Introduction

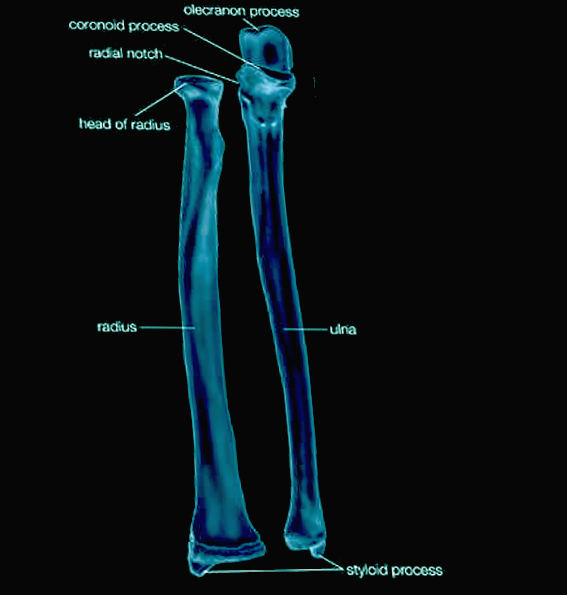

The radius is one of two long bones that make up the human antebrachium, the other bone being the ulna. The radius has three borders, three surfaces, and has a prismoid shape in which the base is broader than the anterior border. The radius articulates proximally at the elbow with the capitulum of the humerus and the radial notch of the ulna. It articulates at its distal end with the ulna at the ulnar notch and with the articular surfaces of the scaphoid and lunate carpal bones.

The most proximal segment of the radius is the radial head. The head is cylindrical and contains the articular disc which articulates with the humeral capitulum and radial notch of the ulna. Distal to the radial head is the neck of the radius and radial tuberosity - an oval prominence that is the site of attachment of the biceps brachii muscle. Distal to the radial tuberosity is the shaft of the radius where multiple muscles attach, including the pronator teres, pronator quadratus, supinator, and extrinsic hand muscles.[1]

Fractures of the distal radius account for some of the most common low-energy fractures seen in ambulatory orthopedics accounting for between 8% and 15% of all bone-related injuries in adults.[2] It is second only to the hip as the most commonly fractured bone in the elderly.[3] Additionally, the subluxation of the annular ligament which stabilizes the proximal radius is an injury commonly seen by pediatricians.

Structure and Function

Function:

The radius permits the forearm and hand to pronate and supinate, flex and extend at the elbow, and adduct, abduct, extend, flex, and circumduct the wrist. Pronation and supination occur through complex articulation with the cylindrical shaped radial head, which is stabilized to the ulnar notch by the annular ligament. This arrangement allows the radial head to rotate proximally, causing anteromedial movement of the distal radius. The distal radius crosses over the distal ulna and inverts to allow the wrist and hand to pronate. A reversal of this movement allows for supination.

In addition to pronation and supination, three articulations allow for extension and flexion at the elbow joint. The elbow joint is a pivot joint (radiocapitellar articulation), a hinge joint (humeroulnar articulation), and a second pivot joint (proximal radioulnar joint). The radius also articulates with the capitulum of the humerus. The olecranon of the ulna articulates with the trochlea of the humerus allowing for the antebrachium to flex and extend with the brachium. While the proximal radioulnar joint's primary function is to enable pronation and supination, the annular ligament maintains proximity between the two bones as the biceps and brachialis contract, causing flexion and allowing the two bones to move as one unit.

Distally, the ulnar notch of the radius and the ulnar head articulate at another pivot joint allowing for supination and pronation. The radius articulates with the wrist via the scaphoid and lunate bones. This articulation is a condyloid or "ellipsoidal" joint which allows the wrist to move in two planes. The radiocarpal joint allows the wrist to adduct, abduct, flex, extend, and circumduct.[4]

Joints and Ligaments:

The lateral ligaments of the elbow are collectively named the lateral collateral ligament complex, which is composed of four ligaments that are difficult to separate. First, the lateral collateral ligament (a.k.a. "radial collateral ligament") attaches from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus to the annular ligament. The lateral collateral ligament joins the radius to the humerus and protects the antebrachium against varus stress. The annular ligament attaches from anterior to the posterior radial notch of the ulna encircling the radial head allowing pronation and supination. The lateral ulnar collateral ligament attaches from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus to the ulnar supinator crest. The lateral ulnar collateral ligament helps protect the antebrachium against valgus stress. Finally, the accessory lateral collateral ligament attaches from the supinator crest to the inferior margin of the annular ligament, providing further stability to the joint.[5]

