Continuing Education Activity

In order to improve health outcomes for patients, practitioners should recognize that yersinia enterocolitica has an acute diarrheal form of infection as well as pseudoappendicitis which mimics appendicitis (both requiring different treatment strategies). This activity reviews the evaluation and management of yersinia enterocolitica and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the recognition and management of this condition.

Objectives:

- Discuss the recommended management of yersinia enterocolitica.

- Outline the typical presentation (acute yersiniosis and pseudoappendicitis) for a patient with yersinia enterocolitica.

- Review the pathophysiology of yersinia enterocolitica.

- Explain the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with yersinia enterocolitica.

Introduction

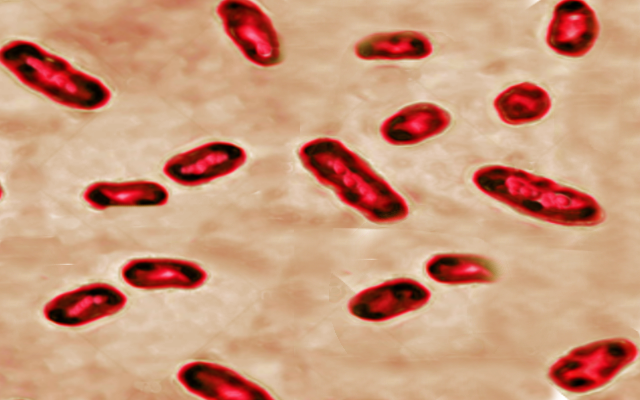

Yersinia enterocolitica is a gram-negative bacillus shaped bacterium that causes a zoonotic disease called yersiniosis. The infection is manifested as acute diarrhea, mesenteric adenitis, terminal ileitis, and pseudoappendicitis. In rare cases, it can even cause sepsis.[1][2][3]

In some countries, yersinia infections have overtaken shigella and salmonella species as the most common cause of bacterial gastroenteritis. While most cases are sporadic, large outbreaks are not uncommon. Humans acquire yersinia after consumption of contaminated food as well as a blood transfusion. The one key feature of yersinia is that the individual will continue to shed the organism in feces for nearly 3 months after symptoms have subsided- thus detection of yersinia in stools is critical.

Etiology

The genus Yersinia includes 11 species, of which 3 are notable for causing human diseases: Yersinia pestis, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Yersinioses are zoonotic infection with the human being the incidental hosts who do no contribute to the life cycle for the pathogen.

Yersinia are classified based on their biochemical features and of the 6 biotypes, subtypes 2,3, and 4 are most common in humans.

Epidemiology

Y. enterocolitica have been isolated from a variety of animals with pigs being the most common source. The pathogen can spread from one pig to another in a herd. The bug can contaminate pork products including neck trimmings, tongue, tonsils and can spread to other meat cuts during slaughter.[4][5]

Yersinia is classified according to their phenotype and serotype. Phenotypically, these bugs are divided into 6 bio groups out of which 5 (1B and 2-5) are regarded as pathogens. Based on serotyping, this pathogen is classified into more than 57 O serogroups. However, only a few of these are pathogenic. The pathogenic serotypes are O:3 (biogroup 4), O:5,27 (biogroup 2 and 3), O:8 (biogroup 1B), and O:9 (biogroup 2). The most common serogroup isolated from humans in European countries is O:3 followed by O:9. In the United States, serogroup O:8 is more prevalent.

Pathophysiology

Infection is transferred predominantly through the fecal-oral route. Pork consumption especially undercooked or raw pork products are responsible for yersiniosis. Outbreaks have also been reported in Norway and New Zealand from untreated drinking water contaminated with this pathogen. There are case reports of infection being transferred from an infected household pet and through transfused blood products.

The pathogen passes into the stomach, traverses the gut wall, and localized in lymphoid tissue and mesenteric lymph nodes. The bacteria has a 70 kilodalton virulent plasmid known as pYV that is present in pathogen species of Yersinia including enterocolitica, pestis, and pseudotuberculosis. The bacteria also produce ureases that metabolized urea and forms ammonia to protect itself from the harsh acidic environment of the stomach. The bacteria also produce Ail (attachment invasion focus) and YadA, that confers resistance to complement-mediated opsonization and prevents phagocytosis. The bacteria also contains Yops (Yersinia outer membrane proteins) that arrests phagocytosis by block secretion of mediators including TNF-alpha and IL-8. Certain strains produce yersiniabactin that is an iron-binding agent that can effectively bind iron in a depleted state. This further allows the bacteria to thrive and grow.

