Definition/Introduction

Buoyancy while scuba diving, snorkeling, or swimming is a safety skill. It also has multiple medical and diving implications. A diver’s air consumption and fatigue are strongly correlated with their buoyancy control. Ascent and descent in a water column (whether salt or fresh) when controlled, protects the diver from barotrauma of both sinus and middle ears, pulmonary hyperinflation, air embolism, and reduces the risk of decompression sickness. Buoyancy control also affects and protects both the diver and the marine environment.

Pressure changes and the need for equalization occur primarily in the first 33 feet [10 meters (m)] of water consistent with Boyle’s Law. If a diver can master pressure changes in the first 66 feet (20 m) of depth, the incidence of dive related injuries is significantly reduced. Most recreational diving occurs in this range because of light penetration from the surface and visibility. Beyond 66 feet (20 m), the changes are minimal, and the diver must rely on their equipment to determine their depth and rate of descent or ascent.

Uncontrolled descent from being overweight, from equipment malfunction, or from environmental conditions can result in disorientation, panic, tympanic membrane rupture, sinus squeeze, drowning, physical trauma, nitrogen narcosis, and loss of visibility from stirring up bottom debris. In caves or wrecks, buoyancy is essential to avoid entrapment, directional, and spatial disorientation.

Uncontrolled ascent in an underweighted diver or low/out of air situations can result in discomfort, a reverse sinus block, middle ear barotrauma, pulmonary hyperinflation becoming pulmonary barotrauma, and air embolism when the breath is held. Decompression sickness can occur from sudden expansion or destabilization of nitrogen bubbles in the bloodstream. The uncontrolled ascending diver can also either strike or be struck by objects on the surface such as boats and other passing watercraft.

Assessment and treatment of patients with buoyancy related problems involve not only understanding when the injury occurred during the dive but also how to intervene to reverse the causative process. [1]

Issues of Concern

Good buoyancy control is an essential element in proper gas management, and depth control is only one part of this solution. Fewer adjustments to buoyancy reduce consumption of air, as does reduced effort from the ability to obtain a streamlined hydrodynamic attitude. Any decrease in a diver's effort at depth can lessen decompression stress, and good buoyancy goes dramatically helps to achieve that goal. As a cinematographer, video and still images are stable underwater when neutrally buoyant, and in a cave or wreck contact with the surfaces are minimized reducing injury and maintaining visibility.

Gear Basics for Buoyancy

The Buoyancy Control Device (BCD) or Jacket, thermal protection, lead shot or weights integrated into the jacket or on a belt, and the diver’s lungs are the primary equipment involved in personal buoyancy control.

Intrinsic Factors

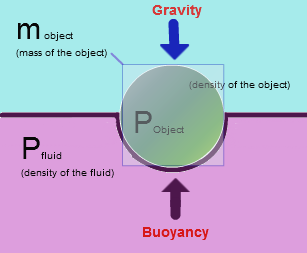

According to Archimedes principle, if a swimmer remains still on the water they displace an equal amount of their volume in the water itself. Their upward buoyant force must exceed the downward gravitational force to float.When salt is dissolved in water, its density increases as does its buoyant force. Most swimmers that are still in freshwater and exhale have negative buoyancy and sink. Ocean water has a salinity of approximately 35 parts per thousand (ppt). In contrast, the Dead Sea has 337 ppt, making a human’s ability to sink there nearly impossible. Therefore, water salinity has the greatest external impact on positive buoyancy.

Internal factors in the human body that affect buoyancy are percent body fat as well as lung and gastrointestinal gas. The volume of air in the gastrointestinal tract, sinuses, and middle ear while small can strongly influence the risk of barotrauma but has little influence on buoyancy. Similarly high body fat also has a small positive effect on buoyancy. For example, to be neutrally buoyant in freshwater a human must have 60% body fat (i.e., a 131 kg man, 157 cm tall with a 132 cm waist). Body fat percent may be an important factor for snorkelers that require some lead weight to descend. Lung volume, however, has the greatest self-generated effect on buoyancy. When neutral, the diver can fine-tune their buoyancy with their breath. To descend, they exhale, ascend by inhaling, or take partial breaths to stay neutral.

