Continuing Education Activity

The SMAS (superficial musculoaponeurotic system) plication face lifting technique evolved to provide an effective means of suspending the soft tissues of the face beyond simply tightening the skin. Developed by Swedish plastic surgeon Tord Skoog in the 1970s, it has become increasingly popular as a facial rejuvenation option. Several variations of the technique have been described. Plication is the folding of the SMAS with subsequent suturing to apply tension; imbrication is the removal of a segment of SMAS with overlapping of the cut edges and closure of the defect serving to resuspend the tissue. SMAS flap facelift techniques are generally performed as outpatient procedures and are easily taught to trainees. This activity reviews the SMAS plication facelift procedure, its indications, and contraindications and highlights the interprofessional team's role in patient selection and management.

Objectives:

Identify the technique of the SMAS plication facelift.

Assess the indications for SMAS plication facelifting.

Evaluate the complications of SMAS plication facelifting.

Communicate the importance of improving care coordination within the interprofessional team to enhance care delivery for patients undergoing SMAS plication facelifting.

Introduction

Facial rejuvenation techniques have increased in number and complexity over the past several decades, with demand for these procedures steadily increasing since the early twentieth century. Since 2016, rhytidectomy (facelift) has been in the top 5 most commonly performed cosmetic surgical procedures in the United States, along with breast augmentation, blepharoplasty, liposuction, and rhinoplasty. Patients request facelifting because, with advancing age, loss of collagen decreases skin turgor, and chronic sunlight exposure contributes to decreased skin elasticity. In the third to fourth decades of life, soft tissue brow descent begins, with buccal fat pad descent and atrophy, as well as resorption of facial bone occurring in the sixth to seventh decades of life and beyond.[1][2] For this reason, the most common patient demographic for elective facelift procedures is females ranging in age from thirties to late seventies.

Patients desiring improvement in skin smoothness and jaw contour and those with unilateral flaccid facial palsy may benefit from facelifting. For less invasive rhytidectomy techniques, such as superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) plication approaches, ideal patients are thin and possess mild to moderate skin laxity and jowling without major ptosis of the malar fat pads or deep nasolabial folds (see Image. Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System Plication Procedure). Thicker-skinned and overweight patients tend to have less than optimal clinical outcomes with these more conservative procedures.[3] SMAS plication facelifting aims to improve facial appearance by sharpening the cervicomandibular angle, reducing the jowls, and improving the jawline's definition.

The SMAS plication facelifting technique evolved to provide an effective means of suspending the soft tissues of the face beyond simply tightening the skin. Developed by Swedish plastic surgeon Tord Skoog in the 1970s, it has become increasingly popular as a facial rejuvenation option.[4] Several variations of the technique have been reported to provide resuspension of the SMAS in a favorable vector. Some surgeons elevate SMAS flaps and transpose them; some prefer plication and some imbrication. Plication is the folding of the SMAS with subsequent suturing to apply tension; imbrication is the removal of a segment of SMAS with overlapping of the cut edges and closure of the defect serving to resuspend the tissue. SMAS flap facelift techniques are generally performed as outpatient procedures and are easily taught to trainees. While all operations risk the development of complications, rates of adverse events occurring in SMAS facelifts are low, and patient satisfaction is generally high.[5]

Anatomy and Physiology

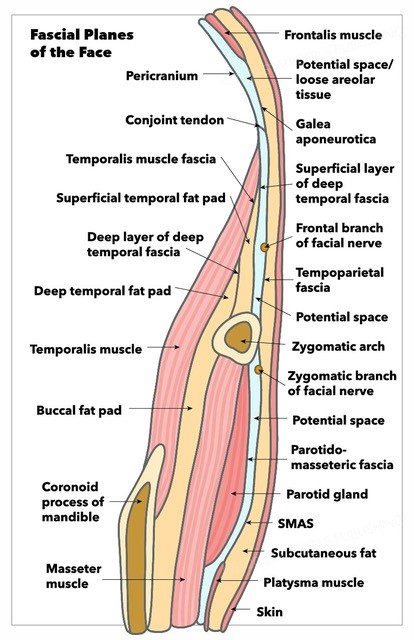

The critical conceptual foundation for facial anatomy is tissue planes; understanding the relationships among fascial planes within the face permits the surgeon to operate effectively while minimizing the risk of complications (see Image. Fascial Planes of the Face). Perfusion of the facial skin is supplied by the subdermal vascular plexus, under which is a fatty layer of subcutaneous tissue. Beneath the subcutaneous tissue lies the SMAS layer.[6]

