Introduction

The dorsal interosseous muscles are a group of paired intrinsic muscles of the hand located between the metacarpals. They consist of four dorsal muscles that abduct the fingers. The dorsal interossei additionally assist in flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joints and extension of the interphalangeal joints. All interossei muscles receive innervation by the deep ulnar branch of the ulnar nerve. As such, any injury to the ulnar nerve may have debilitating implications on specific intrinsic hand muscle functions, including finger abduction and adduction, which are primarily controlled by the interossei muscles.

These small muscles, despite their limited range of motion and together with the interosseous palmar muscles, play key roles in the function of the hand: grip and pinch.

Structure and Function

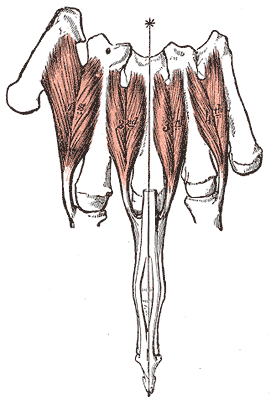

Of all the intrinsic muscles of the hand, the dorsal interossei are the most dorsally located. The bipennate dorsal interossei are the major abductors of the second, third, and fourth digits at the metacarpophalangeal joints. Moreover, they also contribute to flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joints in addition to the extension of the PIP and DIP joints.

The first dorsal interosseous muscle has its origin on the adjacent surfaces of the first and second metacarpal bones and inserts into the lateral base of the second phalanx and extensor hood of the second digit.

The second dorsal interosseous muscle originates on the medial aspect of the second metacarpal and the lateral aspect of the third metacarpal bone. It inserts into the lateral base of the third phalanx as well as the respective extensor hood.

The third dorsal interosseous muscle originates at the medial portion of the third metacarpal and the lateral portion of the fourth metacarpal. Its insertion is at the medial base of the third phalanx in addition to the extensor hood of the third digit.

The fourth dorsal interosseous muscle originates at both the lateral aspect of the fourth metacarpal and medial side of the fifth metacarpal. This muscle inserts into the lateral base of the fourth phalanx and the extensor hood of the fourth digit.

Embryology

At the end of the fourth week of embryonic development, four limb buds arise from somites and mesenchyme of the lateral plate mesoderm that is covered by a layer of ectoderm.[1][2] Development of the upper extremities is propagated by a plethora of protein factors, with fibroblast growth factors (FGF) and Sonic hedgehog (Shh) playing vital roles. The gene expression and subsequent interactions of these various proteins contribute to the development of three spatial limb axes: proximodistal, anteroposterior, and dorsoventral.[1][2]

Development of the hand begins with flattening of the distal upper extremity buds around days 34-38 of embryonic development. Somites form the limb musculature while mesenchyme of the lateral plate mesoderm forms bone and cartilage. Somitic mesoderm of the hand divides into superficial and deep layers. Both palmar and dorsal interossei muscles develop from the deep layer of this mesoderm. By the twelfth week of development, tendons are fully developed and functional.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The first dorsal interosseous muscle receives vascular supply by the first dorsal metacarpal artery, which arises directly from the radial artery. The second, third, and fourth dorsal interossei receive blood supply from the second, third, and fourth dorsal metacarpal arteries, arising from the dorsal carpal arch. All dorsal metacarpal arteries bifurcate into their respective dorsal digital arteries and anastomose with the common palmar digital arteries.

The drainage of venous blood from the fingers of the hand is the digital palm veins, the dorsal digital veins, and the intercapitular veins, constituting a complex vascular network. These venous vessels carry blood in the superficial palmar venous arc and in the dorsal venous arc, which arches communicate with ulnar, cephalic and basilic veins.

Lymphatic drainage of the upper limbs divides into superficial and deep lymphatic drainage. Lymphatic plexuses of the skin of the palm and dorsum of the hand ascend with the cephalic and basilic veins towards the axillary and cubital lymph nodes, respectively. Deep lymphatic vessels follow the primary deep veins and eventually terminate in the humeral lymph nodes.

Nerves

Both the palmar and dorsal interossei get their nerve supply by the deep branch of the ulnar nerve. The deep branch of the ulnar nerve derives from nerve roots of C8 and T1 with T1 being the major innervating segment.

Physiologic Variants

Classically, students are taught that all dorsal interossei have two heads, termed bipennate. One retrospective study found that approximately 25 percent of dorsal interossei are unipennate.[3] This study also concludes that traditional teachings have oversimplified the attachment sites of both palmar and dorsal interossei, which possess a high degree of variability. These distal attachment sites include bony attachments, the volar plate, and any portion of the extensor hood.[3]

Surgical Considerations

Treatment for metacarpal fractures is usually with hand surgery, with metacarpal shortening ranging from 2mm to 10mm. Researchers have found that in metacarpal shortening of 2 mm, there is an approximate 8 percent in strength reduction of the respective interossei. Moreover, a 10mm shortening can reduce the respective interossei strength of roughly 55 percent.[4]

Compartment syndromes of the interossei are uncommon and are difficult to diagnose due to their atypical presentations.[5]They typically occur in patients who have suffered crush injuries, burns, or severe ischemia. One case report found a first dorsal interosseous compartment syndrome in a teacher, likely through overuse injury due to writing. This injury went undiagnosed for eight years and was relieved through simple tendon sheath decompression.[5] Styf et al. additionally described their observations of fifteen patients with first dorsal interosseous compartment syndrome, all of which were relieved with fasciotomy.[6]

Another case study described two children who experienced suction injuries when their hands got caught in a swimming-pool intake pipe filtration system. This system created a powerful negative pressure, causing acute interossei compartment syndrome that required emergent surgical decompression.[7] As noted in other studies describing the procedure, two incisions were made, one between the index and middle fingers and the other between the middle and ring fingers.[7][8]Dissection along the sides of the metacarpals released the dorsal interossei, with further dissection along the index metacarpal released the first palmar interossei and the adductor compartment. Subsequent deep dissection along the radial and ulnar aspects of the ring metacarpal released the remaining palmar interossei.[7][8]

Clinical Significance

The dorsal interossei receive innervation from the deep palmar branch of the ulnar nerve. As such, injury to the ulnar nerve can manifest as weakness or even atrophy of the interossei muscles and is typically caused by nerve root impingement, brachial plexus compression, or nerve entrapment at the elbow, forearm, or wrist. Ulnar nerve entrapment is the second most prevalent compression with which neuropathy patients present.[9] Depending on which nerve fibers are compromised, patients may have weakness in abduction of the fingers. The lumbricals are the major contributors to flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joints, as well as extension at the DIP and PIP joints; however, the interossei also play a minor role in these movements. A late manifestation of ulnar nerve injury, the ulnar claw hand deformity is caused by weakness of the third and fourth lumbricals, in addition to the interossei, which manifests as weakness in extension of the fourth and fifth metacarpophalangeal joints and flexion of the fourth and fifth PIP and DIP joints.[9]

Several clinical examinations are used to assess the integrity of ulnar nerve function. Clinicians can evaluate dorsal interossei by instructing a patient to abduct their second through fifth digits against the clinician’s resistance. A weakness of this action would indicate an ulnar nerve injury.[9]