Introduction

The mylohyoid is one of the muscles essential in performing the functions of swallowing and speaking. It is a flat and triangular muscle that originates from the mandible near the molars hence the prefix “mylo” (Greek for molars) and inserts on the hyoid bone. The mylohyoid mainly functions to elevate the hyoid bone, elevate the oral cavity, and depress the mandible. The source of motor innervation is via the mylohyoid nerve, which is a division of the inferior alveolar nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The blood supply is from the mylohyoid artery, a branch of the inferior alveolar artery which originates from the internal maxillary artery. The mylohyoid muscle forms a contractile hammock to support the oral cavity base.

Structure and Function

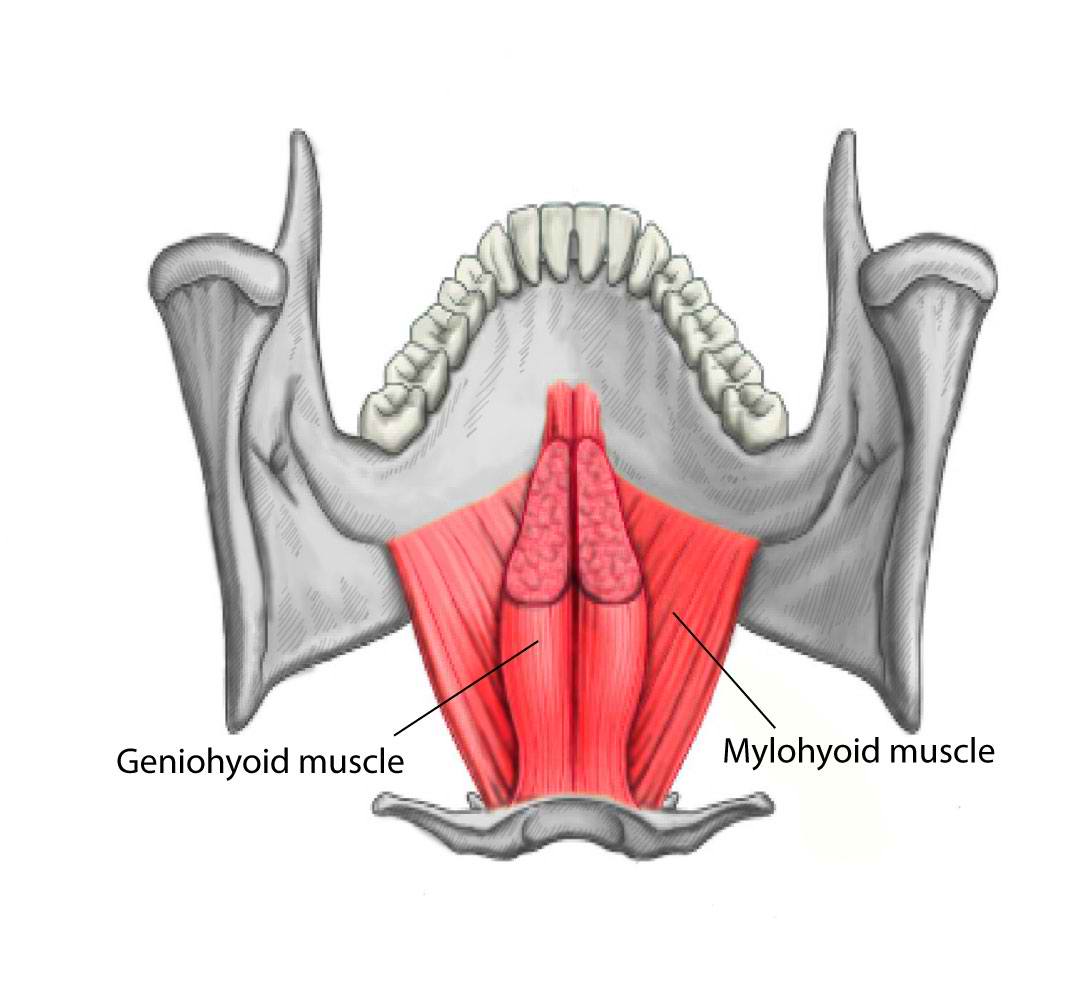

The mylohyoid muscle is composed of two different subunits that come together to form the entire mylohyoid muscle. The mylohyoid muscle originates from the mylohyoid line located within the interior surface of the mandible near the molars of the lower jaw and continues along the entirety of the inner mandibular rim. The mylohyoid muscles on each side of the inner surface of the mandible meet medially at a median tendon called the mylohyoid raphe. The middle and anterior fibers of the mylohyoid muscle form the mylohyoid raphe which extends from the symphysis menti to the body of the hyoid bone. The posterior fibers of the mylohyoid muscle pass medial and downward to insert on the body of the hyoid bone. The oral diaphragm is a muscular floor of the oral cavity that bridges between the two rami of the mandible and forms from the mylohyoid muscle. The mylohyoid muscle is superior and deep to the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and deep to the stylohyoid muscle. The mylohyoid muscle separates the submandibular region and the sublingual region. Finally, the deep mylohyoid muscle forms the floor of the submental triangle, which is defined by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle laterally, hyoid bone inferiorly, and the platysma muscle superficially.[1][2]

The mylohyoid muscle maintains a critical participant in day to day activities, including mastication and swallowing of food and production of speech in conversations. A key mechanism of action of the mylohyoid muscle is it works directly and indirectly with the infrahyoid muscle to guide the position of the hyoid bone. When the mylohyoid muscle contracts during swallowing, it functions to elevate the base of the tongue and the hyoid bone anterosuperior with the mandible fixed. Per these actions, the mylohyoid muscle also depresses the mandible and elevates the oral cavity if the hyoid bone is in a fixed position from the action of its depressors. The mylohyoid muscle acts as a support structure to reinforce the base of the oral cavity by forming the oral diaphragm.[1]

Embryology