The SMAS sits just superficial to the parotidomasseteric fascia; anteriorly, the SMAS is contiguous with the mimetic muscles, and inferiorly, the SMAS merges with the platysma superior to the body of the mandible. Superiorly, the SMAS adheres to the periosteum of the zygomatic arch but is contiguous above that of the temporoparietal fascia (TPF). The TPF, in turn, adheres to the skull's temporal bone at the conjoint tendon, located along the temporal line at the superior edge of the temporalis muscle. Superior to that, the TPF becomes the galea aponeurotica and the frontalis muscle. Although this plane adheres to bone at the zygomatic arch and the temporal line where the fascial layers condense, it is important to regard it as a single fascial structure to remain cognizant of the location of facial nerve branches. As a general rule, facial nerve branches run deep to this layer.

The facial nerve lies deep to the SMAS while it courses through the parotid gland and then remains deep to the SMAS, running along the fascia of the masseter muscle, where it can be encountered during more aggressive facelifting techniques, such as deep plane rhytidectomy. Facial nerve branches then innervate the mimetic muscles from their deep surfaces, except for the levator anguli oris, mentalis, and buccinator muscles, which are innervated from their superficial surfaces because of their deeper location within the face.

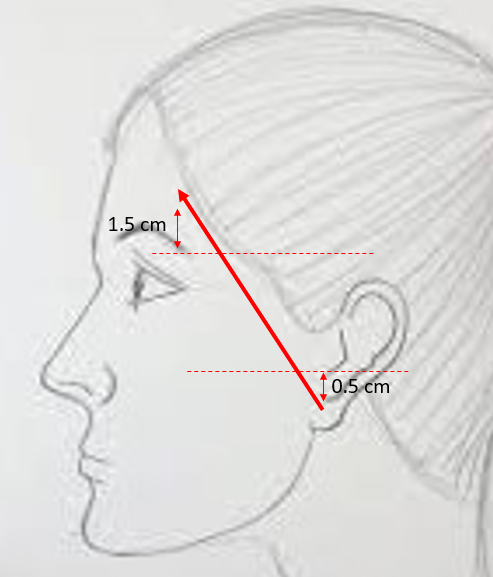

The facial nerve is commonly thought of as possessing 5 main extratemporal branches separate from the main nerve trunk at the pes anserinus, located within the parotid gland. The most superior branch, the frontal branch, runs along the deep surface of the TPF on its way to innervate the frontalis and corrugator supercilii muscles, with a course approximated by a line between a point 5 mm below the tragus and a point 15 mm above the lateral brow (see Image. Course of the Temporal Branch).[7] The inferior division, comprised of the marginal mandibular and cervical branches, runs deep to the platysma muscle, with the marginal mandibular nerve primarily innervating the depressor anguli oris and mentalis muscles and the cervical branch controlling the depressor labii inferioris and the platysma.

The zygomatic and buccal branches of the facial nerve innervate the midfacial muscles and run in the same plane with the parotid duct and transverse facial vessels. The zygomatic branch is primarily responsible for eye closure via the orbicularis oculi muscle, and the buccal branch controls most of the midface muscles. The buccal branch most responsible for controlling the smile is located at Zuker's point, roughly halfway along a line between the root of the helix and the oral commissure.[8] In a similar anatomical arrangement, the greater auricular nerve and external jugular vein, both of which are at risk of injury during face lifting, lie beneath the platysma and superficial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, with the nerve running roughly 1 cm posterior to the vein. See Image. The great auricular nerve (GAN) crosses over the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM).

Veins frequently run close to nerves, and the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve frequently wraps around the facial vein, which lies just posterior to the facial artery. In most patients, the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve courses superior to the inferior margin of the mandible anterior to the gonial notch, but there is increasing evidence that injury to the cervical branch of the facial nerve is commonly responsible for postoperative lower lip asymmetry.[9] The cervical branch can be located ~1 cm inferior to the halfway point of a line between the mentum and the mastoid process.[10]

Beyond the neurovascular anatomy, it is important to understand how soft tissue attachments to the underlying bone affect facial aging and, therefore, surgical correction of the aging face. With respect to SMAS plication face lifting, the mandibular retaining ligaments are most significant, as they are located at the pre-jowl sulci and are responsible for causing the formation of jowls due to the way that they tether the skin to the bone.[11] Dividing these ligaments intraoperatively allows the surgeon to refine the jaw contour with a more effective reduction of the jowls. Similarly, attachment of the skin to the muscle with minimal intervening subdermal fat causes the appearance of the nasolabial folds (NLFs), which form boundaries beyond which the malar fat pads cannot droop even when the malar retaining ligaments (McGregor's patch) loosen over time. The NLFs are not divided intraoperatively but can be effaced by elevating the malar fat pad from the underlying zygomaticus muscles with resuspension to a more youthful, superolateral position; this procedure, known as a midface lift, often comprises part of a deep plane rhytidectomy.[12]