The pathogenesis of reactive arthritis is likely due to an immune response that is primarily to Yersinia antigens that cross-reacts with host antigens. The host may have HLA-B27 positivity making them susceptible to reactive arthritis. The other common post-infectious sequela is erythema nodosum.

Yersinia can invade the epithelial cells and penetrate the mucosa, resulting in colonization of lymphoid tissue (Peyer patches). From here, the organism can spread to other organs.

One unique feature of yersinia is that it cannot chelate iron, which is an essential growth factor. Yersinia utilizes siderophores produced by other organisms to chelate iron. Iron overload is known to increase the severity of Yersinia enterocolitis.

History and Physical

Yersinia infections can present with enterocolitis, pseudoappendicitis, reactive arthritis, sepsis, pharyngitis, myocarditis, mesenteric adenitis or dermatitis. Clinically the infection can manifest in 2 ways:

Acute Yersiniosis

This condition manifests as diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. The duration of diarrhea can range from 12 to 22 days. Yersiniosis is difficult to distinguish from other causes of acute diarrhea given the similar presentation. The localization of pain to the right lower quadrant may be a diagnostic clue for yersiniosis. Bloody diarrhea is more frequently observed in children compared to adults. Sepsis has been described in infants and patients who are immunocompromised or in iron overload state with an overall 50 percent fatality rate.

Following the acute infection, the bacteria may continue to shed in the stool for a median of 40 days (range 17 to 116 days).

Pseudoappendicitis

Acute yersiniosis can mimic appendicitis and present with right lower quadrant abdominal pain, fever, vomiting, elevated white blood count, and diarrhea. Patients taken for surgery demonstrate inflammation of the terminal ileum and mesenteric lymph node with a normal appendix. Pseudoappendicitis is most common in young children resulting in appendectomy in many cases.

Reactive arthritis can also occur after yersinia and tends to affect multiple joints. The larger joints are usually involved and the symptoms may last for 30-120 days. In most cases, the joint symptoms appear 7-14 days after the gastrointestinal symptoms.

Another feature of yersinia is erythema nodosum with lesions appearing 2-14 days after the abdominal pain. The lesions are more common in adult females and usually resolve on their own.

Evaluation

The blood work is usually unremarkable, but in severe cases of diarrhea, one may observe hypernatremia and hypokalemia. A stool culture is the best way to make a diagnosis of Yersinia. Precautions should be in place to avoid infection from stool contact. The gram stain may reveal 'safety'pin' like organisms.

Blood cultures are usually negative. Other studies depend on the organ system involved. Imaging studies (e.g., ultrasound or CT scan) are often required to determine if the patient has appendicitis or pseudoappendicitis. Diagnosis may also be obtained from positive cultures obtained from mesenteric lymph nodes, pharyngeal exudates, peritoneal fluid, or blood.[6][7]

Serologic tests including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and immunoblotting to detect IgG, IgA and IgM are used in Japan and Europe but not very commonly used in the US. Polymerase chain reaction and immunofluorescence assays have been developed but not widely used.

Colonoscopy is not usually done but when performed, it may reveal aphthoid lesions and ulcers in the terminal ileum. In most cases, the right side of the bowel is involved.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of Yersinia is supportive care with hydration and nutritional support. The drugs of choice are the aminoglycosides or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Other effective agents include tetracycline (not in children), quinolones and cephalosporins. Sometimes surgery is required to drain an abdominal abscess, and surgical exploration is warranted if appendicitis cannot be ruled out. It is important to note that in many cases, pseudoappendicitis and appendicitis cannot be differentiated on a clinical exam or even with imaging. Thus, some patients undergo surgery for removal of an appendix. In such scenarios, the appendix is found to be normal, but there is localized mesenteric adenitis, which is confirmed by the pathologist. Antimotility agents should be avoided in patients with diarrhea, as they may worsen the infection. Antibiotics should be used only in selected patients such as the elderly, immunocompromised individuals or patients with diabetes. Children may need admission for dehydration or sepsis. Most patients are anorexic and may require an overnight admission for intravenous (IV) hydration. In some cases, patients are admitted because it is not possible to rule out appendicitis.[8]

Prevention

The preventive measures include handwashing after exposure to an exposed animal, safe food processing, avoiding raw consumption of pork and products, routine water treatment and disinfection, and screening for the pathogen in blood and blood products.