The mylohyoid muscle derives from the first pharyngeal arch and is a member of the suprahyoid muscles. The first pharyngeal arch forms during the fourth week of gestation and directs the development of the midface and lower face. The arch is composed of the maxillary and mandibular processes. The mandibular process gives rise to the mandible, which is the origin of the mylohyoid muscle. A mesodermal component of the first pharyngeal arch is what serves as the derivative of the mylohyoid muscle along with the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, tensor veli palatine muscle, tensor tympani muscle, and muscles of mastication.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The mylohyoid muscle mainly obtains its blood supply from the mylohyoid artery, a branch of the inferior alveolar artery, which is a branch of the first portion of the maxillary artery. The maxillary artery supplies components within the face and is a tributary of the external carotid artery formed deep to the mandible neck. A common course of the maxillary artery is from its origin point deep to the mandible neck extending between the mandible ramus and ligament of the sphenomandibular to the lateral pterygoid muscle and finally to the fossa of the pterygopalatine. Hence, one frequently sees references to the maxillary artery as having three divisions, which include the pterygoid, pterygopalatine, and mandibular segments. The mandibular portion (bony portion) has five major branches including the middle meningeal artery, accessory meningeal artery, deep auricular artery, anterior tympanic artery, and the inferior alveolar artery. The inferior alveolar artery yields the mylohyoid branch just before entering the mandibular foramen. The mylohyoid branch runs in the mylohyoid groove where it functions as the primary vascular source for the mylohyoid muscle.[4]

Nerves

The mylohyoid nerve innervates the mylohyoid muscle. The inferior alveolar nerve is a branch from the posterior division of the mandibular division (V3) of CN V (trigeminal nerve). The mylohyoid nerve is a branch of the inferior alveolar nerve which contains both sensory and motor components.[5]

The mylohyoid nerve forms before the inferior alveolar nerve enters the mandibular foramen. The mylohyoid nerve travels in the mylohyoid groove located within the medial portion of the ramus towards the medial pterygoid muscle. Within this portion of the mandible, the mylohyoid nerve travels anteroinferior and pierces the sphenomandibular ligament. It continues its course until it meets the inferolateral segment of the mylohyoid muscle where it yields motor branches to innervate both the mylohyoid muscle inferiorly and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle superiorly. The mylohyoid nerve also carries afferent sensory innervation to the mandibular molars and the skin inferior of the chin and lower lip. Additionally, when the mylohyoid nerve approaches the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle, it is associated with the medial aspect of the submandibular gland.[6][7]