Indications

Indications for SMAS plication facelift include:

- Skin and soft tissue laxity of the lower face

- Jowling

- Facial asymmetry due to chronic flaccid facial paralysis

- Plastysmal banding, if concurrent neck lift or platysmaplasty is planned

- Reasonable expectations for outcomes

Contraindications

Contraindications for SMAS plication facelift include:

- Inability to set reasonable outcome expectations

- Psychiatric dysfunction

- Significant ptosis of the malar fat fads with deep nasolabial folds

- Significant adiposis of the facial soft tissues

- Weight instability

- Active smoking

- Collagen vascular diseases or other wound-healing anomalies

- Uncontrolled diabetes

- Uncontrolled hypothyroidism

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Bleeding diathesis or inability to discontinue anticoagulants perioperatively

- Malnutrition

- Poor cardiopulmonary reserve

Equipment

Equipment necessary to perform SMAS plication facelift includes:

- Facelift scissors: Gorney-Freeman, Kaye, Goldman-Fox, Castañares, or similar

- Suture scissors: Mayo, iris, or tenotomy

- Retractors: Freeman rake, Joseph double prong skin hooks, Ferreira facelift retractor

- Forceps: Adson-Brown, 0.5 mm Castroviejo

- Needle drivers: Halsey or Webster, Castroviejo

- Scalpel: multiple #15 blades, #3 Bard-Parker handle

- Electrocautery: bipolar and monopolar

- Sutures: 2-0 quill suture, braided polyester or polydioxanone, 4-0 polyglactin, 5-0 nylon, and polypropylene

- Skin stapler

- Skin marker

- Hypodermic needle and syringe for injection of local anesthetic or tumescent solution

- Dressing supplies

Personnel

Personnel required to perform a SMAS plication facelift include:

- Surgeon

- First assist, if necessary

- Scrub tech

- Circulating nurse

- Anesthesia provider, if necessary

Preparation

The patient is placed supine on the operating table, and general anesthesia or sedation may be induced if desired. While orotracheal intubation is most common for general anesthesia, many surgeons prefer nasotracheal intubation to improve surgical access to the neck and perioral region. In either case, securing the endotracheal tube with a 2-0 silk suture may help prevent inadvertent extubation with intraoperative manipulation of the head and neck. Local anesthetic or tumescent solution is injected, and a surgical prep is performed with 10% povidone-iodine or 70% isopropyl alcohol, depending on the surgeon's preference. If concomitant blepharoplasty is planned, the periocular scrub should be 5% povidone-iodine; otherwise, the eyes may be protected from the scrub with sterile adhesive film dressings to prevent corneal injury.[13][14]

Technique or Treatment

The surgical procedure begins with a tumescent solution or local anesthetic infiltration into the subcutaneous plane. Tumescent anesthesia involves introducing a large volume of dilute local anesthetic combined with normal saline, sodium bicarbonate, and epinephrine into the subdermal plane, producing temporary firmness in the target area.[15] Typically, a mixture of 0.05% or 0.1% lidocaine, normal saline, and 1:100,000 epinephrine is used. Using a #15 blade, the incision begins in the temporal area, runs anterior to the ear, and then into the post-auricular sulcus. A portion of the incision may be hidden just medial to the free margin of the tragus if the patient is female, but the incision is typically made within a preauricular rhytid for male patients to avoid pulling hair-bearing skin onto the tragus during closure. If necessary, the incision can be extended to provide sufficient subcutaneous dissection for an acceptable vector of SMAS traction based on the individual patient's needs. Hydrodissection with the tumescent solution may be used to develop the subcutaneous tissue plane, facilitating flap elevation.

The flap is then undermined and elevated with scissors, using either a snipping or a spreading technique. The SMAS layer is identified as the fibrovascular layer deep to the subdermal fat and superficial to the parotid fascia. Anteriorly, the SMAS is thicker near the ear, and it thins as it spreads along the cheek. SMAS plication to achieve the desired lift is then performed using a 2-0 or 3-0 permanent or long-lasting dissolvable suture, such as polyester or polydioxanone, respectively. Excess SMAS in the infra-auricular area is excised. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve when working in the lower face and upper neck.