Thermal Protection and Buoyancy

Beyond salinity, thermal protection has the greatest influence on a diver’s positive buoyancy. A dive skin made of nylon, lycra, spandex, or other material are neutrally buoyant. These, however, are impractical in cold water. The degree of positive buoyancy is determined by whether the diver wears 3 millimeters (mm), 5 mm, 7 mm wetsuit, or a dry suit. A dry suit typically requires slightly more additional lead weight than a 7 mm wetsuit to compensate for air added to the suit during a dive to avoid a suit squeeze, usually 3 pounds (1.36 kg).

Tanks and Lead

Scuba tanks vary in their buoyancy based on their material. An Aluminum 80 cu ft (12 L) tank is 1.6 pounds negative when full (0.72 kg) and 2.8 pounds positive with 500 psi (1.28 kg at 50 bar). A 12 L steel tank is about 9 pounds (4 kg) negative full and three pounds (1.36 kg) negative empty.

The rule of thumb for lead weight to counteract the positive buoyancy of a wetsuit is 2 to 3 lb (1 to 1.36 kg) of buoyancy per mm of neoprene. To counteract the positive buoyancy of a BCD, a diver may need up to four pounds of lead (two kilos) depending on the BCD.

A ballpark figure for the amount of lead needed for a diver in full scuba gear is ten percent of their body weight when wearing a 7 mm wetsuit. Finally, the average difference in lead requirement going from fresh to ocean, saltwater diving warrants adding 4 to 7 pounds (2 to 3.5 kg) of lead to the diver.

There is no difference between solid lead nor lead shot regarding its affect on buoyancy. The latter is typically in a bag and has the advantage of possibly reducing the severity of injury when dropped. It also is more malleable when placed in an integrated pouch, in a BCD, or between tanks. All lead attachment systems require a quick release for an emergency ascent. Lead is preferred for diving due its high density, ease of casting, corrosion resistance, and low cost. The author made his first lead weights by melting down tire balancing lead (collected for free) in a high school metal shop and pouring them into ingots.

Buoyancy Control Device: History and Mechanics

The BCD has a long history and developed over time from a horse collar to the current jacket. It appeared approximately twenty years after Jacques Cousteau launched the aqualung. In 1961, Maurice Fenzy designed the horse collar or Adjustable Buoyancy Life Jacket that was inflated by mouth. In 1968, Joe Schuch and Jack Schammel developed a buoyancy compensator vest that featured a smaller buoyancy ring behind the diver's head, and a midriff section with volume to lift the diver's head out of the water if one or both of its carbon dioxide (CO2) cartridges were activated for an emergency ascent. In 1972, Watergill developed the first wing style jacket with cummerbund, shoulder straps, inflator, and an integrated weight system. Minor changes and variations on the BCD developed since.

Prior to the BCD, divers had to add their lead very accurately so that they would be slightly negative at the beginning of the dive and slightly positive at the end of the dive. While this remains the goal even with a BCD, the diver can add air to a BCD as needed to compensate and even lift heavy objects from the seabed (up to 60 pounds or 27 kg) by adding up to 30 L of air. Separate lift bags, however, are recommended when lifting objects from the deep.

Nowadays, air can be added to a BCD in three ways, by mouth, by an inflator hose connected to the regulator, or via a carbon dioxide cartridge (one time use). During training, divers are taught to add or release air to the BCD in small increments and wait for their buoyancy to adjust before making additional changes. This avoids uncontrolled ascent or descent.

Neutral Buoyancy Summation

The goal of these combined systems is to obtain neutral buoyancy which maximizes the diver’s trim. Trim is the diver's attitude in the water, in terms of balance with the direction of motion. Accurately controlled trim decreases swimming effort, as it reduces the sectional area of the diver as they pass through the water. A slight head down trim is the best position to reduce down thrust during finning, and this reduces silting and fin impact with the bottom. It also allows the diver to look down comfortably. A stable horizontal trim requires that the diver's center of gravity to be directly below the center of buoyancy (the centroid).

On the surface with a full tank of air, a diver can adjust their lead so that when their BCD is fully deflated and they have a half breath of air, they float at eye level in the water. This is the standard for initial assessment of neutral buoyancy. As they make their descent, their neoprene, and the residual air in their BCD is further compressed. They may then need to add air via filling their lungs or adding air to their BCD to once again achieve neutral buoyancy at depth. On ascent, the release of BCD air and a long slow exhalation is needed as the air expands (according to Boyle’s law) to control buoyancy, lung inflation, and rate of ascent.