Muscles

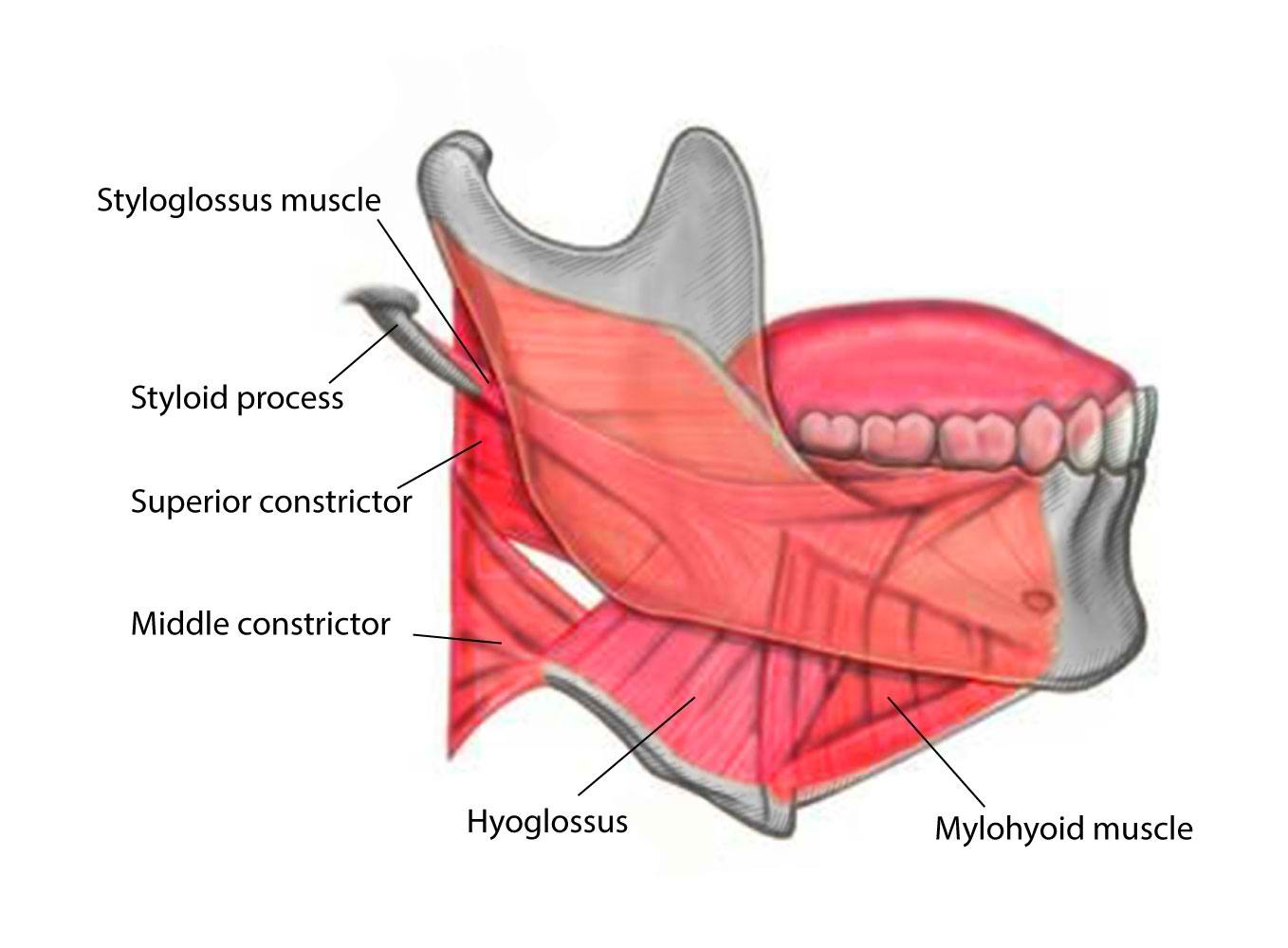

The classification of the suprahyoid muscles includes four muscles that run from the mandible to the hyoid bone. These four muscles come together to form the floor of the mouth. The paired mylohyoid muscle is one of these muscles, along with the geniohyoid muscle, digastric muscle, and stylohyoid muscle. These muscles play a vital role in mastication and are frequently referred to as accessory muscles of mastication by influencing the motion of the hyoid bone.