Hemostasis should be meticulous to avoid hematoma formation, which is most likely to occur in the first 24 postoperative hours. Closure of the wound involves suspending the skin in an appropriate superolateral vector and excising the excess to avoid placing too much tension across the wound. The closure is accomplished with sutures on the skin and staples in the hair-bearing scalp or with sutures throughout. Patients are instructed to sleep upright for the first week to minimize edema and are given a neck support dressing for 1 to 2 weeks. The neck can remain tight for up to 3 weeks. Sutures are removed on postoperative day 7, and patients are seen at 3 and 6 weeks for follow-up. Depending on physician preference, medication is prescribed for pain control for at least the first week postoperatively.[14]

An important variation of the SMAS plication technique is the minimally-invasive cranial suspension facelift described by Tonnard et al in 2007.[16] This approach utilizes a short incision confined to the preauricular region and the temporal hair tuft, through which 3 purse-string sutures are placed that elevate the jowls, the central cheeks, and the malar fat. The technique thus similarly addresses the jawline and face to a classic SMAS plication rhytidectomy but also provides a midface lift.[17] Theminimally-invasive cranial suspension rhytidectomy can also be combined with a necklift to address a broader range of facial aging concerns.[18]

Because rhytidectomy typically rejuvenates patients by approximately 10 years, some patients return for repeat procedures. While most revision surgery can be more challenging than primary operations, a unique feature of rhytidectomy is that flap elevation in the original surgery causes a delayed phenomenon in which the vascularity of the facial skin is improved, and the thin scar plane that remains in the subdermal region after the original surgery is easily divided and facilitates subsequent re-elevation of the skin. The primary challenge with revision rhytidectomy is incision placement because each surgeon has a unique preference for incision planning, and operating through a different surgeon's incisional scar may be inconvenient if the same surgeon is not performing the revision operation.

Complications

The most common complications of an SMAS plication include hematoma, earlobe anesthesia/hypesthesia due to greater auricular nerve injury, lower lip asymmetry, delayed wound healing, scar hypertrophy, areas of transient alopecia in the incision, surface irregularities that may require fat transfer, skin flap necrosis, infection, and inferior malposition of the earlobe (pixie ear deformity).[19] Hematomas are more common in men than women because of the greater blood supply to the facial and cervical skin required to support hair follicles. Hematomas are also more likely to occur in patients with uncontrolled hypertension or taking anticoagulants. Small hematomas may be managed in the office with aspiration and pressure dressing, but larger ones require a return to the operating room for definitive hemostasis.

Motor nerve dysfunction may be permanent but is much more commonly transient and is most likely to result in lower lip asymmetry or brow ptosis (see Image. Rhytidectomy, Complications).[20] Patients may also experience ecchymosis and edema, which should abate by day 14 but may persist for up to 6 weeks. Pain and tenderness are expected postoperatively, and many patients also note some facial hypesthesia for several weeks after surgery. It is important to realize that over 50% of patients experience some psychological dysfunction, primarily transient depression, which must be recognized and managed.[21] Most patients benefit from reassurance, but some may require short-term pharmacological therapy.

Clinical Significance

This technique differs from more invasive facelifting techniques in that it does not typically place the facial nerve branches at risk due to conservative flap elevation, but it is very effective for reducing the appearance of jowls and restoring a youthful jawline. Because of its limited dissection, it does not address midfacial soft tissue ptosis and may have a shorter duration of postoperative edema. SMAS plication facelifting is comparatively simple to perform - and teach - and can be offered to patients as an outpatient procedure. Provided appropriate patient selection, satisfaction rates are high. Patients with thicker skin, midfacial ptosis, or deep nasolabial folds are poor candidates for this operation and may benefit from a more aggressive facelift approach instead. There are numerous ways of performing an SMAS plication facelift based on surgeon preference and patient requirements. The SMAS plication is only 1 of many different rhytidectomy techniques that may be employed to reduce the appearance of facial aging.[12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Rhytidectomies, even less invasive varieties such as SMAS plication facelifts, are among the more extensive cosmetic procedures performed within the head and neck and require a skilled team to ensure successful outcomes. The operating surgeon must carefully evaluate individual patients' candidacy preoperatively and counsel them to generate reasonable expectations that maximize patient and surgeon satisfaction with the procedure's results. Some patients may not be suitable surgical candidates, and other non-invasive procedures, such as skin resurfacing or injectable treatments, may be more appropriate. A thorough discussion of the complication risks before surgery is essential. Ensuring patients have access to nurses throughout the perioperative period to answer questions and provide guidance regarding self-care enhances the recovery process. A medical photographer for pre and postoperative photo documentation is also important, and many patients benefit from visiting an aesthetician after recovery is complete. While most facelift complications are uncommon and not life-threatening, an interprofessional operating room team experienced in rhytidectomy facilitates the procedures and minimizes complications.