Between the medial border of the radius and the lateral border of the ulna resides the interosseous membrane which divides the anterior and posterior compartments of the antebrachium. The interosseus membrane serves as an attachment site for muscle while allowing for force distribution across the forearm. When the forearm supinates, the interosseous membrane fibers become taught, stabilizing distal and proximal joints.[6] Like the lateral collateral ligament complex, the composition of the interosseous membrane is of multiple ligaments that are difficult to separate. The five ligaments of the interosseous membrane are the proximal oblique cord, accessory band, central band, dorsal oblique accessory cord, and the distal oblique bundle.[7]

The distal radioulnar articulation is composed of the palmar radioulnar ligament (volar radioulnar ligament) that attaches the anterior radius to the anterior ulna, the dorsal radioulnar ligament (posterior radioulnar ligament) which attaches the posterior radius to the posterior ulna, and the articular disc which lies between the distal ulna and radius. These structures allow for load distribution and allow the second pivot during pronation and supination of the forearm.

The distal radius is attached to the lunate bone via two ligaments, the long and short radiolunate ligaments. These ligaments prevent hyperextension of the lunate bone during wrist extension. The distal radius is attached to the scaphoid via the radial collateral ligament of the wrist, and the radioscaphocapitate ligament attaches the volar aspect of the radius to the scaphoid and capitate carpal bones. Lastly, the dorsal radiotriquetral ligament is a wide ligament, which connects the dorsal radius to the dorsal scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum.[8][9]

Borders and Surfaces:

The radius has three borders (volar, dorsal, and internal) and three surfaces (volar, dorsal, and lateral). The volar border separates the lateral and volar surfaces, the dorsal border separates the lateral and posterior surfaces, and the internal (interosseous border) separates the volar and dorsal surfaces.

The volar surface (anterior surface) provides the site of origin to the flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum superficialis muscles, and site of insertion to the pronator quadratus, supinator, and biceps brachii muscles. It also provides the surface for the anterior radiocarpal ligament attachment. The dorsal surface provides the origin site to the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis muscles as well as the insertion for the rest of the supinator muscle. The lateral surface provides the insertion sites for the brachioradialis and pronator teres muscles. These are generalizations of where each muscle attaches, and in addition to anatomical variation, many of the muscles attach to more than one radial surface.[10][11]

Embryology

The development of the radius occurs through endochondral ossification and begins with lateral plate mesoderm - the origin of all long bones. Endochondral ossification is the replacement of hyaline cartilage with bone. Mesoderm-derived mesenchymal cells become chondrocytes, which proliferate rapidly and form a bone template.

Chondrocytes near the center of the model begin laying down collagen and fibronectin to the matrix which allows for calcification. Around week six of gestation, the calcification prevents nutrients from reaching the chondrocytes. The chondrocytes eventually undergo apoptosis. Blood vessels proliferate through the spaces vacated by the chondrocytes and eventually form the medullary cavity. Around the 12th week of gestation, osteoblasts create a thick area of compact bone in the diaphysis called the periosteal collar which becomes the site of primary ossification. Epiphyseal plates (growth plates) at either end of the bone contain proliferating chondrocytes, that continue to elongate the bone, until puberty. During puberty, sex hormones cause secondary ossification centers to form, and the epiphyseal plates ossify in a congruent fashion as the diaphysis.[12][13][14]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the proximal radius is provided primarily by the radial and radial recurrent arteries. The radial recurrent artery travels proximally to anastomose with the radial collateral artery. Blood supply to the middle and distal radius is through the radial, posterior interosseous, and anterior interosseous arteries.[15]

Lymph from the radius drains via the deep lymphatic vessels which follow the deep veins such as the brachial, ulnar, and radial veins. These vessels drain into the humeral axillary lymph nodes.[16]

Nerves

The nerves of the brachial plexus provide motor and sensory innervation to the antebrachium.

The radial nerve provides sensory innervation for the posterior forearm and motor innervation to the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor carpi radialis longus, supinator, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, abductor pollicis brevis, extensor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor indicis, extensor digitorum, and extensor digiti minimi muscles.