Other advantages of neutral buoyancy maintenance include reduced energy expenditure, reduced decompression stress, better gas management, and a sense of freedom and weightlessness without free fall. The diver can hover upside down and peer into crevices and holes without fear of striking the bottom. They can lie on their back in the water column without sinking to spy surface marine creatures and boats. Most importantly they can relax, and focus on work or simple enjoyment while minimizing environmental impact. [1]

Clinical Significance

To understand the unique injury pattern during a dive related to buoyancy problems, the practitioner needs to determine when in the dive the injury occurred to diagnose the problem better. To that end, we will discuss each phase of a dive and the potential injuries unique or common to uncontrolled buoyancy during those events.

Uncontrolled descent can occur because of being overweighted, unprepared (e.g., no fins), having equipment malfunction (e.g., BCD leak and flooding), or poor environmental conditions (e.g., down currents and rip tides). Most of these can be prevented on the surface through careful preparation and equipment checks by both the diver and their dive buddy.

Equalization and Barotrauma

The pressure difference between a head up and head down position on the surface is sufficient to result in barotrauma if a diver is unable to equalize. A diver can equalize the pressure in their middle ear and sinuses by Valsalva maneuver, or a series of other exercises described elsewhere. A diver positively or neutrally buoyant on the surface may need to use the anchor line to pull themselves down to depth slowly to allow equalization maneuvers to be effective as they descend.

Equalization is more easily performed in a head up rather than a head down position. Once the pressure in the sinuses and middle ear are equal to the pressure in the surrounding water, the diver may continue to descend while equalizing or swim comfortably at that depth. The uncontrolled descent, on the other hand, does not allow time for equalization leading to the collapse of the eustachian tube and sinus ostia trapping low-pressure air[2] (causing a squeeze) in the middle ear or sinuses respectfully. Mask and dry suit squeeze can also occur if pressure is not equalized in those spaces.

When the pressure is not equalized in the middle ear the tympanic membrane can then rupture inward; and if, as is typical, it occurs unilaterally first, severe nystagmus and vertigo ensues which can lead to disorientation and drowning. Similarly, negative sinus pressure can also cause an extreme headache and vomiting with similar results.[3][4]

Uncontrolled Descent Considerations

Uncontrolled descent can also cause damage to the benthic environment and/or physical trauma to the diver by striking objects on the bottom or a shipwreck including other divers. Marine environmental hazards such as sea urchin spines, coral, stonefish, and other hazards may be inadvertently encountered all with consequence. This is a teachable moment for the physician especially for divers that are injured by and have injured the coral reefs. It takes hundreds of years for these delicate reefs to grow but only a moment to damage or destroy them with fins or hands.

Once a diver ventures below 100 feet (33 m), they also must be cognizant of nitrogen narcosis. This condition, also referred to as “rapture of the deep”, was first described in 1826. At that time, the cause of this malady was unknown. It wasn’t until definitive experiments with a pressure chamber in 1935 that nitrogen metabolism was identified as the causative agent. [5]. Symptoms include euphoria, time disorientation, giddiness, decreased reaction time, and a false sense of security. A diver can continue to descend unaware while consuming their limited air supply.

Maintaining neutral or slightly positive buoyancy at depth keeps the diver off the reef, wreck, or cave bottom reducing damage to both the environment and the individual. It keeps them streamline while maintaining a fixed depth.

Common Buoyancy Mistakes on Ascent

Common mistakes new divers or experienced unpracticed divers make during their preparation to ascend include not releasing air they added to their BCD at depth and holding their breath on the way up. As the air expands due to reduced pressure, ascent can become uncontrolled due to lift in the BCD and lungs, allowing pulmonary hyperinflation to develop.

As lung hyperinflation increases, the diver may experience a fullness in the chest leading to pulmonary barotrauma. Small alveoli capillaries can burst, forcing gas into the bloodstream. In the small gas exchange vessels, this can cause arterial blockages and small pulmonary infarcts. Once the air enters the venous system and larger vessels, these bubbles can coalesce leading to pulmonary air embolism. An arterial air embolism can migrate into the central circulation and the brain, causing a cerebrovascular infarct. Slow and constant exhalation can avoid this cascade on the ascent.[6]

Many of the problems that take place on descent are also hazards on the ascent but can be worse. In the sinuses and middle ear, high pressures can cause the Eustachian tubes and sinus ostia to collapse. As the pressure increases, the diver suffers a reverse squeeze with a severe headache and ear pain. The pressure can exceed the tissue of the ostia and Eustachian tubes to resist leading to epistaxis, tympanic membrane rupture with resultant vertigo and hearing loss, and ultimately stenosis and scarring of both the tubes and the ostia.