The mylohyoid muscle originates from the mylohyoid line of the mandible and inserts on the body of the hyoid bone. The mylohyoid muscle functions to depress the mandible and elevate both the oral cavity and the hyoid bone. The stylohyoid muscle has its origin from the styloid process of the temporal bone and inserts on the lateral surface of the body of the hyoid bone at its junction with the greater cornu. The contraction of the stylohyoid muscle elevates and retracts the hyoid bone, especially during swallowing. Two bellies comprise the digastric muscle; there are the anterior belly and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The posterior belly of the digastric muscle originates from the mastoid notch, which is a deep groove between the mastoid process and the styloid process of the temporal bone and inserts on the body of the hyoid bone. The anterior belly of the digastric muscle originates from the digastric fossa on the posterior surface of the mandible and inserts on the body of the hyoid bone. The contracture of the digastric muscles causes elevation of the hyoid bone, or depression of the mandible if the hyoid bone is being locked in place by the strap muscles. The geniohyoid muscle originates from the mental spine of the mandible and inserts on the body of the hyoid bone. Contraction of the geniohyoid muscle cause elevation and forward protrusion of the hyoid bone along with depression of the mandible.[8]

During the first action of swallowing when a bolus of food gets driven from the oropharynx into the pharynx, the hyoid bone and the tongue are carried upward and forward by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, mylohyoid muscle, and the geniohyoid muscle. In the second act of swallowing, when the bolus is passing through the pharynx, the elevation of the hyoid bone is organized by the combined action of all these suprahyoid muscles. After the bolus has passed through the pharynx, the hyoid bone is driven superior and posterior by the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and the stylohyoid muscle to prevent the regurgitation of food back into the oral cavity.[8]

Physiologic Variants

The mylohyoid muscle may have an absent median raphe. Therefore, the muscle would be continuous rather than composed of two segments. In some cases, the mylohyoid muscle may be replaced by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle or in unison with this muscle as they both originate from the first pharyngeal arch during development.[9]

Surgical Considerations

In the case of the surgical excision of the submandibular gland, the branch of the mylohyoid that provides sensory innervation to the area beneath the chin may be at risk for an injury which may cause an alteration in sensation to this area.

Clinical Significance

Plunging ranula:

A ranula is a mucous cyst seen within the base of the mouth. The etiology of a ranula is often due to acquired traumatic incompetence in the structure of a surrounding salivary gland duct located within the submandibular or sublingual spaces leading to the accumulation of mucus or saliva from gland rupture secondary to hypertension. This mucus is often composed of a higher concentration of proteolytic enzymes such as matrix metalloproteins and type IV collagenase than normal saliva contributing to the locally invasive nature of a ranula.

A simple ranula is located only within the sublingual space. However, herniation of the mucous via the mylohyoid muscle boutonniere (normal discontinuity within the mylohyoid muscle that allows for communication between the sublingual and submandibular spaces) generates a specific type of ranula called a plunging ranula that involves the submandibular space. A plunging ranula often presents as a painless swelling of the lateral neck that occurs during the third decade of life, unlike a ranula which is often a bluish mass at the base of the oral cavity. Complications of a plunging ranula include disruption in the patient’s ability to speak or chew, which can eventually progress to dyspnea secondary to obstruction when the cyst involves the parapharyngeal space. Diagnostic confirmation is by the supporting clinical findings along with imaging to evaluate the underlying lesion involvement. MRI of the mass would reveal low signal with T1 and high signal with T2. While ultrasound would reveal a thin-walled hypoechoic cystic lesion that may have increased attenuation if an infection is present. Treatment includes surgical excision of the cyst and associated sublingual gland and rare cases requiring submandibular gland removal or Picibanil directed sclerotherapy with a high rate of recurrence.[10][11]

Ludwig's angina:

Ludwig’s angina is necrotizing cellulitis of the base of the oral cavity that may progress quickly and involve the submaxillary and submandibular spaces. Often seen secondary to periodontal abscesses.

The mylohyoid muscle separates the sublingual and submandibular spaces, but a finite line of communication remains between these two spaces posterior to the mylohyoid muscle. Infections that originate in the teeth can spread from one space to the other via this communication or breach the mylohyoid muscle itself.[12]

Patient present with submandibular and sublingual swelling that is exquisitely tender along with associated fevers and chills. Complications include subsequent deep neck infections, thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, subphrenic abscess, carotid artery rupture, or mandibular osteomyelitis. In the worst-case scenario, this infectious entity progressively worsening tongue swelling can cause airway obstruction, which can lead to death by asphyxia.[13]