Introduction

The popliteal vein is located posterior to the knee in the popliteal region that is a major route for venous return from the lower leg. The vein forms from the combination of the anterior and posterior tibial vein at the border of the popliteal artery. The vein is found in the popliteal fossa on the posterior aspect of the knee. The vein crosses from the medial to the lateral side of the popliteal artery in the fossa. It is considered a deep vein of the leg. However, it has both deep and superficial tributaries contributing to its blood flow. The popliteal vein is renamed to the femoral vein after it passes through the adductor hiatus in the thigh.[1]

Structure and Function

The popliteal vein is responsible for much of the drainage from the lower leg. The vein drains into the femoral veins which flows into the inferior vena cava to return to the right atrium of the heart. The posterior tibial vein, peroneal vein, and the anterior tibial vein are all deep veins of the lower leg that converge to form the popliteal vein at the level of the popliteus muscle. The small saphenous vein is a superficial vessel that drains the posterior, lower leg, and empties into the popliteal vein. [1]

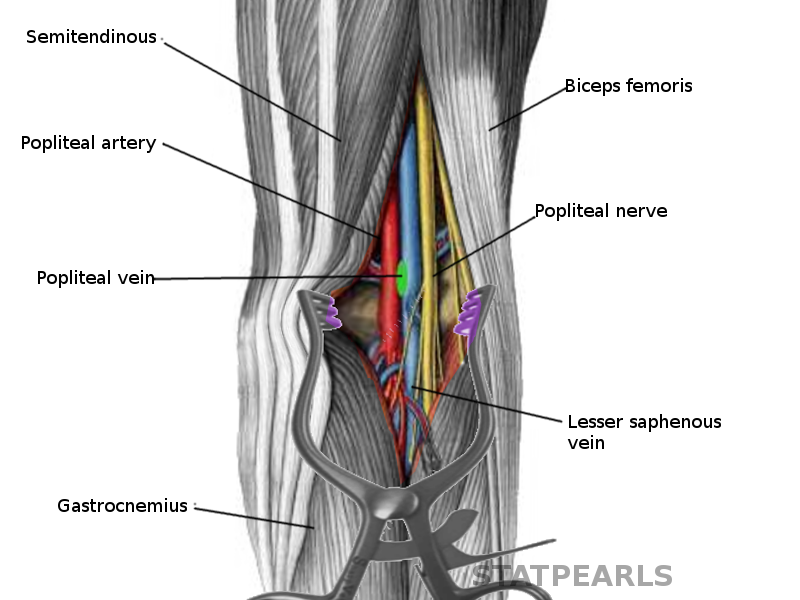

The popliteal vein is found within the popliteal fossa. The popliteal fossa is defined by the biceps femoris proximolaterally; the semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles proximomedially; and gastrocnemius distally. The tibial nerve, popliteal vein, and popliteal artery are all found within the fossa. The structures present from medial to laterally in the following order: popliteal artery, popliteal vein, and tibial nerve. After leaving the popliteal fossa, the vein passes through the adductor hiatus which is found in the adductor magnus muscle and is renamed to the femoral vein.

The superficial compartment of the thigh contains the subcutaneous tissues between the skin and muscle fascia while the deep compartment includes the tissues deep to the muscular fascia. The superficial compartment contains superficial and perforating veins. The deep compartment contains the deep veins. The communication between the compartments occurs with perforating veins. [2]

Embryology

The lower extremity limb bud development begins in the fourth week of development and continues into the fifth week.[1] The angiogenesis of the lower leg’s venous system is thought to be induced by angio-guiding nerves laying out the framework for the venous plexuses that that go on to form the veins of the lower leg. Several venous plexuses merge at the popliteal region of the leg which results in several different configurations of the roots of the popliteal vein.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The popliteal artery runs anterior to the popliteal vein and is the primary blood supply to the popliteal region as well as the lower leg. It is a continuation of the femoral artery that is referred to as the popliteal artery once it passes through the adductor hiatus. At the level of the popliteal muscle, it sends a branch anteriorly to form the anterior tibial artery, and the popliteal artery continues to split into the posterior tibial artery and the peroneal artery. Within the popliteal fossa, the vein crosses the artery moving from the medial aspect to the lateral aspect. [4]]

The lymph from the lymph nodes in the popliteal fossa ascends within the thigh along with the popliteal vessels and then subsequently the femoral vessels until it drains into the deep inguinal lymph nodes. There are several lymph nodes embedded in the fat layer found in the popliteal fossa and along the popliteal vessels.[5]

Nerves

The location of the popliteal vein is medial to the tibial and common peroneal nerves in the popliteal fossa.

