing the vestibule and the involved area of the vagina. Physical therapy and the use of dilators after therapy are recommended.

Differential Diagnosis

- Vulvar burning or irritation

Pearls and Other Issues

Research on the topic of vulvodynia is ongoing. Twenty-five percent of adult Americans suffer from a chronic pain condition. Patients in pain are often neglected and under-treated. This pain condition is severe and debilitating and can be devastating to the patients suffering from it. The scientific level of evidence for almost all treatment regimens is poor, with very few randomized controlled trials having been performed. Treatment outcomes vary in the studies we have, but the majority of women improve with treatment. Practitioners should be encouraged to take their patients seriously and remember that this condition exists. If the practitioner is uncomfortable treating the condition or does not have the education and experience to treat the condition, they should query the National Vulvodynia Association and find a practitioner who does.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The cause of vulvodynia remains unknown and hence its treatment remains unsatisfactory. Treatment requires an interprofessional treatment approach. It is important to believe that the woman has pain. In many cases, the woman has been struggling for a long time in silence, or she has seen many practitioners and no one has helped her. Different practitioners may be involved in the care of this patient. When a patient finds the correct practitioners they may include a gynecologist with a special interest in vulvovaginal disease health usually involved in the societies International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and ISSVD, a dermatologist, nurse practitioner, a neurologist, a pain management specialist, a urologist, and/or a physical therapist who specializes in women's health. [4] Unfortunately, despite adequate treatment, the pain is recurrent and seriously affects lifestyle and interpersonal relationships. [5][6] [Level 5]