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis depends on a detailed history, detailed physical examination and supportive laboratory and radiological findings. Diseases that can present in a similar include:

- Acute diarrhea (secondary viral, bacterial, protozoal, fungal organisms)

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Diverticulitis

- Appendicitis

- Medication-associated colitis

- Ischemic Colitis

- HIV, influenza, dengue fever, malaria (developing countries)

- Radiation colitis

- Diversion Colitis

- Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

- Cancer of Colon, small bowel

Prognosis

Yersiniosis generally has a favorable outcome. A study from the United States reported only 1.2% (18 deaths out of 1373 patients) diagnosed with Yersiniosis. In another study from Norway, only 2 deaths were reported from 458 patient diagnosed with yersiniosis.

However, yersinia does have other morbidity that includes:

- Pseudoappendicitis

- Erythema nodosum

- Pharyngitis

- Mesenteric adenitis

- Glomerulonephritis

- Myocarditis

- Dermatitis

Conditions that cause hemolysis and release iron increase the risk of systemic infection. In addition, use of deferoxamine also enhances the risk of Yersinia enterocolitis.

Complications

Complications related to Yersiniosis include:

Gastrointestinal

- Bowel perforation

- Peritonitis

- Diffuse ulcerating ileitis and colitis

- Intussusception

- Paralytic ileus

- Cholangitis

- Mesenteric Vein thrombosis

- Toxic Megacolon

- Small bowel Necrosis

Extraintestinal

- Hepatic abscess

- Splenic abscess

- Septicemia

- Renal abscess

- Osteomyelitis

- Lung abscess

- Endocarditis

- Suppurative Lymphadenitis

- Skin infection

- Mycotic aneurysm

- Foreign body infections (catheters/prosthesis)

- Myocarditis

- Glomerulonephritis

- Liver Failure

Consultations

Patients presenting with appendicitis needs evaluation by general surgery for surgical exploration to evaluate the etiology.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be counseled regarding hydration and electrolyte intake if they have uncomplicated diarrhea that can be observed.

Education including proper food processing, handwashing, and avoidance of raw pork products should be done to prevent infection.

Care should be sought immediately if the patient develops severe symptoms/complications including fever, bloody bowel movements, abdominal distension, toxic appearance, decreased urinary output, among others.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Yersiniosis is an acute diarrheal illness that is caused by 3 species of Yersinia: enterocolitis, pestis, and pseudotuberculosis.

- Diagnosis is predominantly based on positive stool culture.

- Initial treatment for uncomplicated diarrhea involves hydration, nutrition and electrolyte replacement.

- Emergency care should be sought if the patient develops worsening symptoms or complications.

- Handwashing, hygiene, and avoidance of raw pork products is the best way to prevent these infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Yersinia enterocolitica is a gram-negative bacillus shaped bacterium that causes a zoonotic disease called yersiniosis. The infection is manifested as acute diarrhea, mesenteric adenitis, terminal ileitis, and pseudoappendicitis. In rare cases, it can even cause sepsis. Over the past few decades, yersinia infections have become very common with epidemics reported in many parts of the globe.

Since the majority of patients with yersinia infection present to the emergency department, nurses and emergency dept physicians should be aware of the presentation, diagnosis, and management. While most patients do improve with hydration, some may require antibiotics.

The public health nurse should be involved when there is an epidemic because education of the public is vital. The key to prevention is to educate the patients on the importance of handwashing and maintenance of personal hygiene. Travelers to endemic areas should be told to wash all fruit and vegetables and avoid consuming unpasteurized milk. For those patients who are hospitalized, nurses should ensure that enteric precautions are in place.

Close communication between members of the team is essential in order to improve outcomes.