The sympathetic nervous system is essential in the control of venous capacitance and is responsible for the baroreceptor reflex in which the venous return to the heart increases via a reflex increase in sympathetic tone in response to hypotension.[6]

Muscles

Muscle contraction of the lower limb is important in maintaining adequate venous blood flow to the heart. Contraction of calf muscles, like the gastrocnemius and soleus, cause an increase in pressure in veins of the lower leg such as the posterior tibial vein. This increased pressure creates a gradient by which the blood can move proximally into the popliteal vein and back towards the heart.[7]

Physiologic Variants

There are several different anatomic variants of the origin of the popliteal vein. Typically the vein originates at the level of the popliteal muscle from the confluence of the anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal veins. However, documented variants include popliteal veins that originate more proximal near the adductor hiatus from either two or three of the contributing tributaries. Additionally, there have also been cases reported of duplicate popliteal veins.[2]

Variations also exist in the vein’s anatomical relationship with its arterial counterpart. The popliteal vein is typically posterolateral to the popliteal artery, though anatomists have noted variations in which the vein crosses the artery and lies medial to it. Additionally, there have been cases reported in which there were no popliteal nor femoral veins but rather a persistent sciatic vein draining the lower extremity in their place.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Because of its location in the popliteal region of the knee, it is crucial to know the location of the popliteal vein in a posterior approach to the knee. The posterior approach to the knee is not a common technique, and its most common utility is in the repair of the neurovascular bundle in trauma cases. Though less common, it also has utility in the repair of avulsion fractures from the posterior cruciate ligament attachment on the tibial plateau, Baker cyst excision, gastrocnemius muscle recession secondary to contractures, and hamstring lengthening.[9]

It is essential to have a complete understanding of the normal anatomy as well as the anatomical variants of the popliteal vein and the rest of the neurovascular bundle in the popliteal fossa as an injury to these structures could result in significant neurovascular compromise to the lower extremity. When performing deep dissection using the posterior approach, blunt dissection is suggested near the neurovascular bundle to minimize the risk of injury.[9]

In traumatic popliteal injuries, the popliteal artery and vein are both at risk. Though an injury to the popliteal artery carries an increased risk of lower leg ischemia and subsequent amputation, cases in which both the popliteal vein and artery are compromised carry have not been found to increase the rates of amputation versus arterial injury alone.[10]

Clinical Significance

The popliteal vein is one of the most common locations for the development of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). These can be life-threatening when a portion of a thrombus to breaks off and forms a pulmonary embolus as it travels to the lungs. Also, whenever there is cryptogenic stroke always perform the duplex ultrasound of the legs to rule out deep vein thrombosis. If present, one should perform the transesophageal echocardiography to rule out patent foramen ovale. Patients who have deep vein thrombosis need to start on coumadin or newer anticoagulation agents. The duration of the treatment depends on the provocating factor involved. Common risk factors of DVT include smoking, reduced mobility, recent surgery, and combined oral contraceptive pills.

Superficial venous thrombosis (SVT) is also reported with gaining incidence due to increased recognition and diagnosis. The common predisposing factors are similar to DVT and include varicose veins, immobilization, trauma, obesity, and the use of oral contraceptives. An SVT can occur in tributaries of the popliteal vein including the small saphenous vein. [11]

Popliteal vein entrapment is an uncommon development that typically occurs secondary to a muscular or tendinous anomaly causing compression of the vein. The most common cause is an anatomic variation in the location of the heads of the gastrocnemius muscle. Other causes of entrapment may include popliteal artery aneurysms, hypertrophied gastrocnemius muscles in athletes, and ruptured popliteal cysts. Popliteal vein entrapment can cause similar symptoms to that one might see in chronic venous insufficiency. Some of these sequelae include lower leg edema distal to the entrapment, venous claudication, venous varicosities in the lower extremities, skin stasis changes, and DVT development secondary to venous stasis.[12]

Other Issues

Popliteal vein aneurysms, while uncommon, are another dangerous development in the vessel as they can increase clot formation risk and subsequent pulmonary embolism causing significant morbidity and mortality.[13]