The medial and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves provide sensory innervation to the anteromedial and anterolateral forearm respectfully.

The musculocutaneous nerve is the source of motor innervation to the biceps brachii.

The median nerve provides motor innervation to the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus, and the lateral half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscles.

The ulnar nerve supplies motor innervation to the flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus muscles.[17]

Muscles

The muscles of the forearm divide into two compartments - posterior and anterior. The posterior compartment is composed primarily of muscles that allow for wrist extension, finger extension, and forearm supination. The anterior compartment contains mostly the muscles involved in wrist flexion, finger flexion, and forearm pronation.

The anterior compartment subdivides into the superficial, intermediate, and deep layers. The muscles of the superficial layer are the flexor carpi ulnaris, palmaris longus, flexor carpi radialis, and pronator teres. The intermediate layer contains a single muscle, the flexor digitorum superficialis. The deep anterior layer is composed of the flexor digitorum profundus, the flexor pollicis longus, and the pronator quadratus.

The posterior compartment of the forearm subdivides into superficial and deep layers. The muscles of the superficial layer are the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris, and anconeus muscles. The muscles of the posterior layer are supinator, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor pollicis longus, and extensor indicis muscles.

Physiologic Variants

In addition to documented cases of short, hypoplastic, or absent radial bones, the proximal radio-ulnar synostosis is a malformation caused by the bony fusion of the proximal radius and ulna. The proximal third of both bones are the most common sites of fusion. The malformation correlates with an increased incidence of posterior dislocation of the radial head. Proximal radio-ulnar synostosis has associations with Poland syndrome, Cenani-Lenz syndactyly, and Cornelia de Lange syndrome.[18][19]

Surgical Considerations

Fractures of the radial head and neck comprise 1% to 5% of pediatric elbow fractures. The most common fractures involve the epiphysis and the metaphysis.[20]

Distal radial fractures are much more common than radial head and neck fractures. Most commonly, distal radial fractures occur when a patient falls on an outstretched hand resulting in the dorsal displacement of the fragment. These fractures often heal without required surgical intervention; however, more complex fractures require an orthopedic consult. A complex fracture of the distal radius occurs when there is a presence of ligamentous instability, carpal fracture, or articular involvement, or volar displacement. These fractures often require operative treatment.[21]

Clinical Significance

Subluxation of the annular ligament (a.k.a. nursemaid's elbow or radial head subluxation) is one of the most common pediatric injuries seen by ambulatory orthopedics. It occurs with the application of sudden longitudinal traction to the hand or forearm of a child younger than 5 years old. With sudden traction, the radial head slips from under the ligament, and the ligament becomes trapped between the capitulum and the radial head. The child often presents with a refusal to use the affected limb while carrying his/her elbow in slight flexion with the forearm pronated.[22][23]

A Smith fracture occurs at the distal radius, often from a direct blow to the dorsal wrist or forearm. The injury can also occur with a fall on a flexed wrist. The fracture is displaced ventrally, which differs from a Colles fracture where the fragment is displaced dorsally. Unlike nursemaid's elbow, which is seen almost exclusively in pediatric patients, distal radius fractures are seen commonly in those younger than 18 or older than 50 years old.[24]

Colles fracture also involves an injury to the distal radius. The avulsion fracture occurs most commonly when a person falls on an outstretched hand while the forearm is pronated. There is dorsal displacement of the bone fragment and the subluxation of the annular ligament. The description of the injury is as causing a "dinner fork" or "bayonet" deformity clinically.[25]

Barton fracture is very similar to the Colles fracture. It most commonly occurs when a person falls on an outstretched hand with the arm pronated. The impact causes a shearing fracture of the distal radius. The fracture moves dorsally but does not disrupt the radiocarpal ligaments. The articular surface of the distal radius remains in contact with the scaphoid. This difference is what distinguishes the Barton fracture from the Colle's fracture.[26]

Holt-Oram syndrome (HOS) is an autosomal dominant mutation in the TBX5 gene that results in upper-limb and cardiac defects. Upper-limb malformations include the triphalangeal or absent thumb(s), unequal arm length caused by aplasia or hypoplasia of the radius, or fusion of the carpal and thenar bones. Aplasia or hypoplasia of the radius results in abnormal forearm pronation and supination as well as abnormal wrist adduction and abduction.[27]