Continuing Education Activity

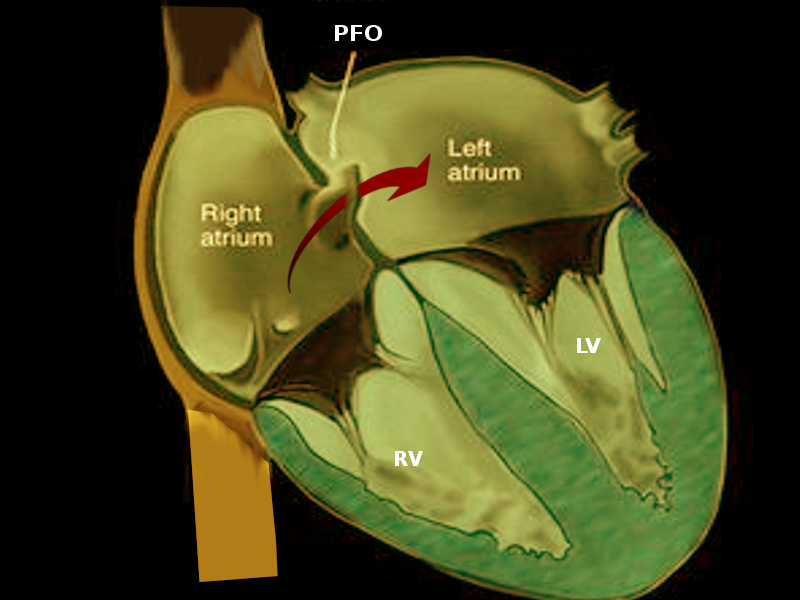

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a common abnormality that describes the presence of a small opening between the top two chambers of the heart. Several large, population-based studies estimate that transcatheter closure of PFO in addition to medical therapy is superior to medical therapy alone in preventing recurrent cryptogenic stroke; it bears mention that PFO closure in these patients has not demonstrated a reduction in the risk of recurrent transient ischemic events (TIA) or all-cause mortality. This activity reviews the role of percutaneous closure of the PFO and its indications and contraindications and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of patients with congenital heart defects.

Objectives:

Identify the indications for percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO).

Describe the technique of percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO).

Recall the contraindications of percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO).

Explain how an interprofessional team approach can manage percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO) and improve patient outcomes.