Treatment of Barotrauma and Decompression Sickness

The diver can accomplish treatment of squeeze and reverse squeeze during the dive. They may either ascend or descend in small increments to relieve the pressure on the ostia and tubes respectfully. Once the pain and excess pressure are relieved attempts to equalize using Val Salva or other maneuvers may be re-attempted, usually successfully, then descent or ascent may be resumed with more frequent efforts to equalize along the way.

Divers with colds, congestion, or allergy symptoms are cautioned against diving as mucus, swelling of the tubes and ostia, and fluids can make equalization difficult and sometimes impossible. A reverse squeeze occurs more often in these divers. When ascending and attempts to equalize fail, an additional maneuver may be attempted to clear a reverse squeeze. By forcefully blowing out through the nose, the diver can generate a negative pressure in the nasopharynx that can open the Eustachian tubes and ostia on the opposite side of the squeeze equalizing pressure.

Finally, rapid and/or uncontrolled ascent can lead to decompression sickness. Rapid expansion and destabilization of nitrogen bubbles in the blood following nitrogen saturation at depth is the primary cause. Treatment may include in-water recompression with slower ascent, transport to a hyperbaric chamber for therapy, the use of first aid 100% oxygen to help clear the nitrogen, or all of the above. These are discussed in detail elsewhere. [7]

Safe Ascent and Emergency Ascents

A note on the safe ascent; current recommendations are that a diver should ascend no faster than 30 feet or 9 meters per minute with a minimum safety stop at 15 feet or 5 meters for 3 minutes. Additional safety stops at deeper depths are recommended based on deeper dive and duration profiles. Beside normal ascent, there are three other emergency ascent types. These are mostly precipitated by low or out of air situations.

The three emergency ascent types from safest to least safe are as follows:

- Alternate Air Source Ascent: using a dive buddy’s octopus regulator or other independent air supply to breath as they ascend at no greater than 30 feet or nine meters a minute;

- Emergency Swim Ascent: alone (or unable to contact a buddy), the diver keeps regulator in mouth, attempting inhalation on ascent (tank air expands), while otherwise slowly exhaling, dumping all BCD air, and swimming upward, stopping by expanding arms and legs to slow rate if necessary;

- Buoyancy Emergency Ascent: alone, the diver ditches their weight belt or integrated weights and rockets to the surface using the residual air in the BCD for added lift, hopefully remembering to exhale on the scent. Buoyancy Emergency ascent should be avoided when possible.

Clinical Conclusions

The Diver Alert Network (DAN) collects data on diving accidents. To this day, in most drownings, the diver has air in their tank and their weight belt on. The majority of diving fatalities are due to cardiac events during the dive or on the surface, usually due to ignoring pre-existing conditions. However, poor buoyancy control and rapid ascent were the number two and three risk factors contributing to diver fatalities.

Diving buoyancy is therefore not trivial. While good buoyancy control makes scuba diving a more pleasant experience, it is also critical to safety and survival while underwater. In out of air emergencies, the over-weighted diver died in a ratio of six to one compared to their buddy. Therefore, buoyancy is more than good physics; it is about a diver’s total situational control over mind, body, equipment, and environment. It includes a diver’s ability to control their panic. They recognize nitrogen narcosis at depth and become extra vigilant of their gauges, ascending to clear their sensorium. They are aware of their remaining air, and ascend slowly with good control, so they have the surplus air on the surface. Finally, in an emergency, they stop and assess, make a plan for correction, and execute it, rather than sacrificing their buoyancy and perhaps their life.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The practice of scuba diving is fundamentally dangerous. It took years to define safety limits. The mechanics and history of buoyancy control provide insight for healthcare staff. Additional challenges become involved when a diver is incapable or unable to control their buoyancy. Understanding the conditions under which a diver is injured helps predict diagnosis and treatment strategies for both physicians and staff. Determining if barotrauma occurred during ascent or descent is critical for healthcare personnel to know when anticipating patient needs.

Treatment strategies described herein are primarily first aid for the diver and boat operators. In remote location facilities with limited resources, treatment suggestions in this article also apply. Obtaining a specialist consultation from Diver Alert Network which is available 24/7 is recommended. More advanced treatment with Hyperbaric therapy is advised but discussed elsewhere.

(Level: IV) Historical cohort or case-control studies; and V-Case series, studies with no controls, and expert opinion.